Death’s Door

In the late fall, Cobourg Union Cemetery’s brooding and romantic Victorian death monuments clustered upon soft berms match the sombre, grey mood of the season. When a quiet rain falls and the light grows dim, centuries-old spruce and cedar boughs seem to weep upon the monumental tombstones with their heavy boughs. In midsummer, though, visitors may enjoy an easy breeze blowing between the grave markers and greenery. This calm, peaceful atmosphere presents a better understanding of why Victorian-era Canadians considered this space a park for refreshment and reflection, rather than a necropolis.

When Canada became independent from British rule in 1867, we were a growing nation of immigrants. Nearly one-third of the total population were of French origin, a smaller portion English, Welsh, Irish and Scottish. The remaining 2,600,000 people were born here, some with families that had been settled for generations, but the influence of Europe remained strong, including the style and structure of cemeteries.

That same year, in the small but flourishing town of Cobourg, Ont., located between Toronto and Kingston, a new era of burial traditions began. Cobourg Union Cemetery was of groundbreaking design, modelled after the garden cemeteries of Europe, which were built outside of the urban core and landscaped to offer what Cayley Bower, a researcher from Western University in London, Ont., says was “as much a desirable space for the living as a resting place for the dead.” With its sweeping berms, planted spruce trees and a trickling brook, Cobourg Union Cemetery reflected what Bower says was Victorian-era Canadian nationalism — an idealization of what it meant to conquer the wild.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

A cemetery is born

As did most garden cemeteries of the time, Cobourg Union Cemetery opened in response to the need to inter individuals outside of the growing urban core. Before the advent of large garden-style cemeteries, people were buried under church floors or in crowded church yards. As urban space became a premium and concern about unhygienic burial practices grew, the town’s leaders created a board for a newly envisioned cemetery. According to Bower, this sentiment was felt across the country, in particular in Kingston, Ont., where one of the country’s first garden cemeteries was opened.

“As the urban burial grounds grew more crowded and residential housing expanded around the graveyard, residents wanted an alternative to urban burial that came in the form of the garden-style cemetery, which represented a new and modern approach to interment,” Bower wrote in her 2017 thesis, Dying to Be Modern: Cataraqui Cemetery, Romanticism, Consumerism, and the Extension of Modernity in Kingston, Ontario.

The board of Cobourg Union Cemetery created a non-denominational, non-profit cemetery so that all residents would be assured a final resting place. Family members were originally responsible for the care of the gravesites, and it was a weekend tradition to hike the four kilometres north to the cemetery, enjoy a picnic by Pratt’s Pond on the west side and do any grass cutting around their respective family tombstones.

This new idea of the cemetery as a pleasant experience lay in great contrast to the crowded urban cemeteries that, Bower recounts, became “a space for [the] disposal of household refuse, a grazing space for livestock, and a secluded spot to engage in drinking and prostitution after dark.” Additionally, urban cemeteries were vulnerable to vandalism in the form of knocking over headstones and stealing the iron fences for scrap metal.

The 40-minute walk to Cobourg Union Cemetery deterred such spontaneous misbehaviour and was an ideal solution to provide an enjoyable and appealing place for the living to visit the dead. As the cemetery grew with additional burial sites sprinkled across its expanse, professional maintenance was required and families were asked to pay an annual fee to cover the cost.

In professional hands

As science and medicine advanced toward the end of the Victorian era, the case for hygiene introduced embalming methods in the funerary practice, replacing the personal and community involvement in handling the dead. This shift ushered in what Gillian Poulter, a historian with the Canadian Historical Association, refers to as the “traditional funeral, [which] includes the transportation of the body to a funeral home, where it is embalmed, washed, dressed, placed in a casket, enhanced with cosmetics and made available for viewing by family and friends.”

The transition was not immediately accepted in a society where there was a fear of being buried alive, says Poulter. Some people still wanted to handle the body of their loved one themselves, having it rest at home to see signs of decay before the burial. This also provided an opportunity for the community to gather for remembrance, which was spread over a number of days. However, events such as the sinking of the Titanic, which required preserving bodies for identification, and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, when people feared contracting the disease from the dead, made embalming more popular; thus, a new and lucrative industry was born. Soon, funeral directors were accused of overcharging customers for embalming and a long list of goods and services they insisted were required for a civilized burial.

The traditional funeral also became an elaborate display to commemorate the early Canadians who romanticized the heroic struggles of their nation. These deceased descendants of heroes were memorialized by elaborate funerary and professional burial treatments, topped off with a magnific burial marker for all to see. These markers, often rich in cultural significance and meaning, reflected the upright religious and moral social norms of the time.

Advertisement

Status in death

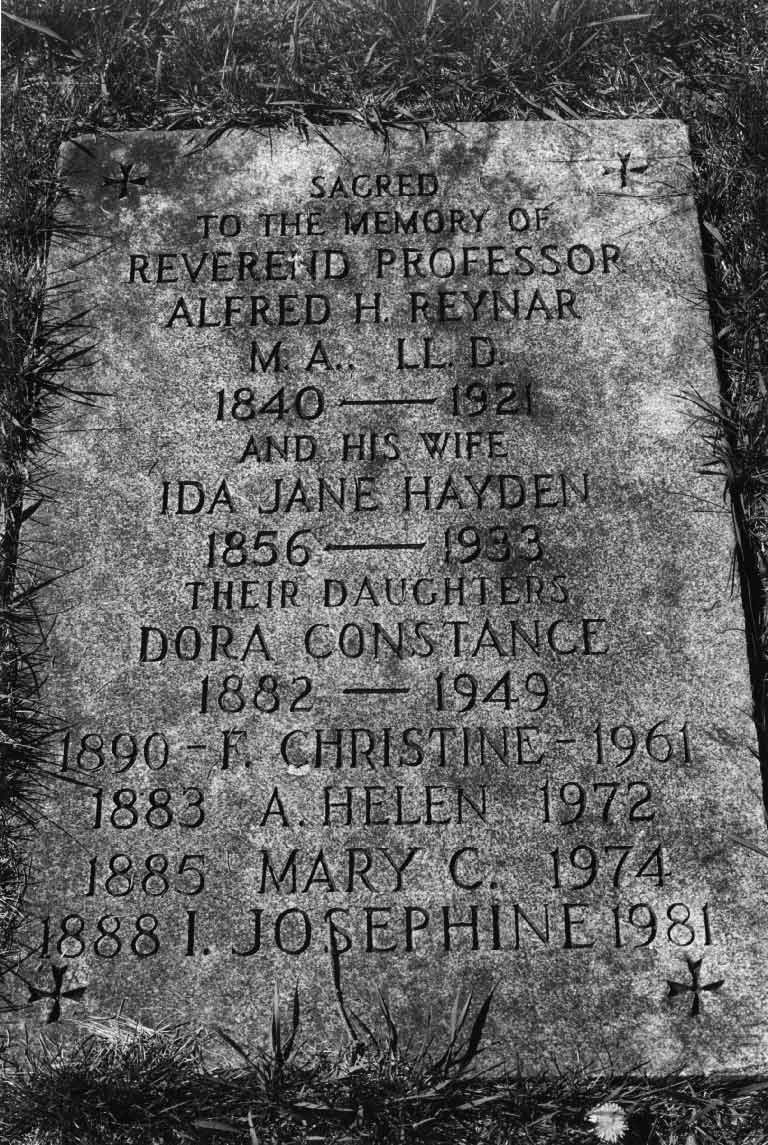

At Cobourg Union Cemetery, many large gravestones are prominently engraved with the name of a male figure, followed by the name of his spouse and finally the children, if any, in smaller letters around the sides of the monument. Sometimes, small nameplates were set in the ground, creating a perimeter of family exclusivity.

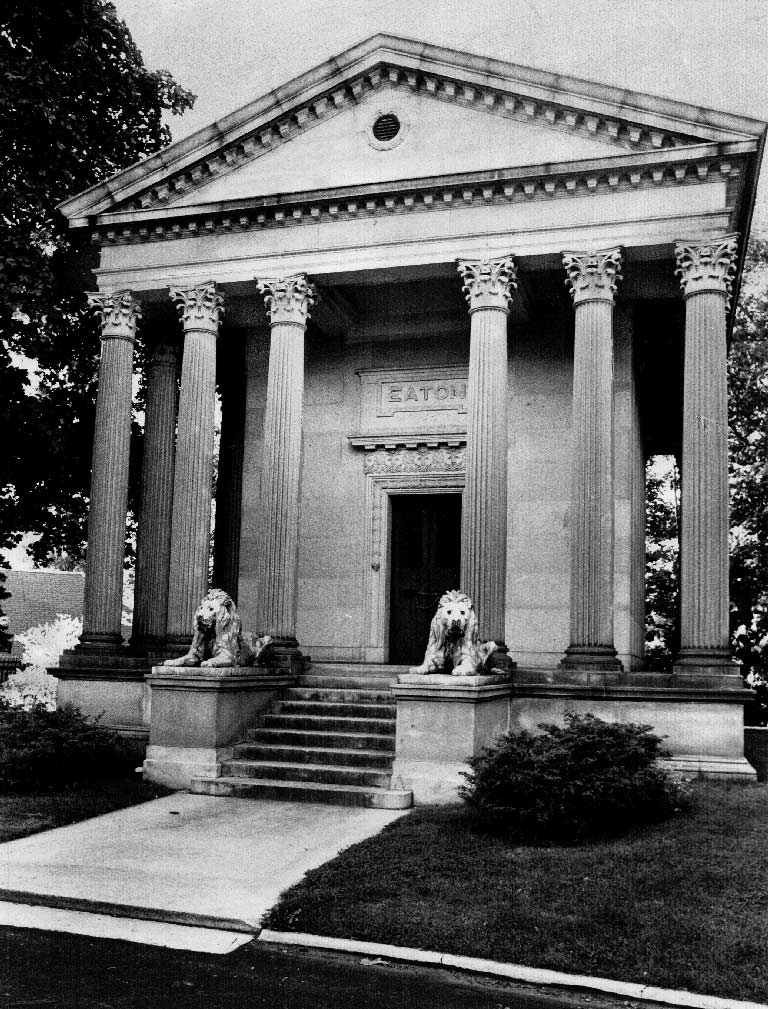

One of the Cobourg cemetery monuments looks like the Stanley Cup, with its bowl on a cylindrical stand; both are made of black granite, patinaed with time. The Stanley Cup is, of course, a symbol of being the best team in the National Hockey League. In the minds of early Canadian settlers striving to make their mark, this monument would certainly have been a grand gesture. According to Bower, by the end of the 19th century, burial had become “theatre for a final staging of social position.” Elaborate funeral monuments were expensive and reflected the success of those Canadians who were able to conquer the wild and succeed in a new nation.

Returning to community

The decades that followed the 1901 death of Queen Victoria would see two world wars bookending a great economic depression and sweeping social transformations. People distanced themselves from the Victorian era and were interested in new innovations and technologies, along with a cleaner aesthetic — think art deco and mid-century architecture and furniture. This change was reflected in the introduction of the lawn cemetery, where wide-open spaces carpeted in trim green grass replaced the ornamental trees, shrubs and monuments of the Victorian cemeteries.

Extravagant mourning practices gave way to simpler, more restrained forms of commemoration. In British Columbia, the rise of a new suburban middle class after the Second World War brought with it a desire to avoid the constant reminders of mortality found in traditional cemeteries. Instead, there was a growing preference for cleaner, more orderly burial grounds that blended into the suburban landscape.

Modern cemeteries, like Burnaby, B.C.’s Ocean View Burial Park, established in 1924, introduced strict guidelines on the size and shape of monuments. Tall, imposing headstones were no longer welcome, considered both impractical and visually outdated. In their place were flat or midsize markers, chosen for ease of maintenance and a more unified aesthetic. Ornamental family plots and iron enclosures were phased out and uniformity became a defining feature. This new approach reflected broader social ideals: Cemeteries were now more inclusive public spaces, where modest markers served as equalizers between classes. Even in military sections, this design ethos emphasized national unity over individual distinction. As headstones grew smaller, epitaphs became shorter — often listing only a name and the dates of birth and death. In many cases, words like “death” and “dead” were omitted entirely, signalling a cultural movement toward distancing oneself from the finality of mortality.

Significance of cemeteries today

These days, cemeteries are recognized for their historical and cultural value, particularly when it comes to community record keeping. Monument inscriptions provide vital information on family lineages, cultural customs and demographic trends, such as average age at death during specific time periods.

But their tranquil beauty is also appreciated. Toronto’s impressive Mount Pleasant Cemetery attracts hikers, snow-shoers and bird watchers alongside guided walking tours — evolving uses that reflect a growing recognition of cemeteries as peaceful multiuse spaces that blend memory, nature and community engagement.

A well-maintained urban cemetery can provide a peaceful, reflective atmosphere that promotes stress relief and contributes to overall mental well-being. Mature trees provide shade while offering habitats for birds and other wildlife displaced by ongoing urban development. In this way, Canadian cemeteries contribute to both the environmental sustainability and the livability of modern cities, serving as quiet sanctuaries of green space within densely built landscapes.

It seems that, once again, cemeteries are places for the living as well as the dead — open-air museums that tell the stories of the culture, history and social meaning of a place.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement