Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

The Pig War

Although the islands (located midway between Bellingham, Washington and Victoria, British Columbia) were of questionable economic value, national pride and a dubious belief in their strategic military importance nearly led to war in 1859.

The border between British territory and the United States through the Strait of Juan de Fuca should have been firmly established in the Oregon Boundary Treaty of 1846. According to the agreement, the border, after splitting the mountains along the forty-ninth parallel, would continue west, south, and west again, through “the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver’s island.”

This vague and noncommittal definition suited admirably at the time, because no one suspected that the islands lay astride the ill-defined border, and in any case, no one lived on them.

But twelve years later, in 1858, gold was discovered along the Fraser River, and military convention dictated that the westernmost island, San Juan, was strategically important as the guardian of the waterway leading to Puget Sound and the gold-laden sand bars along the Fraser.

One British official, Captain James C. Prevost, warned that the loss of San Juan might “prove fatal to Her Majesty’s possessions in this quarter of the globe.” Not surprisingly, all the islands, valuable or not, were promptly claimed by both sides.

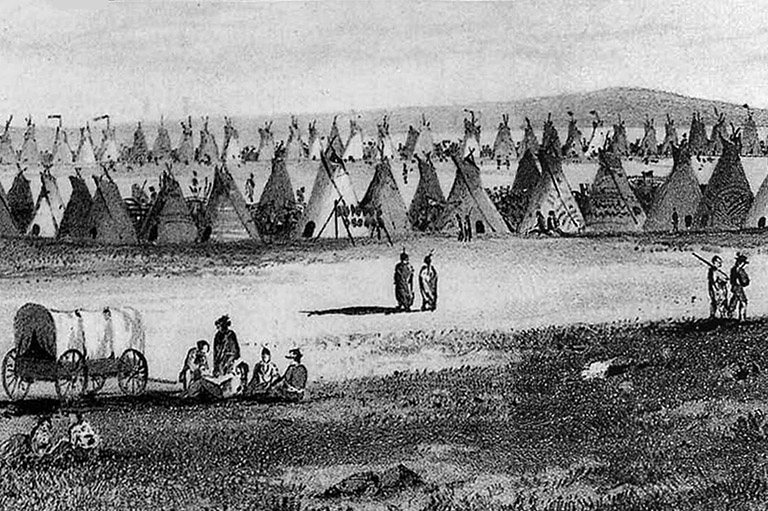

On San Juan, the shepherds on a Hudson’s Bay Company sheep farm and a small congregation of American farmers had been eyeing each other suspiciously since about 1855, when an enterprising American agent sought vainly to collect U.S. taxes from the company and seized thirty-four breeding rams instead.

The Joint Boundary Commission of 1856 failed to reach a consensus on the location of the border, but the negotiators did agree to avoid further conflict until the matter was resolved diplomatically.

And there matters would have rested, awaiting the attentions of American and British statesmen, but for the whimsical wanderings, on a fine day in June 1859, of a delinquent British-Canadian pig.

The pig, recognizing no boundaries, stumbled across the island, trampling and feasting in the garden of an American settler. Outraged, the settler immediately shot the beast (and presumably ate it). The indignant company agent demanded immediate restitution for the swindled swine, to no avail.

Somehow the affair escalated, and General William S. Harney, commander of the U.S. army in the Pacific Northwest, a man with a reputation for brash undertakings, dispatched sixty soldiers under the command of Captain G.E. Pickett to occupy the island and put an end to British whining.

Harney refused to remove his troops even when British navy ships patrolled off-coast.

The patriotic outcry in nervous Fort Victoria was predictable, especially in light of the sudden influx of American gold-seekers to the Fraser the year before.

“We must defend ourselves,” bellowed J.S. Helmcken, speaker of the legislative assembly, “for the position we occupy today would make the iron monument of Wellington weep, and the stony statue of Nelson bend his brow!”

Thankfully, nothing so desperate was necessary, because after a few months of delicate negotiation Washington quietly removed the belligerent Harney and most of the American troops, and the two countries agreed to jointly occupy the island until the boundary could be amicably settled.

The joint occupancy agreement, with detachments of soldiers encamped at opposite ends of the island, lingered for over a decade, until after the Civil War when the matter was submitted to the German Kaiser Wilhelm for arbitration. In 1872, the Kaiser awarded all the San Juan Islands to the United States, ending the Pig War — and finally settling the boundary between Washington and the new Canadian province of British Columbia.

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!