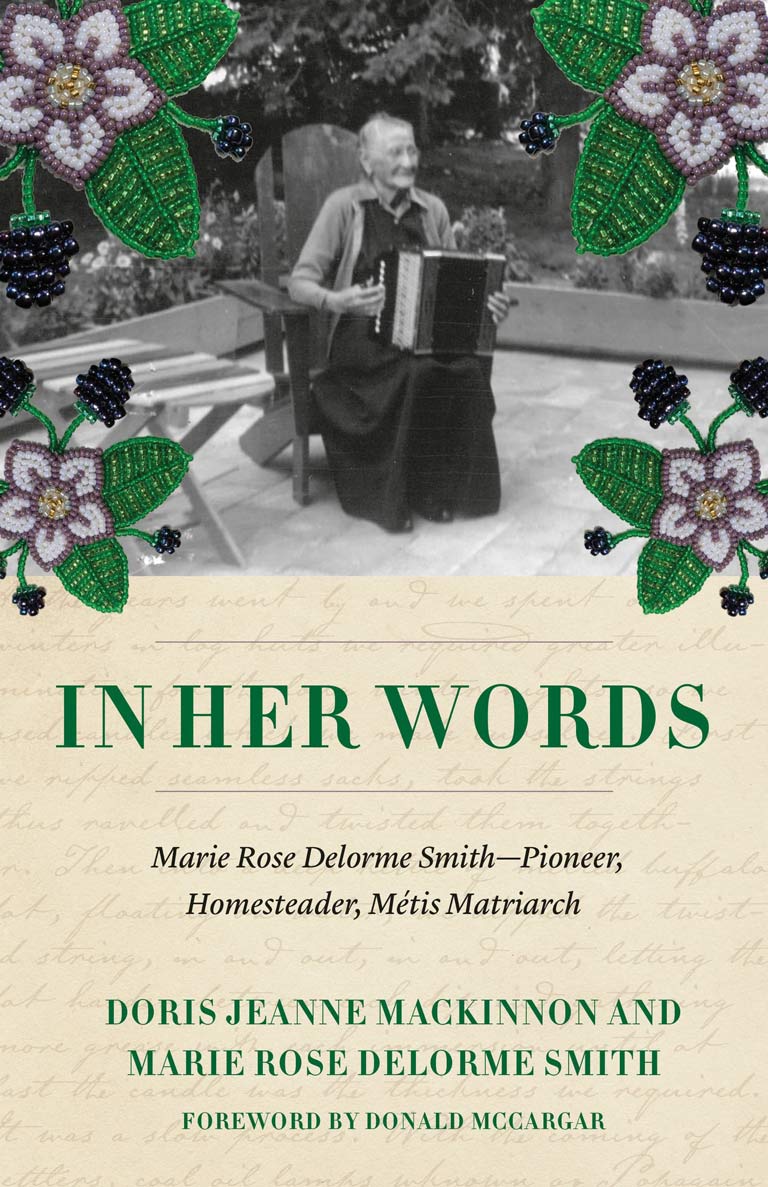

In Her Words

In Her Words: Marie Rose Delorme Smith—Pioneer, Homesteader, Métis Matriarch

by Doris Jeanne MacKinnon and Marie Rose Delorme Smith

Heritage House Publishing

288 pages, $29.95

In 1877, a 16-year-old M.tis girl named Marie Rose Delorme was “given” in marriage to the white fur trader (and future rancher) Charlie Smith for $50. In her own words, much later — for Delorme Smith became a record keeper and chronicler in the last decades of her nearly 100-years-long life — she would reveal, “I might as well say I was sold.” The purchaser was a Norwegian close to 20 years her senior.

Delorme Smith was convent-educated and spoke French, English, Cree and likely Michif. Her fur-trading grandfather had been a leader in the Red River community and her uncles served with Louis Riel’s army. The family followed a traditional lifestyle, crossing and recrossing the plains, “following the treaties.” Later, Delorme Smith and her carousing husband were ranchers near Pincher Creek, Alta., where he often invited the neighbourhood in to drink.

She describes laying her children across a bed like sardines, to protect them from the drunks crashing around in their one-room log house. She tried replacing the liquor in the barrels with a mixture of water, mustard, red pepper and salts, but “they drank it all and never knew the difference.” Instructed through the church and the somewhat-alien culture of the Europeans to obey her husband, she believed he was “the boss.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

But Delorme Smith prevailed. She became a midwife and healer, coming to know local heroes such as Col. James Macleod, NWMP commissioner and, later, a justice on the first Supreme Court of the North-West Territories. Delorme Smith also joined pioneer women’s groups that aimed to preserve the fast-fading days of the first Europeans in the West.

It’s an astonishing life. The aim of this volume, part essay by Doris Jeanne MacKinnon — her third book about this matriarch of the Prairies — and part original writings retrieved by MacKinnon after being handled by family and two public archives, is to give the latter her voice back. Historians get twitchy about that voice because Delorme Smith was a woman of her time. She alternated between romanticizing her marriage and warning young women against marrying young. She flipped between making racist comments about “Indians” and expressing empathy and respect for their ways. To me, these inconsistencies are a strength; they bring her alive. Delorme Smith died in 1960; 62 years later, she was recognized as a “national historic person” by the Canadian government. Her papers, including bits of memoir, accounts of treaties and accounts of death (12 of her 17 children predeceased her), are now at the University of Calgary.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement