The Ballots Question

Every incoming train is carrying them, farmers, artisans, merchants, business and professional men, and a substantial sprinkling of women. Already the hotel corridors ... and the streets are bright with their red badges. All parts of the Dominion are rubbing shoulders. — Harry W. Anderson, Toronto Globe.

August 1919. Thousands of men and women were coming to Ottawa for what the papers called “the largest political gathering in Canadian history.” As delegates to a Liberal Party leadership convention, they took part in all the rituals of Canadian party leadership: last-minute withdrawals, dramatic shifts of support, multiple ballots.

The candidate who got the prime-time speaking slot went far over his allocated time — and was rewarded with rapturous cheering from frenzied supporters. On the last day, the first-round leader hung on grimly to a razor-thin victory. Everyone went home declaring the party had built a winning platform and was more united than ever.

But this convention was something new. Never before had a party leader been chosen by thousands of ordinary Canadians. This was the first party leadership contest ever held in Canada — the ancestor of all that followed, from the epic contests won by John Diefenbaker, Pierre Trudeau, and Brian Mulroney to the more recent selections of Justin Trudeau and Andrew Scheer.

The 1919 convention that made William Lyon Mackenzie King a prime minister-in-waiting created a model that still defines how Canadians think about power, politics, and the accountability of prime ministers and premiers.

INVENTING THE LEADERSHIP CONVENTION

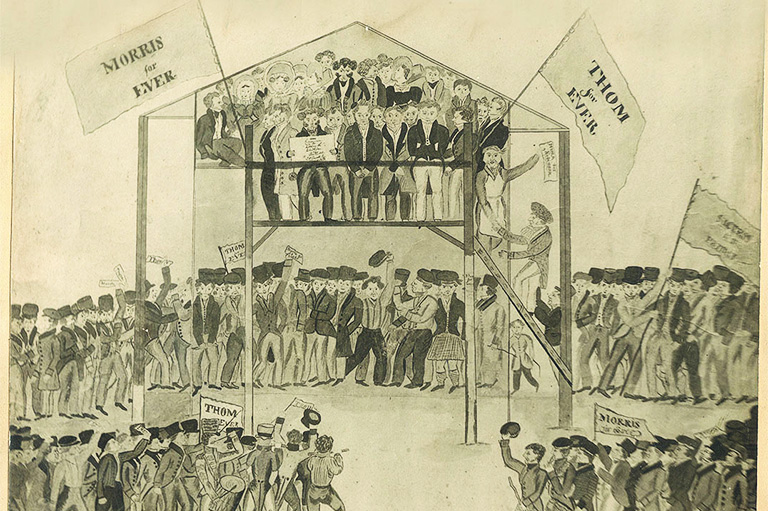

In the first fifty years of Confederation, there were no leadership conventions. Sometimes a Governor General or lieutenant-governor determined leadership by deciding who should be asked to form a government. Most often, the parliamentary caucus of a party’s elected members decided whom it wanted to support — or to remove.

In 1887 the Liberal Party caucus made Wilfrid Laurier party leader. In 1896 Conservative Members of Parliament and cabinet ministers forced Prime Minister Mackenzie Bowell out as party leader and as prime minister.

In 1910, just a year before he became prime minister, Robert Borden faced a formal vote of his caucus on whether or not he would be removed from the party leadership.

Then, at the end of the First World War, the Liberal Party faced a crisis. In 1917, Prime Minister Robert Borden’s promise to win the war at any price — including conscription — had split the Liberal Party wide open.

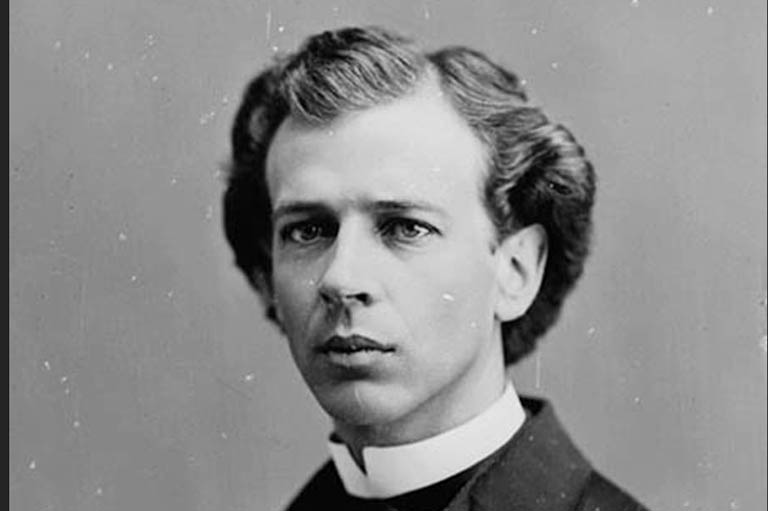

Leading Liberal MPs from English Canada joined Borden’s Union government, leaving Laurier, the aging Liberal leader, with a small, mostly francophone caucus. As the war ended, Laurier urgently needed to bring his party back together.

In November 1918, a week after the armistice, Laurier announced that the Liberals would hold a national convention to make new policies for the postwar world. But Laurier died suddenly in February 1919.

Looking about for new leadership, his bereaved followers agreed that only an English-speaking Liberal could rebuild the party. All the strongest prospects, however, were still in the Union government or sitting as independents. So the party’s MPs decided not to decide.

Days after Laurier’s death, the Liberal caucus announced that the convention already in the works for August 1919 would become a leadership convention. For the first time ever, thousands of rank-and-file party members would be invited to choose a party leader.

One tradition established in 1919 was the way Canadian political parties usually hold their most important gatherings in hockey rinks or cow palaces.

Laurier, who had a radical streak, had loved to boast that his party was democratic and responsive to the people. “It was therefore fitting that his successor should be chosen not by a coterie of politicians but by a great democratic convention,” one of Laurier’s loyal MPs, Samuel Jacobs of Montreal, soon declared.

But Laurier had never committed himself to making the 1919 gathering a leadership convention. It was the Liberal MPs and senators — without much debate and with little more than a vague sense that a vote by many people must be more democratic than a vote by a few — who made the decision, driven mostly by the leader’s sudden death and the urgent need to broaden the ranks.

A CONVENTION IN A CATTLE BARN

The Liberals held their convention mid-week, from Tuesday to Thursday, to allow for the days many delegates would spend riding trains to Ottawa and then home. In most other ways, this first leadership convention set patterns that endured in future Canadian party leadership races.

One tradition established in 1919 was the way Canadian political parties usually hold their most important gatherings in hockey rinks or cow palaces. In Ottawa, the venue was Lansdowne Park, and particularly Howick Hall, which had more often hosted agricultural exhibitions.

The hall had been decorated for the event with banners, flags, and potted palms, and the platform was dominated by a brightly lit portrait of the dead leader. It also boasted such innovations as telephones for delegates and the press, a restaurant able to feed 1,200 people at a seating, and, should hotel space be insufficient, an eighthundred- bed delegates dormitory.

Facilities for sixty journalists were provided, and stenographers would keep a record in both French and English.

Of the 1,005 voting delegates and 650 alternates, the largest numbers came from Ontario and Quebec; but there were several hundred each from the West (including Yukon Territory) and the Maritime provinces.

According to a Toronto Globe reporter, “The majority of men who represent the older provinces are men of mature years.… But from the prairies, the vast predominance are young men, some in their twenties and early thirties.”

With Canadian women having just secured the same voting rights as men, women were delegates, too. There were only fifty or so, but each was applauded as she took her seat. It was “on account of the presence of ladies” that the delegates were asked to refrain from smoking in Howick Hall.

The convention’s voting system would influence all future Canadian leadership races. Though the Liberals supported federalism and the rights of the provinces in national politics, they rejected the American system of having the convention vote in public, state by state. Secret ballots, with one vote per delegate, would determine this race.

The Liberals spent two days of their three-day meeting in 1919 debating the great issues of the day. With Canada seeking national status at the Paris Peace Conference, a Liberal policy statement on Canada’s relationship with Britain and imperial relations had to be hammered out. Canada’s wartime army was flooding home, and delegates in uniform were cheered as they advocated for the needs of returning soldiers.

Just weeks after the traumatic general strike in Winnipeg (to which the leaderless Liberals had barely responded), industrial relations commanded urgent attention.

Tariff policy needed careful handling, as the Liberals struggled to balance their free-trade principles against the enduring popularity of protection for Canadian industries.

The newly introduced Income Tax Act sparked a resolution assailing the government for not enforcing it strongly enough.

Yet the new leader, once chosen, would not feel particularly bound by the policies for which the delegates had voted. The resolutions would be more like guidelines.

At least, observed Quebec City MP Charles Power, who attended the 1919 debates, “it leaves the impression that the rank and file have had their say.”

Party leaders have said much the same ever since. What really mattered in 1919 — and has mattered most at party conventions ever since — was choosing a leader.

THE CHOICE

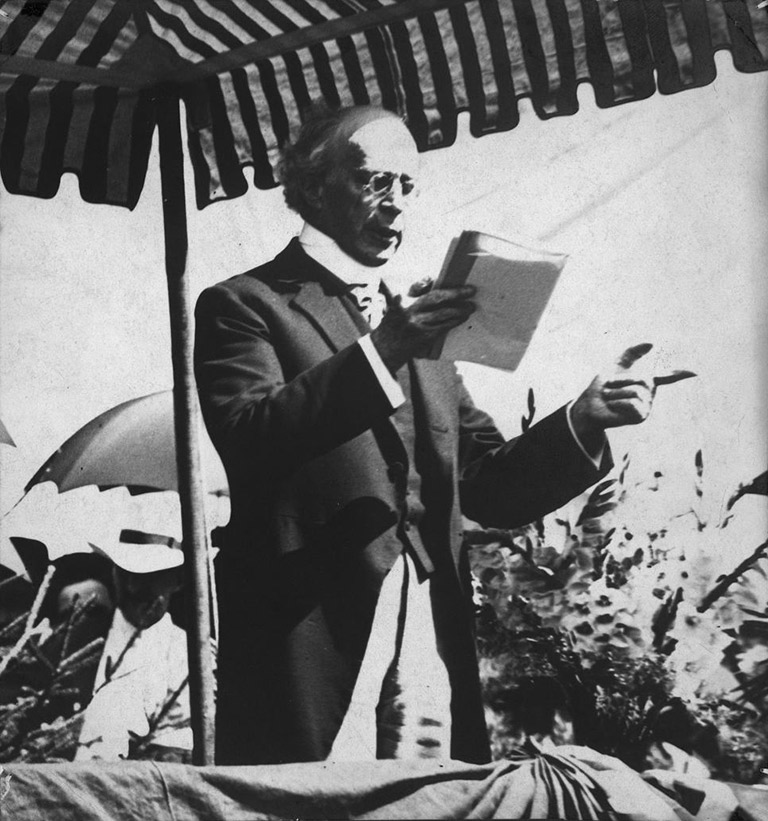

There was no drawn-out nomination race in the months preceding the convention. Campaigning was frowned upon, and there would be no official nominations until the morning the vote was held in Howick Hall. There were no big speeches from the candidates, either, though Mackenzie King, moving a policy resolution the night before the nominations, broke the rules and roused the hall with a long campaignstyle tribute to Laurier.

Nevertheless, William Stevens Fielding had been the front-runner ever since Laurier’s death. Fielding was a veteran Liberal, once premier of Nova Scotia and then the federal finance minister during the prosperous Laurier years. The “little grey man” was the strongest of the old Liberal team, a smooth parliamentary performer with an extensive network in the party. He attracted the support of establishment Liberals and the business community.

But Fielding had two big problems. He was seventy, not that much younger than Laurier. Worse, he voted for conscription in 1917 and left the Liberal caucus to sit as an independent MP. The presumed front-runner was not even a member of the party caucus. Yet rumour had it that Laurier had forgiven Fielding and favoured him as a stopgap leader who would bring wartime defectors back into the fold, pending the emergence of new, younger men.

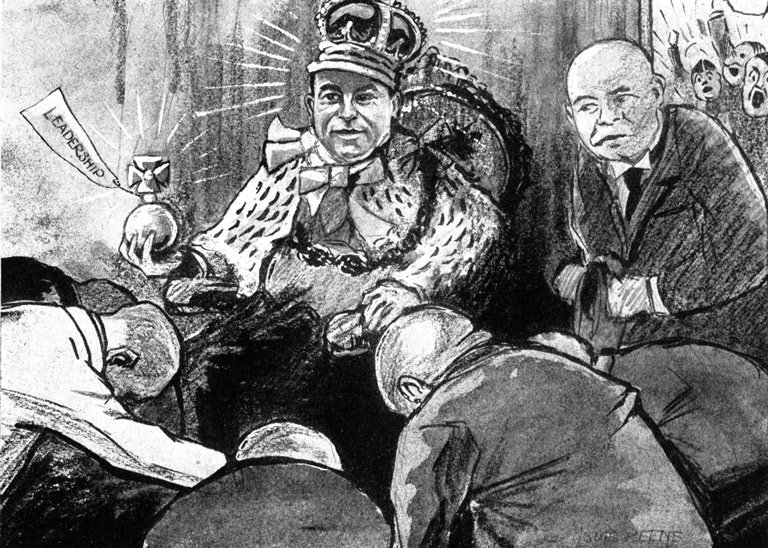

William Lyon Mackenzie King believed he was that new blood, and also that he was Laurier’s destined heir. Few others thought so. At forty-four, King was the youngest candidate in the race to lead the Liberals, but he had twice failed to get elected and had spent the war out of uniform and working on labour relations for the Rockefeller interests in the United States.

Maclean’s journalist J.K. Munro had called Fielding the joker in the pack, because he was not in the caucus, but dismissed King as “the joke,” not a serious contender at all. King, always alert to conspiracies, muttered to his diary that “the big interests” were plotting against him in hotel suites stocked with liquor.

The other candidates were close to Fielding in age and background, and many of their supporters seemed likely to turn to him as a second choice.

Only Sydney Fisher, one of the few anglophones left among Liberal MPs, posed a threat. Listed as a farmer, he was in fact a wealthy landowner in Quebec’s Eastern Townships. He understood the French Canadians’ visceral opposition to conscription.

Loyal to Laurier, he refused to reconcile with Fielding, the former friend who had abandoned the leader.

The manoeuvring really began with a gathering of the Quebec delegates. Quebec Premier Jean-Lomer Gouin presumed that he could tell them how to vote — and he favoured Fielding, who shared his conservative businessminded outlook.

When the delegates protested against supporting a conscriptionist, Gouin switched tactics: Since the convention winner was going to be an anglophone, the Quebeckers should abstain and leave the choice to les anglais. It was a ploy to ensure a Fielding win, and the francophone delegates rebelled. But whom to support? Fisher was old and uninspiring, and they hardly knew Mackenzie King.

Fisher went to the Rideau Club, Ottawa’s fabled centre of power and intrigue, to have lunch with two old Liberal barons: Allen Aylesworth from Toronto and Senator Raoul Dandurand from Montreal.

The manoeuvring really began with a gathering of the Quebec delegates. Quebec Premier Jean-Lomer Gouin presumed that he could tell them how to vote — and he favoured Fielding, who shared his conservative businessminded outlook.

When the delegates protested against supporting a conscriptionist, Gouin switched tactics: Since the convention winner was going to be an anglophone, the Quebeckers should abstain and leave the choice to les anglais. It was a ploy to ensure a Fielding win, and the francophone delegates rebelled. But whom to support? Fisher was old and uninspiring, and they hardly knew Mackenzie King.

Fisher went to the Rideau Club, Ottawa’s fabled centre of power and intrigue, to have lunch with two old Liberal barons: Allen Aylesworth from Toronto and Senator Raoul Dandurand from Montreal.

If both he and King ran, Fisher said, they would split the vote. Fielding would win. He proposed to drop out and nominate King himself, seconded by Ernest Lapointe, the MP who had led the Quebec delegates in revolt against Gouin’s machinations.

No, counselled Dandurand. Two Quebec MPs nominating Mackenzie King might spark an anti-Quebec backlash that would help Fielding. Let Aylesworth, not Lapointe, second the nomination. It would show the Quebeckers that King had serious support in Ontario and could win.

Aylesworth had left public office because he had become deaf, and Dandurand did not dare to shout out this proposal to him in the Rideau Club dining room. He scribbled it out on a scrap of paper, and Aylesworth scrawled an emphatic yes.

Suddenly, King — dull, pedantic, and fussy as he was — had solid support in the Quebec and Ontario delegations as well as with the Laurier loyalists elsewhere. The next morning, he led from the first ballot and hung on to beat Fielding narrowly on the third.

CHANGING LEADERSHIP FOREVER

If selected, William Fielding had said, he would convene a caucus meeting to make the convention’s leadership choice official. He also said he could not be bound by the delegates’ policy resolutions. King was astute enough not to dismiss the resolutions so openly, but for the 1921 federal election he would indeed set out his own platform.

King never for an instant considered asking the party caucus to ratify his leadership. His uncanny political instincts told him instantly what selection by a convention vote offered a party leader: It meant power.

After choosing King, the 1919 Liberal Party convention dissolved. As leader and, later, prime minister, King would never have to answer to thousands of delegates, for he would call no more Liberal conventions until he retired in 1948.

He would not consider himself accountable to his caucus, either. As well-connected observer John Lederle noted, King “placed great stock in the fact that he was selected by a democratic convention and not by the parliamentary caucus.”

Without that accountability to the caucus of elected MPs, a prime minister with a majority government may do whatever he or she pleases for years at a time.

As prime minister, King “has more than once silenced the parliamentary wolves,” Lederle wrote, “by emphasizing that he is the representative and leader of the party as a whole, not merely of the parliamentary group. What the parliamentary group did not create it may not destroy.”

King was determined that MPs would answer to him, not the other way around. “Parliament will decide,” was King’s response to most problems. He knew that as long as his docile MPs formed the majority Parliament would decide what he wanted it to decide.

In 1920, when Arthur Meighen became Conservative Party leader, and therefore prime minister, he was also the last Canadian party leader chosen by a parliamentary caucus.

Liberal MPs mocked him as “not elected in open convention, as we consider to be the custom in a democratic country.” King might have smiled: He already knew that open convention voting had left him accountable to practically no one.

For decades, as in 1919, most convention delegates continued to be hand-picked, loyal followers of the party line. It was John Diefenbaker — like King a loner convinced of his destiny — who grasped that by campaigning at party gatherings across the country he could bring his own loyal delegates to the Conservative convention of 1956 and outvote the establishment and the MPs.

Eventually, would-be party leaders, some without much parliamentary or party experience at all, began raising millions of dollars for party leadership campaigns based on the selling of memberships.

Once online membership sales and digital voting took hold, delegates became as obsolete as MPs: Hundreds of thousands of party members could vote directly for leaders. Those members’ power, however, nonetheless vanished the moment the convention adjourned.

In the rest of the parliamentary world, the Canadian idea of leadership selection has never really caught on. Parliamentarians elsewhere argue that democracy depends not just on how many votes are cast but on accountability.

In Japan, in Ireland, in Britain, MPs have asserted their right to remove a failing party leader and to choose a successor. Otherwise, they insist, the root principle of parliamentary government — leadership constantly accountable to elected representatives accountable to the people — breaks down.

Without that accountability to the caucus of elected MPs, a prime minister with a majority government may do whatever he or she pleases for years at a time.

For one hundred years, that vision of accountable leadership has had little appeal in Canadian politics. Canadian party leaders — of all parties, both federal and provincial — have grown steadily more confident in overruling cabinet members, driving “disloyal” MPs out of politics, and relying mostly on unelected advisors to make and to sell the party message.

That tradition goes directly back to the Liberal Party convention of 1919. So far, it shows few signs of changing.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Wouldn’t your magazines like to slip into something more comfortable?

Preserve your collection of back issues with this magazine slipcase beautifully wrapped in burgundy vellum with gold foil stamp on the front and spine. Holds twelve issues.