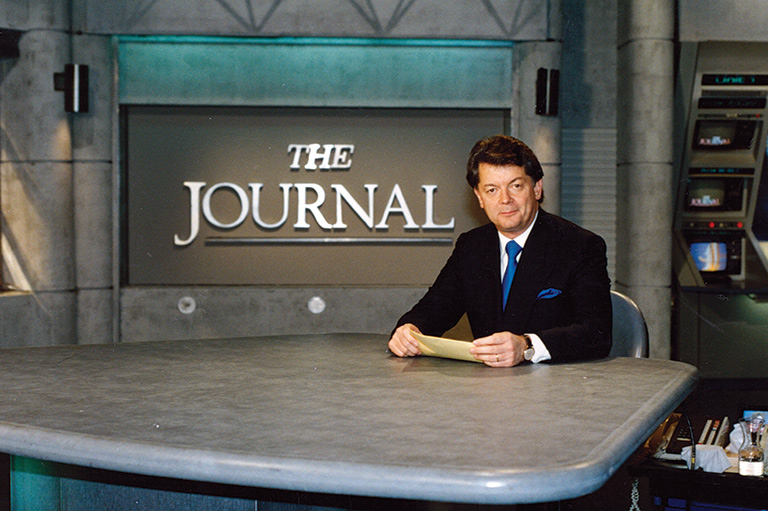

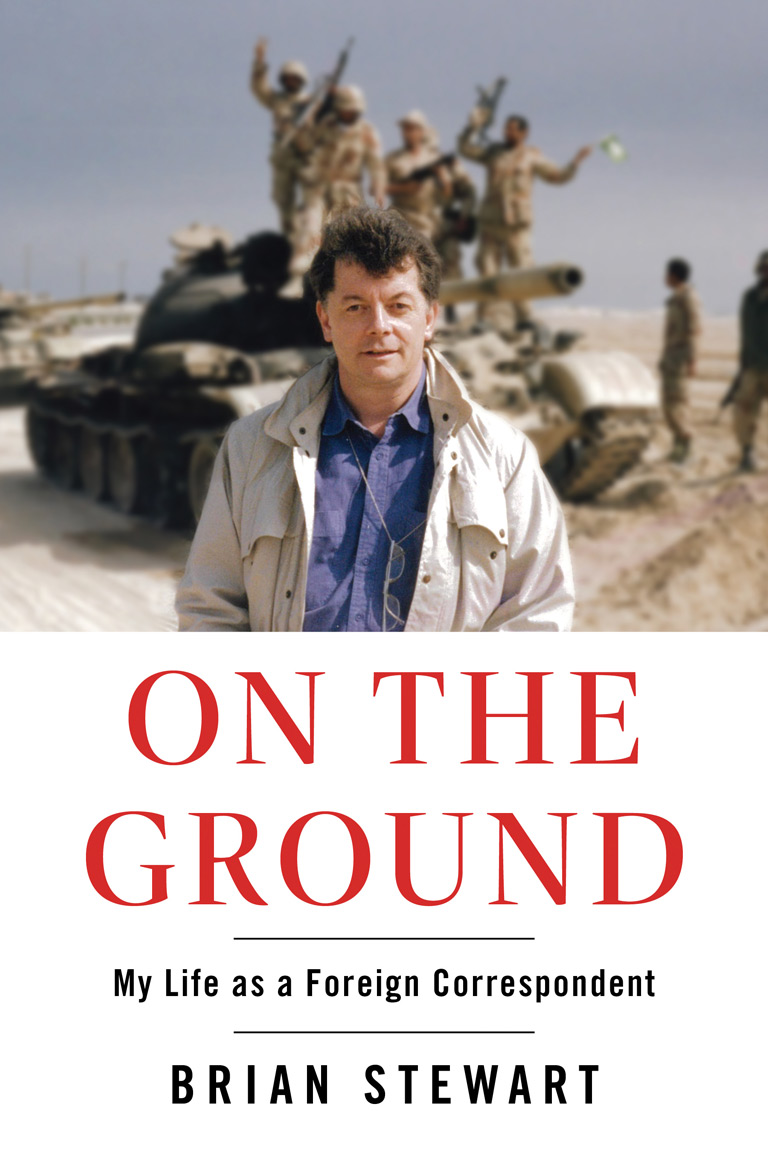

Reporting Back

Is there a moment in your career that stands out for you?

The one that affected me the most was the Ethiopian famine [in the ’80s] because that deposited me and a small CBC crew in the epicentre of the worst famine since the Second World War — one that threatened seven million people. Seeing mass suffering on that scale really scarred me and taught me two things: first, that journalism had to let the world know what was going on; and second, journalism often made the mistake of rushing in, covering catastrophes and then going away. So, I go back to many of the stories I covered before and try to update people.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

So for you, after covering world crises like the Ethiopian famine, why did you feel it was important to return to those stories and follow up to show how things had or had not improved?

I covered Beirut, the civil war in Lebanon in the ’80s, right around the same time I was doing Ethiopia, and it always occurred to me, “Boy, the city keeps getting knocked down to the canvas, but somehow it keeps getting up again.” You take days of shelling and fighting, then two hours later, they were putting the glass back in windows, people were shopping, and kids were going to school. I said, we have to be able to portray that side of the story to audiences as well, because otherwise, audiences understandably do get donation fatigue.

That was a danger of a lot of the crisis reporting, when piled with 24/7 news, satellites, information pouring in on us to such an extent, there was a real danger there that the mass audiences watching this would just become desensitized and wonder if all the effort and the money did any good whatsoever.

In your reporting, did you see events where you thought, “This is history repeating itself”?

Yes, for sure. It’s so important for journalists to know their history and have a sense of the history in the areas that are covering. A good example would be Afghanistan. The year before Canada decided on its first mission to Afghanistan, to Kabul after 9/11, the Canadian Army had done an exercise to decide what was the worst country in the world that a Canadian force could actually be deployed to. They studied all the possible horrible scenarios, and it was Afghanistan. I think the reporting at the beginning of Afghanistan should have been a lot more sober and somber than it actually was, and that was because people did not really understand the history of what they were getting into.

If you were reporting today, how do you feel that the internet, social media and widespread disinformation would impact the way you report?

Well, I’d have much more information quickly. We would work on a story for a week; now, they want the story that afternoon, or the next day. I do recognize that journalists today have certain advantages — not only the training they receive but also the remarkable access to information, and hopefully, a lot of good, solid common sense. How do we accept a tsunami of information and filter it properly so we’re getting the goods and not just informational mayhem?

How important is journalism, particularly from foreign correspondents, today?

It’s tremendously important. We face a real information crisis in much of the western world, where foreign bureaus are being closed down and foreign correspondents are being reduced, so we’re relying more on outside sources of information. Canada really needs far more foreign correspondents out there reporting on issues that affect Canada and Canadians.

In your book, you talk about coping with the horrors that you witnessed and not realizing the impact on your mental health until later in life. And you helped bring attention to the impact witnessing trauma has on foreign correspondents. How do you regard the role you’ve played in helping to bring that issue to the forefront?

There was a time before the ’80s and well into the ’90s, when foreign correspondents were just assumed to be OK, sort of a Hollywood image. They drink heavily at the bar —self-medicate if they had emotional problems — but when they got home, it was assumed they’d look after themselves.

I got really sick from the effects of what had disturbed me — separate from PTSD, something called “moral injury.” The study was taken up by a psychiatrist in Toronto, Dr. Anthony Feinstein. He was the first one to examine what is happening to the foreign correspondent population that suffers from what it sees, the threats and dangers it comes under. One result is moral injury — that injury to the soul you get from witnessing horrible things and feeling you didn’t do enough personally to help. That can haunt your later years as much as and maybe even more tenaciously than PTSD. But Feinstein was the one who led the charge on getting the media heads up here to start taking care of mental welfare of their employees.

Not everyone working overseas gets these problems, but enough of it happens. Conflicts tend to go on longer, and they get worse in terms of human suffering, it seems. Imagine covering Gaza. And the people who witness that — not just journalists, but aid workers, military observers, diplomats — they too are prone to this very grave punishment that can befall the witness to the worst aspects of humanity.

Advertisement

These days, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed, what with climate change, the Trump administration, Gaza, Ukraine and more. You’ve witnessed all kinds of terrible situations — what gives you hope?

You do see the worst moments often turn not so bad. I wrote a diary throughout the October Crisis [in 1970], when we thought the world might be blown apart. A couple of years later, we’re talking about better relations with the Soviet Union, and the Cold War mellowed its way out to eventual oblivion in the ’80s.

In terms of the American situation, it’s very hard to be optimistic. I’ve seen awful moments in America: the McCarthy era, the 1960s with the riots, the segregation battles and cities burning — all of that upheaval and misery. So, I’m old enough to say, well, there’ll be a change, and people will get tired of the thuggery, the appalling manners and the lies. A year into it, there may be a real fatigue with this monstrous circus show that the United States president is foisting on the whole world, and people might say, “It’s time for the end of Trumpism.” I would like to say I’m confident that’s going to come, but I’m not because I’ve never seen anything quite like the Donald Trump phenomenon. And I hope to hell I never see anything like it again.

In today’s environment of misinformation and disinformation, it can be hard to know who to believe. At Canada’s History, we tell the true stories of Canada’s diverse past, sharing voices that may have been excluded previously. We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past, highlighting our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages – award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts. Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!