Saving Skid Row

Just before March 20, 1933, an explosion rocked Vancouver’s East Hastings Street, blasting a small crater in the entrance to Pantages theatre. The blast also shattered every window of the nine-storey Balmoral Hotel across the street. Miraculously, no one was killed. Police blamed it on labour unrest.

The theatre had just hosted a meeting of he Workers League to celebrate the anniversary of the Paris Commune.

The theatre building, opened in 1908 by the famous vaudeville entrepreneur, survived the explosion, the Great Depression, two wars, and a century-long decline of the surrounding neighbourhood. But it may not survive the latest threat – gentrification.

Pantages is like many other familiar landmarks of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside – in danger of being swept away by a tide of renewal targeting the city’s last swath of “undeveloped” downtown.

The area around East Hastings and Main was once a bustling centre of commerce and retail. But after a worldwide economic slump in 1913, it increasingly became home to unemployed and transient blue-collar workers.

With the onset of the Depression, the neighbourhood’s low-rent hotels became habitats for the unemployed and dissenting elements of society; by the 1940s such hotels as the Patricia, Regent, Balmoral, and New Fountain supported slack-timing longshoremen, sailors, seasonal loggers, and fishermen.

The ground floor bars attached to such establishments developed a rough reputation as refuges for “dope fiends,” “sex perverts,” and the general criminal detritus of society.

Today, the neighbourhood, “infamous as the poorest postal code in Canada,” is once again in transition. Retailers who abandoned the area in the 1990s appear poised to return. And, pending an economic rebound, increased development of the area seems inevitable.

Fighting against this current of gentrification are a small number of operating hotel bars, which persist as relics of the early twentieth century. They remain open for business and are surprisingly intact.

No one alive in Vancouver today is more aware of their value than Jim Green, a former Vancouver city councillor and community activist.

“These buildings reflect a different time, when the economy was solely based on resource extraction and Canada was a maritime power,” says Green. “The reason these places existed was for the young men who would come out of the woods or off the docks or ships, often with money to spend, to live in these single-room hotels and drink [downstairs] in the bars.”

Green himself is part of that heritage. Born in Alabama, he came to Vancouver to avoid the draft during the Vietnam War. He was introduced to the downtown when he worked as a longshoreman in the 1970s. He was for a time a resident of the Patricia Hotel.

For nearly forty years, Green has battled greedy slumlords, local governments, and developers bent on gentrifying the downtown.

In the lead-up to the 1986 world’s fair in Vancouver, Green earned the title “Khadafi of the Downtown Eastside” for his uncompromising approach. Expo 86 was a disaster for low-income residents, many of whom were evicted to make way for higher-priced tourist hotels.

Green was sued and threatened by landlords opposed to his advocacy work, which culminated in his creation of what is known as the SRA (single-room accommodation) bylaw. Passed in 2003, it was created to protect hotel residents from eviction without cause.

The organizers of the 2010 Winter Olympics have moved to avoid bad publicity by ensuring that evictions similar to those that occurred in 1986 do not happen. But there is still intense pressure to sweep away the old in favour of new development.

Are the old hotels and associated buildings worth keeping?

Consider that each has a tale to tell about Vancouver’s past. Here are some of their stories:

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Regent Hotel - Pantages Theatre/160 & 152 East Hastings

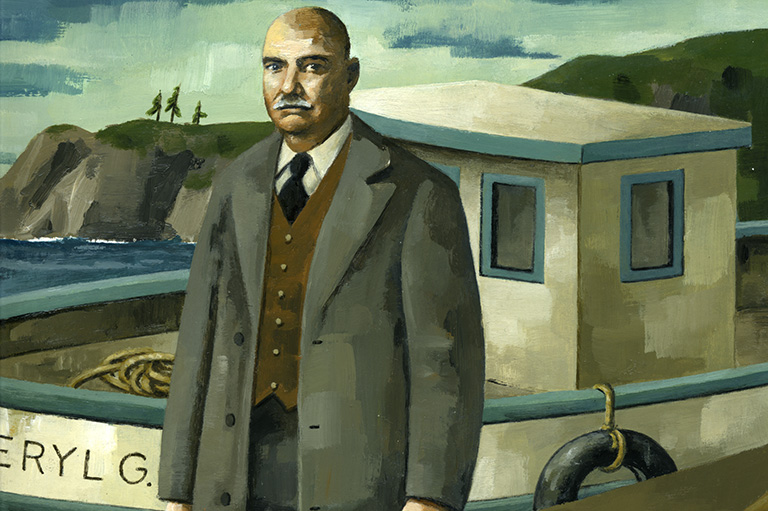

Long before his Vancouver theatre was conceived, built, or bombed, its original owner, Alexander Pantages, was one of nearly 40,000 prospectors who swarmed into British Columbia and Alaska in the wake of the Klondike gold rush.

According to legend, Pantages left his home in Greece at age nine, eventually jumping ship in San Francisco; the gold rush took him to Dawson City, where he managed his first theatre on Canadian soil.

Pantages went on to build a vaudeville empire that captivated North America. His theatre at Hastings and Main, the second in the Pantages chain, opened in 1908 with the Vancouver debut of Wallace the Untameable Lion.

The theatre was built by Pantages' silent partner, English-born B.C. real estate baron Archie Clemes, who also built the upscale Regent Hotel next door in 1913. Together, the two buildings were part of what became the Clemes Block.

But just ten years after its debut performance, the theatre became passé due to a “declining neighbourhood situation” and inadequate seating.

Pantages abandoned the venue, which went through several owners and, aside from the 1933 bombing, survived a fire in the projection booth and a huge scandal in 1953, which saw the entire cast and crew of a live production of Tobacco Road charged and convicted of staging an “immoral performance.”

The theatre has sat unused since 1994. As recently as last year, there were plans to restore Pantages to its original purpose as a live theatre venue. But those plans were scrapped after the owner was unable to reach an agreement with the city of Vancouver.

As of the summer of 2009, the site was up for sale and the seller was seeking a demolition permit for the building.

Drugs by Decade

On the edge of the opium dens of Vancouver’s Chinatown, illegal drugs always had a place in the Downtown Eastside, but the explosion of heoin use in the 1950s attracted a new generation of sex workers and drug addicts. In the late 1980s, cocaine displaced heroin as the drug of choice. Later, crack and crystal meth became more prevalent.

The Patricia Hotel/403 East Hastings

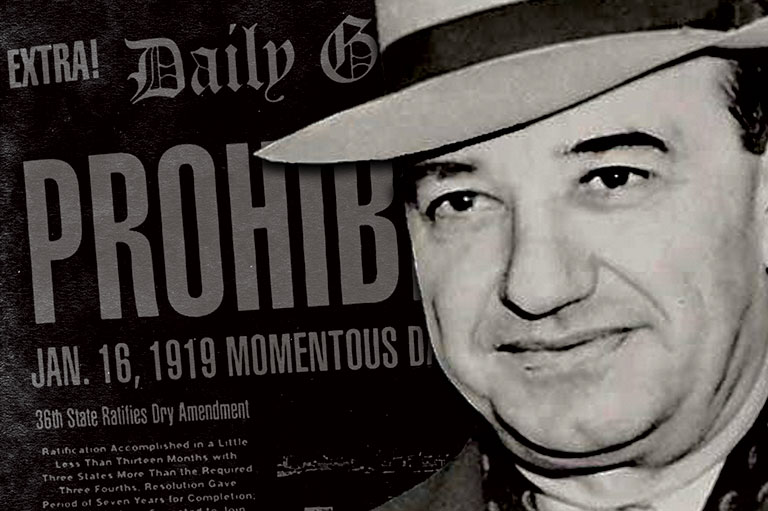

A referendum in 1920 ended Prohibition in B.C. at around the exact time Ferdinand “Jelly Roll” Morton, one of early jazz's most influential pianists and composers, rolled into town for an extended gig at the Patricia Cafe at 403 East Hastings. The cafe was part of the larger Patricia Hotel that still operates there today.

Singer Ada “Bricktop” Smith performed at the Patricia during the same period. She remembered facing a tough crowd of Swedish lumberjacks.

“Tall strapping fellows, they could make a bottle of whiskey disappear in no time,” wrote Bricktop of the customers at the Patricia Cafe in her autobiography. “Pretty soon they'd be drunk and ready to fight.”

Bricktop broke her leg during one such brawl on Christmas Eve of 1919.

In Guilty of Everything, Vancouver writer John Armstrong describes the long-standing customers of the Patricia and other hotels: “The working men came into town horny and rich, stayed until the money ran out, then made their way back to the woods or the ocean. A few months later they came back and did it again until one day they were too old to go back to work or were just too busted-up and crippled. Then they moved in permanently and learned how to make a glass of draft beer last four or five hours.”

Expo tragedy

In the lead-up to Expo 86 in Vancouver, downtown hotels evicted between five hundred and six hundred long-time tenants to make room for tourists. One of the tenants was retired logger Olaf Solheim, who had lived in room number 338 at the Patricia Hotel for sixty of his eighty-six years. Evicted with less than eight hours notice, Solheim died within six weeks. His death was linked to the stress of the eviction.

The New Fountain Hotel in 1969

Built in 1899, the New Fountain was originally part of the investment portfolio of Evans, Coleman and Evans, a business partnership that made a vast fortune in B.C. salmon canning, herring, forestry, and coal.

By the 1950s, it was among the area’s worst dives. In 1953, plainclothes health officers entered the New Fountain Hotel to observe a “male VD patient” jumping between the male and female sides of the New Fountain and neighbouring Stanley Hotel:

“During a ten-day drinking and sexual spree ... he picked up six women in these parlours, always walking directly into the woman’s entrance,” wrote Robert A. Campbell in Sit Down and Drink Your Beer.

Already a tough working-class bar by the early 1960s, the New Fountain found a new and steady clientele in the city’s gay community, including a growing subculture of cross-dressers who migrated west beginning in 1967 following a crackdown on vice by Montreal police.

In 1968, Vancouver Province reporter John Griffiths observed the following: “The ‘drag queens,’ a popular name of the female impersonators, appear in their wigs, miniskirts, black net stockings and high heels ... often given away only by their muscular legs ... adding dramatically to the scene of revulsion.”

In 1968, the city refused to renew the lease for the New Fountain and the Stanley Hotel next door. It was reopened in the early 1970s as Vancouver’s first privately developed rent-controlled social housing development. Today, the Stanley-New Fountain Hotel is a city-owned shelter.

When Canada entered World War II, hotel-based beer parlours were seen as a breeding ground for venereal disease among soldiers. One provincial Board of Health official referred to beer parlours “frequented by diseased women” as an “alien fifth column which is insidiously undermining the health of His Majesty’s Forces.”

The solution was to physically separate men and women.

By April 1942, all Vancouver parlours were required to install partitions at least two metres high so that men and women could not see each other. Several of the remaining bar hotels on the strip – most notably the Balmoral and the Empress – still have separate entrances for men and women.

Lotus Hotel/455 Abbott

A two-page Vancouver Sun advertisement in January 1913 heralded the Lotus as “a marvel of modern equipment, elegance and luxury” that was “absolutely fireproof, sound-proof and vermin-proof.” It had an eighteen-metre-long mahogany bar, hammered bronze chandeliers, and multiple stained glass panels.

By the late 1940s, it was still making headlines – but for different reasons. It was now the scene of shootings, illegal liquor sales, and bookmaking. Of all the beer parlours hotels in Vancouver, the Lotus attracted the most heat for illegal gambling.

But police presence at the Lotus diminished dramatically in October of 1956, when Vancouver Police Chief Walter Mulligan resigned amid accusations of taking bribes from bookmakers.

The hotel bars of the Downtown Eastside today attract more international tourists, artists, and college-aged partiers than at any time in the last century.

“The hipsters have discovered the Downtown Eastside,” says David Eby, a lawyer and the executive director of the B.C. Civil Liberties Association. “The Lotus today is still a hotel, but the ground floor has transformed into a really popular dance club.”

Last year, the pub in the Patricia Hotel – which includes the original dance floor that dates from before the time of Jelly Roll Morton himself – was born again as a venue for rock and punk bands, as have other gritty Hastings Street hotel bars like the Balmoral and Astoria.

Even the Regent Hotel, which today contains one of the roughest bars left on the strip, is attracting young adventure tourists and locals who enjoy drinking ultra-cheap draft beer shoulder to shoulder with grizzled resource industry veterans, sex trade workers, and addled substance abusers.

The reason a new generation is being attracted to the hotel bars today, says Jim Green, is that such venues possess an authenticity that cannot be found in any other Vancouver neighbourhood, let alone be replaced by new glass-and-steel towers.

“Nobody on earth would build these kind of buildings now, and even some of the big hotel neon signs are still there and fabulous,” says Green. “Building all of that now would just be too expensive.”

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.