Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Chiefs Journey

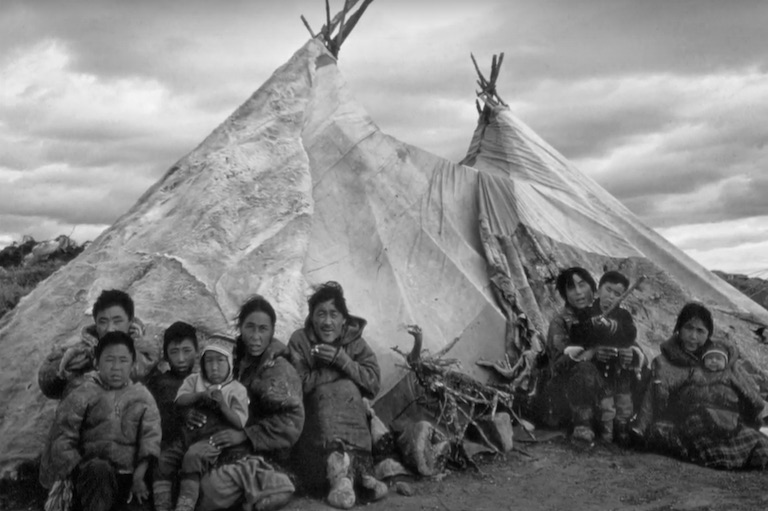

In 1886 John A. Macdonald invited a number of prominent chiefs who remained loyal during the Northwest Rebellion of 1885 to travel to Central Canada. The prime minister wanted these important leaders of the 15,000 or so Prairie First Nations to visit southern Ontario and Quebec (which then had a combined population of over three million1), in order to impress them with the Dominion’s numerical and technological strength.

Thomas Green, a Mohawk surveyor who had graduated from McGill University and at the time worked in the North-West Territories, had encouraged the prime minister. From Regina in March 1886 Green wrote: “Show them, or at least, allow them to be shown the principal sights & cities of Ontario & Quebec, and above all, have them visit the most prosperous Indian reserves of these provinces…. Let them see how their Indian brethren are prospering in those provinces; let them understand that the Indian can subsist like the white man where there is no game; and let them understand that the government do not wish to exterminate them.”2

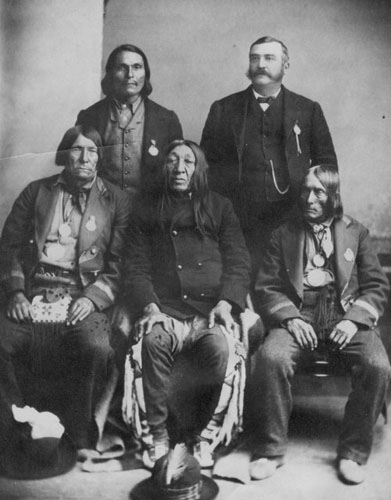

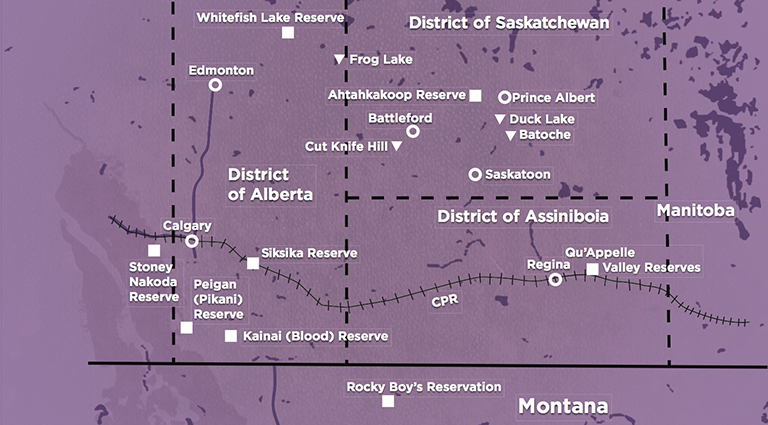

The federal government sponsored two separate visits: The first consisted of five Blackfoot speakers from Alberta; the second included three Cree chiefs and one Saulteux (Ojibwe) from Saskatchewan. Rev. John McDougall independently organized a third group of three “loyal chiefs,” two Cree and one Stoney Nakoda from Alberta.

The previous year the Methodist (now the United Church of Canada) missionary served as guide, scout, and chaplain with the Alberta Field Force, part of the Canadian forces organized to fight Louis Riel.3 The best-known Protestant missionary on the Canadian Plains4 paid for the tour entirely with voluntary contributions from Methodist congregations throughout Ontario and Montreal.

None of the First Nations’ impressions of their trips are directly recorded. In the late nineteenth century, few Plains First Nations people knew spoken and written English or French. As Métis scholar Emma LaRocque has written: “It is a great loss to Canadian knowledge that, with the exception of Riel, western Native peoples were not able to tell us in their own written words the encounters and the facts of the invasion processes as these things happened to them.”5

Fortunately press coverage does exist as well as the commentaries of both Rev. John McDougall, and Rev. John Maclean, the Blackfoot-speaking Methodist missionary to the Bloods in southern Alberta. The Blackfoot-speaking group from Alberta travelled in two parties. Crowfoot, the renowned Blackfoot chief, and his foster brother, Three Bulls, departed September 25 from the Blackfoot or Siksika reserve east of Calgary.6

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

From their reserves to the south of Calgary the well-respected Blood Chief, Red Crow, his pipe carrier, One Spot, and North Axe, the newly elected chief of the Peigans, left at the beginning of October. The Blackfoot Confederacy members travelled with two interpreters. The first, Jean L’Heureux, was a colourful French Canadian who at times masqueraded as an ordained Catholic priest. For roughly two decades he had lived with the Blackfoot. On account of his linguistic skill in Blackfoot, both the Catholic Church and the Indian Department employed him as an interpreter.7

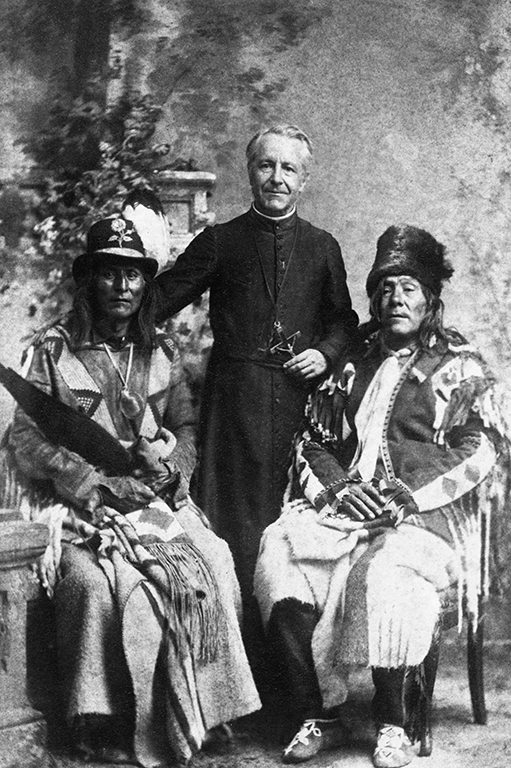

The second individual, the legendary Roman Catholic priest Father Albert Lacombe, well respected by Native and non-Native alike, joined them in Ottawa, and accompanied them to Montreal and Quebec City. He spoke both Cree and Blackfoot.8

Nine years earlier, on September 22, 1877, the four nations of the Blackfoot Confederacy (Blackfoot, Blood, Peigan, and Tsuu T’ina) and the Stoney Nakoda had signed Treaty Seven. Each side came to the negotiations in early fall 1877 with their own agenda. The Blackfoot had wanted the Cree, Métis and other outsiders from the north and east expelled from their hunting grounds. They also wanted protection provided for the remaining buffalo herds.

The Canadians sought title to First Nations’ lands. In the words of historian Hugh Dempsey in his recent book, The Great Blackfoot Treaties (2015): “In the end, the Blackfoot got neither and the government got all.” But, he pointed out a benefit for the First Nations: “Without realizing it, the Blackfoot and Stoneys established a relationship with the government that would ultimately save many lives when the buffalo were destroyed and in the end — although this was perhaps not understood at the time — the reserves became havens for a dispossessed people.”9

The buffalo disappeared on the Canadian side of the forty-ninth parallel in 1879, and on the American side in 1883.

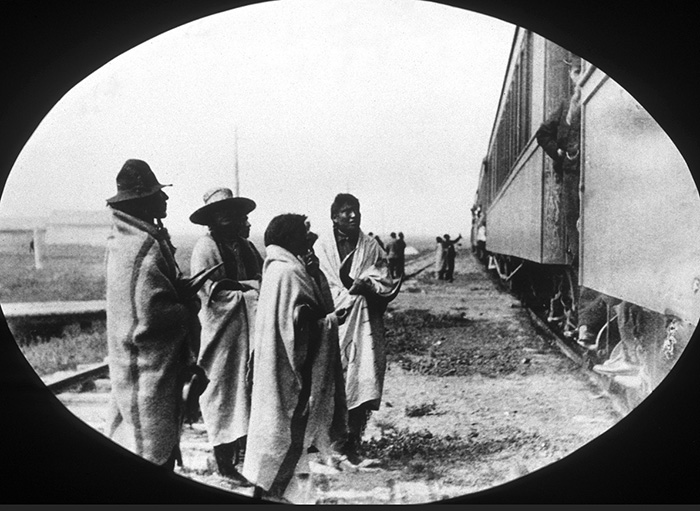

By the fall of 1886, when the chiefs embarked on their journey, transcontinental train service on the CPR had only been in existence for several months. The chiefs travelled in an hour approximately the same distance one could cover on a horse in day.10

According to Dempsey in The CPR West, the prairie people had a name — “fire wagon” — for the huge objects that moved like wagons and breathed fire as they went. It was not their first time on a train. Two years earlier, in 1884, Crowfoot, Three Bulls, with Red Crow, and Eagle Tail, had made a train journey when the line was completed across the prairies.

The impact on them of their 1884 train trip is mostly unrecorded. It must have been considerable. Plains Indians regarded the earth as a flat expanse of land dominated by natural features such as the Rocky Mountains that they called, “The Backbone of the World.” 11

Now the Blackfoot travelled to the outermost extremities of their known world, first to Regina, population roughly four hundred,12 then on to Winnipeg, a city with a population of over 15,000.13 In Winnipeg Red Crow enjoyed his first dish of ice cream, a new delight that he called “sweet snow.”14

In late September 1886 Crowfoot and Three Bulls again travelled back though Regina, and Winnipeg, whose populations had grown. (Winnipeg now had 20,00015 people.) They were en route via Ottawa to Montreal, with a population of approximately 200,000.16 The majority in Montreal Canada’s largest city were French Canadians, who the Blackfoot to this day call “real white men,”17 as the French were the first Europeans the Blackfoot had met.

In this massive settlement the buidings made those in Winnipeg look small. The two Blackfoot stayed in what they called “otas”, huge homes with many rooms, each with windows. As there is no “h” or “l” in Blackfoot,18 “ota” is how they pronounced “hotel.” With interpreter Lacombe, Crowfoot and Three Bulls visited many churches and public buildings, the dockyards, and a number of city businesses, one of which was the headquarters of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Crowfoot constantly wore in his hair his holy protector, an owl’s head. It had holy songs to go with it.19 Neither Crowfoot nor any of the other Blackfoot-speaking travellers had converted to Christianity.

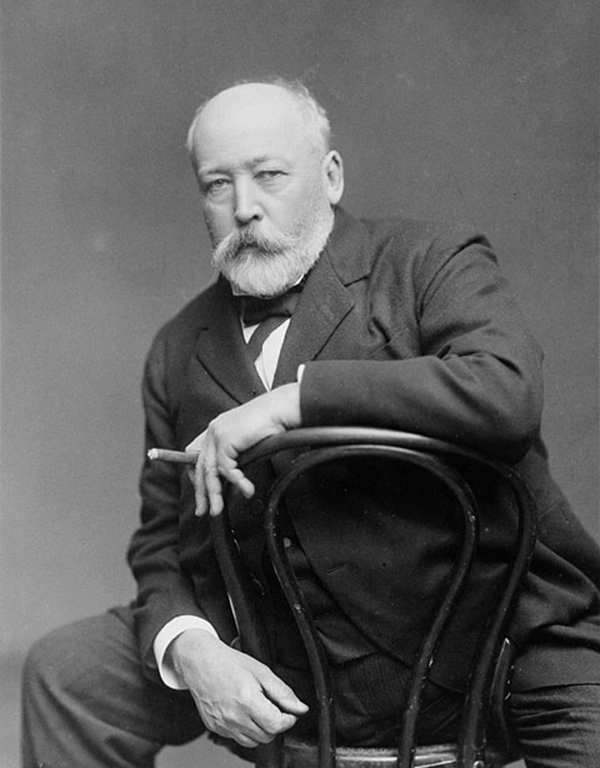

Speeding locomotives, belching sparks as they thundered past, had caused prairie fires on the Blackfoot reserve. Horses had been struck and killed.20 In Montreal Crowfoot discussed his concerns with CPR president William Van Horne. Earlier that year the Blackfoot head chief had told a Toronto journalist, “Last year we asked for damages but have yet received no answer. If this harm was done in the white man’s country it would be redressed.”21

Van Horne gave Crowfoot a perpetual pass on the line, but provided no compensation for the damage caused by the trains.22 Crowfoot’s fight with the railway continued until his death four years later in 1890.23

In Montreal the two Blackfoot heard unusual sounds in the streets. The languages spoken were little more than a babble of noise. The high level of sound was constant during the weekdays. The huge crowds exceeded anything they had ever experienced. The old buffalo hunters moved carefully amongst carts, horse-drawn carriages, pedestrians, street vendors, and beggars. The stark contrast between the rich and poor was so obvious.

On the plains no matter how brave a man might have been, or successful in war, one could not hope to become a leader unless he was kind-hearted and willing to share with everyone in camp.24 Later Red Crow and North Axe after their journey to Central Canada told their fellow Bloods and Peigans when they returned: “In many things the white men were inferior to the Indians, and that they were white savages.”25

The “white savages” had strange customs, such as different approaches to the timing of meals. Rev. John Maclean spent eight years with the Bloods in the 1880s. In their own country he noted, “They eat and sleep when they feel disposed.”26

On tour, the visiting chiefs must now gather at stated times in dining halls. Did they sit and eat cross-legged on the floor? At meals did they avoid the alien fork, and instead use only a knife and their hands to eat, as was their custom? How much did the visitors eat? Only ten years earlier warriors in the buffalo days consumed huge amounts of meat in a single sitting.

Usually the pot was kept boiling at all times, and family members helped themselves whenever hungry.27 The food they ate in Central Canada was new, not the reliable boiled beef, bannock, and tea, now their standard fare back home.28 Did they eat such things as pies, custards, and sweets when offered them? Their lack of exercise took its toll.

A Toronto Globe story on September 2 reported that Chief Pakan, one of the Methodist loyal chiefs from Alberta, “who weighed 180 pounds when he first reached Toronto now weighs 205 — a clear gain of twenty-five pounds in one month.”29

An estimated 7,000 people came out to see Crowfoot and Three Bulls at the St. Peter’s Cathedral bazaar.30 The press and the public lionized Crowfoot. His proud bearing, colourful regalia, and thin hawk-like face fitted perfectly with the public’s conception of a great chief.31

The Montreal Star commented on his voice: “Sonorous, well inflected, and evidently one accustomed to command.”32 Honoré Beaugrand, Montreal mayor and founder of one of the city’s great dailies, La Patrie,33 warmly greeted Crowfoot and Three Bulls at the cathedral.34

They next spent three days in Quebec City, a city with one-third of Montreal’s population. L’Heureux returned to the prairies to escort Red Crow, One Spot, and North Axe to Ottawa.35 With Father Lacombe as their guide-interpreter, the two Blackfoot visited the Quebec legislature, where Crowfoot was allowed to sit in the Speaker’s chair.36 They were introduced to John Jones Ross, the premier of Quebec — who despite his British-sounding name, was a French Canadian.37

They went to the Livernois studio where a photographer took several images.38 In the afternoon they toured the Quebec Citadel whose strong defences, cannons, and guards in attendance greatly impressed Crowfoot.39 By the time they arrived back in Ottawa on October 8, Crowfoot was in poor health and totally exhausted. They returned to the federal capital, just before Red Crow, One Spot, and North Axe stepped off the train with L’Heureux.

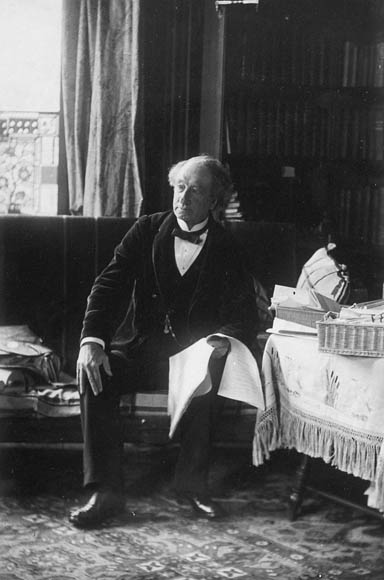

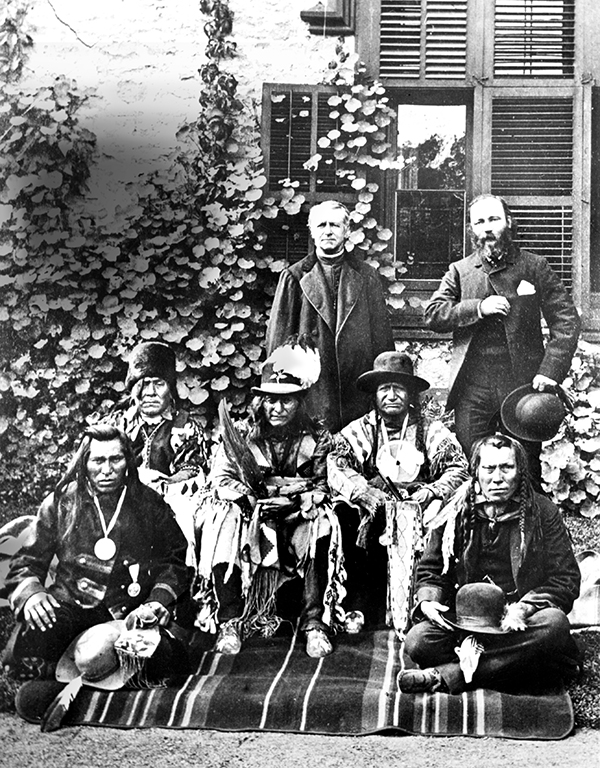

The prime minister invited all five Blackfoot visitors to his home. A photographer took an excellent photo of his guests, with their interpreters, on the lawn in front of Earnscliffe on Saturday morning October 9.40

The comfortable home, which is today the residence of the High Commissioner for the United Kingdom in Canada, is located on a spectacular site on top of the limestone cliffs overlooking the Ottawa River, with a fine view across the river to the Gatineau Hills.41 Before the photo session Macdonald and Crowfoot spoke together in Earnscliffe’s parlour or sitting room, with Father Lacombe interpreting.42

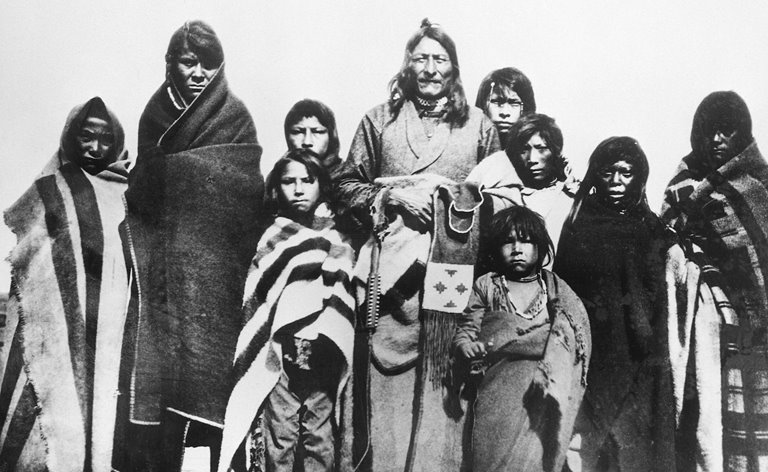

The disappearance of the Plains buffalo herds ended a way of life thousands of years old. As Edgar Dewdney, the Indian Commissioner in the North-West Territories, reported back to Macdonald from Blackfoot country in January 1880: “Young men who were known to be stout and hearty fellows some months ago were quite emaciated and so weak they could hardly work; the old people and widows, who, with their children live on the charity of the younger, and more prosperous, had nothing.”43

Thanks to the granting of limited rations the situation had improved by 1886. But the federal government picked the rations of beef and flour more with an eye on economy and ease of transport, than on maintenance of health. In addition, the first reserve log houses were poorly ventilated with no insulation so the homes were cold in the winter.

These dwellings became breeding grounds for illnesses. Measles and influenza, and the great killer, tuberculosis, spread quickly. In the 1880s the population of the Treaty Seven area continued to decline.44 From 1884 to 1886 Crowfoot lost several of his children to tuberculosis.45

By the late spring of 1886 the Blackfoot chief had only one baby daughter at home, two daughters who were married, and a grown son who was going blind.46 In addition, in early July 1886, he lost his beloved son Poundmaker.

Some years earlier Crowfoot had adopted the young Cree, who lived with the Blackfoot for several years, before returning to his own people. Poundmaker died while on a visit to the Blackfoot Reserve shortly after his release from Stony Mountain Prison in Manitoba, where he had been incarcerated for half a year after the troubles of 1885. Poundmaker died of a lung haemorrhage, while celebrating the Sun Dance with Crowfoot.47

In conversation with the prime minister, Crowfoot “complained of the disappearance of the buffalo and the encroachments of the white race.” The Ottawa Free Press reported Macdonald’s reply: “If they were all peaceable he would see that they were well cared for.”

It was a brutal age. As social welfare historian Hugh Shewell has written, welfare relief in North America “was not a readily accepted function of the state in the middle-to-late-nineteenth century.”48 Macdonald saw no need for any additional compensation, apart from a gift of twenty five dollars to each of the chiefs. In parting Lady Macdonald gave a photo of her husband to Crowfoot. 49

The Saskatchewan party reached Ottawa on the morning of October 11. Immediately they joined the Alberta Blackfoot at an afternoon levee or reception.50 A group photo shows them on the steps of the Ottawa city hall with Mayor Francis McDougal.51 The Saskatchewan group included two important Cree chiefs — Big Child (Mistawasis), and Starblanket (Ahtahkakoop) from the Prince Albert area. They were friends and close allies.52

Both were Christians who believed that the tenets of genuine Christianity resembled those of Cree traditional spirituality. Both men had daughters married to Hudson’s Bay Company men53 and both had accepted Treaty Six in 1876, as they believed change, while neither sought nor desired, was inevitable.

In Anglican missionary John Hines’s words, Big Child “excelled all the other Indians in his enthusiasm for hymn-singing; he was too old to learn to read, but he had no difficulty in committing the words to memory, and when he sang unto the Lord, making melody in his heart.”54

Starblanket was also about seventy years old. While he had embraced Christian ways he had not lost connections with his traditional religious outlook, including a belief in the “efficacy of bear-worship.” Starblanket and his wife when ill one winter had promised the bears they would give a feast to them if they recovered.

The couple’s health returned, and, keeping to their pledge, they performed the bear ceremony the next spring in 1883. When the Anglican missionary learned of this he chastised them soundly saying that God had given humans dominion over all living creatures, while the old religion “placed man beneath the animal creation.” 55

Big Child and Starblanket travelled with Louis O’Soup, a Saulteaux (Ojibwe), from the Qu’Appelle region east of Regina. O’Soup, or Osoop, which meant literally “backfat,” was a noted orator, and a successful farmer on the Cowessess Reserve.56

A fourth man, Kahkewistahaw, meaning in Cree “he who flies around”, commonly known in English as “Flying in a Circle, ” completed the party. The tall (over six foot) Plains Cree in his mid-seventies came from the Kahkewistahaw Reserve, which was named after him, on the south side of the Qu’Appelle Valley beside Cowessess. He had taken up farming and cattle-raising.57

The Saskatchewan First Nations kept to their custom of sleeping on the floor. At home very few had chairs or used bedsteads.58 In contrast, Red Crow had owned a regular bed for sometime and knew the comfort of a mattress.59 Apparently the Alberta chiefs slept on the mattresses in their hotel rooms, but held partially to the old ways. They did not, for example, open up the hotel’s soft and clean white sheets. They slept on the bed cover and did not use a pillow for their heads at all.60

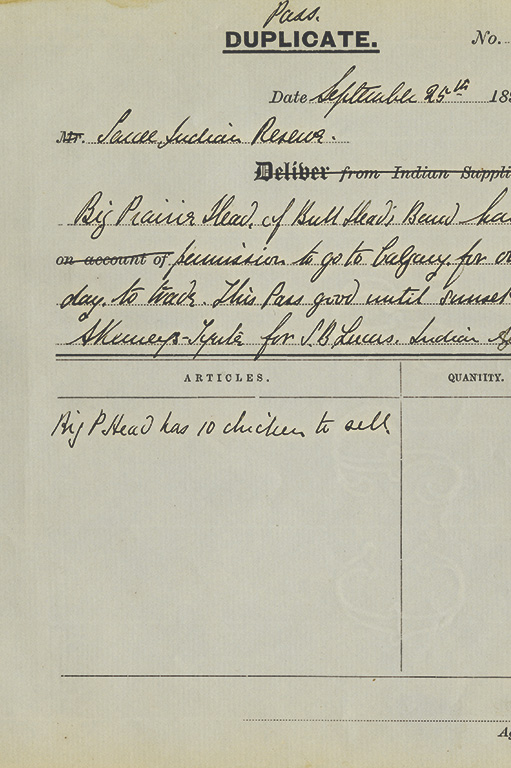

Indian agent Allan Macdonald, the son of a Hudson Bay Company fur trader and his Aboriginal wife, led the Saskatchewan party. The repressive system for controlling reserve lands and residents had begun. Amongst the Plains First Nations the agent had enormous power as he had the authority to refuse ration and to deny passes allowing people to leave the reserve.

But fortunately for the Qu’Appelle people, Macdonald was one of the more humane agents. Already local settlers had called for the surrender of portions of the Qu’Appelle Valley reserves. As a friend of the First Nations, Macdonald opposed any reduction to the Qu’Appelle people’s land base. 61 Scottish mixed-blood interpreter Peter Hourie from St. Andrew’s, Manitoba, a department employee, assisted Macdonald on the trip east.62

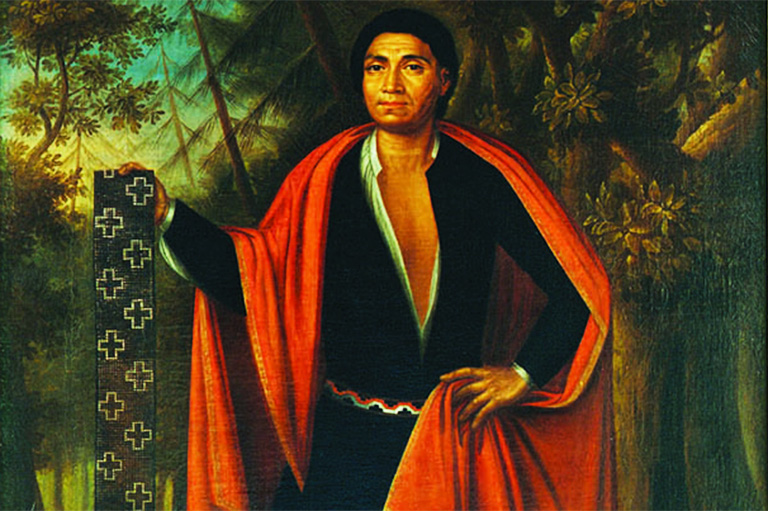

The government’s invitation to the Saskatchewan leaders included a visit to Brantford, Ontario, to view the unveiling of an impressive monument to Joseph Brant, the great Iroquois leader who fought beside Britain in the American Revolution. Late nineteenth-century Canadian politicians saw the eastern Canadian reserves as a laboratory and training ground for the “civilization” of the First Nations in the Northwest.

The Six Nations territory west of Hamilton, Ontario, was a showpiece for the Department of Indian Affairs, the best example of the “success” of the Dominion’s Indian policy. Here the number of farms and the acreage used as farmland in the 1880s were considerable.63 There was also a “respected” residential school, the Mohawk Institute, from which most of the teachers in the dozen or so day schools had graduated.

Tired and sick, Crowfoot64 and Three Bulls left the tour after the Ottawa city hall levee. The newly arrived Red Crow, One Spot, and North Axe stayed. On October 12 they travelled with the Saskatchewan chiefs to the Brantford ceremony.

The Blackfoot and Cree had a common language — Plains sign language — that allowed them to express their thoughts and emotions. The gesture for eating, for instance, was made by placing both hands toward the mouth with fingers hanging, and then alternately raising the hands and letting them fall as if to throw something into the mouth.65

On October 13 the Plains Indians joined a huge crowd of approximately 20,000,66 predominantly non-Natives, at the unveiling of the Brant monument. They stood in front of the majestic nine-foot bronze statue placed on the top of a granite pedestal. The western chiefs wore their treaty medals. As the Six Nations warriors began a war dance, the western leaders responded with their shrill plains war whoops.67

During the ceremony, “An Ode to Brant,” a poem written by a young Six Nations writer was read. The daughter of a Mohawk chief and his well-educated English wife, she was too retiring to read it herself. By the early 1890s she would conquer her initial shyness, and begin a performance career. At the turn of the century E. Pauline Johnson, also known as Tekahionwake, had become Canada’s best-known female poet and one of North America’s most notable entertainers.

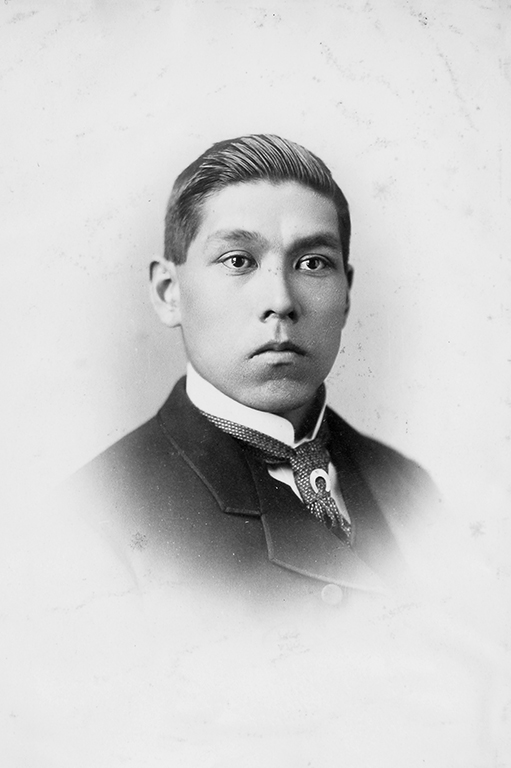

Red Crow was particularly impressed by the banquet speech that evening given in perfect English by A.G. Smith (Deh-ka-nen-ra-neh), whose Mohawk name meant “Two Rows of People.”68 Speaking in his second language, the chief caused his non-Indigenous audience to both laugh and applaud. The tall, rather slender young man had attended the Mohawk Institute. Left an orphan as a boy, he excelled at the school, then he entered Brantford High School, where he did very well. After leaving school Smith had become the Anglican Church’s Mohawk interpreter.69

On October 14 the visiting chiefs called at the Mohawk Institute itself. According to The Mush Hole: Life at Two Indian Residential Schools compiled by Elizabeth Graham, the school had a total of ninety students, including forty-five boys and forty-five girls. The Plains visitors learned that two recent female graduates had begun their careers as schoolteachers, and two male graduates had obtained work, one as a carpenter, the other as a blacksmith.70

Jessie Osborne, a teacher at the school, was herself an 1883 Mohawk Institute graduate who had made the honour roll.71 the Globe reported, “Each of the chiefs was presented with a pair of mittens made by the pupils under Miss Osborne’s charge and Red Crow was so delighted with them that he wore his on the way home.”72

Unstated was Osborne’s genealogy. Her great-great-grandparents included (by the European kinship system), Sir William Johnson, the British superintendent of Indian Affairs;73 and his consort, Molly Brant, the sister of Chief Joseph Brant; and on another branch of her maternal family, Chief Joseph Brant himself.74

Overall, as the 2015 final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has clearly established, the Indian boarding school system was a failure. Student recollections of their experiences were overwhelmingly negative. The residential schools had little parental support or involvement. They depended on military discipline and student labour.75

In respect to the Mohawk Institute, Pauline Johnson’s two brothers, Beverly and Allen, had hated their years there in the late 1860s. Allen, in fact, had run away.76 As the Johnson brothers came from a family in which English was the first language, the rule that they must “promise to give up talking Indian, till they have learnt to speak English with more ease and fluency,” did not apply. Nevertheless they still detested the institution.77 The discipline was very strict.

In April 1903, eighteen years after the chiefs’ visit, a spectacular fire left the school in ashes. Arsonists had tried before to burn down the school, but this time the attack by four students was successful. Fortunately, all the 120 or so pupils escaped the fire. The investigation revealed that those responsible “resented the strict discipline maintained at this school.”78

Fred Loft, known in Mohawk as Onondeyoh, meaning “Beautiful Mountain,” who later in 1918 became the founder of the League of Indians of Canada, the first pan-Indian organization in the country, intensely disliked the school. The Mohawk Christian boy of twelve spent an unhappy year in 1874 at the institute.

“I recall the time when working in the fields I was actually too hungry to be able to walk, let alone work,” he said later. “In winter the rooms and beds were so cold that it took half the night before I got warm enough to fall asleep.”79 His parents fully supported their son in his decision not to return.

They had always allowed him a great deal of freedom. At thirteen years of age Loft walked a dozen kilometres (eight miles) a day, round trip, to attend the public school in neighbouring Caledonia, a non-Native community. At the end of his first year, Loft lived in Caledonia, supporting himself by working for his board and lodging. Once he finished elementary school, the determined young man immediately entered high school, where he studied from 1878 to 1881.80

Another former student, Peter Martin (Oronhyatekha) — who went on to become a medical doctor — escaped at least three times in the four years he attended the Mohawk Institute in the early 1850s. To cite his biographers Keith Jamieson and Michelle A. Hamilton: “He returned each time, sometimes willingly, sometimes forcibly. Each time he received a whipping and was made to promise not to do it again.”81

Yet, at the same time, if one accepts superintendent Robert Ashton’s testimony in 1886 about the Mohawk Institute’s first fifty years, there was evidence of some academic success: “Of the past graduates of this Institution, there are at present actively engaged in their professions: two clergymen, two physicians, one civil engineer and Dominion land surveyor, two civil service clerks, seventeen school teachers, and many others have qualified as teachers but are engaged in other callings. Several are following the trades (carpenters and blacksmiths) they were taught here, whilst a large number are well-to-do farmers and wives of farmers.” 82

The Six Nations Council had considerable control over local schooling, running one of the day schools entirely itself. It also had representation on the school board established in 1878 to administer another ten or so schools for Grand River Six Nations students. Trained and qualified teachers from the Mohawk Institute staffed these schools.83

The reserve schools taught the same subjects as elsewhere in Ontario: reading and writing, arithmetic, history and geography.84 Mohawk Isaac Barefoot, an 1854 graduate of the Mohawk Institute, taught school on the reserve then gained admittance to the Toronto Normal (Teacher Training) School in 1860. Barefoot taught at the Mohawk Institute in the 1870s, and once served as the acting principal. He attended Huron College in London, Ontario and was ordained in the Church of England. The Anglican minister who was the incumbent of St. John’s and Christ Church at Six Nations served as the Inspector of the Six Nations schools in Brant County85.

If the language barrier had not existed, and the western chiefs’ visits had been longer, serious shortcomings would have come to light. Cultural loss was a serious issue. As historian Alison Norman discovered in her study of the Six Nations of the Grand River from 1899 to 1939, the cultural loss among the female students who graduated from the Mohawk Institute and became schoolteachers was considerable. She writes in her 2010 Ph.D. thesis:

“If they still spoke their native language on entering the school, many of them lost it. Students of the Institute also experienced a particular type of upbringing, removed from their family, separated from students of the opposite gender and taught that their traditional culture had little value. 86 Fortunately medical conditions at the Institute in the late nineteenth century were much better than in other Indian residential schools in Canada, from 1862 to 1897 only five deaths occurred.87

The Mohawk Institute impressed the Plains visitors. Later, when he was back home in southern Alberta, North Axe became ill, and, on the point of death, was unable to speak. By using sign language the Peigan chief gave instructions to the Indian agent to send his son and brother to the Mohawk Institute to be educated.88 Red Crow returned convinced that education could help solve his community’s problems.

While he had no school age children of his own, he supported the Methodist, Anglican, and Catholic schools on the reserve. In later years he sent Shot Close, his favourite adopted child, to be educated at the St. Joseph’s Industrial School, also known as Dunbow, about forty kilometres southeast of Calgary. The Roman Catholic school taught farming and trades to young Indians.89 Upon arrival Shot Close obtained the name in English of Frank Red Crow.90

Red Crow did not realize at the time the full consequences of this decision. Dunbow, like other Indian boarding schools, was plagued with health issues. 91 The mortality rate of the student body was high, but Shot Close managed to escape ill health. The boy learned to speak perfect English and the technical skills of farming. Historian Hugh Dempsey writes:

“True, he had kept his language, for there were other Blood and Blackfoot boys with him, but there had been constant pressures from the priests for him to cast aside his ‘heathen’ ways.” Red Crow, who was adamant that the Bloods retain their religion, realized the enormous strain on his son of the religious indoctrination, “but,” Dempsey adds, “just as warriors spent months away from home, gaining the prestige and knowledge needed to sustain them in later years so did his son need the white man’s education.”92

Frank Red Crow left Dunbow in the late 1890s, and on his return to the reserve became a prosperous rancher. He was elected as a minor chief of the reserve until he retired in the 1950s.93 In that same decade, Frank Red Crow assisted Dempsey with the research for his book Red Crow, Warrior Chief (1980).

The Blackfoot and Saskatchewan chiefs spent October 15 at Ohsweken, the Six Nations village south of Brantford. At the council house, the First Nations visitors met the hereditary Six Nations chiefs, who had been selected by clan mothers. The Globe on October 19 recorded Louis O’Soup’s reaction to the Six Nations community:

“Here the red men were equal to the white men, and more than that, he was thankful that his children would soon learn to read and write like the white men.”94 Red Crow as well left the Six Nations Territory in good spirits. He had seen First Nations people growing crops, learned many had acquired English, and discovered graduates of the residential school had obtained jobs in the trades and in teaching.95 Also, a substantial number of the Six Nations maintained their traditional religion.

The Blackfoot representatives returned to Ottawa on October 16, before departing for Alberta on October 18.96 In Ottawa, or possibly after a short stop en route in Toronto, they encountered an extraordinary phenomenon. John Maclean reported what Red Crow and North Axe told him: Their “white friends” took them to “a large trading post… into a small room which had an iron door.”

After they stepped in the door closed, the whole room moved upwards, to more rooms up above. They walked around on floor then returned to the small apartment. Once the door closed, it descended, seemingly going to the place, “where the white men say the Great Evil Spirit dwells.” Finally it stopped. The door of the elevator opened, and out they came “at the same place where they had started from.”97

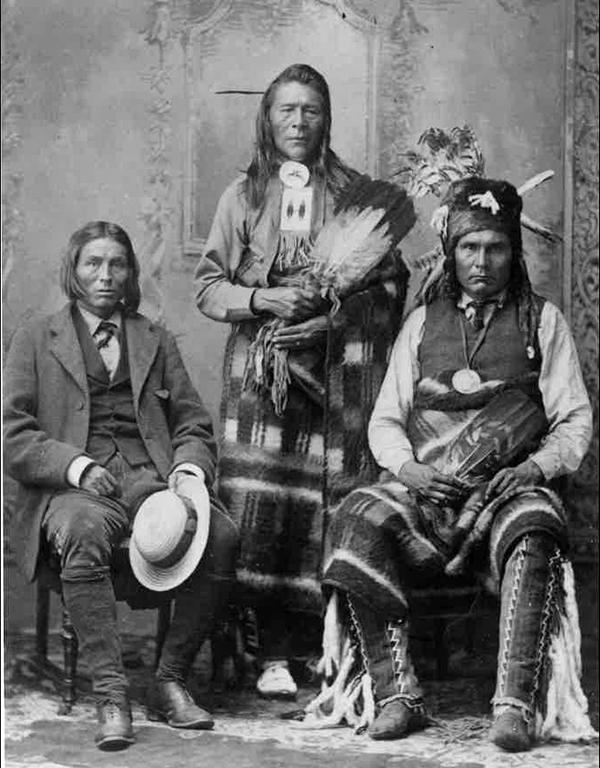

After the Brant monument ceremony, the Cree chiefs and the Saulteaux O’Soup attended the Six Nations Agricultural Society Fall Fair, founded two decades earlier by Christian Mohawk farmers.98 Afterwards they visited the neighbouring Mississauga (Ojibwe) reserve of New Credit.99 Just before they departed from Brantford, a professional photographer took a picture of L’Heureux with One Spot, Red Crow, and North Axe.100 Another shot was taken of the Saskatchewan visitors, with O’Soup and interpreter Peter Hourie.101

The Saskatchewan group left for Ottawa, via Toronto on October 21. In Toronto they called upon Alexander Morris, who had been the treaty commissioner in 1876.102 Two days later, in the early afternoon of October 23, Macdonald welcomed the Saskatchewan chiefs to Earnscliffe. 103 Starblanket in particular impressed Sir John. The two men were approximately the same age, around seventy.

Through interpreter Hourie the prime minister asked the tall (six-foot-three)104 dignified-looking Plains leader if he would give a Cree name to his 17-year old daughter. The Macdonalds were devoted to Mary, who was a victim of hydrocephalus, a debilitating disease, leading to a great enlargement of the head. She had a major speech defect, was unable to walk, and had limited use of her hands.105

Every evening on his return from work the devoted father spent an hour with his disabled daughter.106 Starblanket consented, and gave her part of his name in English. She was named “Atahk,” meaning “The Star”.107 Later that afternoon the prime minister and his First Nations visitors meet with the Privy Council, or Cabinet Secretariat, in the Parliament Buildings.

After a short visit to Montreal the Saskatchewan group departed for the West. Starblanket arrived back at his reserve in mid-November.108 By late 1886 both Starblanket and Big Child knew the relationship of mutual help and the sharing of the country were not to be. The reserve system had become a repressive system for controlling them.

They felt the intense injustice of keeping Big Bear locked up at Stony Mountain Penitentiary in Manitoba when he had not been responsible for the Frog Lake incident. He had sought to keep the peace, but he had lost control of his community. Big Bear, they both knew, wanted to use peaceful means to obtain improvements in the life of the Plains Indians.

Big Child and Starblanket both petitioned the Canadian government for Big Bear’s release particularly as others, such as Poundmaker, had been freed in early 1886. The chiefs argued that the release of Big Bear “would be very gratifying to the Cree nation.” 109 The government finally acted and released Big Bear in February 1887, but he was in poor health he died within a year.

The First Nations tour led by Methodist missionary John McDougall had left first, in early August. It was away the longest. The loyal Methodist chiefs returned to Alberta after a journey of three months in early October. McDougall’s antagonism toward the Department of Indian Affairs was well known. The Indian Act gave the department unwarranted autocratic power. It discouraged Native self-help, and self-sufficiency, as well as self-respect. Later amendments added additional paternalist and offensive features.110

In light of McDougall’s repeated protests against the Indian Act and the newly instituted pass system to restrict First Nations travel off the reserve, the government declined to fund the Methodist contingent. Nor were the Methodist visitors invited to Earnscliffe.

The three Methodist chiefs saw a great deal in Central Canada, from well-established farms with fenced fields and cattle in the countryside, to scenes of life in the large cities. McDougall worked hard for them, “to see all the objects of interest in every place we visited.”111 They travelled by rail, then by steamboat across Lakes Superior and Huron to Owen Sound. The Toronto Evening Telegram reported on August 11 that Pakan “thinks the white men’s steamboats are the most singular things he has seen.”112

From Owen Sound they departed for Toronto, Ontario’s largest city.113 At the time North American Indians made up only a minute percentage of the city’s population of approximately 100,000. Samson was entranced by the street lighting in the city, which “seemed like the stars in heaven”.114 Pakan was amazed by the buildings. The Evening Telegram reported on August 11, “He is greatly astonished at the height of the houses in the city.”115

Inevitably the visitors also had glimpses of the seamier side. Environmentally, for instance, the city was a disaster. Only two years earlier the Ontario Board of Health had reported, “Toronto Bay is a disgrace to the city…. The limpid bay of half a century ago has been converted into what is little better than a cesspool.”116 On hot days everyone in the city could smell Toronto’s sewer-like harbour.117

McDougall’s summary of their activities in southern Ontario and Quebec is impressive: “We examined the manufactories and beheld the crude material transformed into articles of use in every walk in life; saw iron cast into stoves, door locks, plows and car furnishings; saw wood made into paper covered with ‘the news of the world;’ looked at the wool as it came from the sheep and witnessed it turned into flannels and blankets; saw cotton as it grew made into prints; went to Eddy’s Mills in Hull and saw the manufacture of pails, tubs, washboards, and matches for the millions.118 The air in Hull reeked from the stench of the Eddy Match Company and the lumber mills upstream.

On Sundays the towns and cities were dead silent, apart from the pealing of church bells. John McDougall’s party consisted of Chiefs Pakan and Samson — two important Cree Methodists — and Jonas Goodstoney, a young Stoney Nakoda chief, fluent in Cree.119 McDougall interpreted for all three of them. Chief Pakan, known in English as James Seenum, had an impressive appearance, “good physique, tall, straight, and strong.” 120 He was in his mid-forties.121

McDougall praised Pakan: “He had been loyal in 1885. He had saved Canada countless money and many lives by the actions of himself and his people.”122 Pakan had followed the advice of his late minister, the late Henry B. Steinhauer, or Shawahnekizhek, the Ojibwe Methodist minister who had worked from the late 1850s to his death in 1884 to develop a self-supporting Christian mission at Whitefish and neighbouring Goodfish Lake in what is now northeastern Alberta.123 McDougall’s first wife, Abigail Steinhauer (who died in 1871), was the eldest daughter of Shawahnekizhek.124

In Berlin (present-day Kitchener) Pakan admired the immense work the citizens had made: “Yours is a wonderful Town. How many comforts and blessings you have — I am almost filled with envy — but I can see that it had taken long years to clear the forests and to pile up the stone, for I can see for myself that this has been a heavily timbered country and it has taken years of hard work for you to do what you have done. No wonder you are prosperous you have worked hard for it.”125

In Kingston, Ontario, Pakan saw pure inhumanity in the newcomers’ treatment of the incarcerated. After a tour given of the penitentiary, the Cree chief remarked: “If I ever should do anything which would bring me here, I will ask as a favour, to be killed at once, which would be better than this.”126

In Ottawa Pakan protested directly to Lawrence Vanknoughnet, the deputy superintendent of the Indian Department, against the injustice of Big Bear’s incarceration in Manitoba.127 Above all else Pakan wanted education and economic development to help his people become economically self-supporting. The Whitefish and Goodfish Cree tended crops and raised animals. They had learned to build log cabins. Instead of window glass they stretched thin wet animal hide over a window frame.

Consequently, after the demise of the great Plains buffalo herds on the Canadian side of the border in 1879, the people at Whitefish Lake could still feed themselves as they had learned how to farm.128

As did his mentor the late Shawahnekizhek, Pakan sought to bring the Native and European worlds together. “My object in going east was to get more schools for my people. Schools are what we want, to educate our children, who are thirsting for knowledge.”129 He wanted caring concerned teachers like Elizabeth Barrett, an Ontario schoolteacher who taught for two years at Whitefish Lake in the mid-1870s. She learned to speak Cree, to the delight of the children.130

McDougall had known Chief Samson, who was considerably older than Pakan, since the 1860s, when they went on buffalo hunts together. “I will never forget those wild rides beside my friend when, with a peculiar whoop and cry, he would start a herd, and then, watching the wind and lay of country, continue to manoeuvre them homewards.”131

Newspapers interested Samson. As he told a reporter, “It is very wonderful. You can tell your people in our newspapers what is going on all over the world. If anything happens in the great country over the water you have it in your paper; but the poor Cree knows nothing of the world or what is in it.” 132

The telephone, invented a decade earlier, was the greatest surprise. The Hamilton Spectator noted August 20, “Two of them talked over the wires in the central offices in Toronto, and half the time they could not speak for laughing.”

However, the crowds that collected when they appeared aggravated Samson. The visitors were curiosities and people thronged the streets trying to get a glimpse of them.

As Samson told a reporter in London, Ontario, their curious gazes were annoying; “We like to see the great streets of your cities, and your factories, but what makes us hurry back to our hotel rooms is the way you people look at us. If we go along the street men and women stop to stare at us, and your children gather around and look into our faces and make remarks and laugh. We don’t like that.”133

McDougall worked with host churches134 to pay the travelling expenses incurred through collections at talks by the loyal chiefs.135 “Nightly, and sometimes twice on Sunday, the Indians addressed thousands of their fellow citizens”.136 In McDougall’s words, “we visited most of the cities and towns between Sarnia and Montreal.” The “loyal chiefs” attracted huge crowds in the metropolitan centres.137

In many cities in southern Ontario there had been little contact between Indigenous people and non-Aboriginal Canadians for at least two generations. The chiefs were most likely the only Native persons that many in their audiences had ever seen or heard speak. The Evening Telegram commented two years earlier:

“It is not so long ago that the whole country was inhabited by Indians. Where Toronto now stands was a forest with Indian wigwams scattered along the lake shore. The Indians have made way for a superior race.”138 The quote illustrates the non-Indigenous Canadians assumption of superiority.

In another example of racial thinking, the Toronto Mail, one of Canada’s largest circulation newspapers, published a story entitled, “The Condition of the Indians” on February 3, 1886:

“Science, which excludes Christian morals from its code, tells us that the annihilation of the savage is decreed and carried out by the operation of a law ordaining the survival of the fittest; and that the drunkenness, debauchery, and disease which attack him simultaneously with our appearance are merely the instruments which nature employs in the execution of her remorseless purpose.”

McDougall had invited Jonas Goodstoney, “a representative young man, who is fast adopting civilized habits and ideas,” as the third member of the Methodist group. 139 In the spring of 1885 Goodstoney had been one of several Stoney scouts who rode with McDougall in advance of the Alberta Field Force from Calgary to Edmonton.140

Recently Jonas had begun to farm, with cattle and horses.141 Before he left home he had marketed some new potatoes.142 Unlike Pakan and Samson, who appeared in Native dress, the Goodstoney wore a dark tweed coat, vest, and knickbockers.143

During their tour the Methodist chiefs were sometimes accompanied by Robert Steinhauer, a young Cree from Pakan’s community who was then completing his fourth and final year at Victoria College in Cobourg, Ontario. Steinhauer was McDougall’s brother-in-law — the late Abigail Steinhauer was his sister. In September 1886, Steinhauer accompanied McDougall and the Methodist chiefs to several Ontario towns and cities, as well as Montreal.144

John A. Macdonald met Robert and the Loyal Methodist Chiefs during a surprise visit to the Metropolitan Church in Toronto during meetings of the national Methodist General Conference. Robert sang the hymn, “Tell it Again,” before the prime minister, with Chief Pakan joining in by singing it in Cree.145 Although Macdonald did not realize it, he had before him, in Robert Steinhauer, one of his most articulate First Nations critics.

In the spring of 1886 the undergraduate had written an article for Acta Victoriana, the Victoria College magazine. In “The Indian Question” he complained that the treaty promises of the mid-1870s had not been fulfilled.

“Ever since the treaties were signed, there has been much discontent, and complaints made by him [the Indian]. He asks those who have taken the ownership of his country to give him his rights, at least the fulfilment of the promises made to him.” They had wanted assistance, but, in the place of competent government intermediaries, Ottawa selected agents, “because they happen to be friends and right-hand supporters of the Government in power.”

The Indian Department had placed “low and unprincipled characters”146 over them, the article stated.

By November all three groups had returned home. The chiefs had varying experiences in Canada. The tour proved an ordeal for Crowfoot who returned ill and tired. The robust Starblanket, in contrast, came back to his community in good health and spirits.147 Red Crow, One Spot, and North Axe had a celebration when their tour neared its end. By the time they got to Lethbridge, the last “white man’s town” on their itinerary, their impassive façade, the public reserve shown to the Central Canadians, vanished.

As historian Dempsey writes: “They cast aside all the stoicism of the previous days, wiping out all the tensions and strangeness of the white man’s world, and relaxed within sight of the familiar Rocky Mountains.”148

Pakan came back to his community profoundly disappointed. In Ottawa he had wanted the federal government to commit to the fulfillment of its treaty promises. The Cree chief had left in early August with great optimism. He sought equality, not the status of sub-citizens accorded them by the Indian Act.

In Ottawa he had informed Vanknoughnet, that their reserve lands, “should be considered as the Private property of the Band,” beyond the Indian agent’s control. He opposed the permit system that prevented band members from selling any portion of their crop or livestock without permission. He said the Cree must themselves control the sale of their hay and crops, and their cattle.149

For a people who had formerly travelled freely over a vast country it was humiliating and degrading to have to ask for permits to sell their own produce, and to ask for a pass to leave their reserve.

The Canadians, however, refused equality. Peter Erasmus, the Métis interpreter, later reported Pakan as saying that “promises by government people were like the clouds, always changing.”150 Instead of more liberty the word “control” coupled with financial restraint now dominated relations with the government.

Another incredible disappointment followed. The promise of Indian education was not meet. The schools were conceived, designed and run almost entirely by non-Indigenous people. The First Nations had no control over the boarding schools. Indian language and culture were suppressed.

Parents must send their children away to poorly funded institutions ruled by a harsh discipline totally contrary to Indigenous teachings. In the summer of 1893 Pakan had helped to bring seventeen students from Whitefish Lake to the Methodists’ new Red Deer Industrial School.151 After only one year Pakan asked for the return of his son.152

What the Indian Department thought the Indians were agreeing to, and what the Indian knew he was willing to accept, rarely coincided. As the perceptive Rev. John Maclean commented in his 1889 book, The Indians Their Manners and Customs, “We wish to make them white men,” but the Indians themselves “desire them to become better Indians.”153

Footnotes

1 M.C. Urquhart and K.A.H. Buckley, eds, Historical Statistics of Canada (Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada, 1965), p. 14. See: Series A2–14. Population of Canada, by province, census dates, l851 to l961. For the Plains First Nations population in the early 1890s see, James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains. Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life (Regina: University of Regina Press, 2013), 172.

2 T.D. Green to The Rt Hon Sir John A. Macdonald, dated Indian Office Regina, 8 March 1886, Macdonald Papers, MG 26A, vol. 424, p. 206289, microfilm C–1775, LAC.

3 Jack Dunn, The Alberta Field Force of 1885 (Calgary: Jack Dunn, 1994), 79.

4 George Ham, “Among the Bloods. Rev. John Macdougall on the Indians and Their Grievances,” Toronto Mail, 30 January 1886, p. 4. My thanks to Hugh Dempsey for showing me his photocopies of all of Ham’s Daily Mail articles on the North West in early 1886, 5 January to 6 March.

5 Emma LaRocque, When the Other is Me. Native Resistance Discourse 1850–1990 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2010), 83.

6 Hugh A. Dempsey, Crowfoot, Chief of the Blackfeet (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1972), 202

7 Hugh A. Dempsey, “Jean L’Heureux,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14: 1911–1920 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998), 652–654.

8 Raymond Huel, “Albert LaCombe,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14: 1911–1920 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998), 573–577.

9 Hugh A. Dempsey, The Great Blackfoot Treaties (Victoria, B.C.: Heritage House Publishing Company, 2015), 175.

10 D’Arcy Jenish, Indian Fall. The Last Great Days of the Plains Cree and the Blackfoot Confederacy (Toronto: Penguin Books, 2000), 293. John C. Ewers writes; “ A normal day’s march was about ten to fifteen miles,” see: The Blackfeet. Raiders on the Northwestern Plains (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1958), 94

11 Walter McClintock, The Old North Trail, or Life, Legends and Religion of the Blackfeet Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1968; first published, 1910), 13.

12 J. William Brennan, Regina. An Illustrated History (Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 1989), 18.

13 Dempsey, Crowfoot, 25. Hugh A. Dempsey, Red Crow, Warrior Chief (Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1980), 142–143.

14 George H. Ham, Reminiscences of a Raconteur, 116; quoted in Dempsey, Red Crow, 142.

15 Alan Artibise, Winnipeg. An Illustrated History(Toronto: James Lorimer & Compnay, 1977), 202.

16 Robert Prévost, Montréal. A History. Translated by Elizabeth Mueller and Robert Chodos (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1993), 311. According to the 1891 census Montreal had a population of roughly 215,000, compared to Quebec City’s 63,000, and Toronto’s 180,000,

17 Allan R. Taylor, “Note Concerning Lakota Sioux Terms for White and Negro,” Plains Anthropologist, 21 (1976), no. 71, page 64.

18 I thank Hugh and Pauline Dempsey for this information, 10 March 2017.

19 Dempsey, Crowfoot, 25.

20 Ibid, 148.

21 Crowfoot as translated by the reserve interpreter in, George Ham, “The Blackfeet Chief. An Interesting Conversation with the Renowned Crowfoot. Dated Blackfoot Crossing, N.W.T. 26 Jan.,” Toronto Daily Mail, 3 February 1886. My thanks to Hugh Dempsey for showing me his photocopies of all of Ham’s Daily Mail articles on the North West in early 1886, from 5 January to 6 March.

22 Dempsey, Crowfoot, 202–203.

23 Dempsey, “he Fearsome Fire Wagon,” in The CPR West, ed. Hugh A. Dempsey Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre 1984), 64.

24 George Bird Grinnell, Blackfoot Lodge Tales. The Story of a Prairie People (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press 1962), 219. The classic first appeared in 1892.

25 John McLean [Maclean], The Indians of Canada. Their Manners & Customs (Toronto: William Briggs, 1889), 79.

26 Rev. John McLean [Maclean] M.A., Blood Reserve Alberta Canada,” “The Blackfoot Indian Confederacy” (Ph.D. thesis, Illinois Wesleyan University, Bloomington, Illinois, 1888), page 139, Record Group 13–3/2: Non-Resident Theses. Tate Archives & Special Collections, The Ames Library, Illinois Wesleyan University Bloomington, Illinois. I thank Meg Miner, University Archivist and Special Collection Librarian, for her invaluable assistance in sending me a scan of the thesis.

27 Hugh A. Dempsey, Charcoal’s World (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1978), 9.

28 Dempsey, Red Crow, 169.

29 “Local News,” Toronto Globe, 2 September 1886.

30 “Crowfoot at the Bazaar,” Montreal Daily Star, 30 September 1886.

31 Dempsey, Crowfoot, 215.

32 “Crowfoot at the Bazaar,” Montreal Daily Star, 30 September 1886.

33 François Ricard, “Honoré Beaugrand,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13: 1901–1910 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994), 51–53.

34 “Bazar de la Cathédrale,” La Minerve, 30 septembre 1886.

35 Dempsey, Red Crow, 164.

36 Dempsey, Crowfoot, 203.

37 Kenneth Munro, “John Jones Ross,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13: 1901–1910 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994), 900–904.

38 Michel Lessard, The Livernois Photographers (Quebec City: Musée du Québec-Québec Agenda, 1987), 169. The catalogue numbers for the images in the Glenbow Museum Archives in Calgary are; Crowfoot, Lacombe and Three Bulls, NA–1654–1; Crowfoot, NA–182–1 and NA–182–2. “Pied de Corbeau,” Le Canadien (Montréal), 5 octobre 1886.

39 Dempsey, Crowfoot, 203.

40 Glenbow Archives/ NA–13–2; also National Archives of Canada/ PA 45666

41 A good overview of Earnscliffe appears in Norman Reddaway, Earnscliffe. Home of Canada’s first Prime Minister and since 1930 Residences of High Commissioners for the United Kingdom in Canada (London: Commonwealth Relations Office, 1955).

42 “A Peaceful Pow-Wow. The Indian Chiefs Visit the Premier and Lady Macdonald—Crowfoot’s Speech,” Montreal Daily Herald, 11 October 1886.

43 Edgar Dewdney to John A. Macdonald, Superintendent-General of Indian Affairs, 2 January 1880, quoted in A.J. Looy, “The Indian Agent and his Role in the Administration of the North-West Superintendency, 1876–1893” (Ph.D. thesis, Queen’s University, 1977), 143.

44 The Glenbow Museum, The Blackfoot Gallery Committee, Nitsitapiisinni. The Story of the Blackfoot People (Toronto: Key Porter Books, 2001), 69. G. Graham-Cumming, “Health of the Original Canadians, 1867–1967,” Medical Services Journal of Canada, 23,2 (1967): 118–119.

45 See image and also the caption for the photo in Dempsey, Crowfoot, 181. Not all the children were Crowfoot’s own, personal communication, Hugh Dempsey, 4 July 2017.

46 Dempsey, Crowfoot, 199.

47 Ibid, 200.

48 Hugh Shewell, “Enough to Keep Them Alive.” Indian Welfare in Canada, 1873–1965 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), 30.

49 “Our Indian Visitors. The Great Blackfoot Chief and His First Lieutenant,” Ottawa Free Press, 9 October 1886.

50 “Crowfoot and Comrades. A Reception Tendered Them at the Ottawa City Hall,” Toronto Globe, 12 October 1886.

51 The catalogue number for the photo in the Glenbow Museum Archives is NA–1542–1.

52 Deanna Christenson, Ahtahkakoop. The Epic Account of a Plains Cree Head Chief, His People, and Their Struggle for Survival, 1816–1896(Shell Lake, Sask.: Ahtahkakoop Publishing, 2000), 76.

53 Christenson, Ahtahkakoop, 136. Ahtahkakoop’s daughter had married Edward Genereux, who worked at Fort Carlton during the 1860s. One of Mistawasis daughters married James Dreaver from the Orkney Islands. Dreaver was eighteen when he arrived in the North West to work at Fort Carlton (p. 734, endnote 32).

54 Rev. J. Hines, The Red Indians of the Plains. Thirty-Years’ Missionary Experience in the Saskatchewan (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1915),

55 John Hines quoted in Christenson, Ahtahkakoop, 448.

56 Sarah Carter, “Louis O’Soup,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14: 1911–1920 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998), 806. Robert Alexander Innes, Elder Brother and the Law of the People. Contemporary Kinship and Cowesssess First Nation (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2013), 91–107.

57 Sarah A. Carter, “Ka-kiwistahaw,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13: 1901–1910 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994), 536.

58 Christenson, Ahtahkakoop, 558, 572. This is a wonderful book that deserves to be better known. Deanna Christensen, a former Moose Jaw Times-Herald reporter, brought to her historical study an unusual ability to identify and vividly recount important stories and events. She used oral histories as well as contemporary letters and documents.

59 Dempsey, Red Crow, 167.

60 “The Chiefs Arrive from Quebec,” Montreal Daily Herald, 7 October 1886. “Le Rev. P. Lacombe et les Chefs sauvages,” Le Manitoba, 21 octobre 1886. George Ham, “Among the Bloods. “ ‘The Mail’ Correspondent had a Long Talk with Red Crow,” Toronto Daily Mail, 28 January 1886.

61 Sarah Carter, “Allan Macdonald,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13: 1901–1910 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994), 623.

62 Sarah Carter, Lost Harvest. Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990), 120.

63 Sally M. Weaver, “The Iroquois: The Grand River Reserve in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, 1875–1945,” in Aboriginal Ontario: Historical Perspectives on the First Nations (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1994), 223.

64 Dempsey, Red Crow, 167. Christensen, Ahtahkakoop, 565.

65 John Maclean, Canadian Savage Folk. The Native Tribes of Canada (Toronto: William Briggs, 1896), 494.

66 “The Brant Memorial,” Toronto Globe, 14 October 1886.

67 Dempsey, Red Crow, 168.

68 David Boyle, “The Pagan Iroquois” in Archaeological Report 1898 Being Part of the Appendix to the Report of the Minister of Education Ontario (Toronto: Warwick Bros & Rutter, 1898), plate X1.

69 Horatio Hale, “An Iroquois Condoling Council,” Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, section II, 1895; reprinted in The Iroquois Book of Rites and Hale on the Iroquois (Ohsweken, Ontario: Iroqrafts, 1989), 49.

70 Christensen, Ahtahkakoop, 568.

71 The Mush Hole Life at Two Indian Residential Schools, compiled by Elizabeth Graham (Waterloo, Ontario: Heffle Publishing, 1997), 87.

72 “The Brant Memorial. The North-West Chiefs visit an Industrial Institution,” Toronto Globe, 15 October 1886, page 1. I thank Hugh Dempsey for telling me of this article.

73 For the enormous significance of Sir William Johnson in British North America, see J.R. Miller, Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007), 66–73.

74 By the custom of the Six Nations descent was traced in the woman’s line, the children being of the clan of their mother and not of their father. Canadian law did not recognize this system, and, from the mid-nineteenth century to the late twentieth, it traced Indian legal status in the man’s line. As Jessie’s father, the Hamilton merchant John Osborne, was non-Indigenous, she would not have been legally recognized as a Mohawk. Her acceptance into the Mohawk Institute must have been a special case. Certainly the young woman had an extraordinary family background as the descendant of Sir William Johnson, and Molly Brant. On another branch of her maternal family, she was also a direct descendant of Molly Brant’s famous brother Joseph Brant. Edward Marion Chadwick, Ontario Families: Genealogies of United Empire Loyalist and other Pioneer Families of Upper Canada (1894, reprinted Lambertville, New Jersey, Hunterdon House, 1970), 72–73. In collaboration, “William Johnson Kerr,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7: 1836–1850 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988), 466. Gretchen Green, “Molly Brant, Catharine Brant, and Their Daughters: A Study in Colonial Acculturation,” Ontario History, 81 (1989), 246.

75 This is a huge topic, for an overview see: Canada’s Residential Schools; The History, Part 1. Origins to 1939. The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, vol. one (Montreal and Kingston: Published for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission by McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015).

76 Charlotte Gray, Flint & Feather. The Life and Times of E. Pauline Johnson, Tekahionwake (Toronto: HarperCollins Canada, 2002), 49–52.

77 See the column, “Boys School July 1st to December 31st, 1868,” in The Mush Hole, comp. Graham, 217. The Johnson family, Beverly, Eva, Allen and Pauline were Indian by law. Their father was Mohawk, but their mother was English.

78 The Mush Hole, comp. Graham, 100–104, the quote by Martin Benson, clerk of the Indian Schools, Department of Indian Affairs, appears on page 103. Three of the convicted arsonists were sent to the Mimico Industrial School, and the other to the Kingston Penitentiary (page 104). Gordon Smith, the Superintendent of the Six Nations, stated on 8 October 1908 “that former pupils of the Mohawk Institute are reluctant to send their own children there because they consider the discipline is too strict.” See: W.F. Webster upon his visit to the Mohawk Institute, Brantford, and the Grand River Reserve Canada, October 1908 (London: Spottiswoode & Co., October 1908), 13.

79 Fred Loft quoted in Canada’s Residential Schools; The History, Part 1. Origins to 1939. The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, vol. one (Montreal and Kingston: Published for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission by McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015), 176.

80 Donald B. Smith, “Frederick Ogilvie Loft,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography

81 Keith Jamieson and Michelle A. Hamilton, Dr. Oronhyatekha, Security, Justice, and Equality (Toronto: Dundurn, 2016), 52.

82 In 1886, Robert Ashton, Superintendent Ashton is quoted in Graham, compiler, The Mush Hole, 87.

83 Abate Wori Abate, “Iroquois Control of Iroquois Education: A Case Study of the Iroquois of the Grand River Valley in Ontario, Canada,” (Ph.D. (Education), University of Toronto, 1984), 122,137

84 Sally M. Weaver, “The Iroquois: The Grand River Reserve in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, 1875–1945,” in Aboriginal Ontario. Historical Perspectives on the First Nations (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1994), 225.

85 Canada’s Residential Schools; The History, Part 1. Origins to 1939. The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, vol. one (Montreal and Kingston: Published for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission by McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015), 730–731. Graham, compiler, The Mush Hole, 87, 219. He graduated from the school in 1854. Toronto Normal School. Jubilee Celebration. 1847–1897. Biographical Sketches and Names of Successful Students 1847 to 1875(Toronto: Warwick Bro’s & Rutter, 1898), 137.

86 Alison Elizabeth Norman, “Race, Gender and Colonialism: Public Life among the Six Nations of Grand River, 1899–1939” (Ph.D. thesis, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, 2010), 69.

87 The Mush Hole, comp. Graham, 97.

88 John Maclean, Canadian Savage Folk. The Native Tribes of Canada (Toronto: William Briggs, 1896), 491.

89 Joe Dion, a former Cree student, retained some positive memories of the school. He later wrote, it “became one of the greatest institutions of its time and it turned out many really good men and women during its short span of activity.” Joe Dion, My Tribe, the Crees(Calgary: Glenbow Museum, 1979), 157. On Dunbow see D.J. Hall, From Treaties to Reserves, the Federal Government and Native Peoples in Territorial Alberta, 1870–1905 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015), 212,221–222.

90 Dempsey, Red Crow, 172, 196–197.

91 Brian Titley, “Dunbow Indian Industrial School: An Oblate Experiment in Education,” Etudes Oblates de l’Ouest/ Western Oblate Studies, 2 (1992): 105.

92 Dempsey, Red Crow, 203–204.

93 Ibid, 216,

94 Louis O’Soup’s remarks, reported in “Six Nations Council,” Toronto Globe, 19 October 1886.

95 Dempsey, Red Crow, 172.

96 Ibid, 170.

97 John McLean [Maclean], The Indians of Canada Their Manners and Their Customs (Toronto: William Briggs, 1889), 79.

98 Sally M. Weaver, “The Iroquois: The Grand River Reserve in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, 1875–1945,” in Aboriginal Ontario. Historical Perspectives on the First Nations(Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1994), 220.

99 A. McDonald, Indian Agent, Crooked Lake, 26 November 1886 (copy), R.G. 10, vol. 8618, file 1/1–15–2–2, Library and Archives Canada

100 Glenbow Museum Archives/ NA–2968–4.

101 Library and Archives Canada/ C–019258. Christensen, Ahtahkakoop, 571. Sarah Carter, Lost Harvest. Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990), 120.

102 Robert J. Talbot, Negotiating the Numbered Treaties. An Intellectual & Political Biography of Alexander Morris (Saskatoon: Purich Publishing Limited, 2009), 165.

103 “Indian Chiefs. They Interview Sir John Macdonald and the Other Ministers,” Ottawa Free Press, 23 October 1886.

104 “Indian Chiefs. They Interview Sir John Macdonald and the Other Ministers,” Ottawa Free Press, 23 October 1886.

105 Cyril Greenland and John D. Griffin, “The Honorable Mary Macdonald: a lesson in attitude,” Canadian Medical Association Journal, vol. 125. 1 August 1981, p. 306. I thank Allan Sherwin for bringing this article to my attention.

106 Norman Reddaway, Earnscliffe. Home of Canada’s first Prime Minister and since 1930 Residences of High Commissioners for the United Kingdom in Canada (London: Commonwealth Relations Office, 1955), 21.

107 Edward Ahenakew, “The Story of the Ahenakews,” ed. by Ruth Matheson Buck, Saskatchewan History, 27,1 (Winter 1964), 17.

108 Christenson, Ahtahkakoop, 580.

109 J.R. Miller, Big Bear (Mistahimusqua) (Toronto: ECW Press, 1996), 124.

110 Sarah Carter, “Controlling Indian Movement: The Pass System,” NeWest Review, May 1985, 8–9. F. Laurie Barron, “The Indian Pass System in the Canadian West, 1882–1935,” Prairie Forum, 13,1 (Spring 1988), 25–42.

111 “Rev. John McDougall, dated Morley, Alberta, 27 November 1886,” Calgary Tribune, 3 December 1886.

112 “Surprised Indians,” Toronto Evening Telegram, 11 August 1886.

113Careless, Toronto, 201, gives the population of Toronto as 86,415 in 1881, and 181,206, in 1891.

114 Samson quoted (translated by John McDougall) in “Three Western Indians,” Toronto Globe, 8 August 1886.

115 “Surprised Indians,” Toronto Evening Telegram, 11 August 1886.

116 Ontario Board of Health, Annual Report, 1884, 98; quoted in Gregory A. Kealey, Hogtown. Working Class Toronto as the Turn of the Century (Toronto: New Hogtown Press, 1974), 24.

117 Desmond Morton, “The Crusading Mayor Howland,” Horizon Canada, 2, 23 (1985), 550.

118 “Rev. John McDougall, dated Morley, Alberta, 27 November 1886,” Calgary Tribune, 3 December 1886.

119 Personal communication, Ian Getty, recently retired (2016) Research Director for the Stoney Tribal Administrator, 21 March 2017. Jonas Goodstoney had just become a chief.

120 O. German, “Pukan,” The Missionary Outlook, 6,7 (July 1886), 90.

121 “Three Western Indians,” Toronto Globe, 8 August 1886.

122 John McDougall, Letter from Toronto, dated 12 May 1905, Missionary Bulletin, 2,4 (June 1905): 848–849.

123 Very useful is Melvin Steinhauer’s volume, Shawahnekizhek. Henry Bird Steinhauer: Child of Two Cultures(Edmonton: Priority Printing Ltd., 2015), frontispiece, 7, 81, 84, 108. The author, a great-grandson of Henry B. Steinhauer, writes (p. 41): “When Henry Bird Steinhauer asked his fellow Indians to follow Christ, he did not want to destroy their way of life or all of their religious beliefs. Instead, he pointed out similarities between Cree religious beliefs and Christianity.”

124 James Ernest Nix, Mission among the Buffalo. The Labours of the Reverends George M. and John C. McDougall in the Canadian Northwest, 1860–1876 (Toronto: Ryerson, 1960), 34.

125 John McDougall translating Pakan’s remarks, “Visit of Indian Chiefs,” Berlin Daily News, 11 September 1886.

126 John McDougall citing Pakan, “Rev. John McDougall, Morley 27 November 1886” Calgary Tribune, 3 December 1886.

127 “Departmental and Other Notes,” Ottawa Citizen, 30 September 1886. “News of the Day,” Toronto Globe, 1 October 1886.

128 Steinhauer, Shawahnekizhek, 51–54.

129 Pakan’s remarks, translated by John McDougall, “Missionary Meeting,” Regina Leader, 19 October 1886.

130 Donald B. Smith, Mississauga Portraits. Ojibwe Voices from Nineteenth-Century Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013), 261–264. Pakan recalled her work in Regina in mid-October 1886; “She came to teach school on our reserve. We often talk about her in our camps and about the good she did for us. Our children love her for all the act of kindness she did for them, and our women looked upon her with affection”. Pakan’s remarks, translated by John McDougall, “Missionary Meeting,” Regina Leader, 19 October 1886.

131 McDougall, In the Days of the Red River Rebellion, 94.

132 Samson translated by John McDougall, “The Poor Cree,” London Daily Free Press, 6 September 1886.

133 Samson translated by John McDougall, “The Poor Cree,” London Daily Free Press, 6 September 1886.

134 “Rev. John McDougall, dated Morley, Alberta, 27 November 1886,” Calgary Tribune, 3 December 1886. I thank Hugh Dempsey for this reference.

135 “Pakan and Samson. Enthusiastic Reception at Elm Street Church,” Toronto Mail, 18 August 1886. “Visit of Indian Chiefs,” Berlin Daily News, 11 September 1886. “The Indian Braves,” Port Hope Weekly Guide, 24 September 1886. “Loyal Indian Chiefs,” The Daily Review (Peterborough, Ontario), 24 September 1886.

136 “Rev. John McDougall, dated Morley, Alberta, 27 November 1886,” Calgary Tribune, 3 December 1886.

137 “Rev. John McDougall,” Calgary Tribune, 3 December 1886.

138 Saturday, July 4, 1884,” Toronto Evening Telegram, 5 July 1884; cited in Victoria Jane Freeman, “ ‘Toronto Has No History!’ Indigeneity, Settler Colonialism and Historical Memory in Canada’s Largest City” (Ph. D., University of Toronto, 2010), 163–164.

139 John McDougall, “Letter to the Editor, dated Morley, 27 November 1886, Calgary Tribune, 3 December 1886.

140 “Three Western Indians,” Toronto Globe, 11 August 1886.

141 “Our Indian Visitors,” Toronto Daily Mail, 19 August 1886.

142 Maclean, McDougall, 164.

143 “A Council of Braves,” British Whig (Kingston), 25 August 1886. “Three Loyal Chiefs,” Belleville Intelligencer, 2 September 1886.

144The college magazine, Acta Victoriana, 10,1 (1886/87), p. 15, mentions that during the visit “Bob” visited: “... most of the important towns and cities between Montreal and Sarnia. He was well received everywhere, but no place more heartily than in Cobourg, where he is best known. He delighted the people with his singing and speaking.”

145 “Missionary Meeting,” Toronto Mail, 8 September 1886.

146 R.B. Steinhauer, “The Indian Question”, Acta Victoriana, 9,6 (March 1886), pp. 5–6.

147 Rev. John Hines, Asissipi Journal, June 2—November 15, 1886, postscript dated 20 November 1886, cited in Christensen, Ahtahkakoop, 581.

148 Dempsey, Red Crow, 171.

149 Memorandum, 7 January 1887, Deputy Superintendent General’s Letterbooks, RG 10, vol. 1092, 453, microfilm reel C–7219, Library and Archives Canada. “Our Loyal Indians. Interviewing Deputy Minister of Indian Affairs This Afternoon,” Ottawa Free Press, 29 September 1886.

150 Peter Erasmus, as told to Henry Thompson, Buffalo Days and Nights (Calgary: Fifth House, 1999), 270.

151 John McDougall, “A Midsummer Trip Among Our Missions in the North,” The Missionary Outlook, March 1894, 36.

152 J. Nelson to Indian Commissioner, 14 August 1894, RG 10, vol. 3920, file 116, 818, Library and Archives Canada, cited in Uta Hildamarie Fox, “The Failure of the Red Deer Industrial School” (M.A. thesis, University of Calgary, 1993), 54. Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, vol. 1. The History, Part 1. Origins to 1939 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015), 265.

153 John Maclean, Canadian Savage Folk. The Native Tribes of Canada(Toronto: William Briggs, 1896), 543.

.jpg?ext=.jpg)