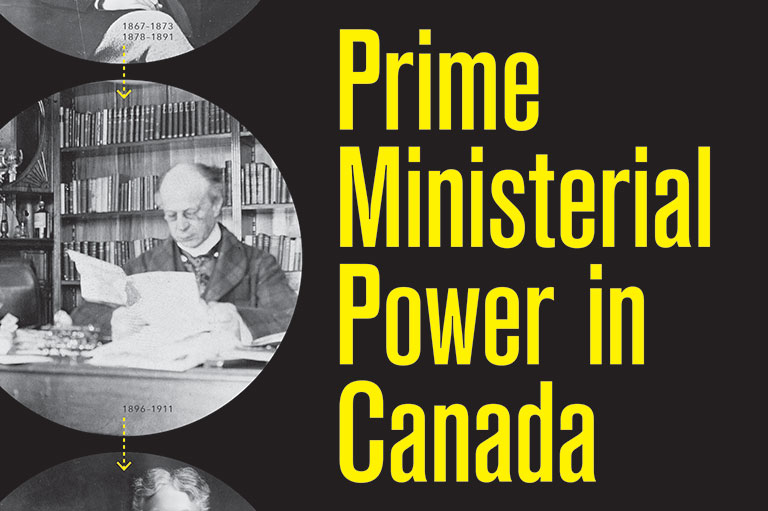

Mudflat Dreaming

Mudflat Dreaming: Waterfront Battles and the Squatters Who Fought Them in 1970s Vancouver

by Jean Walton

New Star Books,

204 pages, $24

A double review with

Dreamers and Designers: The Shaping of West Vancouver

by Francis Mansbridge

Harbour Publishing,

255 pages, $29.95

Two recently published books portray very different visions of life and living in the Vancouver area — from glass-walled homes on rocky outcroppings overlooking the sea to makeshift shacks along muddy shores and unrepaired houses in a riverbank area. They also show that battles over land and “property” have taken many forms in the course of the region’s history and development.

Francis Mansbridge’s Dreamers and Designers: The Shaping of West Vancouver includes a well-considered chapter about the Squamish people who have lived on the land across the Burrard Inlet from what is now Stanley Park since long before European settlers, vacationers, and property developers arrived. Yet, as the title suggests, the book is dedicated to and primarily inspired by the latter — who have largely achieved their dreams of realizing West Vancouver as “a place where its residents now enjoy an unusual quality of life” in a setting “characterized by magnificent (and expensive) homes and an absence of industry.”

Mansbridge has written other books about the area’s history and notes that British cultural traditions — in particular the garden city movement begun by Ebenezer Howard at the turn of the twentieth century — “laid West Vancouver’s foundations.” Already with early developer Francis Caufield, a former manager of Lloyd’s Bank of London, England, the benefits of a varied landscape and the importance of unique dwellings were emphasized.

Besides its scenic location, the area is known for often-spectacular modernist houses designed by architects Ron Thom, Fred Hollingsworth, Barry Downs, Arthur Erickson, and Geoffrey Massey, among others. Dreamers and Designers includes a chapter about these creations as well as a number of full-colour photographs that show how some homes were built to perch upon challenging terrain. Dozens of contemporary photographs by John Moir are accompanied by historic illustrations, maps, plans, and photographs.

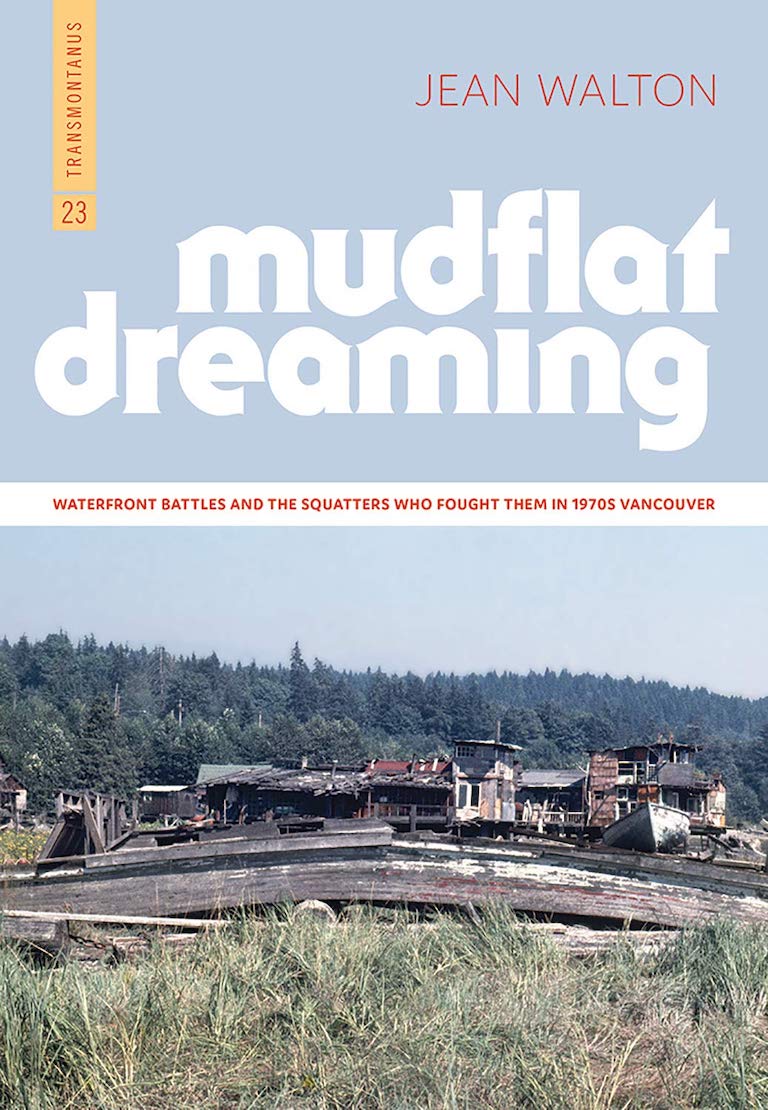

If Mansbridge’s book is an admiring recounting of the building of a largely wealthy residential city on unceded land, Jean Walton’s Mudflat Dreaming is an engaging and contemplative retelling of life in two precarious communities along the Vancouver region’s waterways. Walton is a professor of English and film studies in Rhode Island, and her book draws from documentary films that portray the struggles faced by residents of Bridgeview, a working-class neighbourhood between the Fraser River and the King George Highway in the Vancouver suburb of Surrey, and by inhabitants of the Maplewood Mudflats, a shifting intertidal space between municipal land and federally regulated waterways on the North Shore of the Burrard Inlet east of the Second Narrows Bridge.

In the early 1970s, the period about which the documentaries tell, Walton lived as a teenager not far from Bridgeview. Along with films, Mudflat Dreaming is based on newspaper accounts, minutes of council meetings, recent interviews and conversations, and even her own diaries.

Walton’s empathy for Bridgeview residents and their attempts to improve their lives and homes in the face of an intransigent mayor and council — who were more interested in removing homeowners to allow new development — is as evident as the affinities she discovers between two seemingly very different communities. She writes that, “while the residents in Bridgeview longed for the amenities” enjoyed by homeowners in nearby neighbourhoods, “the hippies on the Maplewood Mudflats seemed to spurn the trappings of suburban life.”

The NFB’s film about Bridgeview is entitled Some People Have to Suffer and was named after words spoken by a Surrey alderman. In looking back to 1970s Vancouver, Walton discovered not only “a long history of squatters along the city’s waterways” but also two documentaries about the ragtag assemblage of shacks and floating homes in the mud flats.

One film opens with idyllic scenes of waterfront living that are interrupted when the North Vancouver District mayor insists, “this cannot continue.” The mud flats hosted artists, long-time residents, various “counter-cultural types,” and others seeking an escape from the struggles of modern living — such as neurophysiologist Paul Spong, who had studied whales at the Vancouver Aquarium but whose position ended after he determined that they “had become depressed in captivity” and suggested that they be set free.

Mudflat Dreaming also tells about Robert Altman’s experimental 1971 feature film McCabe & Mrs. Miller, whose frontier-style sets were partly built by craftspeople from the mud flats and which was filmed nearby. Most of the book’s black-and-white images are stills from the various films.

Walton writes of a “fragile grace” that allows charmed ways of living to endure while a world in love with cement and uniformity threatens to foreclose upon both the dreams and their dreamers. “Well-formed concrete truly does bring a ramshackle city into the modern age,” she writes wryly in regard to a promotional film touting the benefits of a machine for producing low-cost street curbs in formerly down-at-heel Vancouver neighbourhoods. “But the mudflats films presented a life voluntarily lived on the mud as a direct refusal to have any truck with concrete of any kind.”

Can anyone truly realize their dreams for life and home? In different times and locations, and with very different senses of purpose and wonder, many people in the Vancouver area have achieved their own kinds of graceful living, while others have continued to struggle.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement