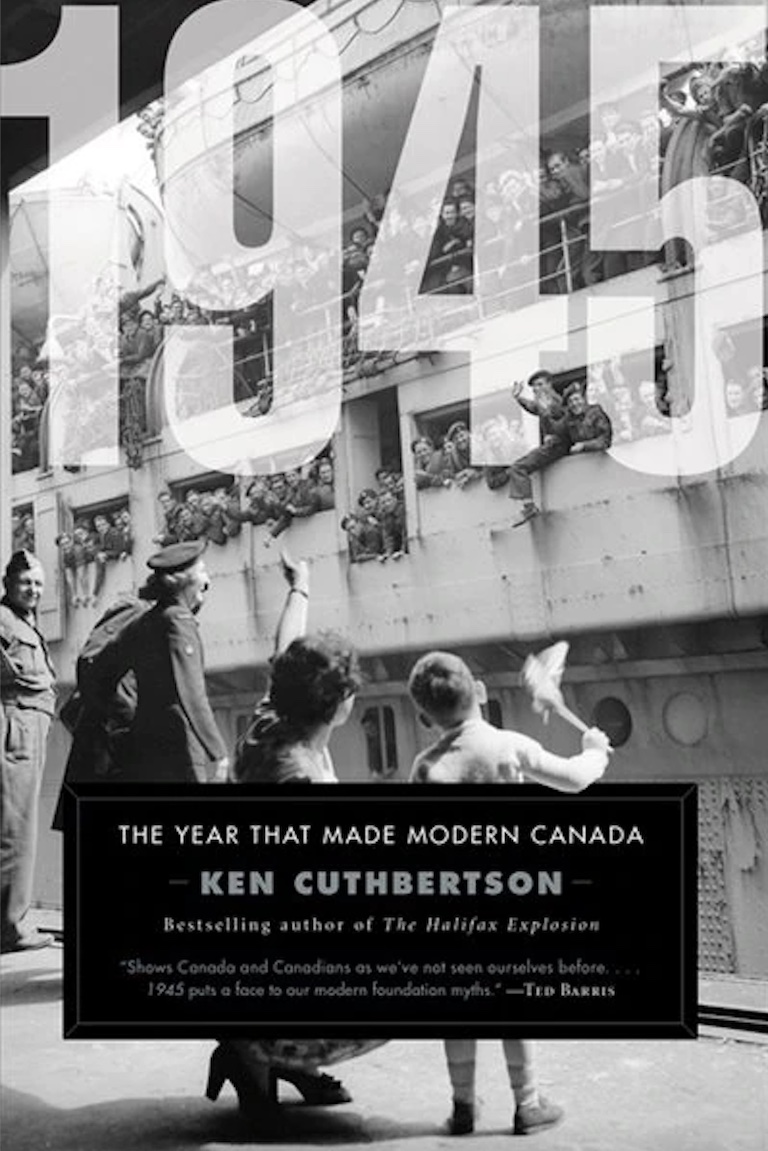

1945

1945: The Year That Made Modern Canada

by Ken Cuthbertson

Patrick Crean Editions,

404 pages, $34.99

For Canada, the year 1945 was in many ways as important for the beginning it represented as for the ending it marked. The Second World War howled to a conclusion, extinguished in the flash of the atomic bomb over Hiroshima. Canadian troops came home to fill the universities and streamed into a welcoming labour market. Their return set off both the baby boom and thirty years of unparalleled economic expansion. Ken Cuthbertson foreshadows Canada’s postwar future in his meticulously researched 1945, and he uses the events of that year to underscore the nation’s progression from backwater colony to a modern and progressive industrial nation.

Cuthbertson begins his chronicle with a Canadian soldier, Captain “Hal” MacDonald of Saint John, New Brunswick, spending New Year’s Eve of 1944 hunkered down in a battered farmhouse in Holland, soothing an infected tooth with shots of whisky. In Ottawa, still wearing the small-town ambience of its frontier beginnings, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King is alone at Laurier House, having enjoyed “a pleasant interlude” on the phone with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. King then had no way of knowing “that for Canada six years of war would soon come to an end and that going forward this country would be forever changed.”

With the stage set, Cuthbertson relates how this white-dominated and predominantly Christian country finished the war, celebrated VE day with riots in Halifax when liquor stores ran dry, rewarded its veterans with a bonus of $7.75 for every day they spent overseas, and put fifty-three thousand of them through university tuition-free. The first of its postwar tycoons, Edward Plunkett Taylor, launched Argus Corporation, the country’s first conglomerate, while King beat off the threat of the socialist CCF party by promising Canada a “new social order.”

Brief profiles of the authors, hockey players, politicians, and businessmen who would shape postwar Canada enliven 1945. A strength of the book is Cuthbertson’s ability to meld back story with foreshadowing the future. We learn of Maurice “Rocket” Richard’s humble boyhood along with his record fifty goals in fifty games in 1944–45, just as we learn about Taylor’s Argus Corporation eventually descending into bankruptcy in 2008 after its acquisition by Conrad Black.

This is a book that abounds in boosterism and that would have benefitted from more critical analysis. Cuthbertson notes that Canada was “a youngster as nations go,” having “won its independence from Britain” in 1867. Actually, Canada remained all but a colony well into the twentieth century; it was denied the right to conduct foreign policy, and its equality with Britain was not recognized until the Statute of Westminster in 1931. Its highest court remained Britain’s Privy Council until 1949, and the bitter 1960s fight for a distinctive Canadian flag bore testimony to the colonial mindset of many politicians.

Cuthbertson concedes that Canada’s economy was resource-driven, pridefully observing that Canadian-mined and -refined uranium fuelled the Hiroshima atomic bomb. Nothing is mentioned of the fact that we had no say in its use. 1945 is also silent on such socially regressive practices as capital punishment; eight Canadians were hanged that year. Canada in 1945 was not a place of comfort or tolerance for such beleaguered minorities as gays, Japanese Canadians, or Indigenous peoples.

But these are minor observations regarding a book as panoramic and engaging as 1945 or an author as conscientious as Cuthbertson. He is right on in his emphasis on Canada as a nation dedicated to business, hockey, and politics. Industrialist Taylor earns twenty mentions in the index, Maurice Richard twenty-seven, and Prime Minister King more than seventy. Cuthbertson reminds us that 1945 was a “momentous year, one like none other in the history of Canada or the world.” King’s diary entry for January 1, 1946, tells how he spent New Year’s Eve: telephoning friends, listening on the radio to the Peace Tower carillonneur, and communing with dead relatives. “I shall always feel that 1945 was the best year of my life,” he wrote.

In 1945, Ken Cuthbertson has piled fact on fact to form a solidly informative, if not always exciting, account of a period in which we moved from the old Canada to the new and did so with spirit, élan, and considerable daring.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement