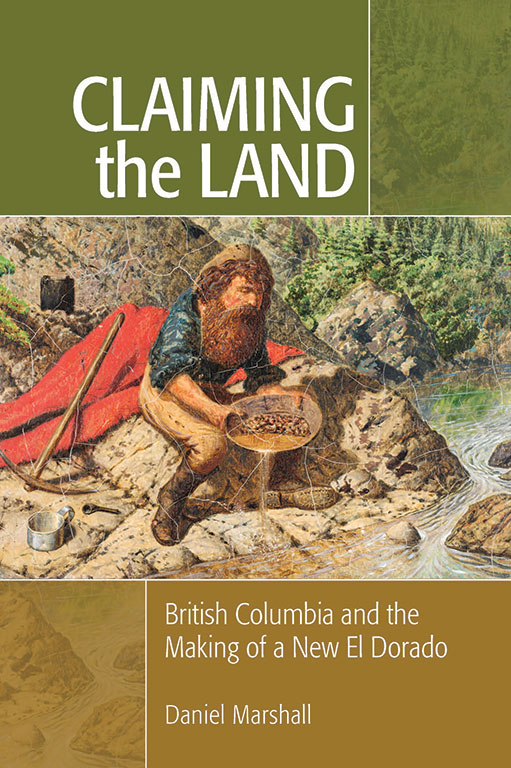

Claiming the Land

Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado

by Daniel Marshall

Ronsdale Press, 424 pages, $24.95

The names of the people who first discovered gold in British Columbia have been lost, if they were ever known at all. Several people claimed the discovery as their own, but it has been proven that Indigenous people were trading the metal before the spring of 1858, when word of gold along the Fraser River reached San Francisco.

The first gold rush in British Columbia came after the big California rush of 1849, and San Francisco had many gold seekers eager for something to do. The discovery on the Fraser River gave them a new destination, and with gold in their minds they flooded north.

Their arrival changed the area in many ways, as Victoria historian Daniel Marshall explains in his comprehensive, engaging account of a pivotal year in British Columbia and in what became Canada. The gold rush, while driven in large part by Americans, helped to pave the way for the creation of a new colony and, a decade later, for the acceptance of the region into the Canadian Confederation.

Canada’s Pacific province could easily have become part of the United States instead. It took strong resolve from Governor James Douglas and others to ensure that it remained under British control.

Marshall takes us away from the common notion of what the gold rush was all about — the idea that a few thousand men came north, made their way to the goldfields, spent time there as part of one big happy family, and headed south again.

It was uglier than that. Chaos reigned as opposing forces wrestled for control of the gold and of the land. The American border was porous, to say the least, and it was only the rugged terrain that enabled authorities to have any sort of control and to prevent the land from being overrun.

The area was, effectively, a lawless territory, quite similar to the situation in many parts of the western United States at the time. Foreign elements took the law into their own hands and met little or no opposition. Large areas of the goldfields were in the hands of self-appointed militia groups.

The Indigenous population suffered greatly. Some of the new arrivals were eager to simply exterminate the people who were already on the land and were in their way. There were several serious attempts to do just that, with Indigenous people ambushed and killed. It was war, simply put, and it was waged from the Okanagan Valley to the gold areas along the Fraser. It is shocking that these horrific slaughters are not better known, but Marshall’s efforts might help to correct and to expand upon common knowledge.

The only way to keep the peace, it seemed, was to set aside reserves for Indigenous peoples, so the gold rush of 1858 helped to shape the long-term allocation of land. (Of course, before that land was allocated, it was carefully checked to ensure that it had no obvious value.)

The gold rush led to the formal creation of the Colony of British Columbia on November 19, 1858. However, in advance of that date, Douglas already exerted authority over the region, despite no proper recognition that he could.

The year 1858 is considered the birth of British Columbia as we know it, but the events of that year have never before been considered as critically and exhaustively as they are in this book.

Marshall has, in effect, rewritten the pivotal history of the birth of the province. This book is long overdue and will form the basis for further research for years to come.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement