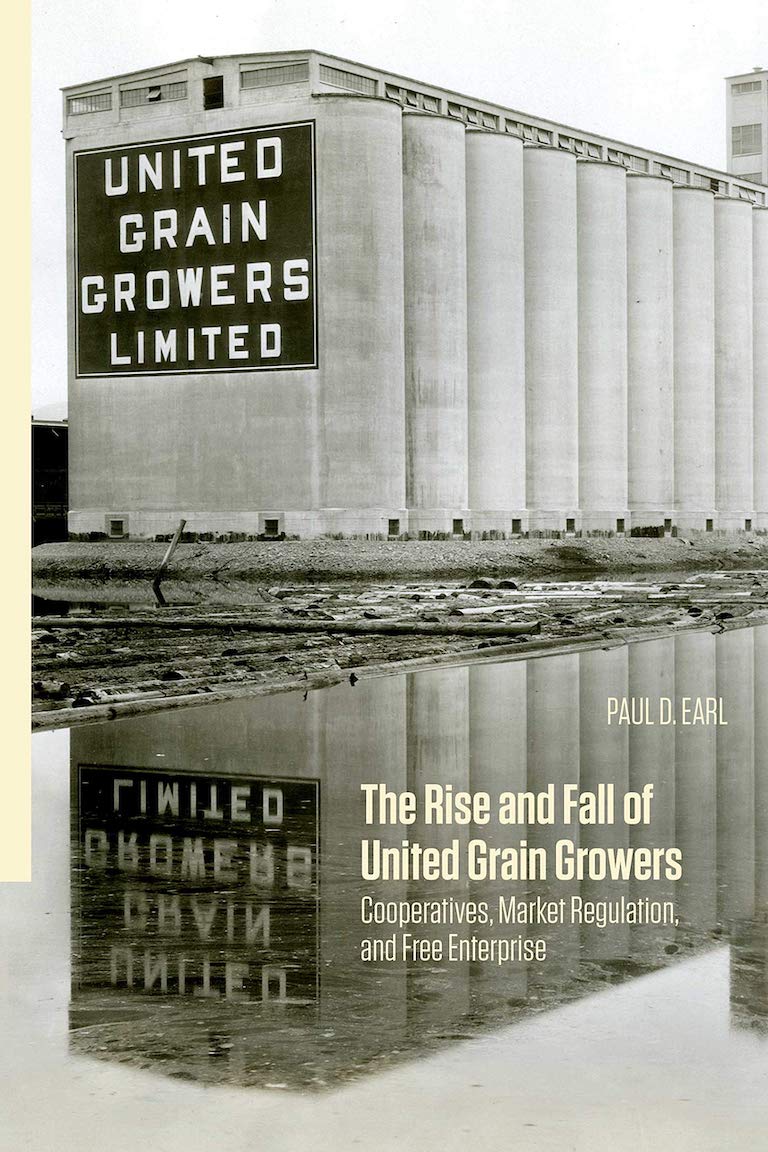

The Rise and Fall of United Grain Growers

The Rise and Fall of United Grain Growers: Cooperatives, Market Regulation, and Free Enterprise

by Paul D. Earl

University of Manitoba Press,

363 pages, $27.95

In The Rise and Fall of United Grain Growers, Paul D. Earl traces the history of the Winnipeg-based co-operative grain marketing company from its origins in 1906 to its fall in a corporate takeover a hundred years later. The book’s structure is comprised of three parts representing the company’s birth and growth, its maturity and decline, and its later demise.

Earl’s book began as a commissioned company history, but the diappearance of United Grain Growers (UGG) shifted his focus to such issues as how shareholder rights and corporate governance played in to its end. The last section, discussing the circumstances of the company’s fall to a corporate takeover in 2007 by the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool (since renamed Viterra), comprises nearly half of the text.

The United Grain Growers became a major force in grain marketing in the first half of the twentieth century. Beginning as the Grain Growers’ Grain Company (GGGC), established by Edward A. Partridge and other farmers at Sintaluta, Saskatchewan, it was the first farmer-owned grain-marketing business in Western Canada.

Partridge was a strong proponent of government control over grain marketing, although provincial governments balked at his proposals for socially controlled grain elevators. As a result, the wheat pools and the GGGC (which became UGG after its 1917 merger with the Alberta Farmers’ Co-operative Elevator Company) were always obliged to compete with private grain companies on the open market and remained subject to numerous internal and external economic forces that bore upon their viability.

Following initial conflicts over its direction, UGG prospered under Thomas Crerar, the first of a series of talented leaders who shepherded the company through its rapid expansion. By the First World War it was sustained by a healthy membership of about sixteen thousand producer-shareholders who were organized in a network of local associations supporting the company’s goals and activities.

Throughout its history, United Grain Growers navigated the vagaries of grain marketing amidst constantly changing situations. These included the need to represent the interests of farmers but also the necessity of remaining profitable while maintaining its aging infrastructure. Where modernizers such as Mac Runciman, UGG president from 1961 to 1981, sought to rationalize its elevator system, the company’s members pushed back. They pressed for the retention of country elevators, a source of tax revenues that were critical to their communities’ survival. The consolidation of elevators eventually took place, but the drawn-out process was a drag on UGG’s returns.

Meanwhile, the company was hampered by the failure of the federal government to develop a comprehensive policy to modernize the transportation system, something further complicated by resistance to changes to the long-standing Crow rate — a mandated price that made grain haulage by the railways uneconomical. Pressure was also exerted by non-farming shareholders seeking higher returns; they ultimately prevailed over a dwindling percentage of farmer-shareholders.

Earl’s detailing of these and other challenges to UGG over successive eras is well developed. In the latter part of the book he seeks to explain the 2007 takeover through the lenses of legal and business rationales, and he elaborates arguments both for and against the sale of Agricore United (the company’s name following a 2001 merger). In a thoughtful discussion, the author considers the role of ideologies in driving the perspectives of opposing parties; but he declines to take a definitive position, leaving readers to draw their own conclusions.

The book largely omits consideration of the implications of the federal government’s failure in recent decades to maintain a regulatory regime for the grain trade that was strong enough to protect the interests of both prairie farmers and the country in the context of globalization. These implications include the yielding of Canadian sovereignty through a succession of mergers and sales to foreign interests, unintended consequences of deregulation, and the continued vulnerability of prairie farmers under the international price system.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement