The Battle for February 2

On February 3, 1900, British Columbia’s Cascade Record newspaper noted that “Yesterday was ‘bear’ or ‘groundhog’ day.” The newspaper’s phrasing spoke to a general indecision among Canadians in that era, torn between celebrating the majestic bruin we had long counted on to foretell the weather for the remainder of the winter or an upstart rodent from the United States. Spoiler alert — the groundhog won out. But just think of how close we came to celebrating Bear Day.

The roots of Groundhog Day lie in medieval Europe, where the Roman Catholic feast of Candlemas on February 2 was associated with winter’s midpoint. “Half your wood and half your hay/ Should be left on Candlemas Day,” went one saying.

Folk wisdom also held that good weather on that day foretold bad weather for the rest of the winter: “If Candlemas Day be bright and clear/ We’ll have two winters in the year.” A tradition developed that if a hibernating animal — a badger, bear, fox, or marmot, depending on where you were — emerged on February 2 and saw its shadow, it would retreat to its den, and winter would last four or six more weeks.

When Europeans came to North America, they brought this bit of folklore with them. In Canada, the bear became the animal of choice for Candlemas predictions. Its qualifications were impeccable: a famed hibernator, it ranged widely and in large numbers across the country, and its size made it both easy to observe and worth keeping an eye on. Nineteenth-century newspapers occasionally mentioned its prognosticatory power.

“What child is not told,” asked the Toronto Globe in 1897, “about the brown bear emerging from his lair on the fateful 2nd of February….” It is worth noting, though, that this was the Globe’s first-ever reference to the folk wisdom and that the article containing it appeared in June. The bear’s February activity was not yet regularly considered February-newsworthy.

But to the south, a rodent was rising. When the Pennsylvania Dutch — actually German-speakers, “Dutch” being a corruption of “Deutsch” — arrived in America in the 1700s they adapted the February 2 custom using the European marmot’s local cousin, the groundhog (a.k.a. woodchuck).

The term “Ground-hog Day” first appeared in mid-1800s America. Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, was hosting celebrations under that name by the 1880s, and by the end of the nineteenth century Groundhog Day was celebrated, if that is the correct word, throughout the United States.

When Canadian newspapers began around the turn of the nineteenth century to draw annual attention to the February 2 lore, there was no similar consistency regarding which animal they cited. At first, a majority favoured the bear.

In late February 1896, Quebec’s Sherbrooke Examiner published “Candlemas Bear” by an Ontario writer: “Who, as oft has been related/ Hastened back into his lair/ After he had seen his shadow/ Cast amid the solar glare,” went the poem in part. Newspapers on the Prairies were particularly pro-bear, but many in southern Ontario and British Columbia — and thus perhaps closer to American influence — settled on the groundhog straightaway.

Still other publications swung from one animal to the other. Ontario’s Newmarket Era wrote about the bear regularly each February 2 until 1904, strayed to the groundhog for a single year, and then returned to the bear.

In similar fashion, Private Fred Young of London, Ontario, would write from the trenches of France in 1916, without noting any incongruity, “This is ‘groundhog’ day in the land of our ‘Lady of the Snows.’ [And] the query as to whether the bear saw his shadow in Canada rose to our lips.”

The confusion stemmed in part from the fact that few Canadians knew how the February 2 tradition came to be, and so they had no idea whether one animal was to be preferred. While some journalists recounted the custom’s European roots, others said it was Indigenous or French-Canadian in origin.

And, because it was seldom mentioned or remembered that Groundhog Day was an American invention, Canadian newspapers rarely suggested that it might be our patriotic duty to prefer the bear. The Ledge of New Denver in B.C.’s Slocan Valley was an exception when in 1904 it grumbled, “February 2nd was Groundhog Day in old Missouri. In the Slocan it was Tuesday. The bear saw its shadow.”

But the Canadian bear slowly succumbed to the creeping conformity of the American groundhog. In a familiar cultural pattern, Canadian readers were inundated with the American version. American syndicated children’s columns such as “Burgess Bedtime Stories” taught Canadian children and parents alike the story of the groundhog’s big day.

It was the groundhog, not the bear, that was the subject of cartoons and jokes reprinted from sources in the United States. “‘People may ridicule the groundhog theory as much as they like,’ remarked an old fellow yesterday. ‘All the same, there’s truth in it,’” the Liberal of Richmond Hill, Ontario, reported in an article borrowed from the Philadelphia Bulletin.

Moreover, while there is no evidence that the groundhog possesses forecasting ability superior to the bear’s, the groundhog did enjoy other natural advantages during the day’s evolution from a folk observation of creatures in the wild to a manufactured urban event.

The groundhog was portable: You could put it in a cage, carry it to a podium, raise it to your shoulder, and have it whisper to you. It was common: Whereas modern life meant bears were being pushed out of populated areas, groundhogs were becoming more numerous than ever before. And it was, relatively speaking, docile — or at least it was unlikely to rip off your arm and kill you. In retrospect, the bear never had a chance.

Each February 2 of the early twentieth century saw increasing references to the groundhog in Canadian print media as references to bears declined. By the 1910s the groundhog was already clearly the front-runner, and by the 1930s the bear had all but disappeared. When Wiarton, Ontario, asserted itself as the holiday’s national headquarters in 1956 and subsequently invented Wiarton Willie, it was both the culmination of one Canadian story and the beginning of another.

“Here in Manitoba,” a newspaper noted, “no woodchuck in his senses would voluntarily emerge into the cold on February 2.”

But before we get too mournful that Canada did not retain a homegrown version of the February 2 tradition, let’s remember how unsuited that tradition is to Canadian experience anyway. As the Winnipeg Evening Tribune wrote in 1939, “This is Ground-Hog Day. So what?” The paper recounted the custom’s roots in Europe, where it was actually possible to imagine that the winter’s worst might pass so early.

“But here in Manitoba,” it noted, “no woodchuck in his senses would voluntarily emerge into the cold on February 2. [T]he Manitoba winter is unlikely to end on February 2, whether the sky is cloudy or not.”

And, of course, the folklore presumes the presence of the hibernating animal in the first place. Not all parts of Canada are so fortunate. The editor of the Charlottetown Guardian noted ruefully in 1929, “This is Candlemas Day. As we have no ground hogs on this Island we must depend on the bear for our weather predictions, and we have no bear.”

Signs of Spring

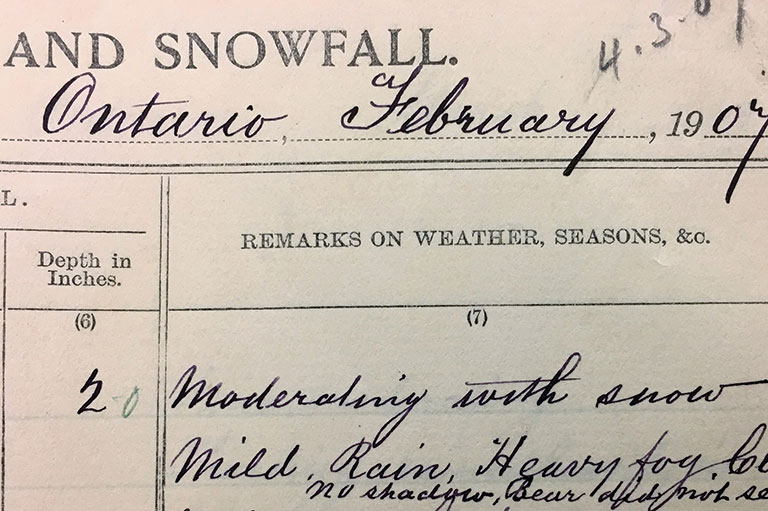

In 2014, what was then Environment Canada transferred to Western University on long-term loan its collection of historical daily weather observations recorded by volunteer observers between 1870 and 1960. Since then, students and I have pored over almost half the collection — maybe a million observations from all across Canada.

When we happened upon a February 2 observation, we looked for a reference to an animal and its shadow. But we have seen only one. “No shadow, Bear did not see it,” wrote Thomas Andrew of Arden, Ontario, on February 2, 1907.

This dearth of news related to groundhogs, or even bears, came as a surprise. But it is also a reminder that people of the past had countless other ways of interpreting the weather, the seasons, and the natural world based on first-hand experience.

In the course of Andrew’s observations, for example, he also remarked on the first spring appearance of a wide variety of birds and other animals, and he noted when plants blossomed, trees leafed, frogs piped, and lake ice formed and broke up. February 2 was just one of 365 days each year for tracking nature’s changes.

The one great advantage the Groundhog Day tradition possesses is that it is associated with a single day, a focal point that has helped it to become culturally entrenched in a way other folk wisdom about nature has not.

The irony is that, while those who make weather observations for Environment and Climate Change Canada today are far likelier to mention the groundhog on February 2, they are also far less likely to offer other natural-history information the rest of the year. In a sense, Groundhog Day commemorates, and stands in for, all the nature lore that most of us have forgotten.

— Alan MacEachern

Canada's Furry Forecasters

Wiarton Willie, the albino groundhog from central Ontario, likely has the most famous shadow in the country, but as many as ten of his extended family (including at least one puppet) attempt to predict the end of winter each year all over Canada.

Nova Scotia boasts both Shubenacadie Sam and Two Rivers Tunnel, the latter from Cape Breton Island, while Val d’Espoir, Quebec, is home to Fred la marmotte.

Over the years, Brandon Bob and Winnipeg Willow (and now Winnipeg Wyn) have provided predictions for Manitoba, while Balzac Billy — a human in a groundhog costume — does likewise in Alberta. Naturally, Toronto had to get in on the act with Dundas Donna (actually a South American coati), while just to the northeast Kleinburg, Ontario, hosts Gary the Groundhog.

— Nancy Payne

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.