Wreck and Rescue

It was a few hours before dawn on April 1, 1873, when Michael Clancy awoke to a loud hissing sound. The sixty-four-year-old fisherman, who lived with his family on tiny Meagher’s Island, Nova Scotia, peered through the window and saw clouds of steam drifting eerily from the south side of the island. From out of the clouds something shot into the sky and exploded with a loud bang and a bright flash. Then another one went up and exploded.

The house was in an uproar. It was a small abode — the only dwelling on Meagher’s Island — and it held a large family: Besides Clancy and his bedridden wife, Jane, there were his twenty-eight-year-old daughter, Sarah Jane O’Reilly, with her two young children, Mary and James; a second daughter, Elizabeth; his sons, Michael and James; and his brother, Edmund, with his son, Alex. There was also a boy named Eddie Mullins, probably another relative — eleven people all told, along with the dog who, at the moment, was very spooked by the distress rockets exploding overhead. With his brother Edmund and teenage son Michael, Clancy headed towards the source of the commotion. As they walked, a wraithlike apparition emerged from the mist. The dim glow of their lantern revealed a sopping, staggering, freezing man, more dead than alive. Robert Thomas had just swum ashore from a grounded ship, a super-human effort in the icy, churning waters.

They directed him back to the house and kept going towards the south side of the island, which lay exposed to the open Atlantic Ocean. Soon they beheld the biggest ship they had ever seen, half sunk, about twenty-five metres offshore, getting walloped by huge waves. Steam from the boilers swirled around the ship, although the hissing sound that awakened Clancy had stopped — the ship’s engineers had released the pressure on the boilers, fearing that they might explode when the cold sea water struck them.

A few people languished on the rocky shore of Meagher’s Island, too exhausted to stand, having somehow saved themselves from the sinking vessel. Bodies were everywhere in the water and along the shore. Some men were standing on a large, flat, offshore rock between the ship and the island. Others were in the water, trying to pull themselves on a rope strung from the ship to the offshore rock; but the near-freezing water was overwhelming, and most were dropping off and drowning. Still others clung to the ship’s rigging, exposed to the cold wind as the temperature hovered near zero, while some hung on to the side of the partially overturned hull. “There were no screams of women; no yelling men,” passenger Samuel Vick later told reporters. “Every one stood still and was silent. Those who died made no noise except as their bodies fell to the deck.”

Clancy was witnessing the demise of the White Star Line steamship Atlantic, the largest maritime disaster to that point in Canadian history.

Article continues below...

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

On March 20, 1873, the SS Atlantic— a 128-metre, steam-and-sail-powered ship — had left Liverpool, England, for her nineteenth crossing to New York. The ship had stopped briefly at Queenstown, Ireland, to take on passengers, then continued on her journey with just under a thousand people aboard. Almost all of the passengers were immigrants, with only thirty-five travelling in saloon class, as first class was called at that time.

She fought rough seas and gales much of the way across the Atlantic Ocean, consuming coal at an alarming rate. Off Nova Scotia, the chief engineer, John Foxley, gave Captain James Williams the distressing news that they were low on coal. Making New York was not a sure thing. After conferring with his officers, the captain decided to put in to Halifax, which was 270 kilometres off his starboard beam. At 1:00 p.m. on March 31, he ordered a right turn, and they proceeded towards Halifax, fourteen hours away. They would be approaching the big harbour in the dark.

But somehow the Atlantic missed Halifax, and shortly after 3:00 a.m. she slammed into a large, flat rock off Meagher’s Island. The bow rode up onto the rock, and the ship came to a jarring halt, throwing people from their beds and extinguishing all the lights aboard. Water poured up through the damaged bottom, and she started to sink by the stern — five, ten, fifteen metres — until the rudder came to rest on the granite rocks below. The unaccompanied women were berthed in the stern. They all died in their beds.

Below deck, the surviving passengers made a frantic rush to the stairwells, which were soon jammed. Within minutes, the unstable ship started listing to port, away from the land. The bow slid off the rock onto an underwater ledge, and the ship came to a stop at a sharp angle. With the deck facing the oncoming waves, most of those who had managed to claw their way up were washed into the frigid water, which poured down the stairwells, drowning nearly everybody in the family quarters. With all the lifeboats destroyed, the captain urged crew and passengers to climb the rigging as the ship sank by the stern. Those in the bow clutched the rail as the ship rolled; then they climbed onto the side of the slanting hull.

Now, as Clancy peered through the night at the hundreds of people clinging to life, he knew he needed to get help before more of them perished.

Clancy rushed home, where his daughter, Sarah Jane O’Reilly, had given Robert Thomas dry clothes and a chair next to the stove. He was the first in a throng of people about to seek refuge in Clancy’s house. Clancy sent eleven-year-old Eddie Mullins to awaken the nearest neighbour, Edmund Ryan, who lived with his wife, Elizabeth, and their three children on nearby Ryan’s Island. Both Meagher’s Island and Ryan’s Island were part of the community of Lower Prospect, whose main settlement lay on the adjacent mainland.

Through the darkness, Eddie rowed his little boat across the cove, watching the outline of the trees against the western sky to find his way. When he reached shore, forty-nine-year-old Ryan was already on the move, having heard the crash and seen the distress rockets. He had rounded up the neighbours to help in whatever rescue effort would be needed. He fired his musket a couple of times to alert the people on the mainland that something was afoot.

It was around 4:30 a.m. when Ryan arrived on Meagher’s Island. As more fishermen gathered, they decided to attempt to rescue the men on the rock using a wooden dory. But the seas were too rough for the small rowboat, and the two men aboard nearly lost their own lives. The rescuers needed a larger and more seaworthy boat.

Fortunately, James Coolen, who lived on the mainland, soon arrived at Clancy’s wharf with his eight-metre seine boat, used during the summer to catch herring and mackerel. With its rounded sides, it could be tipped almost to the rails to scoop the catch out of the net. It was ideal for picking men out of the water. This was all the more urgent, as some of the people clinging to the sinking ship had begun to fall into the cold, turbulent water.

Given the agitated state of the sea and the distance around Meagher’s Island to the wreck site, Coolen’s heavy boat — weighing some three hundred kilograms — had to be dragged across the island from Clancy’s sheltered wharf to the exposed side, where the waves were pounding the wreck. A few survivors had managed to get ashore, and they helped the locals to manhandle Coolen’s boat uphill over brush-covered boulders the size of beach balls, then to drag it down the other side of the hill and into the huge waves that pounded against the shore, drenching them all with bone-chilling spray. At 6:00 a.m. Coolen and a crew of local oarsmen began rescuing men, eight or ten at a time, from the offshore rock and bringing them to safety on Meagher’s Island. Time was of the essence: The tide was coming in, and in a few hours the ocean would submerge the rock and sweep away the men sheltering there. Once ashore, the rescuers had to get the shipwrecked men out of the boat and onto land without demolishing the boat — or injuring the survivors.

While picking up a load of men, one of the rescuers — Edmund Ryan’s brother Dennis Ryan — glanced towards the shore and was relieved to see another seine boat being lugged over the crest and down towards the water. In the gang labouring at it were the O’Brien brothers, James and Michael Jr., and Tom Twohig, a strong young fellow from Pennant on the nearby mainland who was courting the O’Briens’ sister, Kate. By 6:30 a.m., they had the boat in the water and had joined in the rescue, this time taking survivors off the ship, while the captain directed the orderly evacuation from his post onboard.

Advertisement

Come the dawn, those at the wreck site took in the extent of the disaster. There lay the Atlantic, nearly turned over, broken and awash. The stern was underwater, as were the portside rails. Four huge steel masts pointed out to sea, like long cannons on a battlefield. Clustered upon the bow, which remained just above the waves, were most of the surviving men. The rest, about thirty-two people, were clutching the rigging of the mizzen-mast, the third mast back from the bow. Its base was submerged, so they were trapped with no shelter from the bitterly cold winds. Charles Flanly of Paterson, New Jersey, was one of them. He was just seventeen or eighteen years old, travelling from Ireland. The only woman still alive, Rosa Bateman, was also in the rigging. Dressed only in her nightclothes, she had told her husband, James, that she could not go any further and urged him to save himself. He did. Flanly wrapped his jacket around her and did his best to comfort her.

Back onshore, Michael Clancy’s house was so jammed with suffering survivors that Clancy had to bore holes in the floor to drain the water that was dripping off them. Describing the scene later to a New York Tribune reporter, a tearful Clancy spoke “of the drowning, of the shrieks, of the moans, of the haggard, frenzied, half-crazed people who crowded into his house.”

Sarah Jane O’Reilly and her sister Elizabeth Clancy were hurriedly feeding fuel to the stove and boiling water, scrounging for dry clothing and stretching their meagre resources. Though she was, as the Halifax Daily Echo newspaper wrote, a “little slip of a woman, being ... only five feet in height,” O’Reilly maintained order and kept things moving. More than anything, these men had to be warmed up, so there was a constant rotation around the stove. Many had left their berths without time to dress, although some had managed to salvage clothing from the dead who had washed ashore.

“As fast as the men were rescued, they were brought to the house and cared for, and from there to the mainland in small boats,” O’Reilly later wrote. “Seventy-five of them stayed with us in the house overnight.” The others were taken in by families throughout the community.

With 8:00 a.m. approaching, about 230 men had made it ashore, but a few hundred more were still marooned on the rock and the ship. The two rescue crews were stressed. They regularly swapped men in and out of the boats; but, while the rescuers welcomed a respite from the hard work, stopping only made them colder.

In the nick of time, a boatload of men arrived from Upper Prospect, a community about five kilometres away. Among them was Nicholas Christian, a prominent businessman and justice of the peace who had been awakened at dawn by his brother Patrick with a story that a ship was aground at Meagher’s Island. At first he had been reluctant to believe his brother, because it was April Fool’s Day.

The fishermen took the last man off the rock just a few minutes before the tide came in and submerged it. By around 9:00 a.m., the fishermen had saved everybody who had been trapped on the rock and on the bow of the wrecked ship, including eleven-year-old John Hanley, the only child to survive. With only seventeen people left on the ship, Captain James Williams was carried, exhausted, off the destroyed liner and placed into a rescue boat. He had previously been implored to leave the ship but refused. “I feared that the captain would drop off from exhaustion and fatigue,” passenger Nicholas Brandt later recalled.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

At last only two men were left in the rigging, Chief Officer John Firth and the New Jersey teenager Charles Flanly. Rosa Bateman — the only woman to survive beyond the first few minutes of the shipwreck — had died of exposure. But the sea conditions had become too hazardous for the rescue to continue. “The wind, sea, and tide were too high when the boats ceased running to rescue the first officer and the other man who were in the mizzen rigging,” Nicholas Christian, one of the rescuers, later testified. “A boat in which my brother John was, made the attempt, was struck by a heavy sea and nearly lost, and had to abandon it.”

Around noon, William Ancient, the Anglican clergyman from the nearby community of Terence Bay, arrived at the scene of the wreck. The tide was going down, and the weather was calmer. Along with a boat crew, he rescued Firth and Flanly around 3:00 p.m. “The last two men saved were benumbed with cold and could not have lived much longer; one was put to bed. I gave the other hot drinks and told Mr. Ryan to take the man to his house, as our house was packed full and could not hold another person,” Sarah Jane O’Reilly later wrote.

By dusk, the Atlantic finished turning onto her side and lay just beneath the waves. Death had visited all of the women on the ship, all of the children except John Hanley, and all of the married men except two. In addition to Rosa’s husband, James Bateman, young William Glenfield was also alive. He had become separated from his brand new wife, Annie, and spent two days looking for her as the bodies came ashore. He never found her, but one of the searchers recovered her suitcase. By the time it got to him it had been rifled through, and all Glenfield had to remember her by was a pair of her slippers.

Meanwhile, the Atlantic’s ever-resourceful third officer, Cornelius Brady, after swimming ashore and working throughout the rescue, walked for eight hours to Halifax to report the loss of the ocean liner. That evening, William S. Fielding, a young reporter from the Morning Chronicle, tracked him down and wrote a story that began: “It is our painful duty this morning to record the most terrible marine disaster that has ever occurred on our coast.” Fielding described Brady as “bruised, worn out and almost speechless after the terrible events of the morning.”

Over the next couple of days, steamships took the approximately four hundred survivors to Halifax, and from there they departed for New York on passenger ships and trains. The identifiable Roman Catholic dead were buried at Lower Prospect near the Star of the Sea Cemetery, with the Protestants and others of undefined faiths going to Terence Bay next to St. Paul’s Anglican cemetery. All told, about 550 people died. A small number of bodies got shipped to family in the United States, and at least four were buried at Camp Hill Cemetery in Halifax.

On April 5, the Morning Chronicle appealed to the authorities to help those who had so bravely rescued the shipwrecked. Almost all of the rescuers were people of Irish descent, whose parents and grandparents had come to Newfoundland or Nova Scotia in poverty, often as indentured servants for fishing companies: “The fishermen’s families gave all the provisions they had to the shipwrecked people, and in many instances are now themselves in actual want. There could be no better way to manifest sympathy in the matter than to send down to Prospect a quantity of provisions to refill the larders which were so cheerily emptied to feed the distressed people. This is an important matter, and should be attended to at once.” As soon as the news of the wreck hit Halifax, the legislature met and voted to spend whatever it took to see to the needs of those affected.

On April 5, an inquiry was convened in Halifax under the collector of customs, Edmund McDonald, to determine the cause of the disaster. The evidence given described the SS Atlantic’s stormy crossing and the fuel shortage. It also supported Captain Williams’ decision to divert to Halifax.

Testimony revealed that at midnight, before going to sleep, Williams gave orders to the senior officer of the watch, Second Officer Henry Metcalfe. Like the captain, Metcalfe had never been to Halifax. Williams told Metcalfe that the first indication that they were getting close to Halifax would be the sighting of the Sambro lighthouse, which should be visible by 3:00 a.m. He instructed Metcalfe to wake him as soon as the light was sighted. If Metcalfe did not see the light by 3:00 a.m., he was to wake the captain anyway.

Fully clothed, Williams went to sleep on a cot in the chart room behind the man at the helm. One o’clock came with nothing to report; two o’clock was the same. Three o’clock arrived, and there was still no sign of the light. Assuming they still had some distance to go, Metcalfe decided to let the captain sleep. The Atlantic continued at full speed, with five lookouts staring into the blackness.

Five minutes after three, ten after, a quarter after — crash! In clear conditions, this two-year-old ship, with everything working perfectly, using the latest Admiralty charts, being commanded by officers from the world’s leading seafaring nation, wrecked off Meagher’s Island with tragic consequences.

Captain Williams was found at fault for being asleep while coming into a strange port. Contrition and sorrow marked his reaction to the loss of the Atlantic. He made no excuses and did not criticize Second Officer Metcalfe. “What more can I suffer? If it were not for my wife and three little children at home, I should never have been here; I’d have stuck to that vessel till the last and gone down with her,” Williams later told the Halifax Novascotian.

Williams lost his extra master certificate — the highest designation for a British master mariner — for two years. He would have lost it for life had he not made a heroic effort during the rescue. The suspension spelled the end of his life on the sea. He became an innkeeper in Manchester, England.

The fourth officer, John Brown, lost his certificate for three months. He really was not at fault but had the misfortune of being the junior officer standing the watch. The officer in command of the ship, Second Officer Henry Metcalfe, died in the disaster. To dig up details of his failings was considered unseemly, so the inquiry was inconclusive as to his culpability in the affair.

What was the ultimate cause of this great calamity? The western Atlantic Ocean around Nova Scotia is greatly affected by the record tides generated in the Bay of Fundy. Based on the captain’s testimony, the inquiry concluded that, unknown to anybody aboard, a current had pushed the Atlantic off course by about fifteen kilometres. If she had been on course, the ship would have entered the ten-kilometre-wide mouth of Halifax Harbour, where three additional lighthouses would have become visible to guide the sailors. But the ship was too far west. Had Metcalfe taken a sounding of the depth, he would have realized that they were closer to the coast than he had assumed. But he did not. And so the ship struck the Chebucto Peninsula while passing the Sambro light, which — despite the overall clear conditions — was probably shrouded in patchy fog, a weather phenomenon that is common in the area.

Advertisement

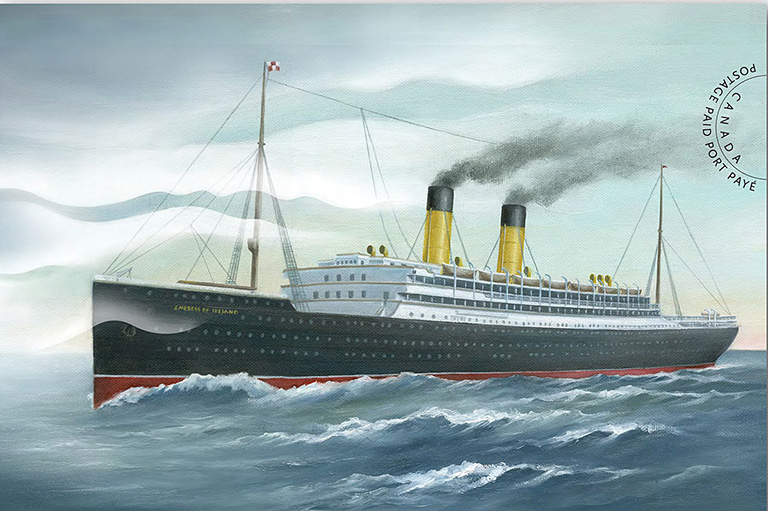

The wreck of the Atlantic was the biggest transatlantic passenger ship disaster of the nineteenth century and the most terrible to occur anywhere in Canada until the Empress of Ireland sank in the St. Lawrence River in 1914 with the loss of more than one thousand lives. The two shipwrecks still rank as numbers one and two, in terms of loss of life, in Canadian waters.

The Atlantic disaster also predated by thirty-nine years the sinking of another, more infamous White Star liner — the RMS Titanic. Yet a line can be drawn between the two disasters. Under its visionary owner Thomas Ismay, White Star started the transition of its fleet from strictly sailing ships to primarily steamships in 1870 by ordering its four transformational steamships — Oceanic, Atlantic, Baltic, and Republic— from the talented Edward Harland of Harland and Wolff, in Belfast.

The Atlantic and her sisters heralded a time of great change in ship design. They were bigger, faster, and more sophisticated than most steamships of the day. However, the ability to look at a dial on the bridge for basic information like speed and water depth lagged behind the improvements in ship speed and size, and knowing what lay ahead of these large, fast ships would depend on human eyesight until radar was introduced on ships halfway through the Second World War. The inevitable finally happened in 1912, when Harland and Wolff’s latest creation, the bigger and much faster Titanic, struck an iceberg while the lookouts peered into the darkness — exactly as they had on the Atlantic— and 1,500 people perished.

The Titanic story is well-known. It has been retold countless times in movies, books, and museum exhibitions. Three hundred and thirty Titanic victims were recovered on the high seas more than a thousand kilometres from Canada by ships that set out from Canadian and Newfoundland ports. Half of the people who died were buried at sea, while one hundred and fifty bodies were landed at Halifax and buried there. Over time, that effort has become magnified in some Canadian minds to the point where tourists visiting Nova Scotia get the impression that the Titanic disaster was somehow a Nova Scotia disaster. Thousands of people visit the grave sites annually. The government of Canada has erected a bronze commemorative plaque at the largest of the three Titanic burial sites in Halifax.

The story of the Atlantic, by contrast, is barely remembered, despite being the second-worst shipwreck in Canadian history. Nearly four hundred survivors were rescued by Canadians — not on the high seas a thousand kilometres away but on the Nova Scotia shoreline — and taken into their homes, where they were mended, fed, and clothed. Then these same Canadians recovered five hundred and fifty bodies and buried them near their homes.

In 2017, the SS Atlantic Heritage Park Society, a volunteer group that maintains the gravesite of 277 of the more than 500 victims buried in Terence Bay and Lower Prospect, applied to the National Sites and Monuments Board of Canada to have the Atlantic disaster declared a national historic event. The application was turned down, with the observation that the board “could not identify any change to some facet of Canadian society, such as changes to social programs, public policy, or longstanding economic impacts.”

But perhaps the significance of the wreck of the SS Atlantic was best expressed by W.S. Fielding, the young reporter who first broke the story of the catastrophe: “The courage of the fishermen of Prospect, who hurried to the scene of the wreck in their boats, and risked their lives to save the men of the Atlantic, their hospitality displayed in opening their houses to the distressed, and sharing out their scanty wardrobe among the naked, and all this generously; the action of the Legislature on behalf of the Province, and of the Mayor on behalf of the city — in at once offering shelter and food to the sufferers — evinced effectively the sympathy for the living and the sorrow for the dead felt in every section of the country upon whose rocks the Atlantic was cast away.”

Related

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement