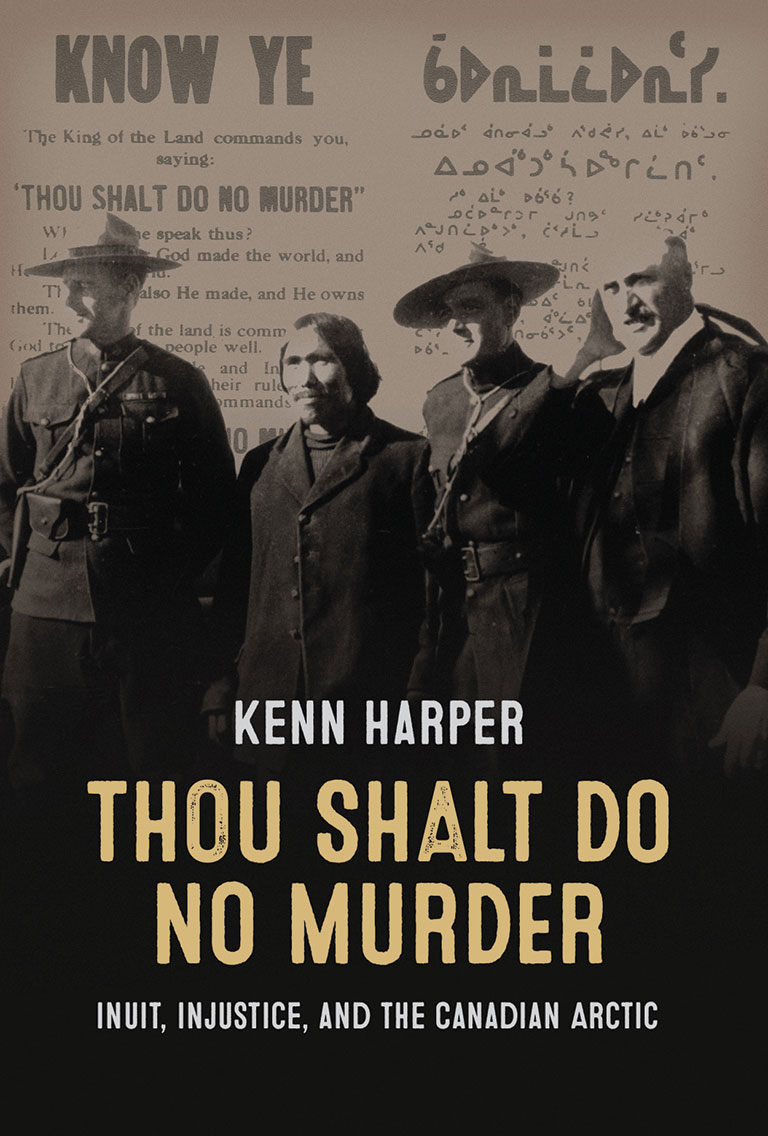

Thou Shalt Do No Murder

Thou Shalt Do No Murder: Inuit, Injustice, and the Canadian Arctic

by Kenn Harper

Nunavut Arctic College Media, 452 pages, $38.95

In 1923, three Inuit men were put on trial at Pond Inlet, on Baffin island, for the killing of qallunaat (white) trader Robert Janes. This story is not widely known outside the North, but it has fascinated me ever since I discovered Shelagh D. Grant’s book Arctic Justice over a decade ago.

Kenn Harper has been gripped by this history for much longer and has produced a hefty tome entitled Thou Shalt Do No Murder: Inuit, Injustice, and the Canadian Arctic.

Harper has lived in the Arctic for fifty years, working as a teacher, historian, linguist, and businessman. He speaks Inuktitut and is the author of the bestselling Give Me My Father’s Body (recently republished as Minik: The New York Eskimo and optioned for film).

He first heard of the Pond Inlet trial in the 1970s, shortly after he moved north. It is clear both from the text and from his bibliography that Harper has immersed himself in this history via many hours spent with Inuit elders and much time in archives.

One of those elders, Jimmy Etuk, was alive when the killing and the trial took place. It is Etuk who begins the book in gripping style. His “speech was volcanic,” Harper tells us, as Etuk launches into the tale of Robert Janes’ descent into apparent madness and the circumstances that apparently forced Nuqallaq and two other Inuit men to end his life.

After this dynamic beginning, Harper switches to a more traditional social and economic history of early whaling, European-Canadian exploration, and the imposition of Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic. For one hundred pages, Etuk and other Inuit fade into the background, as the focus becomes almost entirely the qallunaat male representatives of these histories: Joseph-Elzéar Bernier, William Duval, Captain Henry Toke Munn, and, of course, Robert Janes.

Robert Janes’ apparent descent into madness led Nuqallaq and two other Inuit men to end his life.

This section sets up the dynamic of “gentleman rivals” and their distrust of one another, and it introduces the threats, sexual jealousy, greed, cultural clashes, climatic conditions, and mental illness that are the ingredients in this stewing pot.

The promise of the book — the trial — and the author’s unique Inuit access and cultural and linguistic insights, however, almost disappear from view. There are even times when the qallunaat records seem to be taken at face value, despite the fact that with Harper’s background he had an opportunity to read against the grain and to contextualize them more.

There are certainly bright spots in this section. Harper’s examination of language — Inuktitut, English, and French — and its importance in these encounters is fascinating. He is also able to provide useful background about Inuit practices regarding sex and kinship ties at the time.

Harper does an excellent job painting a balanced picture of Nuqallaq and Janes from both qallunaat records and Inuit oral histories. It is easy in a narrative rife with hypocrisy and sham trials for a person like Nuqallaq to be shown simplistically as a victim, but Harper resists this urge.

Neither Janes nor Nuqallaq invite much sympathy: Both were obstreperous and physically abused their wives. (This was one major sticking point for me in the book. Harper writes, “One wonders how Inuutiq, the acquiescent husband, felt” about his wife being beaten by Janes. My immediate thought was: How did she feel about it?)

Through the depth and breadth of his sources, Harper shows that both men were victims not only of their own shortcomings but also of the larger forces of history. Thou Shalt Do No Murder leaves the impression that Canadian sovereignty and the “economic enslavement” of the Inuit — as Munn wrote regarding the approach of Hudson’s Bay Company trader Ralph Parsons — were more important than actual justice in Pond Inlet.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Our online store carries a variety of popular gifts for the history lover or Canadiana enthusiast in your life, including silk ties, dress socks, warm mitts and more!