The Priest Who Shaped a Province

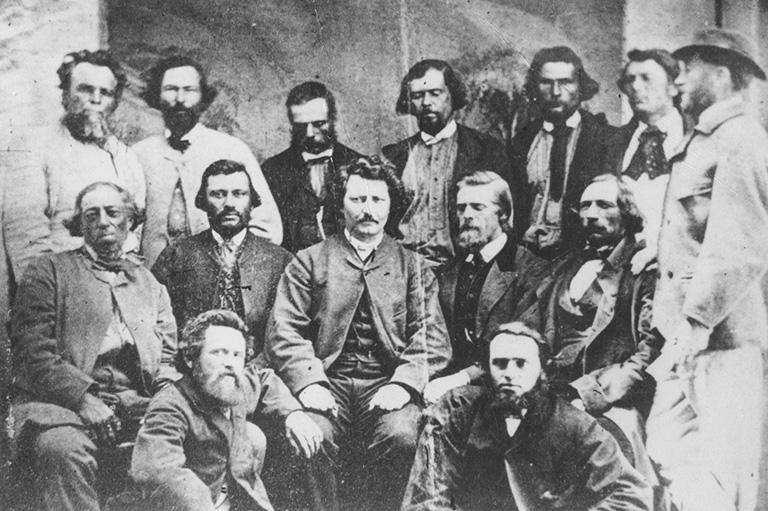

On the south grounds of the Manitoba legislative building stands a larger-than-life statue of Louis Riel that recognizes the Métis leader’s pivotal role in the creation of Canada’s fifth province.

In its literal shadow is a bronze National Historic Sites and Monuments Board plaque commemorating Noël-Joseph Ritchot, the Red River missionary who actually negotiated Manitoba’s entry into Confederation.

Although his role was almost equal to that of Riel, Abbé Ritchot, despite being Riel’s éminence grise, rarely merits more than a brief historical footnote. Baptized as Joseph-Noël, he also signed as Noël or N.J. He was deeply involved with the Red River Settlement’s activist Métis before Riel became their leader and the voice of the resistance to Canadian rule.

From the summer of 1869, when he first helped to legitimize and to support Riel’s emergence as a leader, and continuing until the latter’s departure for Montana, Ritchot acted as Riel’s trusted confidant, mentor, chief diplomat, advocate, and lobbyist.

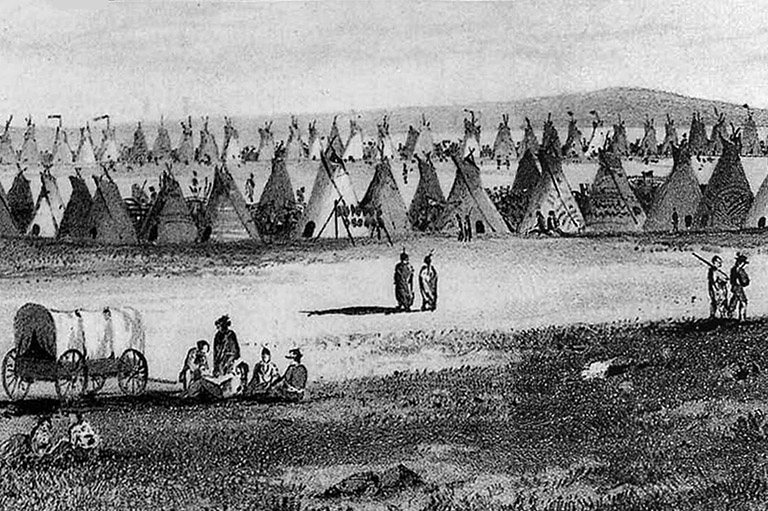

The Red River Settlement of the 1860s was no longer an isolated fur trade outpost. The old water routes to York Factory on Hudson Bay and to Montreal had been superseded by ox cart trails to St. Paul, Minnesota.

The communal Métis bison hunts that once saw hundreds of two-wheeled Red River carts return to Fort Garry laden with pemmican were now having difficulty locating the ever-diminishing herds. Years of drought and grasshopper infestations devastated the settlement’s river-lot farms that stretched three kilometres back from the water.

The demographics of the settlement were changing as well. The predominantly Métis parishes, both English- and French-speaking, had grown steadily since the initial wave of laid-off fur trade employees was invited to settle at the Forks — the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers in what is now downtown Winnipeg — by the Hudson’s Bay Company after it merged with the North West Company in 1821. By the 1850s, agricultural land had become harder to find in Upper Canada.

The prairie west, “empty” save for the First Nations peoples, the Métis, and the fur traders who lived there, in some cases for many generations, became a tempting new frontier for Upper Canadian ambitions. These newcomers trusted that the lands they occupied with the permission of the HBC would soon become part of Canada.

Many took up farming near Portage la Prairie, about fifty kilometres to the west of the Red River Settlement. Commercially minded settlers began to expand the small village of Winnipeg where the Portage Trail met Main Street, about a kilometre and a half north of what is now known as Upper Fort Garry.

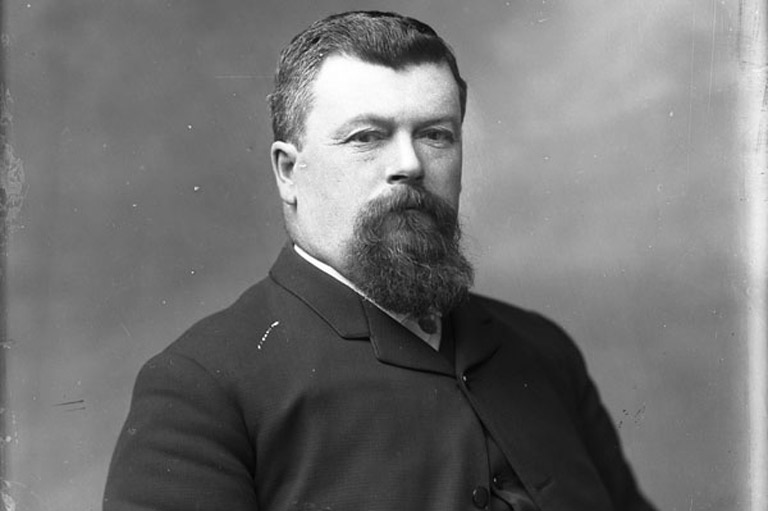

The self-styled Canadian Party, a new movement led and embodied by Dr. John Christian Schultz and the newspaper the Nor’Wester, took shape. An imposing figure, Schultz personified the Anglo-Ontarian intolerance of all things Catholic and French that had made Canadian politics such a balancing act in the 1850s and 1860s.

He was a bombastic supporter of union with Canada who had little but contempt for the HBC and most of the long-time residents of the Red River Settlement.

Fear of a “second Quebec” to the west lurked in the minds of many Ontarians, both those who still lived in the province and those who had moved to Red River. The arrogant and disrespectful “Canadas” — members of the Canadian Party — were contemptuous of local HBC authorities, to the point of organizing what they described as the liberation of prisoners they felt had been jailed unfairly.

In the words of historian George Stanley, “They challenged the Company régime, they ridiculed it, they refused to obey its orders, they tore the trappings of dignity from it, they bared its nakedness and revealed its puny muscles.”

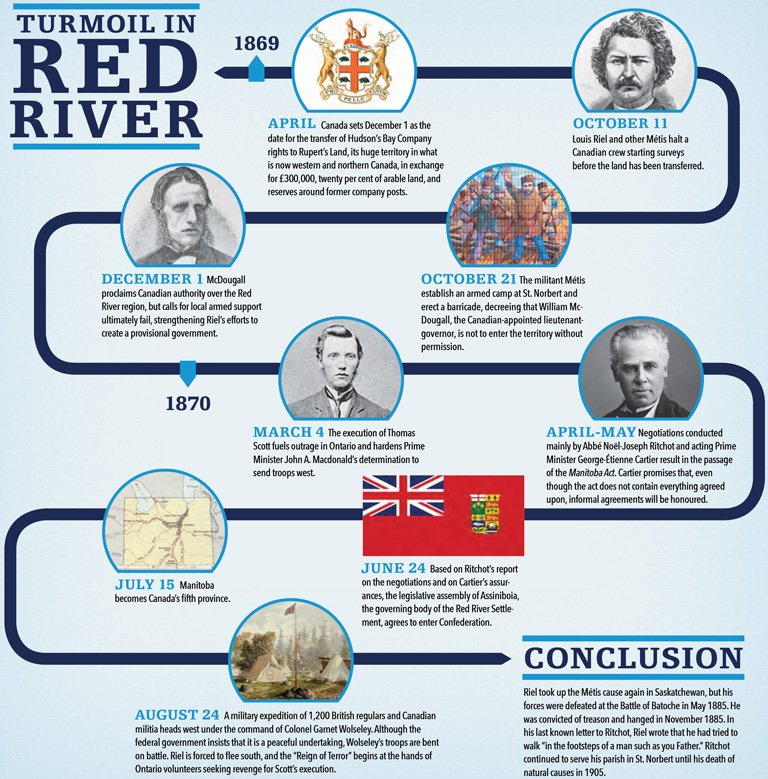

The British North America Act of 1867 had made provision for the new Dominion to acquire the region. After all, the dream of a British North America, bonded by railways stretching from Nova Scotia to British Columbia, could only be fulfilled by acquiring the vast territories known as Rupert’s Land that belonged to the HBC.

As the company’s stockholders saw a way to reap profits through real estate as opposed to furs, serious discussions between Canada and the HBC approached their culmination in the spring of 1869. As Canada prepared for the transfer, no one on either side of the Atlantic saw fit to let the ten thousand-plus residents of the Red River Settlement know how the Dominion would treat them, their landholdings, or what they saw as their rights and customs.

The behaviour of Prime Minister John A. Macdonald’s administration confirmed the poor regard in which Canada was already held among the original residents of Red River. When starvation threatened the settlement in 1868, Canadian “aid” took the form of a crew sent to build the Dawson Road, which would link the settlement to Lake of the Woods for the benefit of colonists from Canada.

The crew’s arrival and mission were a complete surprise to local HBC authorities. The Métis employed on the project were paid in vouchers, which were redeemable only at the store owned by the hated Schultz and at its inflated prices.

Details of the transfer of HBC lands to Canada came into the settlement either through the pages of the Nor’Wester, which extolled the move, or via the annexationist press in St. Paul, which predicted dire consequences for the original settlers.

By late in June 1869, tension had become particularly high among the French Métis, who felt especially vulnerable and maligned by the Canadas. They found sympathy, support, and guidance in the curé of St. Norbert, Abbé Noël-Joseph Ritchot.

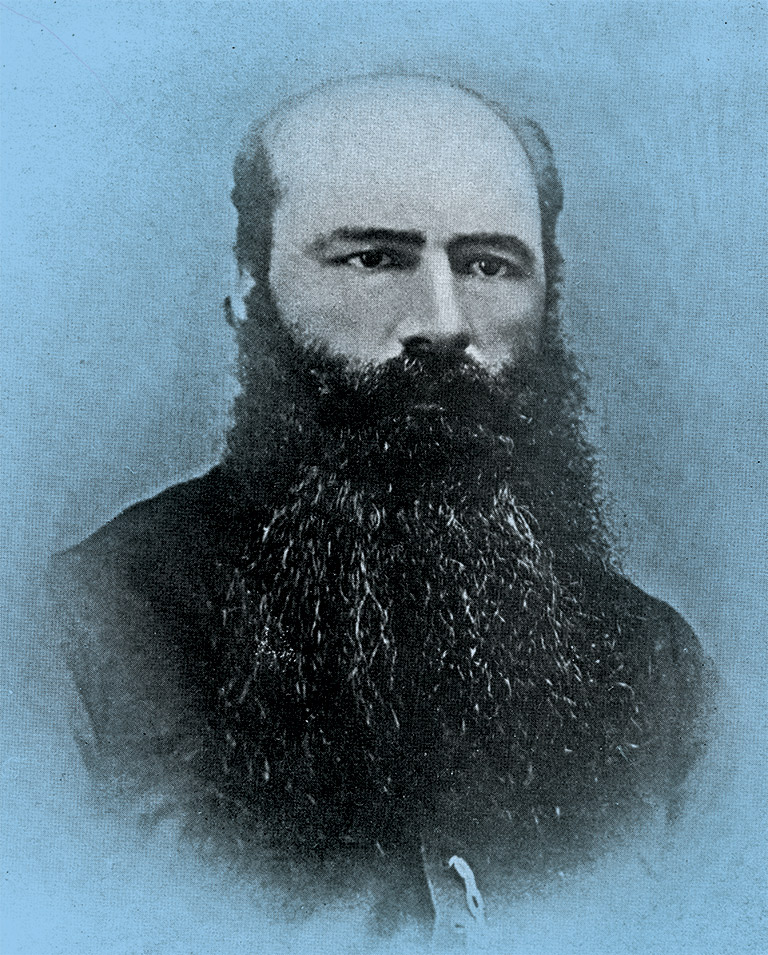

Born in L’Assomption, Lower Canada, in 1825, Ritchot had been appointed to St. Norbert shortly after his arrival at Red River in 1862. A burly man with an impressive beard, he remains a legendary figure among the Métis.

One story had it that a man arrived at a St. Norbert store looking to challenge the strongest man around. Ritchot lifted a hundred-pound (forty-five-kilogram) sack of flour onto the counter with one hand, which prompted the brawler to make a quick exit.

Ritchot saw the Métis as an isolated and embattled extension of French Canada; he shared their suspicion of les anglais and understood that their lifestyle, which he respected, was suited to their environment. The large Acadian community in L’Assomption, also wary of the English, may have helped to inspire Ritchot’s passionate desire to support the Métis.

That desire would place him squarely in the path of those who wanted to oppose Riel and to remake the Red River Settlement into a firmly English-speaking and Protestant community.

In the eyes of Riel’s enemies, the Métis leader and his followers were pawns in a “Popish plot” to thwart Ontario’s ambitions in the West. Ritchot and Red River’s diplomatic and conciliatory bishop, Alexandre-Antonin Taché, were cast as the true agitators behind the movement. In the eyes of the Canadian Party, the Catholic Church had too much influence and represented a local example of the menace they believed existed in Quebec.

A promising student, Riel had been sent east from the Red River Settlement at the age of fourteen in the hope that he would continue his education and come back as a Catholic priest.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Returning ten years later, in July 1868, Riel was young to assume a leadership position in a traditional Métis sense. He and his plans were bolstered by Ritchot’s support, and there is no evidence that Riel was in any way subservient to Ritchot, or especially to Taché.

Speculating that land claims made prior to the transfer of territory from the HBC would later be recognized by the Dominion, two leading members of the Dawson Road survey crew attempted to stake out lands just west of St. Norbert late in June 1869.

But John Snow and Charles Mair were chased off by Baptiste Tourond — who would later serve in several of the settlement’s legislative bodies — and others. The region southwest of the Forks was regarded as part of the Métis birthright via an entente nationale (a nation-to-nation agreement) with the English Métis.

From his St. Norbert pulpit at Sunday mass, Ritchot announced that Tourond had called for an assembly the next day. Notes on the early days of the resistance, which Ritchot prepared later, make it clear that the priest was in attendance and was more than a simple observer. He participated freely in this and other meetings unhindered by any interference from the absent bishop.

Indeed, Taché, anticipating difficulties in the settlement, had stopped in Ottawa while on his way to Rome to offer his influence as an intermediary.

He was brushed off by George-Étienne Cartier, the federal minister of militia and defence, but was later summoned home by the Canadian government in the hope that he could pacify his flock.

Father Georges Dugast summarized the opinions of the Métis — and of Ritchot — in a mid-August note to Taché. “How is it that, since we have not been sold as slaves, a foreign government has the right to come here to make us laws, to take possession of a country that belongs to us, without consulting us in any manner,” he wrote. “We will not refuse to become a part of the Confederation. But we are men and we will not enter like cattle.”

Anticipating that Canadian immigration to the area would pick up in the spring of 1870, Canada sent out John Stoughton Dennis and his survey crews in July 1869.

As Ritchot later informed Cartier, Dennis and his crew referred to each other with titles such as “colonel, major, captain; in the end to the final valet, they bestowed themselves with titles and airs of grandeur.” In his account, Ritchot also noted that, “excited solely by a young man of theirs” — namely, Riel — a small group decided that it had to act against “the injustice and the injury being made to the nation by Canada.”

And so, on October 11, 1869, Riel and others placed their feet on the survey chain of a Canadian crew and told them they had no right to work on lands claimed by the Métis.

The challenge quickly made Riel and his followers a force to be dealt with. Powerless before the ambitions of Canada, the local HBC authorities were equally ineffective in deterring Riel from advancing his program, first to prevent the assumption of Canadian authority and then to persuade the other settlers to support his efforts to negotiate entry into Confederation.

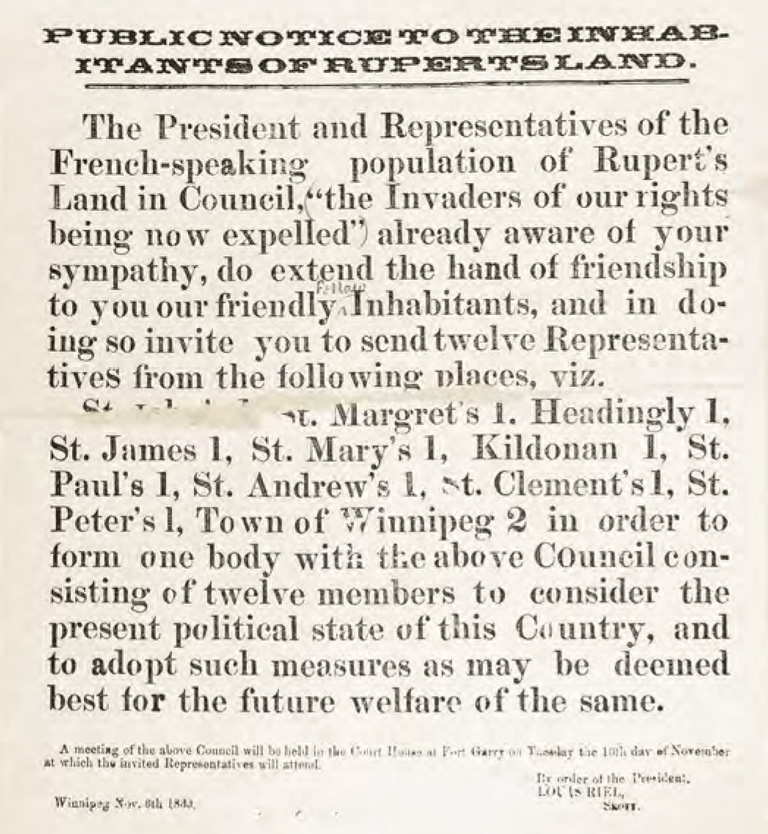

Riel intended that this would be achieved by organizing the settlement’s first democratically elected provisional government to administer the territory and to draw up a list of rights that would serve as a basis for discussion.

Not that there was much evidence of good faith on Ottawa’s part. Even before the execution of Thomas Scott, whom a military tribunal had found guilty of treason against Riel’s provisional government, Macdonald had taken steps to undermine Riel.

A participant in several counter-insurgencies in the settlement, Scott was a difficult prisoner who repeatedly threatened to shoot Riel and who even angered his fellow captives with his violent proposals.

The HBC’s Donald A. Smith, who would later become the company’s governor, was sent to Red River as a federal commissioner. He spoke of Canada’s good intentions and willingness to negotiate, all the while distributing Canadian funds to Riel’s enemies.

Failing in his secret mission — counter-coups by the Canadas had fizzled miserably — Smith executed his cover mission. In February, he extended the invitation for a delegation from Red River to go to Ottawa to negotiate an end to the crisis. The leader of the delegation would be Riel’s trusted confidant, Ritchot.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Although Fort Garry had replaced St. Norbert as the headquarters of the resistance, Ritchot had continued his involvement. On December 1, 1869, in the teeth of a howling blizzard, William McDougall ineffectively proclaimed the assumption of Canadian rule over the Northwest and his role as lieutenant-governor of the territory.

At the request of Riel, Ritchot and Dugast drafted a rebuttal that was printed on the press of the Nor’Wester, which the Métis had seized. The “Declaration of the People of Rupert’s Land and the North West” was signed by Riel as secretary of the provisional government and by John Bruce in one of his final acts as figurehead president.

In the last days of 1869, Dr. Charles Tupper (who later became prime minister) arrived in the region to recover his daughter, whose husband, Captain Donald R. Cameron, had been a member of McDougall’s presumptive administration.

On October 30, Cameron had arrived at La Barrière, the Métis stronghold in St. Norbert. The bridles of his horses were seized, and his wagon of household belongings was confiscated. He was then ordered to return to Pembina, south of the U.S. border.

When Tupper arrived in Fort Garry, he was sent to St. Norbert, where Cameron’s horses, carriage, and household goods arrived the next day. Tupper later wrote about telling Ritchot that the “rebels” could never hold the country and that, if bloodletting could be avoided, the leaders “would be entitled to great consideration.”

Ritchot’s response was apparently to say that the Métis could simply withdraw to the plains and fight indefinitely until aided by the Americans, perhaps suggesting that annexationists in St. Paul would be eager to join the fray.

The activist priest was also involved in discussions about whether the sentence of death would be carried out against Thomas Scott.

Taché’s successor, Bishop Adélard Langevin, later claimed that Ritchot had told Riel that he did not question the right to execute Scott but had endeavoured to dissuade him. (This assertion was countered by Riel’s brother Joseph, as well as in an affidavit sworn by André Nault and Elzéar Lagimodière the same year. The two men attested that Riel attempted to have the tribunal spare Scott’s life.)

For his part, Ritchot was said to have declared, “Make an example of him. If you do not execute this man, they will begin again.”

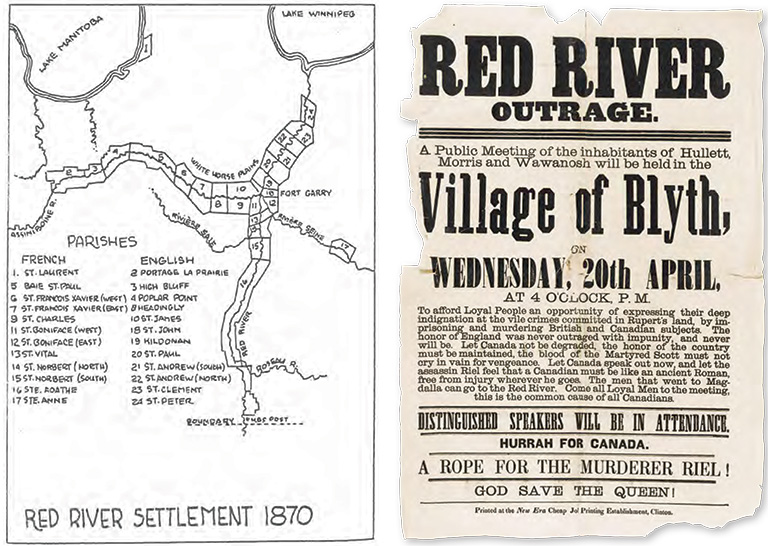

In the third week of March 1870, as authorized by the provisional government of Assiniboia, Ritchot, Judge John Black, and Alfred Scott left for Ottawa.

The chief law officer of the settlement, Black represented the English settlers. Scott, a bartender, represented the American element. With Ontario in an uproar over Thomas Scott’s execution, Ritchot and the saloon-keeper travelled via the United States to Ogdensburg, New York.

From there, for their safety, they were escorted to Ottawa by Gilbert McMicken, the Dominion police commissioner who was also Macdonald’s spy chief.

Ritchot and Scott arrived in Ottawa on April 12. They were soon joined by Black, who had no fear of travelling through Ontario. Prior to the start of negotiations, Scott and Ritchot were twice briefly arrested on warrants that had been privately sworn by Thomas Scott’s brother.

The arrests angered the British, who were informed that Canada had secretly paid the delegates’ defence costs. Ritchot used the time to hold informal discussions with Cartier, the militia minister and, later, acting prime minister during Macdonald’s extended illness, and with Secretary of State Joseph Howe and Governor General John Young, Baron Lisgar. Ritchot pushed to have the Red River delegation formally recognized as diplomats and for a start to the talks.

On April 25, the formal negotiations with Macdonald and Cartier finally began, in secret, in Cartier’s home. They concluded eight days later, with Macdonald later denying that they had happened.

When presenting the Manitoba Act in the House of Commons on May 2, he claimed, “we have discussed the proposed Constitution with such persons who have been in the North West as we have had an opportunity of meeting.” If Macdonald or Cartier took any notes from the talks, they have either been destroyed or their whereabouts are unknown.

Macdonald struggled with an almost impossible balancing act, one that may have led to a breakdown in his health. On one hand, he wanted to offer the absolute minimum required to settle and to have Britain approve his desired joint British-Canadian expedition to impose federal rule in Red River.

On the other hand there was growing tension between the Canada First movement, an Anglo-Protestant nationalist movement centred in Ontario whose members were agitating for Thomas Scott to be avenged, and Quebec Conservatives sympathetic to Riel and the Métis.

In a letter dated February 23, 1870, Macdonald wrote to a friend, “These impulsive half-breeds have got spoilt ... and must be kept down by a strong hand until they are swamped by the influx of settlers.” For their part, authorities in London had written to Macdonald on March 5, saying, “The proposed military assistance will be given if reasonable terms are given to the Roman Catholic Settlers....”

Ritchot maintained an “Ottawa Journal” that detailed both the discussions and his time in the capital. Stanley notes that reading between the lines of the diary reveals Black as being amenable to anything Canada proposed.

And, although it is seldom mentioned in Ritchot’s notes, others have suggested that Alfred Scott favoured the bar at the Russell Hotel over the negotiation table. Cartier and Ritchot dominated the discussions, and both apparently approached them with sincerity.

Ritchot quickly secured concessions that included immediate provincial status for Red River, the ability to maintain its bilingual institutions, protections for denominational schools, and financial arrangements that included per-capita grants as well as avoiding liability for Canada’s existing debts.

Significantly, Ritchot also received assurances that a general amnesty for all residents who participated in the resistance at Red River would be proclaimed before the arrival of any British or Canadian troops.

Days before receiving the suggestion from Riel that Assiniboia or Manitoba would be appropriate names for the new province, he inserted the word “Manitoba” in the blank space provided for the name of the new entity on a printed draft of the legislation.

The name comes from the Ojibway, who said Manito-bau, the voice of Manitou, the Great Spirit, could be heard at the narrows of the lake of the same name.

On the first day of the discussions, Ritchot had described the issuance of a general amnesty as a sine qua non of any agreement between Manitoba and Canada.

As he stated three years later in a petition to then Governor General Lord Dufferin, “The ordinary practice is not to invite rebels to treat, and negotiations are not entered into with the delegates if it is not proposed in case arrangements are effected, to pass the sponge over the past and proclaim a general amnesty for all acts anterior to the arrangements.”

Macdonald and Cartier declared that such an amnesty would have to emanate from the Crown and claimed that they could easily arrange to have one issued.

However, Ritchot’s efforts to document this commitment ended in failure, with Macdonald later denying ever having made the promise. The sincere if over-confident Cartier nonetheless provided Ritchot with an ambiguous statement that referred to a meeting he and Ritchot had had with Governor General Young.

At that meeting, they were supposedly told that “the liberal policy which the Government proposed to follow in relation to the persons for whom you are interesting yourself is correct, and is that which ought to be adopted.”

Although it had been written in his capacity as acting prime minister, Cartier’s later memorandum to London seeking the amnesty was undercut by Young, who also denied having made any such commitment.

The persistent lobbying of Ritchot, Taché, and others, as well as testimony by several witnesses before an 1874 parliamentary select committee, ultimately led Dufferin to grant conditional amnesty to Riel and to Ambroise D. Lépine — who had presided over the tribunal that decided Thomas Scott’s fate. Dufferin commuted Lépine’s death sentence on January 15, 1875.

On February 11 of that year Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie introduced a motion to Parliament granting full amnesty “to all persons concerned in the North-west troubles for all acts,” saving only Riel, Lépine, and W.B. O’Donoghue. Riel and Lépine were banished from “Her Majesty’s Dominions” for five years and lost their civil rights, such as the ability to vote and to run for office.

In contrast to the terms of the four original provinces’ entry into Confederation, the administration of all land in the new province was to remain under federal control. There were several reasons for this, which included meeting land arrangements with the HBC, dealing with the Indigenous populations, and providing for the planned railway.

After lengthy discussions, Ritchot believed he had secured compensation in the form of rights to existing landholdings, common pasturage and hay cutting, and an agreement that land would be available as grants for several generations of Métis children. All of this was to be administered by the provincial legislature.

The vagueness of the Manitoba Act on these issues as presented and passed by Parliament infuriated Ritchot, who, in the absence of Macdonald, lobbied Cartier for written confirmation of the oral agreements. According to George Stanley, “This obdurate priest was enough to drive a man to drink.” Macdonald had missed part of the formal discussions and nearly died during a subsequent attack of gallstones.

Cartier spent much of the month of May 1870 telling Ritchot that everything would be worked out in actual practice. As sincere as Cartier might have been, his death in 1872, combined with the maladministration by frequently unsympathetic federal agents of almost all things related to Métis land claims, led to years of frustration and confusion and was responsible in large part for the 1885 Northwest Rebellion.

A furious Ritchot wrote to Macdonald in 1881. He asked, rhetorically, “When the Hon. Ministers took so much pains to frame the clauses of the Manitoba Act, was it their intention, then, to add [a] few words to the phrases which would later, deprive the Manitoba settlers of their rights?”

In a memorandum dated May 23, 1870, which spoke of the amnesty without mentioning the word, Cartier also assured Ritchot that the administration of the 1.4 million acres set aside for the Métis would “be of a nature to meet the needs of the half-breed residents.”

One hundred and forty-three years later, when the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the Manitoba Métis indeed had legitimate grounds for their land claims, Cartier’s written assurances on land administration were held up by the court as expressing the “Honour of the Crown.”

In late June of 1870, Ritchot presented a lengthy report on his efforts. Based on his assurances that all would be well, despite the vagueness of the legislation, the approach of a military expedition, and the absence of an amnesty proclamation, he persuaded the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia to accept entry into Confederation.

Ritchot’s confidence was misplaced. Manitoba’s early years were marred by what became known as “the Reign of Terror,” during which many members of the Canadian military force abandoned any pretense of discipline in favour of individual and mob violence against perceived rebels.

Their actions included house burnings, beatings, murders, and “other outrages,” a euphemism for the rape of Métis women and girls. The propensity of the Canadian land agents to favour the claims of the newcomers over those of the original inhabitants only exacerbated the situation. The result was the diaspora of the Red River Métis.

Ritchot returned to Ottawa on several occasions to pressure for the promised amnesty, and he meanwhile endeavoured to maintain the French-Catholic identity of his parish.

When he was unable to persuade a Métis family to remain, he sometimes arranged to purchase the land or assumed the faltering claim with terms agreeable to the seller.

He would then sell the land on reasonable terms to incoming French-Canadian settlers. Any profits from land sales, loans, and mortgages were reinvested in the parish through schools, an expanded convent, an orphanage, and in the education of many of his parishioners.

Many Catholic clergy of the time, including Taché, are seen by the Métis as unsupportive or even as dupes of the Canadian government, but Ritchot was and is still held in high regard.

Riel wrote fondly of Ritchot while awaiting his execution. A prayer penned in Riel’s “Regina Journal” and dated August 15, 1885, asked that he be united even more intimately with the virtuous priest in order that they could form one heart and one soul that could work for the greater glory of God, the honour of religion, the triumph of truth and even the improvement of their enemies.

Over time, there has been an enormous change in how Riel and the events at the Red River Settlement are perceived. Even if the online comments sections for recent articles sympathetic to Riel remain troubling, the Métis and French Canadians are no longer isolated in their understanding of the events of 1869–70.

Manitoba declared in 2008 that the third Monday in February would be a holiday named Journée Louis Riel Day. “Keeping it Riel” T-shirts are hot items in gift shops, and the Esplanade Riel Pedestrian Bridge literally spans the divide between St. Boniface and downtown Winnipeg.

When Manitoba celebrates its sesquicentennial in 2020, Riel’s role as a father of its Confederation will no doubt be incorporated without serious question.

Whether the priest who was so central to negotiating Manitoba’s entry into Canada will be recognized is less certain. Aside from my own doctoral dissertation on the subject, Ritchot’s place in history has gone largely unrecognized and under-appreciated.

There are a few exceptions, however brief: Historian W.L. Morton wrote that it was “an unrecognized historical truth” that the people of Red River “would not have had half of what [they] had” if not for the priest from St. Norbert. And, in his still-definitive biography of Riel, Stanley wrote, “the combination of Ritchot and the younger Riel brought about the formation of Manitoba.”

A locally funded monument to both Riel and Ritchot stands next to the St. Norbert parish church, on what is likely the site of that first assembly held on July 5, 1869.

Although unidentified, the big, bearded Ritchot also makes a brief appearance in Historica Canada’s Heritage Minute about George-Étienne Cartier.

When one understands the crucial role of Abbé Noël-Joseph Ritchot in the events that shaped the creation of Manitoba, and when one realizes that interpretations of the Manitoba Act by modern courts reflect more of Ritchot than of Macdonald, consideration should perhaps be given to Ritchot as Manitoba’s other father of Confederation.

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!