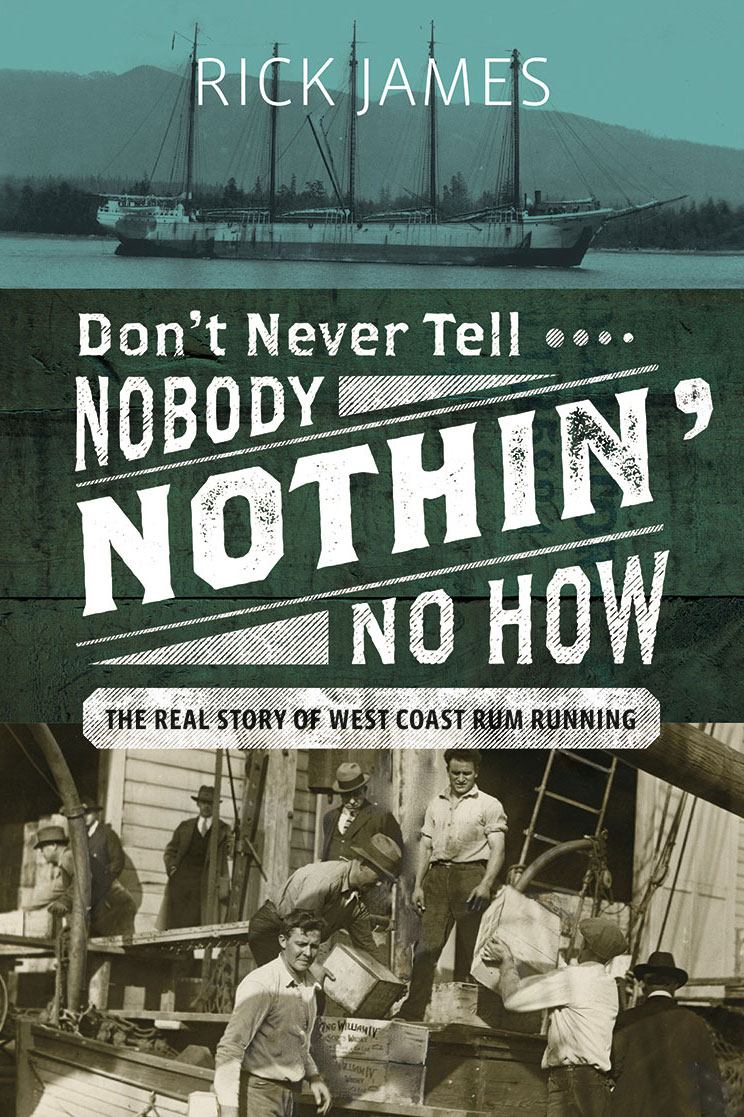

Don’t Never Tell Nobody Nothin’ No How

Don’t Never Tell Nobody Nothin’ No How: The Real Story of West Coast Rum Running

by Rick James

Harbour Publishing, 320 pages, $32.95

During Prohibition in the United States, which lasted from 1920 to 1933, a vast river of liquor flowed south across the border from Canada. The illicit cargo travelled by sea, air, and land, by boat, by high-speed motor car, by toboggan, pack animal, airplane, by every means of transport known, and by some newly invented for the purpose.

According to Rick James, in his new book Don’t Never Tell Nobody Nothin’ No How, the United States Coast Guard estimated that eighty per cent of the liquor manufactured in Canada during those years made its way across the line.

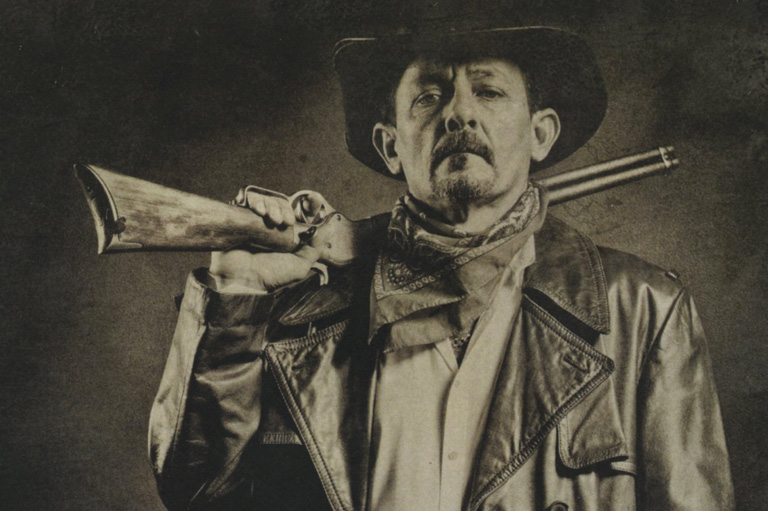

James’ authoritative and entertaining book takes a new look at one aspect of this illicit traffic, the story of the rum-runners who smuggled booze down the Pacific Coast from British Columbia into the western states. The romantic image of the rum-runner evokes a swashbuckling freelancer dodging the Coast Guard in his converted speedboat while running a few dozen crates of liquor into the secluded harbours of Puget Sound and the San Juan Islands.

This image was true enough, at least in the early days. But, as James shows, rum-running evolved into a highly organized, highly profitable business involving an elaborate network of ocean-going freighters and a web of distilleries and brewery interests that included some of Vancouver’s leading commercial families.

On the British Columbia side of the boundary, there was nothing illegal about what the smugglers were doing. As far as the Canadian government was concerned, it was the responsibility of the Americans to police their own borders. Not to mention the tax revenues that flowed into provincial and federal coffers.

James reports that in the decade from 1922 to 1932 Ottawa took in $399 million in liquor taxes, while the provinces collected another $152 million. With profits that large there was little incentive to rein in the rum-runners.

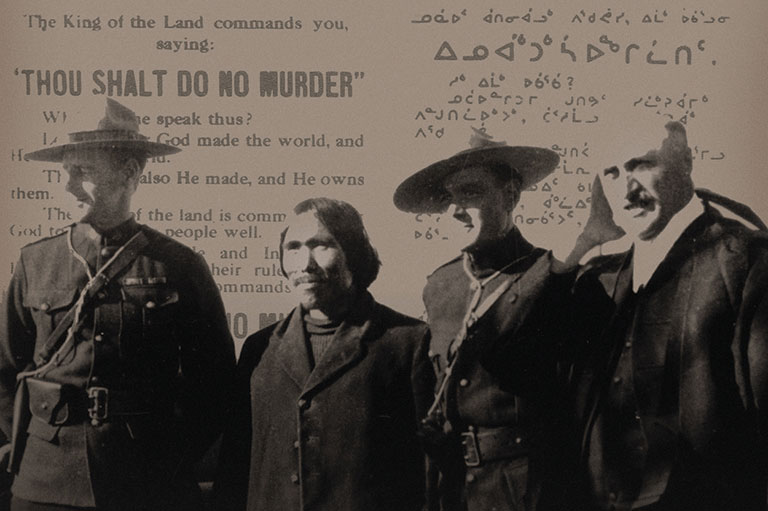

The smugglers were a tight-lipped fraternity, and James’ title refers to their reluctance to talk about their exploits. They took the old First World War slogan to heart: “loose lips sink ships.” In the words of one mariner, “rum runners made the Sphinx sound like a chatterbox.” So it is all the more impressive that James has managed to compile such a thorough account of how this clandestine operation worked.

The rum-runners may seem like characters out of an adventure movie — fun to read about but lacking gravitas. Yet, as James suggests, they made a significant contribution to the provincial economy, especially during the early years of the Depression.

One of the most prominent members of the fraternity was Captain Charles Hudson, the general manager of the largest liquor cartel. One writer called him “the true master mind of Rum Row.” It was Hudson’s contention that the rumrunners created so much business, and so many jobs, for suppliers, boat yards, engine works, and unemployed mariners that they saved the port of Vancouver. The city “was in the midst of a real depression, with logging, fishing, mining, etc. in the doldrums,” he later told an interviewer. “It took rum running to keep industry going….”

Rick James’ book makes a good case that during the early 1930s it was indeed Charles Hudson, his gang of smugglers, and the liquor industry in general that kept Vancouver’s economy afloat on a sea of illicit booze.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Our online store carries a variety of popular gifts for the history lover or Canadiana enthusiast in your life, including silk ties, dress socks, warm mitts and more!