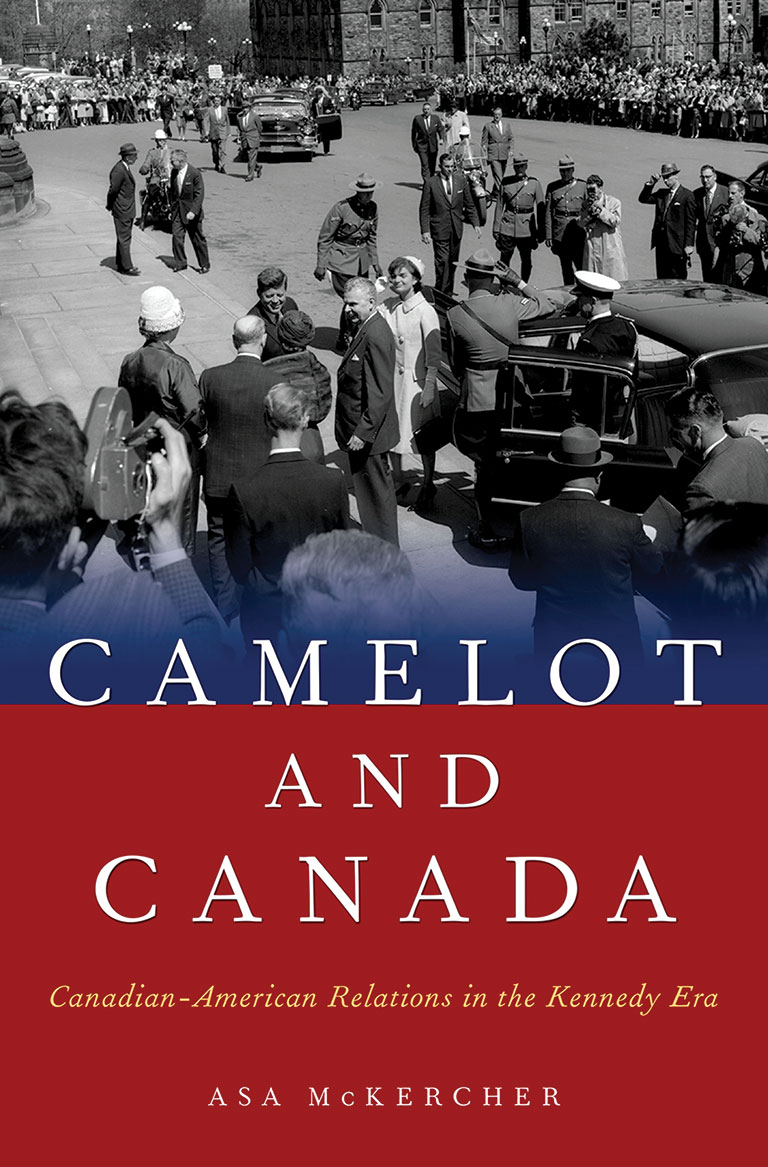

Camelot and Canada

Camelot and Canada: Canadian-American Relations in the Kennedy Era

by Asa McKercher

Oxford University Press

310 pages, $78

John F. Kennedy knew little about Canada before becoming the United States president in 1960, other than that his northern neighbour was a loyal ally. He assumed that Canadians would continue to be faithful after he came to power — and Canadians would indeed come to adore him. The glamorous, striking, and inspiring Kennedy was even ranked by Canadians in December 1962 as the “man they admired most” in the world. That was no easy pill to swallow for Canada’s prime minister, John Diefenbaker, who had ended the long Liberal dynasty in 1957 with his calls for change and fresh ideas, as well as by leading and occasionally embodying a new fierce nationalism.

While Kennedy and Diefenbaker were Cold War warriors, they came from different generations and, over time, grew to dislike each other intensely. Diefenbaker bristled at Kennedy’s easy ways, youth, and wide appeal as well as his inclination to take Canada’s support for granted. The Canadian prime minister felt that he, as leader of a country becoming more confident and sure of its place in the world, did not have to engage in strenuous efforts to get along with the American president. He was wrong, and relations with Washington deteriorated steadily as Canada continued to trade with Communist Cuba and China and refused to be rushed to decide whether to accept nuclear weapons.

Diefenbaker had many reasons to dislike the American president, not the least being his prickly annoyance over Kennedy’s mispronunciation of his name — “Diefenbawker.” Even more galling was Kennedy’s close relationship with the likeable and knowledgeable Liberal leader of the opposition, Lester B. Pearson. At one low point, Diefenbaker threatened to blackmail Kennedy over a lost document.

Asa McKercher dissects this unravelling relationship in Camelot and Canada, a work of deep scholarship that draws upon newly uncovered records in multiple archives in Canada and the United States. There is much that is new here, with important correctives and nuances to the accepted narrative, even though the text occasionally bogs down in official government briefings and accounts, and there is too often a shortage of dates to situate the reader.

Relations between Diefenbaker and Kennedy were fatally damaged after the mutual mishandling of the Cuban Missile Crisis. During that nearly apocalyptic showdown, Kennedy felt betrayed by Diefenbaker’s slowness in providing overt support, and Diefenbaker felt that Kennedy had showed him too little respect. The climax to this vitriol came during the April 1963 Canadian federal election, when the Kennedy administration worked hard to undermine Diefenbaker and to aid Pearson, who ultimately ousted Diefenbaker from power.

While Camelot and Canada is firmly grounded in the history of the Kennedy era, one cannot help but draw parallels to recent Canadian-American relations. The history of Pearson and Diefenbaker provides lessons on how Canada’s politicians need to stand firm while appearing flexible, and on how to raise concerns and worries through established back channels rather than the splash and scratch of media and social media.

There has been political tension and even personal animosity between individual prime ministers and presidents, but these disagreements have been relatively few considering the daily test of sharing the same continent. More often, there is understanding and even empathy in Ottawa and Washington for the important relationship that has been built upon a long history of mutual respect and shared history — all of which extends far deeper than any single administration or government.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement