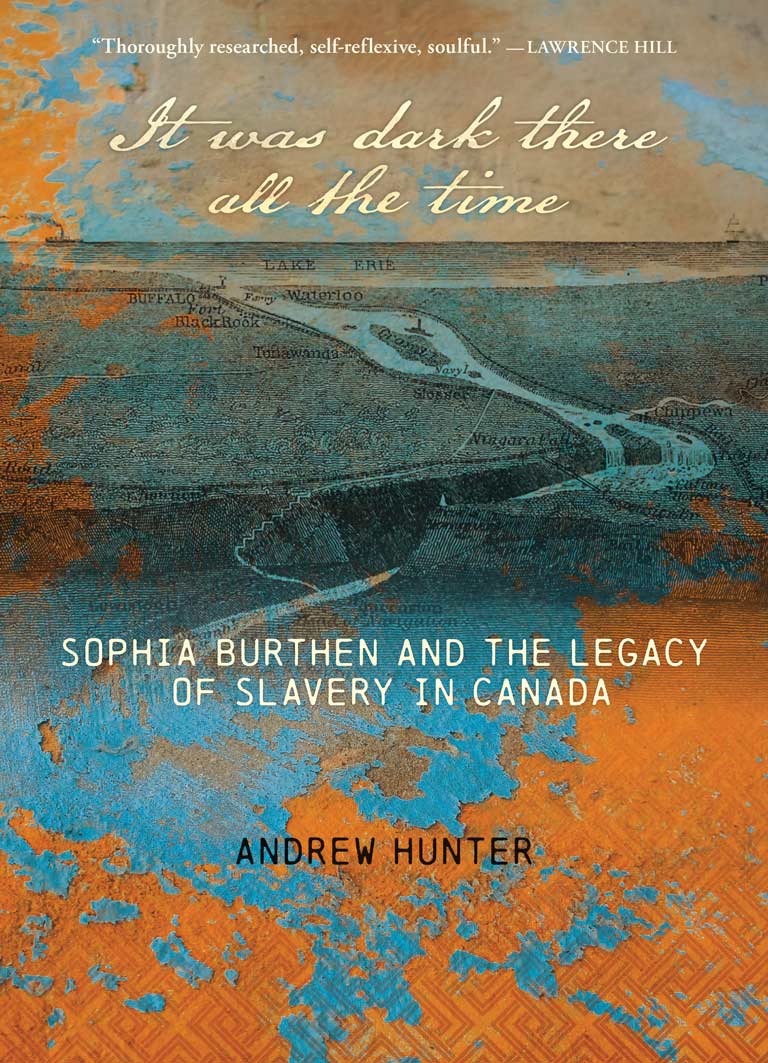

It Was Dark There All the Time

It Was Dark There All the Time: Sophia Burthen and the Legacy of Slavery in Canada

by Andrew Hunter

Goose Lane Editions

328 pages, $24.95

Hamilton writer, historian, and arts curator Andrew Hunter has written a historical account of the life and times of Sophia Burthen Pooley, a Black enslaved Upper Canadian woman. His book It Was Dark There All the Time pays a stirring tribute to Pooley by expanding upon the three-page biographical sketch written about her in 1856 by Boston educator Benjamin Drew (and which is included as an appendix in Hunter’s book).

In 1855, Drew visited Canada West — the region was earlier called Upper Canada and later became Ontario — to report on the condition of life for Black freedom seekers, many of whom had sought refuge in Canada via the Underground Railroad. Drew interviewed a number of these Black people who were now building a life in freedom, including people in twenty different towns, cities, and villages. Then in her nineties, Sophia Pooley was among the Black people living in the area known as the Queen’s Bush, between Waterloo County and Lake Huron. Drew interviewed her and wrote down her autobiographical narrative.

From this story we learn that Sophia Burthen was born a slave in Fishkill, New York, in the Hudson Valley. She lived in the home of her enslaver with her sister and her parents. At the age of seven, she was kidnapped along with her sister by her owner’s sons-in-law. The passage in which Pooley provides this information is also the passage from which Hunter takes the title of his book: “My parents were slaves in New York State. My master’s sons-in-law … came into the garden where my sister and I were playing among the currant bushes, tied their handkerchiefs over our mouths, carried us to a vessel, put us in the hold, and sailed up the river. I knew not how far nor how long — it was dark there all the time.”

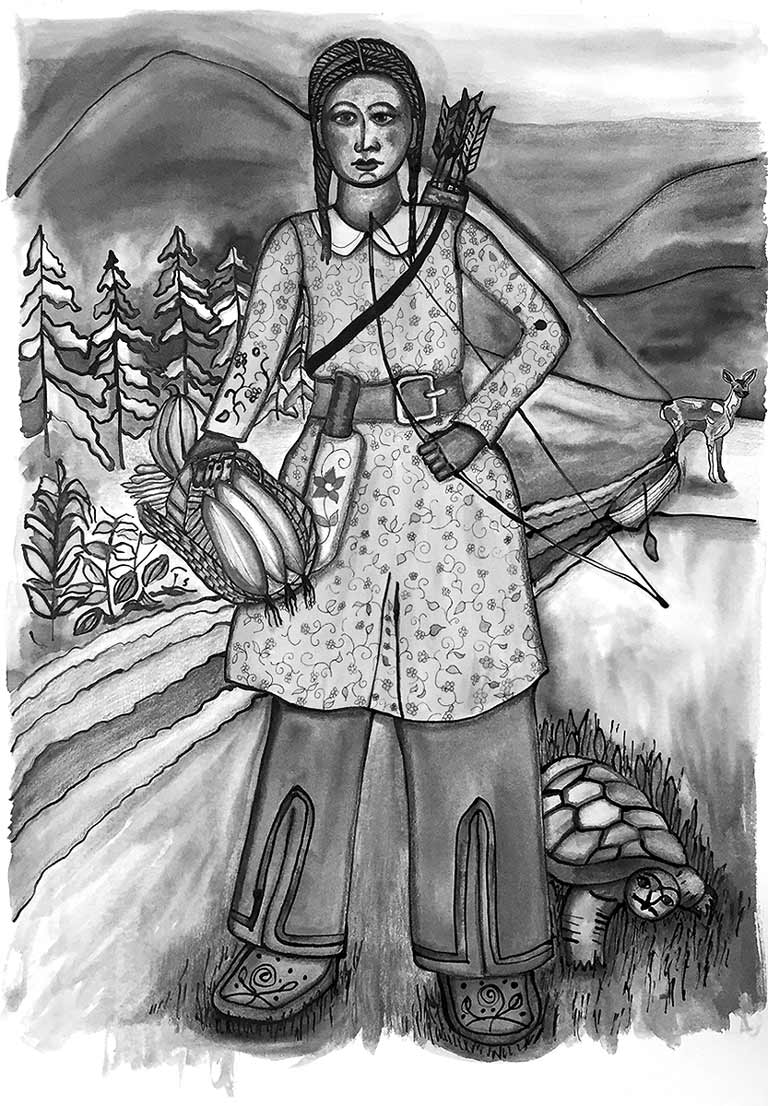

The betrayal, fear, and fright she experienced at the hands of these men are evident in this passage, as is the traumatic separation from her parents. The robber sons-in-law eventually sold her to Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant, or Thayendenagea, who was living in New York State at the time. Brant sided with the British during the American Revolutionary War, and, after the war ended with a British loss, he and thousands of his people from the Haudenosaunee Confederacy migrated to Canada. In tow were the enslaved Africans, including Burthen, whom Brant owned. The Mohawk chief was given the Haldimand Tract upon which to settle, and he built several homes in at least three townships.

Because Burthen entered the Brant household an early age, she was assimilated into Mohawk culture: She spoke the Mohawk language, dressed in Mohawk fashion, and hunted deer with Brant’s children using a tomahawk. She also suffered abuse at the hands of Brant’s wife. Perhaps Burthen suffered an identity crisis, one born of loneliness in the Brant household and in the community at large, as well as due to the separation from her birth family. This could have been what prompted her to say to Drew, “I guess I was the first colored girl brought into Canada.” At least for a while, she saw no one else who looked like her.

Several years later, Brant sold Burthen to a white man named Samuel Hatt. She lived with him for the next ten years, until she self-emancipated and escaped into a life of freedom around 1793. In freedom she married a Black man, Robert Pooley, who abandoned her soon afterwards.

It was decades later when Drew encountered Sophia in the Queen’s Bush, and she was elderly. We do not know if she had given birth to any children, but she was living there without any biological kin, after she had been given refuge by the Black denizens of the Queen’s Bush. Pooley had endured the ravages of war, migration, and slavery, and she had lived to tell her story.

In the printed version of Drew’s book — entitled A North-Side View of Slavery. The Refugee: or the Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada. Related by Themselves, with an Account of the History and Condition of the Colored Population of Upper Canada — the interview came to three pages. Hunter in turn took these pages as the basis for a three-hundred-page book. To do this, he investigated every known location where Sophia Burthen Pooley had lived or stopped, whether in New York State or in Upper Canada. Those places include Fishkill, Albany, and Niagara in New York, as well as Burlington, Brantford, Dundas Inlet, Ancaster, Stoney Creek, and the Queen’s Bush in Canada.

Hunter invests the geography with her presence and builds stories for every stop along the trail, at each step providing a natural history of the area. For instance, at Fishkill, where the story begins, he provides a lesson on the significance of blackcurrants and their natural history, since it was among the currants that Sophia and her sister were playing when they were kidnapped. The story ends at the Queen’s Bush, where Pooley most likely died and is buried. Day lilies and periwinkles are the plants that punctuate the Queen’s Bush portion of Pooley’s life.

Hunter includes information that Pooley did not provide to Drew, or that at least was not recorded. For example, he engaged in extensive research to trace the origins of Pooley’s Fishkill enslaver, the father-in-law of the men who kidnapped her. In this regard, Hunter works like a genealogical detective and takes readers to the Netherlands and to various locations in colonial Dutch New York where the enslaver had his origins and roots.

He interweaves Pooley’s history with his own background as a White Canadian of Scottish descent, contrasting Pooley’s history of enslavement with his own life narrative of freedom and comparing her lack of privilege to his privilege. But there is more: Hunter lives in the area where Pooley lived first with Brant and then with Hatt. He lives in the Stoney Creek area of Hamilton, where Pooley lived two centuries earlier, and he knows Dundas, where she caught deer with the Brant children. He traversed these places in the footsteps of Pooley, and his familiarity with what I call the “Pooley landscape” infuses the book with an intimacy that brings readers up close to Pooley herself and to the events of her life.

To ground Pooley’s story and to provide context, Hunter provides a lesson on the history of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (people of the longhouse) that united several Indigenous nations. The pact among these nations was broken during the American Revolution, when tribes made allegiances with either the British or the Americans. Brant and his Mohawks sided with the British. The split in the confederacy, as well as the aftermath of the war, severely impacted Black people on both sides of the border, whether they were enslaved or free, and Sophia Burthen Pooley was one of those Black victims of the war.

Hunter also includes an extensive discussion of Samuel Hatt and his family. Hatt was also of Scottish origin and made his fortune in the Hamilton and Stoney Creek area.

In discussing Burthen’s enslavement, Hunter hints at possible sexual abuse in both the Brant and Hatt households. Sexual abuse of Black enslaved females was a mainstay of the slavery system wherever it was practised. This was not something, though, that a ninety-plus-year-old woman would tell a white man who came to interview her. But what Pooley did tell Drew, and what Hunter discusses, is the physical abuse she experienced at the hands of Brant’s wife, including the disfigurement she suffered as a result.

Regarding her time with Hatt, we know even less. We learn only that she was a teenager while in his household and ran away into freedom when John Graves Simcoe came as the first Lieutenant-Governor to Upper Canada and passed a law to limit slavery in the colony. Hunter nonetheless makes the Hatt episode more robust by giving a history of the Hatt family and its genealogy

What many readers will find amazing is the fact that Burthen was a Canadian slave. Yes, slavery happened here — in Canada. And, as I have noted elsewhere, she did not travel from the United States on the Underground Railroad to find freedom in Canada, as was the case for most of the people Benjamin Drew interviewed. Rather, she left the United States to continue enslavement in Canada. Drew came to Canada to interview runaways from American slavery, and Pooley therefore was an anomaly — which makes her story stands out even more. (I have written extensively on Pooley in The Enslavement of Africans in Canada, a booklet published in 2022 as part of the Canadian Historical Association’s Immigration and Ethnicity in Canada Series.)

Drew’s telling of her story is sparse, and Hunter puts flesh on the bones of this story. He makes the point over and over again that enslaved people rarely are written about — so he sets out to give Pooley a robust story, and he succeeds!

Looking through a feminist lens, he takes issue with the fact that within the literature she is called “Pooley” — her husband’s name. Perhaps it’s because her husband abandoned her that Hunter does not think she should carry his name. He thinks it is better to call her “Burthen” — her maiden name and the birth name bequeathed to her by her parents.

Hunter’s narrative is interspersed with what I call love letters to Sophia. In these letters, he laments her enslavement, informs her about what has taken place after she died, explains why he as a modern privileged white male is writing her biography, tells her about the Black abolitionists Sojourner Truth and Josiah Henson, provides geological details of the Hudson Valley, tells Sophia about her family (and those of her family’s enslavers), and relates to her the meaning of her name Sophia (wise and beautiful). In some of these letters, he exhibits white guilt by apologizing for his race.

The title alone will make prospective readers want to snatch the book up and read it. The kidnapping scene from which Hunter’s title is derived is reminiscent of the experience of African slave captives who were chained at the bottoms of ships that crossed the Atlantic Ocean from West Africa to the New World. Sophia Burthen herself experienced a middle passage moment, tied up and sailing on a vessel not across the Atlantic Ocean but along the Hudson River.

I do find something odd about Hunter’s work: In discussing the bibliography about women and slavery in Canada, he seems unaware that I wrote a groundbreaking book on the topic, in which I discuss Pooley at length. Not once did he mention my book The Hanging of Angélique: The Untold Story of Slavery in Canada and the Burning of Old Montreal. Angelique, for once and for all, cemented the history of Canadian slavery in the consciousness of Canadians.

Further, in 2007, at Ontario’s commemoration of the bicentenary of the British Parliament’s act to abolish the slave trade, I showcased Sophia Pooley in the exhibit Enslaved Africans in Upper Canada, which I curated with the Archives of Ontario. This exhibit has been online since its inception in 2008. But Hunter seems unaware of both of these interventions in shining the spotlight on Pooley. Thus, while he laments history having ignoring Pooley, he ignores two important texts pertaining to her life.

Nonetheless, It Was Dark Here All the Time is a significant piece in the literature, begun by Benjamin Drew, on the history of Sophia Burthen Pooley. Hunter’s intervention has added another layer to the history of the enslavement of Black people in Upper Canada and their quests for, and journeys to, freedom.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!