The Lives of the Lachine Canal

The St. Lawrence and Ottawa rivers converge at the western tip of the Island of Montreal, and there, the St. Lawrence widens, forming Lake St-Louis. Then, suddenly to the southeast, the waterway narrows and drops precipitously. Vast quantities of water are funnelled through this channel and propelled over shallows, boulders and small rocky outcrops, falling 13 metres over three kilometres. Known as Ohnawa in the Mohawk language (kanien’keha:ka), these are the rapids that awed French explorer Jacques Cartier when he first encountered them in October 1535. As he noted in his journal: “At that point there is the most violent rapid it is possible to see, which we were unable to pass.”

Navigation upstream remained impossible for almost 300 years, until the opening of the Lachine Canal in 1825. Since then, the canal has evolved and changed while remaining an important feature of Montreal life. To mark the canal’s 200th anniversary, here’s an exploration of some of its many lives.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

From dreams of China to dreams of a canal

Christened the Sault St-Louis by Samuel de Champlain early in the 17th century, these rapids were a formidable obstacle to navigation and endowed the unknown landscape beyond with mysterious possibilities. What lay upriver? Could this be the doorway to China, the long-sought route to the Orient and its wealth? Such was the conviction of Rene-Robert Cavelier de La Salle when he set out from Ville-Marie in July 1669 with a group of companions and a flotilla of canoes heading up the St. Lawrence. A year later, the men returned empty-handed and were mocked as the “Chinois” by their neighbours; a settlement on the nearby shores of Lake St-Louis, on land owned by La Salle, came to be known as “La Chine.”

Throughout the French regime, the Lachine rapids remained an insurmountable barrier to continuous navigation on the St. Lawrence. Their presence contributed to the development of Montreal as the westernmost harbour for ocean-going vessels and a transshipment hub. To reach the interior of the continent, French explorers, missionaries, fur traders and soldiers were forced to first travel overland, from the colonial town of Ville-Marie to the hamlet of Lachine, a journey of roughly 11 kilometres. The Sulpician seigneurs of the Island of Montreal were quick to recognize that a canal would be an effective means of facilitating the movement of goods and travellers upriver. Work began in 1689 but was soon interrupted — and then abandoned entirely — because of conflicts between the French and the Haudenosaunee as well as escalating costs.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

In the decades following the Conquest of New France and the American Revolution, settlement along the St. Lawrence in Upper Canada increased and the impetus for improving navigation upriver from Montreal grew. Talk of canals filled the air, but the cost and technical challenges of such an undertaking were daunting. In 1805, as a stopgap measure, colonial authorities attempted to open a channel through the rapids, but this venture met with limited success. The War of 1812 and its aftermath created a favourable context for canal building, but not on the Island of Montreal.

Discouraged by the inertia of the imperial authorities and fearful of the economic impact of the Erie Canal, whose construction had just begun, a group of Montreal merchants decided to take matters into their own hands. In 1819, they formed the Company of Proprietors of the Lachine Canal and began the arduous task of raising capital for their vision. This private venture failed miserably and, in 1821, the Legislature of Lower Canada, with the financial support of London, appointed commissioners to supervise what had now become a public undertaking. The ceremonial groundbreaking took place in Lachine on July 17, 1821, and work then advanced slowly until the final segment of the canal was completed in 1825.

Building and rebuilding a canal

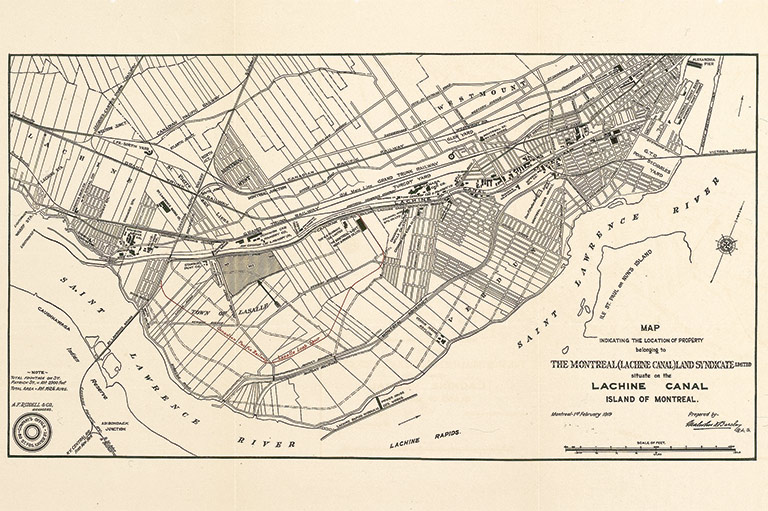

The late 18th and early 19th centuries were the golden age of canal building. When construction began in earnest on the Lachine Canal, Canadian authorities had access to the expertise of engineers well versed in canal design and the challenges of regulating the flow of water. Each canal, however, was unique due to the characteristics of its associated body of water and the landscape it had to traverse. The Lachine Canal posed specific challenges due to its 15.5-kilometre trajectory, 13-metre descent between its upper entrance at Lachine and junction with the port of Montreal, in addition to being a route over long stretches of solid rock and swamp.

The path and the specifications of a canal — its width and depth, as well as the number and the size of its locks — were a response to the physical environment, but they were also determined by the needs of contemporary shipping and available financing. Inevitably, as commerce evolved and grew, the transportation requirements of trade changed as well, as did the capacity and characteristics of ships involved in inland navigation. As a result, every canal risked becoming inadequate or, worse, obsolete. But their capacity could not easily be enlarged or improved. The only real solution was creative destruction — the progressive and systematic demolition of portions of the existing structure followed by additional excavation and new construction. This was the fate of the Lachine Canal: open to navigation in 1825, substantially rebuilt in the 1840s and again 30 years later.

The first Lachine Canal was conceived in the age of the sail, when inland navigation in North America relied on the bateau and the Durham boat, both relatively small vessels with flat bottoms. To accommodate them, the initial canal was 15 metres wide and 1.5 metres deep, with seven locks measuring six metres by 30 metres. A towpath along the north side facilitated the movement of boats. By the late 1830s, the dimensions of the canal were deemed inadequate. With funding from the imperial government and under the supervision of the Board of Works of the Province of Canada, the Lachine Canal was enlarged to accommodate steamboats and vessels plying the Great Lakes. Its depth was almost doubled, to 2.75 metres, and the locks were modified to increase their dimensions while reducing their number.

Advertisement

The 1870s and early 1880s saw an even more ambitious reconstruction project. The canal’s depth was again increased, this time to 4.25 metres, and pairs of locks replaced the single locks to reduce congestion. During these years, the canal was widened and deepened, and the area between the St. Gabriel locks and the Port of Montreal was reconfigured to increase the capacity for transshipment and warehousing and to more fully integrate the easternmost portion of the canal with the harbour. As a result, ocean-going vessels could now enter the canal to take on and deliver cargo. By the late 19th century, the Lachine Canal had reached its full extent, with many characteristics that still persist.

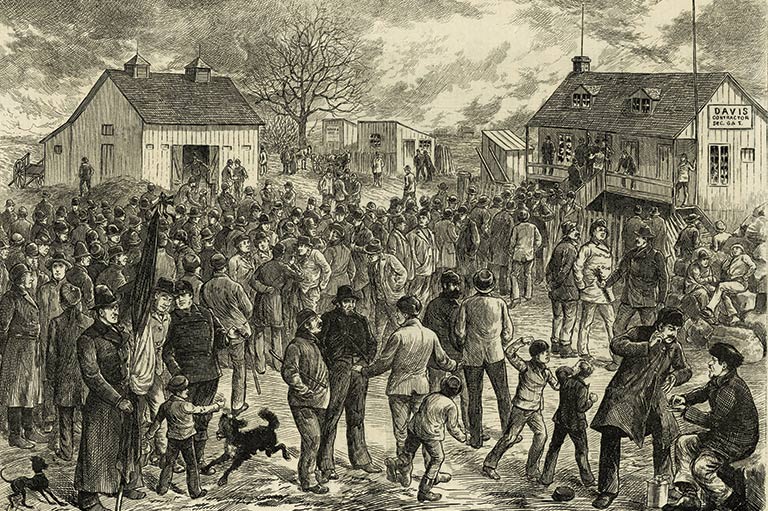

Constructing, enlarging and improving the canal was a monumental labour-intensive undertaking. Although some of the back-breaking work was eliminated by the introduction of steam shovels in the 1870s, these could only be used in certain areas. For the most part, canal-building continued to rely on hard, physical labour with picks, shovels and wheelbarrows, supported by carters with their horses and wagons. More specialized tasks required carpenters and stonemasons.

The bulk of the labour force was made up of migrant labourers, for the most part Irish immigrants. They were hired by the canal contractors and lived in shanties near the work site, sometimes with their families. Their working and living conditions were dismal; they endured long hours and meagre pay, often unscrupulous overseers and a harsh environment. Those enlarging the canal in the 1840s and 1870s worked through the winter months, when navigation was interrupted, the canal drained and segment after segment could be rebuilt. Winter was a time of seasonal unemployment in Montreal, and contractors took advantage of the situation to reduce wages and exert pressure on their workers. It’s not surprising that violent strikes erupted in 1843, worsened by conflicts between the Irish from Connaught and from Cork, and that canal labourers again walked off the job in 1877 — this time with the support of Montreal’s nascent labour movement and Joe Beef, the colourful proprietor of a tavern near the canal.

The heart of industrial Montreal

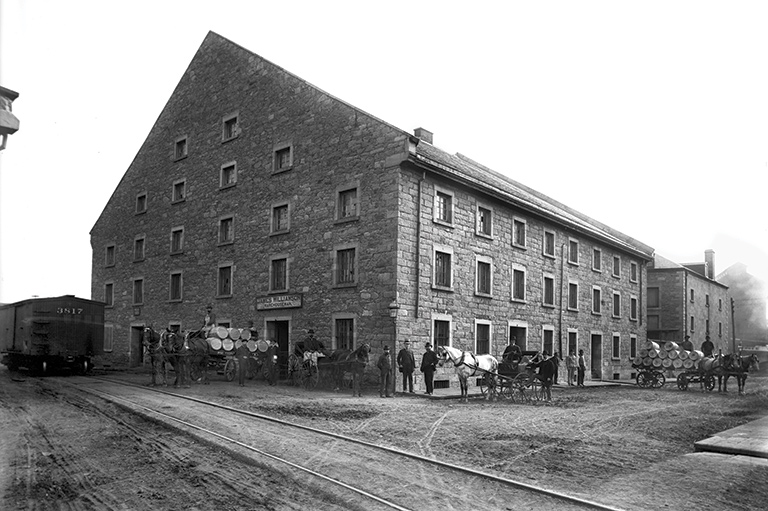

The building of the Lachine Canal was promoted by merchants, forwarders and shipping companies because the improved flow of goods between Montreal and Upper Canada and points west was vital to their economic interests. The canal was designed to be a commercial highway — and it achieved that goal. The number of ships and the volume and value of merchandise passing through it increased in a spectacular fashion from the 1820s to the 1950s.

But the canal wasn’t simply a thoroughfare; it was a transportation and transshipment hub, a crucial link in transcontinental and international logistics and supply chains. The lower segment, known as the Montreal terminus, was the heart of this hub; there, numerous basins, wharves and warehouses were frequented by canallers, lake freighters and ocean-going cargo ships unloading or loading lumber, coal, wheat and other grains, as well as a range of manufactured goods and raw materials from foreign lands.

However, the canal was destined to become more than a chapter in the history of Canadian transportation and commerce. The topography that had required the construction of numerous locks to manage the descent from Lachine to Montreal was not just an obstacle to be overcome. The change in elevation at each lock, and especially at the Montreal locks, also meant that the energy of the displaced water could be harnessed to generate power. By the 1840s, turbine technology was already being used elsewhere to drive industrial machinery, and many Montreal merchants and early industrialists recognized the canal’s potential. When it was rebuilt in those years, channels similar to mill races were incorporated at each of the locks to feed new hydraulic lots set out and leased for factories. Within a few years, grist mills, foundries and a host of metalworking factories were built on the aptly named Mill Street, along the basin above the two Montreal locks.

Additional hydraulic lots were soon leased and developed upstream, near the St. Gabriel locks, followed a few years later with similar developments at the Cote St. Paul locks. Hydraulic power was an early impetus to industrialization, but the canal’s attraction persisted even when steam, and then electricity, became the dominant source of energy. It came to be known as Montreal’s “Smokey Valley.”

By the early 20th century, the whole of the Lachine Canal corridor was lined with hundreds of factories. It was a veritable who’s who of Canadian business: the Grand Trunk/Canadian National Railway, Ogilvie Flour Mills, Redpath Sugar, Dominion Textile, The Steel Company of Canada, Northern Electric, Dominion Bridge, Sherwin-Williams, Imperial Tobacco — and the list goes on.

Canal working-class life

The first Lachine Canal was essentially a rural waterway, crossing fields and farmland between the village of Lachine and Montreal, then a small colonial town of approximately 25,000 people. The arrival of industry along its banks, beginning at its lower entrance at the Port of Montreal and spreading beyond the city limits, changed this landscape. New working-class neighbourhoods and industrial suburbs emerged on both sides of the waterway, stretching from Montreal to Lachine. Their growth was stimulated by an insatiable demand for workers — men, women and children — and by large-scale immigration from the British Isles and Europe, as well as the migration of French Canadians from the countryside. These powered Montreal’s growth to almost 700,000 residents by 1921.

The canal’s neighbourhoods near Montreal were varied, influenced by their factories, ethnic and religious composition, and the shared history of the inhabitants. Griffintown was a predominantly Irish enclave, born in the pre-industrial city and shaped by its proximity to both the port and the canal. It was one of Montreal’s earliest manufacturing districts.

Pointe-St-Charles had a different trajectory. Located south of the canal, it was farmland until the 1840s, divided into properties owned by various religious orders. Its emergence as an industrial and working-class neighbourhood was the result of the hydraulic industrialization along the canal as well as the opening of the Grand Trunk Railway shops in the 1850s. It was perhaps the most diverse of the canal’s industrial districts, with large French-Canadian, Irish-Catholic and Anglo-Protestant populations and a labour force composed of highly skilled craftsmen, less-skilled factory hands and general labourers. Residential patterns within “the Point” reflected those fault lines.

A third important working-class community along the canal, St-Henri, was different. Located about halfway between Lachine and Montreal, it began in the late 18th century as a craft village. Its original population was French Canadian, and developments near the St. Gabriel locks in the mid-1850s attracted newcomers from the countryside around Montreal. As the population grew, the village became a town, and then a city later annexed by Montreal. Its elected officials worked aggressively — and successfully — to attract new industry. By 1901, the population of the three communities exceeded 50,000.

In many respects, whether you worked and lived in Griffintown, Pointe-St-Charles or St-Henri, daily life was similar. There were the schedules and routines of the factory, the struggles to pay the rent and feed one’s family. There were moments of exceptional working-class solidarity, especially during and after the Second World War, when hard-fought strikes brought significant improvements in wages and working conditions to many. There was the fellowship and support found in parish life, and the strong bonds of family. There was a rich popular culture. The texture of life in those neighbourhoods in the mid-20th century can perhaps best be understood through novels like Gabrielle Roy’s Bonheur d’occasion (translated as The Tin Flute), documentary films like A Saint-Henri le cinq septembre and the wealth of photographs preserved by archives, museums and local history societies.

A sea change

On June 26, 1959, Queen Elizabeth 11, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Canadian Prime Minister John G. Diefenbaker inaugurated the St. Lawrence Seaway. This massive binational infrastructure, begun in 1954, was 3,700 kilometres long and enabled ocean vessels to travel unimpeded up the St. Lawrence, past the Lachine and other rapids, through the Great Lakes to Lake Superior. At that moment, the Lachine Canal was made obsolete. It served a limited number of local businesses for a few years, but its days as a major maritime highway were over. Between 1966 and 1970, the basins and locks immediately upstream from the Port of Montreal were backfilled, and in 1970, the canal was officially closed to navigation.

What was now to be done with the canal? Was it to be backfilled in its entirety and the space devoted to other purposes? By the mid-1970s, a new vision focused on improving urban life, revitalizing industrial and port areas and reconnecting with nature began to take shape — fuelled by broader social movements in Montreal and elsewhere. In the summer of 1975, a pilot project opened 1.6 kilometres of the canal’s towpath to cyclists; two years later, the bike path was extended to the canal’s full length. This was a crucial first step in the development of the Lachine Canal as a recreational and tourism destination, under the management of Parks Canada.

In the early 1990s, Parks Canada’s mandate for the canal was broadened and its work intensified. All along the canal, factories were closing down or moving elsewhere and, paradoxically, their disappearance led to a growing awareness of the exceptional industrial heritage of the Lachine Canal. In 1997, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board recognized its importance by creating the Lachine Canal Manufacturing Complex National Historic Site of Canada.

Over the next five years, Parks Canada restored the canal and its numerous features, including excavating its lower entrance at the harbour. In 2002, the Lachine Canal was reopened to navigation for pleasure craft. During the same period, Parks Canada’s historians and archaeologists worked to document the canal’s history and preserve elements of its heritage, in spite of the ongoing demolition and the conversion of former factories into lofts and condominiums.

As the Lachine Canal celebrates its 200th anniversary, it seems the waterway has entered a new phase in its long life. Yet, even in its commercial and industrial heyday, it was often appreciated as a place of leisure and contemplation. Back in October 1826, Montreal apothecary Romuald Trudeau described in his journal a walk along the “canal de la Chine” as being the most pleasant that Montreal had to offer.

Visitors today would no doubt agree.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement