We Stand on Guard

Quebec City, June 24, 1880

“Bravo! Bravo!” The elegantly dressed men and women didn’t want to stop clapping. It was as if they knew that the song they had just heard, “Chant National,” was something very special.

“They love it!” Adolphe-Basile Routhier whispered to the man sitting next to him. “Your music, Calixa — it is perfect! It was so inspiring that it took me no time at all to write the words.”

Calixa Lavallée tried to be calm, but a huge smile broke out on his face. “Your poetry is the perfect match. I know the crowd will agree tomorrow when they hear the choir sing the words. I do believe our effort to write a national hymn for French Canada is a success! Even the governor general is impressed.”

Ernest Gagnon pushed his way through the crowd to congratulate his friends. “I can’t believe anyone could have come up with anything better than your ‘Chant National.’ And to think it all started with a letter from that priest in Trois-Rivières, suggesting we have a national anthem for this year’s Saint-Jean-Baptiste celebrations.

“I know Father Caron thought we should have a competition, but there just wasn’t time. And besides, this worked much better,” Gagnon continued. “I’m not sorry we had you write this song. It’s wonderful!”

“The English have ‘God Save the Queen’ and ‘The Maple Leaf Forever,’” said Routhier, “but there is no place for us French Canadians in their songs.”

Lavallée nodded. “I don’t mean to sound immodest, my friends, but it feels good to think that we have an anthem that’s truly ours.”

Montreal, November 25, 1908

Stanley Weir gazed at the printed sheet of music in his hands, an astonished grin on his face. “I can’t quite believe it, Gertie. ‘O Canada,’ with my name on it!”

His wife shook her head. “I know you’re a lawyer, but you’re also a great poet. Your words are beautiful. Much nicer than those other translations.”

“Don’t be too hard on them, Gertie. It’s not easy to come up with patriotic words that are also poetic,” Weir replied. “This was just my way of helping celebrate Quebec City’s 300th anniversary.”

“You’re much too kind, Stanley. The other versions were awful and you know it. That’s why they never caught on. Nobody wants to sing things like ‘No stains thy glorious annals gloss,’ or ‘From pole to borderland.’ That’s not poetry at all. And besides, most of them talk too much about the Empire and Britain — the whole point of ‘O Canada’ was to have an anthem that included both French and English.”

“Besides,” said Gertie, “It feels good to think that we have an anthem that’s truly ours.”

New Words, Old Words

Stanley Weir’s English-language poem included the lines “True patriot love, Thou dost in us command.” Nobody’s quite sure why the second part was changed to “In all our sons command” around the time of the First World War. It might have had something to do with women’s fight for the right to vote.

As early as 1980, representatives in Parliament started trying to change the English words of the anthem so they included people of all genders. On January 31, 2018, the official words of “O Canada!” finally became more like the original version: “True patriot love in all of us command.”

Although the English words have changed slightly a few times, the French words have always stayed the same. Many people sing a bilingual version that goes back and forth between the two languages.

Others have suggested we should remove references to “native land” since many Canadians weren’t born here, or that we should honour First Nations people by changing the words to “Our home on native land.” What do you think?

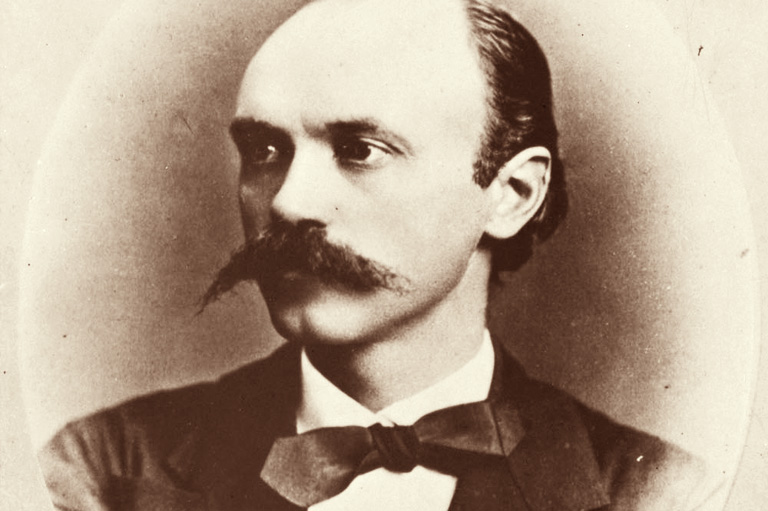

Calixa Lavallée wrote the music for our national anthem in 1880; Adolphe-Basile Routhier wrote the words in a single evening after hearing Lavallée’s composition.

Under the title “Chant National” it was a hit right away in French Canada, but didn’t catch on among English Canadians until after 1901 when it was first sung publicly in English. (Many music experts say the opening notes sound an awful lot like a piece from the Mozart opera The Magic Flute.)

There were at least four English-language versions of “O Canada,” ranging from a straight translation of Routhier’s words to a variety of poems to suit Lavallée’s music. If you read them online, you’ll see why they were passed over!

By the First World War, Weir’s English words had caught on and “O Canada” was gradually being accepted as our national song. By the late 1920s, children were singing it in school and you’d hear it at most public events.

There were dozens of attempts to make it our anthem, but finally, on June 27, 1980, the government made it official. On July 1, 1980, Governor General Ed Schreyer had descendants of both Routhier and Weir beside him when a public ceremony made “O Canada” our official national anthem.

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive features both English and French versions of Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids.

Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids — 3 digital issues per year for as low as $13.99. Tariff-exempt!