Christmas at Moose Factory

Our dog-team journey up James Bay just before Christmas was for business. Doug Sinclair and I were making Fur Country, a colour film on trapping for the National Film Board of Canada. In Fur Country we recorded certain phases of northern life in winter; but we could not possibly put into the film those Christmas scenes of which we ourselves were a part — scenes of the winter holiday season in the North which few visitors witness.

We arrived at Moose Factory early in December 1941, and by the fifteenth had organized an expedition to Hannah Bay to shoot key scenes for the film. The trip took two days.

After a week or so we moved to Waskouga Creek, some seven or eight miles back along the homeward trail. We broke camp at Waskouga Creek around noon on December 23rd, confident we’d reach Moose Factory the next afternoon. But the Bay trail was unusually rough, and by the afternoon of the day before Christmas we were hardly half way to Moose Factory.

More than ever the feeling grew that we were in the bottom of a gigantic saucer, its white sides sloping all around us. The more we struggled, the more in the bottom we found ourselves.

They call it an optical illusion. But our experience tells me that it is reality, that the ice on James Bay is not, cannot be flat. Continually we were climbing—not up a steep grade, but up the gradual interminable kind that breaks back and spirit.

Ice block and snow-drift kept catching the sleigh. Then we’d throw our weight against the tarpaulin covered load and heave; or we’d haul on the peto and start the runners that way; and all the while we’d be yelling the driving calls of the Bay —Hwitt! Hwit!, Oke! Oke!, or Hurraugh! Hurraugh!

George Moore, our guide, was far ahead, finding the best trail (if trail there were in that chaos of jagged ice ridges and piled snow). The dogs, apparently knowing George, their master and match, was out of call, did what they pleased. What pleased them most was to lie down on the job!

“Will we get to Moose Factory tonight, George?” we’d ask whenever he came back to the sleigh.

“I guess so. I ought to find a good tide-mark soon.”

The day before Christmas, I thought, as we tugged and yelled, and Christmas dinner would be waiting for us at the Watts’ tomorrow (Mr. Watt, manager of the Hudson’s Bay Company post, had asked us before we set out on the trail).

Rime was blowing in from the open water far out on the Bay and snow was falling lightly. On and on we struggled up the maliciously receding sides of the saucer for what seemed hours.

Ahead, George had stopped again, was waiting for us. The dogs spurted unexpectedly, leaving us both behind.

“I don’t think we’ll get to Moose Factory tonight,” were the words with which George greeted us. “What’ll we do?”

“Camp,” he answered. “Fellow used to have a shack for duck hunting at Partridge Creek. We’ll go there.”

Partridge Creek—Pag-sag-wa-ow it sounded like when George gave it its name—suggested sheltered bush coverts for those little game birds of the North. But when, in the failing light, George told us we’d entered the creek’s channel, we knew’ its shores, lined with a few low and scraggly willows, were as dreary as the open ice of the Bay.

George found a snow-drift contour which told him a tent had once been pitched on the spot. We all dug into the snow’ and uncovered camping luxuries—straw, empty cartons, firewood.

I don’t yet know where George got tent poles. I only know he did. And the tent was up and there were willows and straw for our sleeping bags, and the stove was going, and Doug and I were squatting practically on top of it, drying our underwear.

We’d dried our pants first—dried them on us—and we were doing the same for our underwear; it was too cold to take any clothes off.

The hungry dogs, smelling the sausage frying, began to bark mournfully, as if they hadn’t the energy to howl, as if they knew George had given them the last of their feed the night before.

The dogs went to bed supperless; but they at least were used to sleeping in the snow. We weren’t—not even after our weeks on the trail—and our last night seemed the coldest, the most uncomfortable and discouraging of all.

Maybe it was because we were so tired, maybe because we knew this was Christmas Eve and our friends would be celebrating in warm cheerful rooms while we were out in the cold bush, with chill air seeping through the willows under our sleeping bags.

Christmas Eve may have been long, but Christmas morning was longer. We were on the trail early; and after what seemed a whole day—though it was only part of the morning—we reached the mouth of the Moose River, eight miles from the post.

The snow was too deep on the river for the team to pull the sleigh with even one of us on it. George, anxious to be home, was hurrying. We could only try to keep up with him...

It was unbelievable that we were actually sitting at a table again and eating such a Christmas dinner as Mrs. Watt had provided — turkey, plum pudding, all the trimmings!

The white wastes of the Bay through which we’d fought, the cold brown canvas under which we’d slept, the tasteless fried dry foods we’d eaten— these were becoming somehow unreal even in our memory. It was as though our lives had begun when we returned to Moose Factory at three o’clock in the afternoon of Christmas day.

We knew the Bay’s desolation surrounded us, with occasionally a team moving out on the ice, the only sign of human life in vast frozen stretches.

After we returned from the trail the employee families at the post took us into their congenially self-contained little circle. Doug thought it was because we’d passed the test of the trail acceptably in their eyes.

I wasn’t thinking. I was just enjoying to the full this group of new friends — Mr. and Mrs. Watt; Dr. Orford (with whom, incidentally, I’d gone to high school in Northern Ontario) and Mrs. Orford (with her rich Scotch wit); R.C.M.P. Sergeant and Mrs. Dexter; Corporal Wilson, the other “Mountie,”; and Art Sanborn, the Company clerk.

In the few days since Christmas, Doug and I had come to know and care for these people greatly, to admire them for their northern qualities.

But it was one night at Dr. Orford’s that we really saw these northern qualities in action. The Christmas tree was already shedding its needles, for stoves raise inside temperatures to new heights of dryness.

The room rang with Scotch accents — synonymous, we were learning, with the Hudson’s Bay Company northern personnel. We were watching the doctor’s 8-mm. moving pictures: Baffin Island’s treeless contours; the bewigged dignity of the Law outside the tent courtroom on the Belchers during the 1941 trial of the religion-twisted Inuit; the doctor’s “treaty” trips up the Bay.

“Here comes Jimmy Watt,” Mrs. Orford said, exactly as if the man and not his screen shadow were entering the room.

Hers was the first of many similar exclamatory greetings. As Doug and I listened, we realized how close to one another, even though separated by miles of bush, were these Northerners; how fully they accepted one another; what genuine pleasure they felt when business took them to the posts where the others were stationed, or brought the others to theirs.

During the movies the door opened and Priscilla, the doctor’s eleven-year-old daughter, came quickly into the room. Obviously excited, she wore neither hat nor overcoat, but her voice was quiet:

“Father, Billie was heating the dog’s supper and — the can exploded in his face. Some got in his eyes. Will you come?”

The doctor was out of the door almost before Priscilla finished speaking.

“I think we’d better go, too, Bill,” Mrs. Watt was saying in a calm, unhurried tone to her husband; but the rapidity with which she went to the hall and slipped into her blanket coat showed her inner feelings.

Billie was her fifteen-year-old son — the Watts’ only child. Mr. Watt, right behind her, grabbed his fur cap from the hook and followed her out of the door.

I thought: This, then, is how Northern people face an emergency. No one knew how badly Billie might have been burned — a boiling can, if opened without the greatest care, will violently spurt its scalding contents. Yet Mrs. Watt had made a casual statement and quietly but quickly gone to her son.

And Priscilla, who had seen the accident, had come as quietly and quickly for her father. The people of the North all had this self-reliance, self-command (call it what you will), which those who have always lived in settled southern communities so often lack.

Priscilla had spent her early childhood at Pangnirtung, away from other school children. This, I felt, accounted for her mature manner that at the same time was so natural. From isolated necessity, she had been much with her parents and other grown-ups, been accepted by them on equal terms.

I noticed this equality between parents and children at Moose Factory — fringe of the real North though it was; it was a northern quality I admired, fine, full, strong, beautiful.

“We can finish the movies,” Mrs. Orford was saying. “The others have seen them before.”

But none of us wanted to. We tried to talk about something general, but the conversation kept swinging back to Billie, and what might have happened in the Watts’ home across the way. And we sat and waited in that hot, bright room for what seemed hours.

Finally the doctor and the Watts returned. Billie might have to wear an eye shield for a day or two, but his burns were superficial.

The movie projector was again started; the absent northern personalities were in the room with those actually present; and the evening continued as it had begun, in the relaxed intimacy of these friendly people.

1942 had arrived and Doug and I were alone with Sergeant and Mrs. Dexter and Corporal Wilson in the living room of the R.C.M.P. quarters. The Watts and Orfords had been with us earlier, but had returned to their own homes to be ready for the Cree, for whom we likewise were waiting.

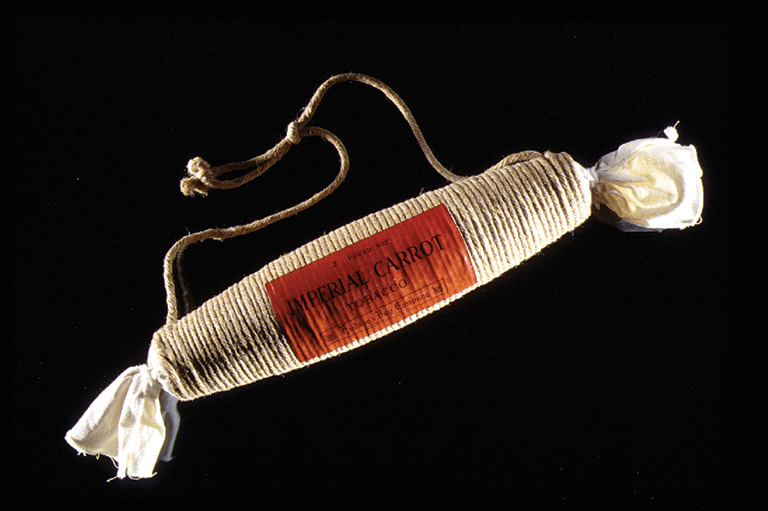

Then we heard the guns in the distance. The Hudson’s Bay Company at Moose Factory supplied the Cree with a ration of black powder shells for a New Year’s salute before every house in the settlement.

Soon many moccasined feet were crunching up the snowy path outside. A faint tinkly tune began even before the Dexters reached the front door. When they opened it we saw the fiddler and the man with the triangle, heard the guitar player. The tune was Scotch. “The White Cockade,” reserved by the Moose Cree First Nations for this New Year’s custom.

Then the music ceased and a voice as inflectionless as the music had been syncopated was saying: “We wish Mr. and Mrs. Dexter and Mr. Wilson a Happy New Year.”

No guns were fired, for the Cree respected the sleep of the Dexters’ infant son. Down the path and through the gateway in the cross-picketed fence they went, their raised parka hoods mysterious, magi-like shapes, moving through the blue-white night that was filled with the murmur of voices, the crisp squeaking of dry packed snow underfoot, and the echoes, silent but still present of the “White Cockade.”

We heard that plaintive music once again before New Year’s Day was over, at an feast and dance. Somebody opened the door of the house where the affair was taking place before we reached it, and out into the darkness of the night streamed a cloud of steam, lighted from within, eerily mysterious, holding a magic like music in its swirl.

Doug and I had the feeling we were lifting a veil as we passed through it into the kitchen and then into the room where the locals were dancing. Lamps, in the corners, lit the green wallpaper, against which the people in the room were silhouetted.

There were no shadows on the walls, where they should have been. The people in front of the walls had become the shadows of the room. The music pulsed. The syncopation of its rhythm was not what we’d imagined the music of northern First Nations would be like.

It held a warmth that was strangely in key with the tropical green of the walls. The musicians sat against one side of the room, holding their instruments casually, low. The fiddler used his bow with short strokes, as he would have handled a canoe paddle. The drummer kept his hand with the drumstick on the rim of the drum, beat it without raising his hand. Their music had a thin yet deep relentlessness.

Then they were doing the “duck dance” for us—for us, “the photographers,” as they called us.

“The old people remember the dance now. It’s Cree — goes way back,” our guide had told us. “Only a few of the younger ones know the steps — they’re hard to do. They play one tune for it— never use that tune for any other dance.”

The music grew more relentless. The tune undoubtedly was originally Scotch, but, as they played it, had a barbaric, primitive quality that matched the shuffling, bobbing, ducking figures which eight couples were executing to it.

Occasionally, across the insistent, disturbing rhythm of the moose-hide drums, came voices no longer human — giving the Bay’s hunting call for ducks—Quack! Quack! Quack! And those dark dancing shadows became, for us, ducks waddling.

From the desolation of the winter bay we’d come to the comfort of the modern homes at Moose Factory. Then we’d suddenly been thrown back to the primitive by the New Year’s tune and the shuffling duck dance.

That was our 1941 Christmas Holiday at Moose Factory. And from each of its episodes came to us a glimpse of the North — glimpses, we knew, which we would never have had if we’d come as holiday seekers in fair summer weather, instead of movie workers in the depth of winter.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement