Rage Against the Noose

Early in the morning of December 10, 1962, Arthur Lucas and Ronald Turpin still hoped they could avoid being marched to their deaths at midnight. Convicted of murder in separate cases, they were sentenced to hang at the Don Jail in Toronto. But there was reason to be optimistic. Prime Minister John Diefenbaker had commuted most court-imposed death sentences to life imprisonment, and the cabinet’s decision on a last-minute appeal was pending. Many in Toronto’s legal, academic, and religious communities were lobbying intensely for the government to step in to reverse the judgment of the courts.

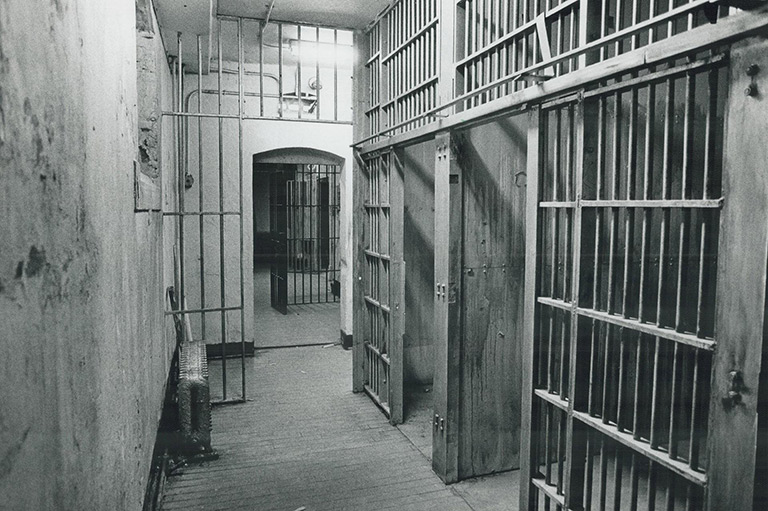

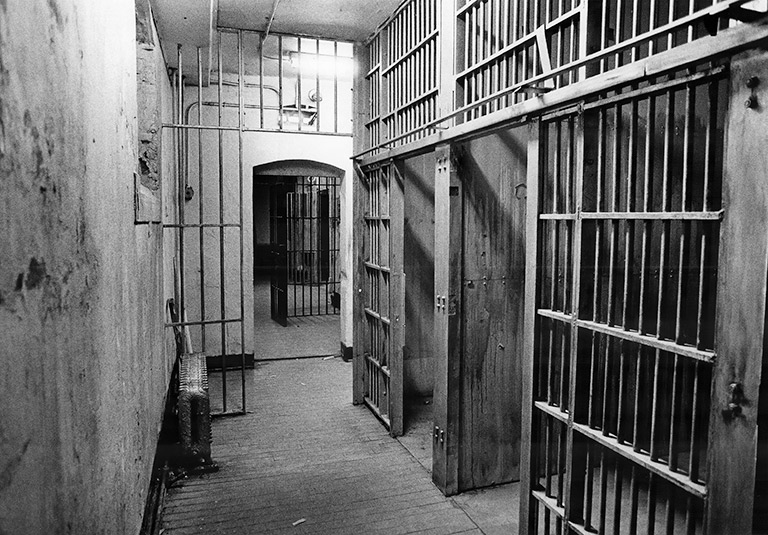

Shortly after noon, however, the news arrived: There would be no eleventh-hour reprieve. The government decided that the hangings would go ahead. Inside the century-old brick-and-stone jail on the east shore of the Don River, the two condemned inmates were reportedly calm in their final hours. Shortly before midnight, they were led to the small-converted washroom that housed the gallows. Two dozen men had been hanged in the same room over the years, ever since officials had moved executions indoors to prevent them from turning into public spectacles. With their hands bound behind their backs and manacles on their feet, wearing jail-issued blue pants and grey shirts, Lucas and Turpin stood back-to-back as the hangman slipped a noose over each of their hooded heads. At two minutes after midnight, the hangman sprang the wooden trap door. They were officially declared dead sixteen minutes later. Their bodies were driven across town to Prospect Cemetery, where they were buried side by side in unmarked graves.

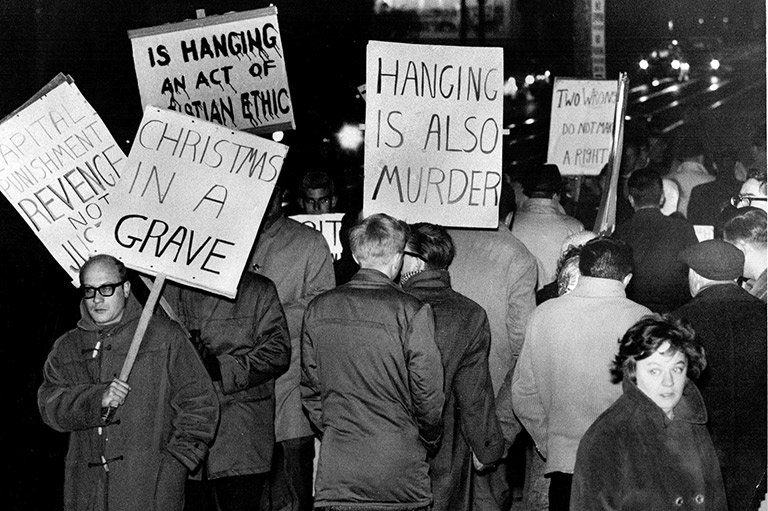

In the cutting wind and freezing temperature outside the jail, demonstrators had been picketing for hours. When jail officials posted a notice of the hangings at 12:30 a.m., the crowd surged forward shouting “murderers” and “killers.” Police had to call for motorcycle backup, and there were a few arrests before the crowd eventually dispersed. Meanwhile, members of the Don Heights Unitarian Congregation were holding a death-watch service in their church. “This ugly thing must be fought,” said Rev. Franklin Chidsey. “I refuse to accept the principle that there is anything such as a legal killing.”

The demonstrators couldn’t have known it, but the fifty-four-year-old Lucas and twenty-nine-year-old Turpin would be the last people executed in Canada.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Capital punishment has a long history in Canada. It was meted out in colonial times for dozens of offences, but by 1865 it was reserved for murder, rape, and treason. Between 1867 and 1962, Canada executed 710 people, always by hanging. But the practice was controversial, and the first formal effort to eliminate it came in 1914 when Member of Parliament Robert Bickerdike proposed an ultimately unsuccessful private member’s bill. Venezuela was the first country to abolish the death penalty for all crimes in 1863, but only a handful of others followed in the next hundred years.

The debate over capital punishment in Canada was particularly intense in the 1950s and 1960s, and some high-profile death sentences fuelled it. Two days before the scheduled hangings of Lucas and Turpin, law professor John Desmond Morton was set to give a talk on CBC Radio on the subject. He was a well-known opponent of the death penalty. On short notice, the public broadcaster cancelled the show and rescheduled it for after the executions, saying that it “would not be in good taste” and “would serve no useful purpose.” Morton was outraged. “It is nonsense to say that to discuss the case beforehand would not be in good taste. Hanging is not in good taste.”

Many opponents of capital punishment cited religious or moral grounds for their arguments. Morton himself said nothing in Lucas’s or Turpin’s records prompted his stand, “except that they are human beings.” Most of the people who supported the death penalty, on the other hand, talked about its deterrence value. In an editorial the day after the hangings, the Toronto Star mocked that rationale. It pointed to police efforts to keep the crowd as far away from the Don Jail as possible.

“If there is anything to the deterrence theory, the proper time and place for an execution would be at noon in front of the city hall, with a brass band in attendance, so that as many people as possible would be encouraged to see the uplifting spectacle.” The Star was blunt in its conclusion: “A hanging such as last night’s is simply a barbaric and degrading survival from the past. Everyone involved is ashamed of it and wants, instinctively, to conceal it from public view.”

But whatever one’s moral standards or convictions, and no matter what evidence one believed about the deterrence factor, there was another powerful argument for abolishing the death penalty. What if the convicted person was innocent of the crime? A wrongful conviction might be discovered years later, but if the accused had already been executed there would be no correcting the injustice. Between 1956 and 1966, four Canadian journalists — two women and two men — played a central role in driving this point home to the Canadian public. Their investigative work cast doubt on the criminal convictions of three people who had all been sentenced to hang. In so doing, they laid the groundwork for the eventual elimination of capital punishment in Canada.

Soon after the Don Jail executions, Globe and Mail reporter Betty Lee began to take an interest in precisely what had happened. Both Lucas and Turpin had been charged, tried, and convicted with lightning speed. Turpin’s case seemed straightforward. On February 12, 1962, he stole more than six hundred dollars from the Red Rooster restaurant in Toronto and fled the scene in his battered truck. Soon afterwards, he was pulled over by Toronto Police Constable Frederick John Nash. The details of what happened next are foggy, but at the end of a gunfight between the two Turpin was injured and Nash lay dead. Turpin never denied his involvement in the crime.

It was an entirely different story when it came to Lucas. A resident of Detroit, he was accused of driving to Toronto on November 16, 1961, with the express purpose of killing fellow American Therland Crater in a rooming house. Both were involved in organized crime, and the prosecution argued Lucas was intent on killing Crater so that he wouldn’t testify against a third Detroit crime figure in an upcoming trial. Crater was allegedly co-operating with authorities.

Australian-born Lee was a hard-nosed journalist who instructed everyone to call her by her last name. A high school dropout at sixteen, she started off writing scripts at a radio station. She then moved to London, England, where she worked briefly at a tabloid before heading to Canada and a job at the Globe and Mail. Her former managing editor, Clark Davey, remembered her as a fierce and talented reporter. “She was one of the early practitioners of long-form journalism, a magazine writer hiding out in a daily newspaper,” Davey once told the Globe and Mail. “She would dominate a room just by walking into it, with her physicality and a very loud voice.” Lee approached her investigation the way few reporters of the day did. She read the trial transcripts from cover to cover, interviewed all the relevant players, and came up with an independent analysis of the evidence used to send Lucas to his death. It resulted in a controversial, multi-part series in October and November of 1963. At the end of her investigation, a Globe and Mail editorial concluded that “she has produced enough disturbing facts to cast serious doubts on the quality of Canadian justice as it concerned Arthur Lucas.”

Lee pointed out that the case against Lucas was entirely circumstantial. No one had seen him at or near the place of the murder. He had always proclaimed his innocence, even in his final moments, and that view was shared by his lawyers, academics who studied the case, and the chaplain who comforted him in his last months at the Don Jail. Among the compelling questions Lee posed, which she felt were never adequately answered, were: Why would Lucas check into a hotel room under his real name and address if he was on a mission to murder someone? Why did he call the future victim twice from his hotel room, knowing that authorities could easily check the hotel switchboard calls? When he dropped by to see Crater, a man he knew and had visited previously, why would he make a traceable collect call back to his home in Detroit if murder and secrecy were on his mind? Lee also noted that the same rookie defence lawyer was assigned to both Lucas and Turpin and had the difficult task of conducting both trials three weeks apart. The lawyer got seven hundred dollars in legal-aid funding for two and half months of preparation, while lawyers estimated that the Crown spent as much as forty thousand dollars on the prosecution.

Reading the transcript of the judge’s final address to the jury, Lee noted that the accused’s defence took up twenty-eight lines. The Crown’s case, meanwhile, was detailed over fifty-five pages. In the end, the all-white jury found Lucas, a Black man, guilty in five hours. There was no recommendation of mercy.

Advertisement

Around the same time that the public was digesting Lee’s revelations, Quebec journalist and future senator Jacques Hébert released a book that also exposed problems in the prosecution and execution of a man accused of murder. The title left nothing to the imagination: J’accuse les assassins de Coffin. The English translation, titled I Accuse the Assassins of Coffin, added the subtitle: American tourists murdered, an innocent man hanged. It built on earlier research and books that both Hébert and Toronto Star reporter J.E. Belliveau had written concerning the dubious murder conviction of Wilbert Coffin in 1954 and his hanging two years later.

The journalistic investigation began in July 1953 when Belliveau, known as Ned to his fellow reporters, went into the Star newsroom to pick up mail. An eight-year veteran at the newspaper, he had left school at seventeen to take his first journalism job with the Moncton Transcript. Then it was on to the Windsor Star, and finally to the competitive Toronto newspaper market. Harry Hindmarsh, the newspaper’s national editor, approached Belliveau to tell him that three Americans had been mauled by bears in Quebec’s Gaspé region. Would he head to the area immediately to cover the story? The Star sent him and two other reporters, along with a photographer, expecting a sensational string of stories.

When the journalists got there, even before provincial police officers from Quebec City had arrived on the scene, they discovered an even more gruesome story. The hunters had apparently been shot to death, their bodies found separately in the bush. It turned out that Eugene Lindsey, his seventeen-year-old son, Richard, and twenty-year-old Frederick Claar had left Pennsylvania on a bear-hunting trip on June 8, expecting to be gone for two weeks. Searchers went looking for them when they still weren’t home a month later. That’s when police made the disturbing discoveries.

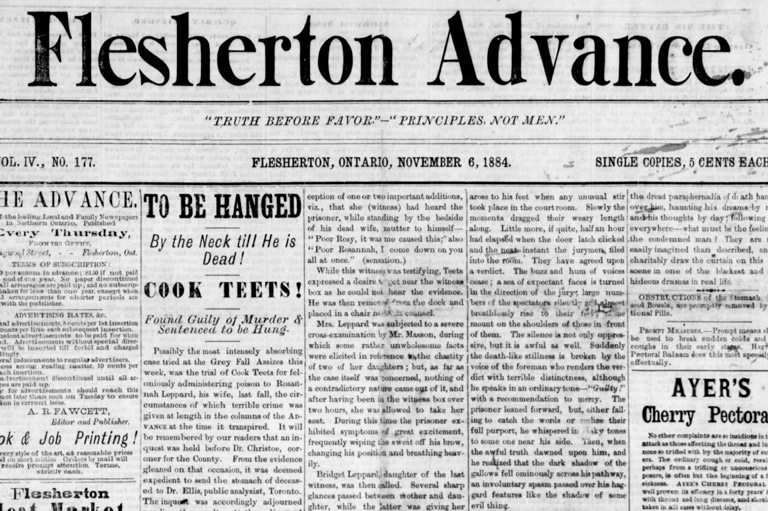

Suspicion quickly fell on Wilbert Coffin, a thirty-seven-year-old mining prospector who lived in the area and was the last person believed to have seen the men alive. He had helped them fetch a spare part when their truck broke down. When objects belonging to the victims were found in Coffin’s vehicle, he was arrested and charged with murdering one of the hunters, Richard Lindsey. He was in custody for nearly a year until his trial in July 1954.

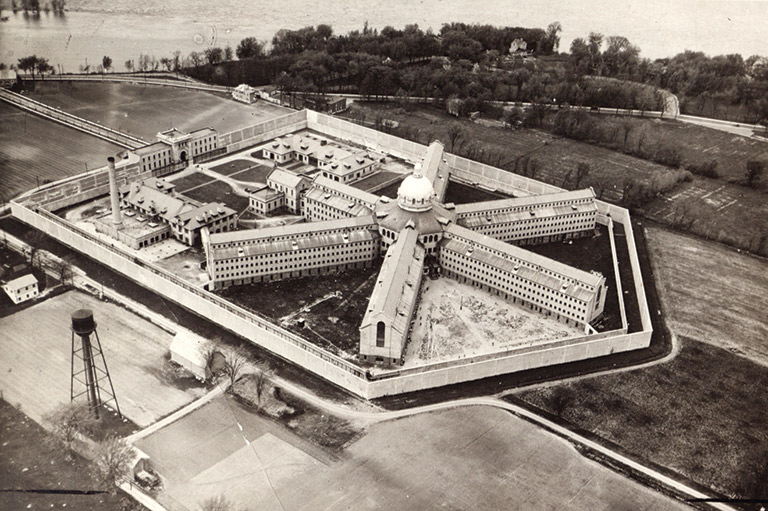

The Quebec government spared no expense in its investigation and prosecution. The trial lasted nineteen days, but the jury took just thirty-four minutes to convict Coffin, and the presiding judge sentenced him to hang. Despite appeals all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada and a series of reprieves, he was finally executed in Montreal’s Bordeaux Prison on February 10, 1956.

Belliveau understood the complexities of the case better than anyone, having covered its twists and turns from the very beginning. Within months of the execution, he published a book called The Coffin Murder Case. As Betty Lee would do years later, Belliveau dissected the case for the prosecution and found many problems. Police never found a murder weapon, and the deterioration of the bodies made it hard to establish an actual cause of death. There were no direct witnesses, and police never found a convincing motive. Coffin’s lawyer, the police officer who arrested him, the prison chaplain, and even his hangman believed that the man with no prior criminal record was innocent.

Belliveau also questioned why the police never took fingerprints from liquor bottles found at the scene or bothered to figure out who owned the mysterious jeep seen near the murder site. It was a landmark book, the first in Canadian history by a journalist who openly criticized a suspected wrongful conviction. “If a man can be hanged on the basis of circumstantial evidence, from which is missing that final link which determines beyond all reasonable doubt that he fired the shot to kill the victim of his violence, the question arises whether any one of us is safe,” he wrote.

Belliveau’s book caused waves in English Canada, but it wasn’t until the muckraking journalist Hébert began covering the case that interest in Quebec grew. Hébert had worked as a reporter at Le Devoir, and in 1954 he launched Vrai, a weekly newspaper that took aim at the regime of Quebec Premier Maurice Duplessis. He also started his own publishing house and joined Cité Libre magazine. Hébert seized every opportunity to critique Duplessis, and the Coffin affair provided a big one. His first book, Coffin était innocent, left no doubt about where he stood on the facts of the case. He accused the Duplessis government of caving in to pressure from the U.S. State Department to solve the murders, suggesting that pressure was intense to protect the province’s tourism industry. The book sold forty thousand copies, but he said he wasn’t surprised that Duplessis ignored it. Hébert wouldn’t let go of the case, and in late 1963 he published his most daring exposé yet, entitled J’accuse les assassins de Coffin.

Hébert contended that Duplessis pressed everyone in the justice system to convict Coffin because Washington was pressuring him to do the same. He said he travelled forty thousand kilometres “checking the slightest clues, finding new witnesses, and questioning over a hundred persons” all over North America. While Belliveau had boasted that he “kept to careful reporting and avoided flamboyant commentary and judgment,” in his book Hébert took the opposite tack. In addition to exposing contradictory evidence, he accused the police and Crown of wilfully suppressing facts because they were bent on getting Coffin convicted. “The slightest trail that led to any other suspect but Coffin was systematically covered up,” he wrote. “Their aim was to use any means at their disposal to destroy such evidence.” The case’s high profile was undisputed, and some of the players were rewarded after the trial. Two of the senior police officers were promoted, the chief prosecutor entered politics and became a federal cabinet minister in Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s government, and his assistant joined the Supreme Court of Quebec. But for Hébert they were assassins of an innocent man.

With uncanny prescience, Hébert ended his book with a call to the provincial government: “Unless you can prove that I have lied and throw me in jail for public mischief, your duty is clear. You must appoint a Royal Commission of Inquiry without delay.”

The Quebec government did just as Hébert had demanded and convened a Royal Commission, but it was evident that justice officials were not about to find fault with their brethren. The inquiry upheld the Coffin conviction and spent most of its time criticizing the role of lawyers and the media. Commission chair Justice Roger Brossard said the Coffin controversy would only stop “if people stop writing books about the case.” But justice officials were studious readers of Hébert’s book, and they also complied with his second demand: throwing him in jail. The government charged him with contempt, and a judge sentenced him to thirty days in jail and a three-thousand- dollar fine. He spent just three days behind bars before his friend, lawyer, and travelling companion, future prime minister Pierre Trudeau, sprung him out and filed an appeal. The appeal court overturned the conviction a year later.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

While doubts around the executions of Coffin and Lucas continued to swirl, a fourth journalist was hard at work trying to show how yet another person had been wrongly convicted and sentenced to hang. The critical difference in this case, however, was that Steven Truscott was still very much alive and could be freed if facts could show there had been a miscarriage of justice.

Truscott’s case is perhaps the best-known example of a wrongful conviction in Canada, with key events in the saga spanning nearly half a century. In 1959, when he was fourteen, he was charged with murdering twelve-year-old classmate Lynne Harper in Clinton, Ontario. All the elements of a potential wrongful conviction were present: purely circumstantial evidence, questionable scientific testimony, conflicting witness statements, and critical evidence withheld from the defence. In September 1959, Truscott was convicted and sentenced to hang. The federal government commuted the sentence to life imprisonment, and he exhausted all further appeals.

The idea that a fourteen-year-old could be sentenced to hang shocked Canadians, and it disturbed Isabel LeBourdais, who had a son the same age. At fifty, LeBourdais was a freelance writer, publicist, and social activist. She marched in demonstrations for nuclear disarmament and peace, was pro-choice, and supported the civil rights struggles of Black people. She was also staunchly opposed to capital punishment and advocated for the rights of mental-health patients. She began looking into the Truscott case, not knowing what she would find but convinced that a fourteen-year-old did not deserve to be executed or to spend his life in prison. In a masterful example of investigative journalism, she met with lawyers and jurors in the case, pored over the trial transcripts, interviewed experts, and weighed all the Crown’s evidence. She became convinced that Truscott was innocent. “Every witness, every clue, every fact that did not support a case against him was overlooked or ignored from the hour the body of Lynne Harper was found,” she wrote.

Her biggest struggle was not marshalling the evidence but getting the results published. Faith in the justice system was still strong among the Canadian establishment, and publishers were reluctant to target police and courts in the strident way LeBourdais was proposing. As the controversy over Hébert’s book was playing out, publisher McClelland and Stewart sent LeBourdais’s manuscript to a team of lawyers for evaluation. They wanted a considerably watered-down version. LeBourdais balked, refusing to accept more changes. She eventually convinced a British publisher to put out the book. Ironically, McClelland and Stewart became the Canadian partner in distributing it when the book, The Trial of Steven Truscott, finally hit the stands in 1966.

The book was a sensation, selling more than sixty thousand copies in short order and convincing politicians to ask the Supreme Court to review the case. Despite LeBourdais’s impressive work, the court didn’t overturn the original conviction. Few people knew at the time that significant evidence was being suppressed. The prosecution’s case relied on testimony from the autopsy doctor that the time of death fell within a window that implicated Truscott. But he re-evaluated his analysis and admitted that the time of death might have been later, when Truscott could not possibly have been involved. That re-evaluation was never shown to the defence or to the court.

It wasn’t until 2007 that the Ontario Court of Appeal finally quashed Truscott’s conviction and acquitted him. The following year he received $6.5 million in compensation. Truscott credited LeBourdais for playing a critical role in reviving interest in his case and uncovering facts pointing to his innocence.

The book by LeBourdais appeared just as the House of Commons had its first substantive debate on capital punishment in March and April of 1966. Every Member of Parliament had been sent a copy by this point. A motion to abolish capital punishment was hotly debated and eventually defeated by a vote of 143 to 112. The following year, a bill was passed imposing a five-year moratorium on the death penalty, except when it involved murders of police or corrections officers. After five years the ban was extended, and Parliament finally voted in 1976 to remove the death penalty from the Criminal Code. Certain military offences still carried the death penalty until 1999, when those sentences were also eliminated. It’s clear from the timing and impact of their work that J.E. Belliveau, Jacques Hébert, Betty Lee, and Isabel LeBourdais each played a critical role in convincing Canada to join the list of countries that refused to sanction state-supported killing.

Advertisement

Steven Truscott was ultimately vindicated in court, but, incredibly, the cases of Arthur Lucas and Wilbert Coffin remain the subject of doubt more than sixty years later. Serious questions about their convictions and eventual executions are unanswered. Win Wahrer, director of client services for Innocence Canada, said a team of investigators began re-examining the Lucas case in 2007. They accumulated numerous documents and tried to locate decades-old evidence. “We worked on it for years,” she said. “We believe he is innocent.” But Wahrer said the trail went cold, and the file is now on its inactive list. It doesn’t mean they have given up, and Innocence Canada has a track record of helping to free twenty-four innocent people since 1993.

The Coffin file, on the other hand, remains an active one for the organization. Wahrer said they are still hopeful that the federal government will finally review the case. “We owe it to the family,” she said. Marie Coffin-Stewart, Wilbert Coffin’s sister, remains convinced that her brother was innocent. She remembers him as a kind person who loved hunting, fishing, and cooking. At ninety-one, she is the second-youngest of eleven children and one of only two surviving siblings. She is a significant supporter of Innocence Canada and has contributed to its efforts on behalf of her brother. “I promised I would raise $10,000,” she said from her home in Ottawa. “And I raised $10,200. A lot of baking, bake sales, and bingos. I knitted a blanket for a double bed and sold that. I picked blueberries and sold them.” Coffin-Stewart believes the Canadian justice system is unfair. “All these people still get thrown into prison who didn’t do it. The justice system of Canada sucks. There’s something radically wrong with it.”

THE JOURNALISTS WHO FOUGHT THE DEATH PENALTY

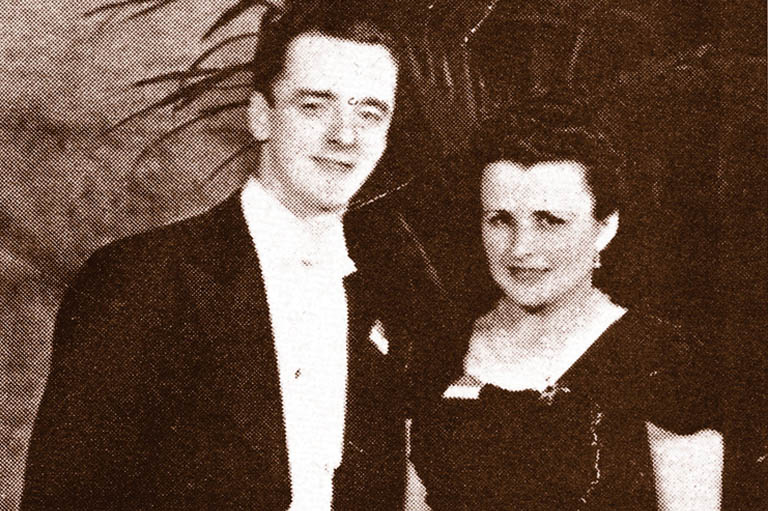

Betty Lee dug into the cases of Arthur Lucas, who was hanged for murder along with Ronald Turpin on December 11, 1962. Thanks in part to her reporting, they were the last two people executed in Canada. An investigative reporter ahead of her time, she died in Toronto in 2015 at the age of ninety-three.

Jacques Hébert exposed the corruption behind the conviction of Wilbert Coffin. After a long career in journalism he was appointed to the Canadian Senate in 1983 by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. He died in 2007 in Montreal at the age of eighty-four.

J.E. Belliveau was a reporter who covered the Coffin case. His exposé of the apparent wrongful conviction stirred public sentiment against the death penalty. He died in 1998 in Moncton, N.B., aged eighty-four.

Isabel LeBourdais was a writer and activist whose book The Trial of Steven Truscott exposed the conviction of the fourteen-year-old boy as a miscarriage of justice. After a lifetime of criticizing the justice system, she died in 2003 in Toronto aged ninety-three.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement