Men Against the Desert

Dawn Cline was twelve years old when the Second World War broke out. Her father, a United Church minister, joined up as a chaplain, heading overseas alongside many young soldiers from her hometown of Highgate, Ontario. She did what she could for the war effort, including selling war savings stamps and writing letters to young men who were serving overseas. Mature beyond her years and a local beauty, she exchanged letters with many servicemen; but one Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) pilot in particular was a frequent correspondent. That pilot, Robert Leslie Spence, would turn out to be a celebrated airman whose exploits saw him immortalized as a comic-book hero.

Born in Highgate, Spence was a twenty-one-year-old farmer and an “old chum” of Cline’s when he enlisted on October 8, 1940. His letters to Cline were full of banter and witty responses to her news from home. “We have high hopes of being moved from here in 2 weeks or less,” wrote Spence in 1940 from RCAF Station Rockcliffe in Ottawa, a site of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. “Please don’t mention anything about the flu being in the camp just in case it gets to my mother.” Regarding his transport to England in 1941, he wrote, “I always wanted to take a trip on an ocean liner but not under the circumstances that I took it in. Now I’m here and all I’ve got to do is worry about the boat ride back. … I sure was glad to get your letter even if it did chase me all over the east coast of Canada and over most of England to catch me.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Sometimes Spence’s sentences were laced with the vernacular of that era: “Flying sure is swell and there are no ditches up there,” he wrote in one letter. On October 6, 1942, Spence’s return address was “the Middle East.” He wrote about the lack of rain, having a cold from riding around in the back of a truck, and the scarcity of official letter cards to write on. He ended the note by saying: “Keep your chin up and I’ll be seeing you.”

The very next night, Flight Sergeant Spence and his crew took off from Royal Air Force (RAF) Station Kabrit in Egypt with seven other Wellington bombers in order to hit targets in Tobruk, Libya. The mission was part of the North Africa campaigns, which lasted from 1940 to 1943 and pitted Britain and France, with their colonial and British Commonwealth forces, against Germany, Italy, and Italy’s African colonies. The stakes were high: imperial dominance in Africa, control of the Suez Canal, and access to the valuable oil reserves of the Middle East. British and Australian troops had captured the coastal fort of Tobruk from the Italians in January 1941; but Axis forces under German General Erwin Rommel had captured it back in June 1942.

During his mission to Tobruk, Spence’s plane was hit by flak, and the port engine caught fire and seized. He ordered his crew to abandon the aircraft. Two crew members — the observer, RCAF Flight Sergeant Cameron Clare Hill from Kitchener, Ontario, and the second pilot, RAF Sergeant Kenneth Bowhill from London, England — fell into enemy hands and were taken prisoner.

The four remaining crew members — Spence, RAF air gunner Sergeant Arthur Butteriss, RAF tail gunner Sergeant Eric Linforth, and Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) gunner Sergeant John Wood — rendezvoused at the crash site near Fort Capuzzo, Libya. The bombed-out former Italian stronghold lay deep in enemy territory, more than 480 kilometres from the closest British positions at El Alamein, Egypt. Collecting their emergency rations — including tins of bully beef, sixteen packs of hardtack, some bottles full of water, milk tablets, chocolates, and toffees — the foursome set out with Spence in charge. They headed southeast into the desert and then turned east to continue walking parallel to the coast.

The heat was scorching during the day, and Wood wore a remnant of a parachute on his head as protection against the blazing sun. Their wool-lined flying boots were unbearably hot, and the desert rocks wore through the soles; at one point they cut new insoles from the rubber found in a military wreck.

Advertisement

After four days they crossed into Egypt. But the two RAF gunners, Butteriss and Linforth, had injured their ankles in the jump from the burning plane. Seven days into their journey, Butteriss could go no further. He elected to be left behind, awaiting capture by enemy forces. Two days later, Linforth was also forced to give up the trek. Both of them were captured as prisoners of war. Meanwhile, Spence and Wood continued onward.

Fifteen days after the plane crash, the two men reached the Qattara Depression, an eighteen-thousand-square-kilometre, below-sea-level basin in northwestern Egypt, filled with treacherous salt marshes, dry lakes, and windblown sand dunes. Impassible to military vehicles because of its steep embankments and precarious quicksand, the depression could be crossed on foot. It also formed a natural barrier between the British forces to the east and the Axis forces to the west. For Spence and Wood, reaching the depression meant they were getting close to the British defence lines at El Alamein.

But they were also running out of food and water. By the end of the nineteenth day, their rations were gone, and they had only two full bottles of water between them. Fortunately, they met Bedouins who gave them small amounts of rice, camel milk, and water. They also found water at some wrecks in the desert. There was only one brief rain shower during their entire journey. It wasn’t enough to fill their bottles, but it did allow them to drink out of a rock pool. Despite needing all their energy to survive, Spence and Wood managed to cut some enemy communication lines, rewiring them incorrectly in order to throw off Rommel’s army.

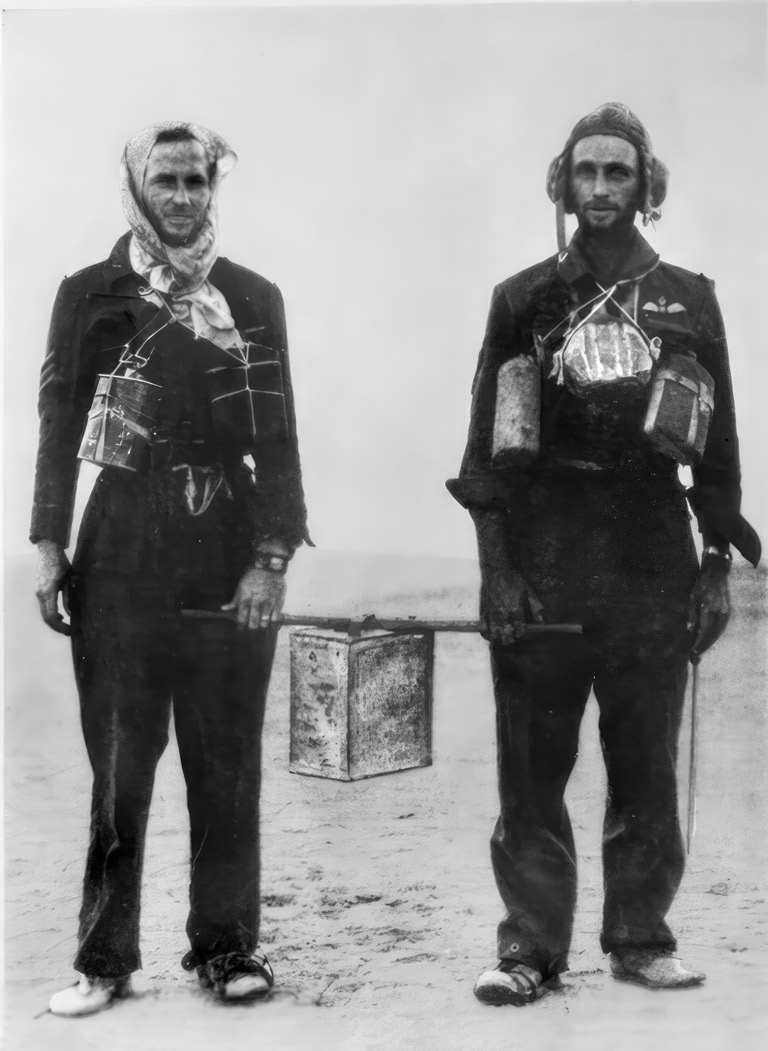

On November 2, after a 560-kilometre trek, the two airmen were discovered by a British advance armoured division north of El Maghra, Egypt, and taken to safety. They were immediately given a meal and a drink, but Spence and Wood refused to wash or to change until they were flown to their squadron. Once there, they were placed in sick quarters in order to have proper baths and beds.

Meanwhile, fearing that he was dead, or perhaps alive and burnt beyond recognition, Spence’s family in Highgate waited for news. After nearly a month of agonizing uncertainty, they were informed that he had survived.

On November 24 Spence wrote to Dawn Cline: “I suppose you have heard all about my little walk by now. Yes, yes, honey chile it was some hike – about 350 - 400 miles [560 to 640 kilometres] in 23 days of open road. I have a wizard photograph of myself just after the end of our jaunt. It’s pretty good. I’ll send you one. … Right now I’m in a hospital and I don’t really know what for…. The trouble with this hospital stuff is I got put here while on leave and everyone knows that’s bad even you (poor thing). And besides that I am missing all the fun back in the Squadron. … No, I didn’t want to go for a hike. I’ve had enough hiking to last me for some time, a couple of days at least!”

After their hospital stay, Spence and Wood spent one week’s leave in Palestine, receiving VIP treatment from everyone they met. Both men wanted to quit flying, but they decided that they had better continue, or they would never have the nerve to do it again. They returned to combat duty, flying out of Malta. Spence would have liked to have stayed in the Tunisian campaign, but the RCAF had other plans. The two airmen were about to play a key role in the Allied war propaganda machine.

In May 1943, Spence and Wood were flown to Canada, with a stop along the way in London, England, for Spence to receive a Distinguished Flying Medal from King George VI. They both also received the coveted Flying Boot, a badge worn by RAF aircrew who walked back to safety after being forced to abandon their planes.

Canadian publicity began with an RCAF press release on May 22, 1943, that described the two men’s cross-desert trek and announced that they were back in Canada. On May 24, the Montreal Gazette reported on a press conference where the airmen described their exploits. On May 25, the Windsor Star announced the arrival of Spence and Wood in Thamesville, Ontario, by train at 12:45 p.m. And what an arrival it was.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

“It’s not much like the day he left. There was no band out [then],” commented Spence’s mother, Rhoda Spence, in the Windsor Star on May 26. “It was pouring rain when he got on the train in Chatham. I never could have imagined anything like this.” Mayors, reeves, magistrates, police chiefs, Boy Scouts, legionnaires, musical bands, veterans, and other townsfolk celebrated the airmen’s triumphant return. Even schoolchildren were given the day off. The sound was deafening as people screamed and cheered while fire engines and cars blew their horns. Spence and Wood were overwhelmed. “We’re like a couple of bloomin’ conquerin’ heroes!” said the amazed Wood, as they were swarmed by adoring Canadians. The victory parade travelled sixteen kilometres to Ridgetown, Ontario, and followed another ten-kilometre route to Highgate, where it finally ended at the front door of the Spence home.

Later in life, Cline recalled the excitement of that day. Since she was a friend of the family, she was chosen to present Spence with a bouquet when he got off the train. She was also featured in publicity photos taken at the Spence home. By then she was sixteen but looked a few years older, making her the perfect local sweetheart figure in staged group photos.

After their leave in Highgate in 1943, Spence and Wood travelled to New York City for broadcasts and appearances, before touring Canadian industrial cities. It may have been in New York where their story came to the attention of the Parents’ Institute, an American organization that published an educational comic-book series called True Comics.

Abiding by its slogan, “Truth is stranger and a thousand times more interesting than fiction,” True Comics aimed to counteract the superhero comics that the Parents’ Institute saw as detrimental to the education and morality of youth. With an advisory board that included pollster George Gallup, True Comics produced eighty-four issues between 1941 and 1950.

Advertisement

In February 1944, True Comics published Spence and Wood’s story in a strip entitled “Men against the Desert.” Although the storyline stayed true to reality, the writers indulged in some poetic licence with the dialogue. After bailing out of the plane in the middle of the night, the character representing Wood comments: “Spence, it’s as dark as Hitler’s heart down here!” Later, while draining water from the radiator of a wrecked German Jeep, he remarks: “Awfully nice of the Jerries to leave this soda fountain for us, wasn’t it?”

By appearing in True Comics, Spence and Wood joined British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, explorers Samuel de Champlain and Sir John Franklin, First World War flying ace Billy Bishop, American frontiersman Daniel Boone, U.S. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, and Chinese military leader Chiang Kai-shek, to name but a few of the featured historical figures.

Despite Spence’s humorous tone in press releases and in his letters to Cline, he later confided to her that he had recurring nightmares about the whole ordeal. In particular, he harboured a tremendous sense of guilt about leaving his injured crew mates, Butteriss and Linforth, behind.

On September 23, 1943, Spence was reported to be in a state of extreme anxiety as a result of the relentless pace of his overseas duty and Canadian publicity tours. On November 5, a member of the National War Finance Committee wrote to Allied Force Headquarters praising Spence’s contributions to the Fifth Victory Loan campaign: “I know that Bob has not been very keen on public appearances but on the other hand he has at all times been extremely courteous in acceding to requests to speak at meetings. He has spoken at all hours of the day and night, from 7:30 a.m. one day until midnight another. He has at all times carried himself in such a manner as to be a very definite credit to the RCAF. We appreciate very greatly your courtesy in allowing him to help us, and hope that his experiences have not been too painful for him.”

Remarkably, all of the crew members of Spence’s downed Wellington survived the war. Hill, Bowhill, Butteriss, and Linforth remained prisoners in Axis POW camps. Wood, who had trained as a gunner in Winnipeg and in Dafoe, Saskatchewan, prior to the crash in the desert, stayed in Canada to train as a pilot. The Australian War Memorial counts among its artifacts the fuse case that Spence and Wood used to ration water and the piece of parachute worn by Wood as a sun protector. Bob Spence became a flight instructor in Dunnville, Ontario, and remained friends with his wartime pen pal and “old chum” Dawn Cline. He married June Jewitt and had two daughters, Linda and Rhonda, and three grandchildren. He died in 1995 at age seventy-six and was buried in Ridgetown.

Dawn Cline married Dr. John Trueman and co-authored award-winning history textbooks while raising six children. She passed away from frontal-lobe dementia in 2016, although memories of her wartime correspondences with Spence and other Canadian servicemen remained intact until the end.

Comic Connection

Discovering my family’s link to a war hero.

As a child, I pored over my collection of historical comic books. When I became a teacher, I discovered that the world of comics turned even the most ambivalent students into enthusiastic historians. Imagine my astonishment when I discovered that I had a personal connection with an RCAF pilot turned comic-book hero! A yellowed, musty-smelling comic became one of my most prized possessions and a link to my family’s past.

Seventy-six years after the end of the Second World War, I was teaching an elementary-school class about Canadian history, and we were creating comic books. While researching historical comic strips to use as examples, I came across a 1944 comic entitled “Men against the Desert.” On closer examination, I realized that the characters in this thriller were none other than Canadian pilot Robert Spence and Australian gunner John Wood, who had been shot down over enemy territory in Libya and trekked for more than five hundred kilometres to freedom. I recognized them because I’d seen photos that my mother, Dawn Cline, had taken of the two young men in uniforms, grinning at the camera after their return to Canada.

I immediately ordered the comic book, and one week later it appeared in my mailbox. Leafing through my treasured online purchase, there were a few things that struck me. The incredible storyline didn’t deviate from Spence and Wood’s recounting of their tale in newspapers of the day; no embellishments were needed to create these Commonwealth heroes. Given the sense of humour he showed in the letters to my mother and in his convivial dealings with the press, I think Spence would have been amused by the illustrations. He and Wood were depicted as chisel-jawed, muscular figures with superhero physiques. Despite the hokeyness of the comic strip, my students were thoroughly engaged in the story and the illustrations, and they read “Men against the Desert” several times — even after I assigned it as homework. — Dawn Martens

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement