HBC History Has a Hawaiian Chapter

When Canadians think about the Hudson's Bay Company's long history, they usually think of beavers, cold northern outposts, fur brigades, and a vast resource of archives. Few think of palm trees and hula dancers.

As unlikely as it seems, Hawaii was the site of an HBC post from 1834 to 1859. And it proved rather popular too.

The Honolulu store offered fixed prices and liberal credit terms. West coast salmon was particularly sought after. The story of HBC's post in Honolulu was described in the September 1941 issue of The Beaver. You can read the story below.

Beaver In Hawaii

It was over a hundred years ago that the Sandwich Island agency of the Hudson’s Bay Company was established in Honolulu. George Pelly, a close relative of Governor Sir John Pelly, came from London in 1834, and after carefully looking over the islands in the interests of the Company, decided that an office should do well there. Previous to Pelly’s arrival from England the interests of the firm had been handled by Richard Charlton, the British consul at that time.

After the establishment of the agency a shipload of goods was brought in annually from England for sale in the islands. The Company vessels would often stop at Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River, on the way out from England, and pick up lumber from Dr. McLoughlin’s pioneer sawmill and barrels of salt salmon.

This salt salmon soon became popular with the Hawaiians. They would slice it up into small bits, and with the addition of tomatoes, green onions, water and ice would serve up a tasty dish called lomi lomi salmon. On the outgoing voyage from the islands the vessels carried Hawaiian salt, molasses, sugar and coffee.

In 1836, the Sandwich Island Gazette, first English language newspaper published in the islands, made its appearance. The issue of August 5, 1837, carried an advertisement for the Hudson’s Bay Company agency, reproduced herewith, announcing that the brig Lama has arrived from the Columbia, bringing 30,000 feet of inch boards, seventy 18-foot beams 12x4 inches, and 500 rafters.

This advertisement was changed March 31, 1838, to note further lumber supplies, as well as salmon, butter, flour, etc., by the Company’s barque Nereide, followed by one in December of like supplies by the Columbia, and again in February, 1839, by the Nereide.

Whenever such shipments arrived in the islands, the Hawaiians made light work of removing the cargoes from the vessels to the warehouses of the Company. Pelly became impressed with the physical power of these natives.

He knew, moreover, that back in 1829 six fearless Hawaiians had helped to save Fort Umpqua during an attack by the Indians. And in 1840 we find him making arrangements with Governor Kekuanaoa of Oahu to permit the Company to take sixty Sandwich Islanders to the Columbia River post for a period of three years.

At the end of this time the Hawaiians were to be returned. The penalty for non-return would be $20.00 each, except in the case of death.

The Company ships plying to Honolulu sometimes carried notable passengers too. Rev. Herbert Beaver arrived there in 1836 from London on his way to Fort Vancouver. Alexander Simpson, brother of Thomas, came in 1841.

His famous cousin, Sir George, arrived the following year on his journey round the world, bringing with him on the Cowlitz Dr. McLoughlin, John Rowand of Fort Edmonton, and his own secretary, Edward Hopkins. These three returned to the Columbia on the Vancouver, wile Simpson on the Cowlitz headed for Sitka, accompanied by Charlton and Pelly. As they left the harbor they were saluted by the guns of the Fort.

By that time, George T. Allan, whom Simpson in his book refers to as “an officer in our regular service,” had joined Pelly in Honolulu. Under this partnership the Hudson’s Bay Company in Hawaii waxed and grew mightily, becoming a financial and commercial power in the islands.

For one thing the Company always maintained a one-price store. The rate was the same whether one bought singly or in dozen lots. The good quality of the merchandise was a known fact.

Most important, perhaps, was the liberal credit plan of the Company. Selling on the “easy pay plan” had already proven of some merit even then, and was one of the factors which helped to make the Company’s store one of the leading mercantile houses in Hawaii.

The agency was also financially sound, as good-sized loans were at various intervals made to envoys of the Hawaiian government in England and on the continent when they were in need. These little courtesies on the part of the Company helped to strengthen and added to the good will of the Hudson’s Bay Company in Hawaii.

Following the formation of a constitutional form of government in Hawaii, the first tariff act was approved May 11, 1842, and took effect the following year on January 1. The first vessel to make customs entry and to pay the ad valorem duty at three percent was the Hudson’s Bay barque Vancouver from the Columbia River, January 6, 1843.

The vessel’s cargo consisted of 695 barrels of Columbia River salmon valued at $4,170, a tidy sum in those days, and 160 twelve-foot four-inch planks valued at $307.20. On this amount $134.32 in duty was collected.

Through the Company’s friendly dealings, and the words of praise from Company officials for the people of the Hawaiian kingdom, Great Britain took a fatherly interest in the people of Hawaii. Even in those times, England played the role of protector and not that of the aggressor or dictator.

When in 1843 it became known that the French had designs on the Hawaiian Islands after they had taken over Tahiti and made a colony of it, Lord George Paulet, commanding Her Majesty’s frigate Carysfort, was dispatched from the coast of Mexico to the Hawaiian Islands to see that no outside nation should interfere and try to subdue the peace-loving natives.

At that time, the Hawaiian people did not know that this was England’s motive for keeping her warship in Hawaiian waters for five months until danger from invasion by the French had passed.

This laudable act of Great Britain was brought to light through the efforts of the Hawaiian Historical Commission in 1925. When this commission was given access to the British Archives, diligent research was made of this act of the British, and the above motive of protection for the Hawaiian people was confirmed.

The same commission, however, was forbidden to do any research in the French archives.

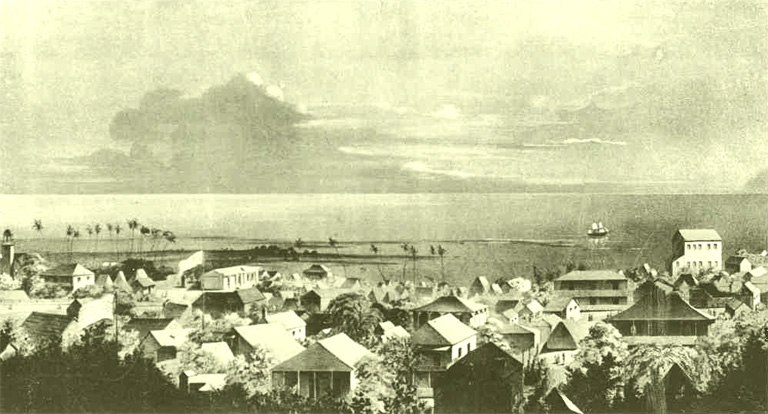

The Company’s first store at the corner of King and Nuuanu Streets was a bit up-town in those days. In 1846, preparations were made for moving it nearer the waterfront—a logical choice for a company in the importing business.

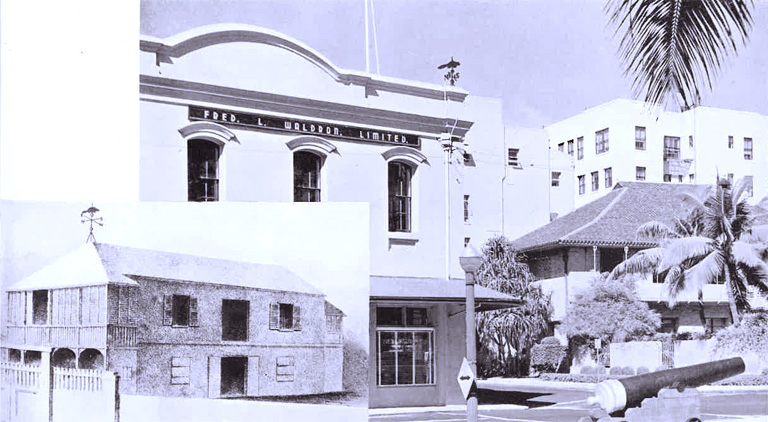

By the end of the year they had moved into a two-story building at the corner of Fort and Queen Streets. Here business was carried on as briskly as ever. This last location remained the Company’s place of business for the years which followed.

Pelly, the original agent for the Company in Hawaii, even though he became a landowner with a residence in town and a country home in cool Nuuanu Valley, never forgot his dear old England. Perhaps, feeling that he had established the Company in Hawaii and that his work was over, he sailed for his homeland after disposing of his property.

Other representatives who came and took charge of the Company’s affairs were: Dugald MacTavish, David McLoughlin, Robert Clouston, and James Bissett.

James Bissett arrived in Hawaii, January 28, 1859. The former agent, Robert Clouston, had left Honolulu by barque Fanny Major in August, 1858, for San Francisco, for a rest and change. After a brief illness of just four day’s duration on the homeward voyage, he died, and was buried at sea.

There was a lapse of four months before Bissett arrived to take charge of the Company’s affairs in the islands. Under his guidance the Company continued to carry on its business as in the past, but on November 26, 1859, the people of Honolulu were amazed to read a notice in the Polynesian, announcing the Hudson’s Bay Company’s withdrawal from the Hawaiian Islands. James Bissett’s name as agent appeared at the bottom of the notice.

All the holdings of the Company were advertised at reduced prices for quick sale, but even then it took some months finally to wind up its affairs.

Mr. Bissett, his wife and child, left the Hawaiian Islands for Victoria on the barquentine Jenny Ford, August 25, 1860.

The reason for the Company’s withdrawal from the Hawaiian Islands may be better explained by quoting the Polynesian, which paid the Company the following tribute:

“As a mercantile house, in all that constitutes the credit and glory of a merchant, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s agency in Honolulu stood in the foremost rank. It was for years a sort of commercial moderator, a mercantile balance wheel when fluctuations seized on others. Their withdrawal from Honolulu was understood to be owing to the fact that the discovery of gold mines on Fraser River and consequent settlement gave new employment for the capital of the Company near home.”

The Hudson’s Bay Company may have left the islands in 1859, but the memory of the Company did not pass like a ripple on the water or a breeze in the air.

Today, in 1941, on top of Fred. L. Waldron’s building at the corner of Fort and Queens Streets, the site of the last Hudson’s Bay Company’s store in Honolulu, a weathervane turns listlessly in the tropical winds. And the silhouette it presents against the sky is that of a beaver.

On warm days, when the wind is from the south, people riding or walking along Honolulu’s busy waterfront look up at the beaver and study it, as George Pelly must often have done, for some indication of a return to the cool trade winds from the northwest.

Nor is the weathervane the only reminder of the Company. Under the roof below the beaver, just a few doors up Fort Street, is the Merchant’s Grill. And in a prominent place toward the rear of the restaurant, visible from all parts of the room, is another beaver.

This one has been carved from wood and is of an Ethiopian hue. At the Grill, prominent business leaders and captains of island industry gather for their noonday meal. An inquisitive tourist saunters in looking for lomi lomi salmon.

“Yes, we have iced lomi lomi salmon,” the tourist is informed by the genial head waiter.

“I’ll try some. I’ve heard much about it.”

“You’ll enjoy it, madame.”

“Waiter, is this a truly Hawaiian dish?”

With a twinkle in his eye, the waiter will nod in the direction of the beaver. “Yes, madame; you see, salt salmon — it came over with that beaver.”

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement