Taking to the Streets

On the corner of Lily Street and Market Avenue in Winnipeg’s historic Exchange District, a weathered steel monument commemorates the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike. The 1919 Marquee — a Monument to the Winnipeg General Strike includes a map of key strike locations as well as a brief overview of the significance of some of the sites.

As I begin my zigzag route through the Exchange District, I reflect on the strike’s beginning on May 15, 1919, when unionized workers assembled in front of city hall and marched south to the corner of Portage Avenue and Main Street. Within two hours, thousands of non-unionized workers joined them. Shops, factories, and restaurants closed.

On Main Street in front of the civic centre buildings that have replaced the “gingerbread” Victorian city hall, I visualize 1919 traffic — a cacophony of clattering trolleys, motor vehicles, and horseshoe clops — disrupted by marching strikers, and I imagine the eerie quiet that descended a few hours later after streetcars and delivery vehicles stopped service.

Weeks into the strike, on Saturday, June 21, the street in front of city hall was again the scene of a pivotal event: Thousands marched to protest the arrest of strike leaders.

By this time, streetcars were running again, and angry protesters overturned one streetcar and set it on fire. Fatal violence ensued when the members of the North West Mounted Police, armed with baseball bats and firearms, rode into the crowd. One striker died instantly after being hit, and another wounded striker died the following day. Thirty others were injured, and dozens were arrested.

Fighting spilled into a side street that became known as Hell’s Alley. A ten minute conflict resulted in twenty-seven casualties. The Centennial Concert Hall now occupies the space, but I can still imagine the terror of being trapped in a narrow lane as I walk a block east on Elgin Avenue, where railway tracks remain, now embedded in the street, and faded numbers on brick warehouses identify former loading docks.

A public art piece, the tilted and half-sunken Bloody Saturday, to be unveiled in the summer of 2019 on the corner of Main and Market, will be a visible reminder of the day’s events. The James Street Labor Temple, at the time located a couple of blocks away, no longer exists.

Home to the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council, the central organization of unionized workers, it was Central Strike Committee headquarters. The Central Strike Committee held rallies a block away in Victoria Park, where Waterfront Drive now runs. A condominium apartment block sits on one side, and the colourful, trendy Mere Hotel is on the other. Nearby, in Stephen Juba Park along the tree-lined banks of the Red River, I picture crowds of gathered workers.

The strike feels more remote at the next two still-standing landmarks, the Thomas Scott Memorial Orange Hall, where local unions rented space, and the Walker Theatre, now the Burton Cummings Theatre, where a December 1918 political and labour meeting attracted over 1,700 people.

The strike becomes real again at the Telegram Building, a four-storey brick edifice with ornate detailing. After being shut down for about a week at the beginning of the strike, the Winnipeg Telegram, the Manitoba Free Press, and the Winnipeg Evening Tribune reported with definite anti-strike biases.

The Citizens’ Committee paid for fullpage ads with headlines like “Don’t Be Misled — the Only Issue is Bolshevism.” The Winnipeg Citizen, published daily by the Citizens’ Committee, voiced similar sentiments. At the same time, the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council’s Western Labor News published a daily pro-strike bulletin. Newspaper boys no longer peddle papers on the section of McDermot Avenue once known as “Newspaper Row,” but the rhetoric and division of opinion seems familiar and current.

Other sites of historical significance exist beyond the boundaries of the monument map. A “Permitted by Authority of the Strike Committee” sign in a Winnipeg Police Museum exhibit makes me realize how the strike disrupted daily lives.

These signs were issued to restaurants, movie theatres, and milk, bread, and ice deliverers so they could continue to provide services. “Special Police” badges and armbands in the display case evoke feelings of uncertainty and fear of anarchy that must have been prevalent during the strike.

The city’s entire police force was dismissed on June 9 for refusing to sign an agreement prohibiting membership in any union. The city then hired hundreds of special recruits. A strike exhibit at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights contains similar artifacts.

The 1919 Winnipeg General Strike is now credited with laying the seeds of the modern Canadian labour movement.

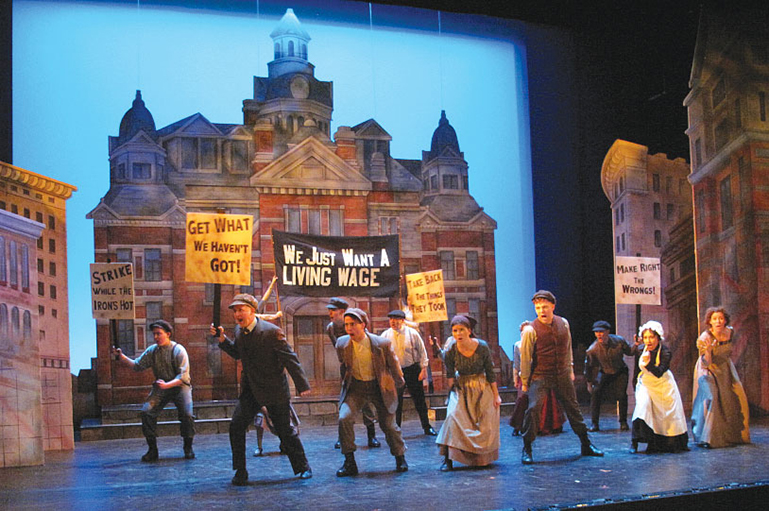

Its memory is particularly fresh on its hundredth anniversary, with a series of community events sponsored by the Manitoba Federation of Labour. The 2019 season of Rainbow Stage, Canada’s largest and longest-running outdoor theatre, presents Danny Schur’s Strike! The Musical. A movie version is slated for release (see trailer below). Winnipeg’s Exchange District BIZ will offer a special version of its general strike walking tour.

As I view sites that might be on that tour, I wonder how 1919 Winnipeg residents would feel about the strike’s legacy.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement