Playing Ball with Castro

In August 1964, fourteen Canadian teenagers assembled in Montreal to train for the upcoming World Junior Baseball Championship in Cuba. Hand-picked by Montreal baseball bigwig Marcel Racine after a competitive tryout camp, these nine Quebecers, two Manitobans, two Albertans, and one Nova Scotian formed Canada’s first national junior baseball club, chosen to represent the maple leaf in the baseball-mad Caribbean country.

Initially, Cuba’s baseball federation announced the World Junior Baseball Championship as a twelve-team competition, intended to cultivate goodwill toward the island nation that had been isolated since 1962 by a U.S. trade embargo. But in the months before the competition, other countries’ teams began to drop out. The number of confirmed competitors dwindled to eight, and then to just six. Defying the American embargo, the Canadian team stuck by its commitment to play in the tournament.

On September 4, Racine and his players boarded a plane to Nassau, Bahamas, then transferred to a Soviet airliner bound for José Martí International Airport in Havana, Cuba. As the flight approached the Cuban coast, the players saw American naval vessels patrolling the waters to enforce the embargo. “I didn’t have binoculars or anything, but you could read the words [in English] on the sides of the ships,” said Bob Davisson, then a sixteen-year-old left-handed pitcher from tiny Oakbank, Manitoba.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

When they landed in Havana, the Canadian team learned that Aruba, Chile, Argentina, and Mexico had all pulled out of the tournament at the last minute. Collectively, their vaguely articulated reasons boiled down to pressure from the United States. In the end, Canada would be playing Cuba exclusively in a five-game series. These fourteen young men, aged sixteen to nineteen, would be the first athletes from a Western country to compete in Cuba since the embargo had been imposed.

“I’m sixteen years old. I don’t really understand what’s going on in the world,” recalled Mike Ortuso, a shortstop from Montreal’s Saint-Henri neighbourhood. “I was just so happy to go and play baseball.”

Tensions between the United States and Cuba could hardly have been higher in 1964. Cuba’s revolutionary leader Fidel Castro had assumed power in 1959, and by 1960 he had explicitly embraced Communism, expropriating large landholders, signing a trade pact with the Soviet Union, and publicly denouncing the United States. The Americans severed diplomatic ties with Havana in January 1961, and in April U.S.-armed Cuban exiles failed to recapture the island in the notorious Bay of Pigs invasion.

In October 1962, the discovery of Soviet missiles in Cuba led to a crisis that put the Russians and Americans on the brink of nuclear confrontation. Between 1960 and 1965, American agents made several attempts on Castro’s life. Meanwhile, on November 22, 1963, U.S. President John F. Kennedy was shot dead. The man accused of his murder, Lee Harvey Oswald, was an avowed Communist who campaigned publicly for a pro-Castro organization, leading many Americans to believe that the Cuban government had played a role in the president’s assassination.

Canada took a middle path on Cuba, neither fully backing the regime, as did the Soviet Union, nor pushing for its demise, like the Americans. John Diefenbaker, prime minister of Canada from 1957 to 1963, pushed successfully for continued trade with Cuba and normalized diplomatic relations with Havana. These policies, continued by Diefenbaker’s successors, proved a source of tension between Ottawa and Washington for decades. President after president griped about Canada’s stance, but the Americans proved unwilling to push too hard against their top trading partner.

In March 1964, Marcel Racine learned of Cuba’s plans to host an international youth baseball tournament. A Montreal-based mover and shaker, Racine served as a regional scout for several Major League Baseball teams and was the president of the Canadian Federation of Amateur Baseball, which evolved into Baseball Canada. He knew that Cuba was the gold standard in global baseball, holding the number one ranking internationally after beating out the United States for the championship at the 1963 Pan American Games.

Despite Cuba’s baseball pedigree, Racine also knew that the island country needed the participation of pro-American Western democracies to make the tournament a diplomatic government for his team’s participation, as well as complimentary transportation plus room and board for his team during its visit. The money allowed the cash-strapped Canadian contingent’s excursion to Cuba.

Advertisement

In preparation for what was supposed to be a twelve-team tournament, the Canadians hosted a junior Cuban team for a goodwill series in Montreal and in Sorel, Quebec, in August. The Canadians squeaked out a 3–2 win in that five-game series. But when they arrived in Havana in September they confronted a much different opponent. This Cuban junior team included just two of the players who had come to Canada — the others were clearly a more physically mature bunch. “They were older. They all shaved and had heavy growth. At that time, I don’t think I saw a razor on my face,” the left-handed pitcher Davisson said.

“They were a class above us,” Ortuso agreed. “They played with such intelligence. Even practising before the game, you could see they were well-trained.”

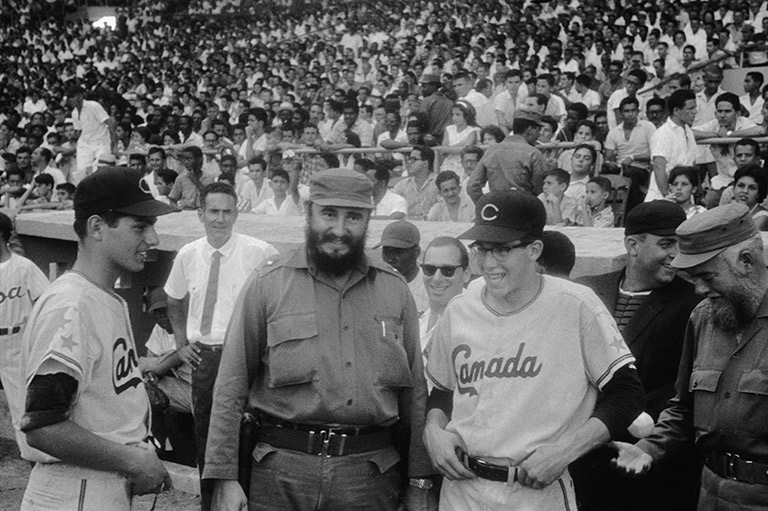

The seriousness with which Cubans took the series was evident immediately. Twenty-seven thousand fans filled Estadio Latinoamericano in Havana to watch the opening ceremony and the first game. Surrounded by a military entourage, Castro threw out the ceremonial first pitch and greeted the Canadian team warmly. Cuban sharpshooters took up positions throughout the stadium to ensure the leader’s safety. The series was broadcast on state television and radio across Cuba, while more than one hundred thousand fans attended the five games.

“The biggest crowd I played in front of before I got to Montreal was maybe sixty or seventy people,” said Davisson, who pitched for the rural municipality of Springfield in Manitoba’s junior baseball league. In Havana, he faced a stadium full of fans who stomped, clapped, and cheered at just the right moments to break an opposing pitcher’s concentration.

A further impediment to the Canadian players was the heat. The day of the opener, the temperature hit forty degrees Celsius. Subsequent games were played at night when temperatures remained at thirty degrees or higher. The Canadians took salt pills to prevent dehydration. It was a far cry from the August exhibition series in Montreal, when Cuban players had complained about the chilly twenty-degree days and fifteen-degree nights.

Still, Quebec reporter Jean Aucoin, who travelled with the team to report on the series for the Montreal newspaper Le Petit Journal, wrote that the Canadians were welcomed like kings. “On the first day of the tournament, the Estadio Latinoamericano opened its doors at 10 a.m.

“Two hours before the match, the stands were already nearly full to capacity, while outside people were lining up at the ticket counters. The first match was played in front of 28,000 people.

In game one, the Canadians took a 1–0 lead in the top of the first inning before eventually succumbing to Cuba’s offensive clout. The home team won 11–2. In the second game, Canada’s Gilles Wilscam battled Cuba’s Alberto Reyes in a masterful pitching duel that Cuba won 2–0. Canada broke through with a 9–8 extra-inning win in game three — a marathon battle that lasted five hours before ending at 1:20 in the morning. Cuba defeated Canada 9–6 and 5–1 in games four and five, securing a 4–1 victory in the series.

The top Canadian hitter that week was Ortuso, who batted .333 and received a trophy from tournament organizers recognizing his outstanding performance. “That one is precious to me,” Ortuso said of the trophy he still cherishes six decades later. “I won many in my baseball and hockey career, but you don’t get one from Cuba every day.”

The moment the Canadian players made their entrance into the stadium, the crowd erupted into applause. And when the players were officially introduced, it was literally complete delirium.

The most memorable game of the Canadian junior team’s visit took place after the formal series. Fidel Castro, known for his love of baseball, pitched and played right field in an exhibition game during which the Canadian and Cuban players were split into mixed teams. No fans attended the exhibition at Estadio Latinoamericano, and Castro was surrounded by bodyguards at all times when he was not on the field.

Castro’s team won 10–1, a typical score in such staged games. Baserunners were told not to steal bases against the Cuban leader. Canadian pitchers were told to pitch slowly to Castro, enabling him to hit the ball into play.

Castro hit a grounder to third off Davisson, which Davisson’s third baseman, a Cuban, muffed on purpose, allowing the leader to get on base. On September 10, a headline in the Winnipeg Free Press read, “Fidel Castro got a hit off Bob Davisson.” Jim Rutherford, a pitcher from Alberta, told the Calgary Herald that Castro was “no great shakes” as a pitcher, explaining that the Cuban leader threw a curve that didn’t curve and a fastball with little speed on it. “He’d look bad in our junior league,” Rutherford told the Herald.

One Canadian player — catcher Michel Bergeron — proved irksome to Castro on the leader’s otherwise glorious afternoon. Small in stature but long on guts and smarts, Bergeron grew up in the Rosemont neighbourhood of Montreal. He later gained fame as “le Tigre,” the fiery coach of the NHL’s Quebec Nordiques and New York Rangers during the 1980s. “He was a firecracker,” Davisson said. “Michel was the go-getter who’d get you pumped up.”

During one of Castro’s at-bats, Bergeron signalled for fireballing pitcher Don MacGowan to throw two hard strikes, then a slow one, to let Castro hit it. Once Castro got to third base, the Cuban revolutionary took a long lead off the bag. The next batter missed the first pitch, and, after catching the ball, Bergeron stepped in front of the plate and pump-faked a throw to third. Castro dove headfirst back into the bag. When he got up, his body and beard were filled with chalk and dirt. Bergeron earned a long, hard stare from Castro.

In another notable play, Bergeron tagged Castro out firmly at home plate, a definite no-no when playing against the Cuban leader. The stories of Bergeron getting under Castro’s skin provided colourful anecdotes in many profiles of the defiant, confrontational coach as his Quebec Nordiques challenged the rival Montreal Canadiens for provincial bragging rights during the 1980s.

After the exhibition game, Racine offered Castro a brand new baseball glove, but he refused the gift. “Fidel wouldn’t accept it. He said, ‘this is too nice. My people don’t have something this nice. I don’t have it either,’” Davisson said. “Coach [Racine] looked over his shoulder and saw me and said: ‘Give me your jacket.’” Castro accepted Davisson’s well-worn Team Canada jacket.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Between games, the players saw several sides of life in Cuba. They stayed on the top floor of the Hotel Habana Libre, spending significant amounts of time by the pool and making the acquaintance of many young Cuban women. They toured cigarette and cigar factories, and a group of them once went horseback riding through the countryside. They interacted frequently with locals and formed genuine friendships with some of the people they encountered. Ortuso and Davisson both maintained correspondence for years with friends they’d made in Cuba. “The people were extremely nice,” Ortuso said. “They were really happy to see people from other countries. They were very gentle.”

The players heard about the ration books Cubans used for everyday purchases. After games, crowds of children gathered around them, asking for Chiclets gum. The players got a more intimate sense of the privation Cubans faced at the end of their visit.

“They allowed their team to come up to our rooms at the hotel as we were leaving,” Davisson said. “The players bought all of my clothes. Blue jeans just weren’t available. I hardly had anything to bring back.”

Davisson has visited Cuba many times since the 1964 series, attempting on several occasions to meet Castro and to retrieve his jacket. He has made many friends, toured Estadio Latinoamericano, and given out a great deal of baseball equipment to the children he’s met. When he told people in Cuba that he’d played in the series, they encouraged him to wear the medal he’d received from Cuban officials. In his twelve visits to the island, it has proven to be a great conversation starter on many occasions.

Appearances in Cuba by baseball teams from North America were few and far between for the next twenty years. International baseball tournaments featuring Canadian teams and, occasionally, American teams came to the island on a couple of occasions in the 1970s and 1980s. An exhibition game between Major League Baseball’s Baltimore Orioles and the Cuban national team at Estadio Latinoamericano in 1999 began a thaw that remains incomplete to this day.

As recently as March 2023, an appearance by Team Cuba at the World Baseball Classic in Miami caused a tremendous stir in the Florida city famous for its large community of Cuban exiles.

The group of Canadian teenagers that travelled to Cuba in 1964 took advantage of a unique opportunity to compete against some of the best players in the world. At the same time, they represented the best of their country, particularly its willingness to carve a distinct path internationally, even if these young men and their enterprising coach didn’t realize it at the time.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement