10 Helping Heroes

Dr. Norman Bethune (1890–1939)

China’s great friend

Virtually unknown in Canada during his lifetime, Dr. Norman Bethune continues to be revered in China as an example of selfless humanitarianism.

Born in Gravenhurst, Ontario, in 1890, Bethune seemed destined to spend much of his life on or near a battlefield. He interrupted his medical studies to serve as a stretcher-bearer in France during World War I.

Wounded by shrapnel, he returned to Canada and graduated from the University of Toronto’s faculty of medicine in 1916. With the war still on, Bethune returned to serve in England as a lieutenant-surgeon with the Royal Navy.

After the war, Bethune practised in Montreal, where he set up a free medical clinic and lobbied for universal health care. But he was restless and passionate by nature and, when the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, he left for Madrid, setting up the world’s first mobile blood-transfusion clinic.

Bethune is most remembered for the two years he spent in China during the Sino-Japanese War. He fearlessly cared for wounded soldiers and civilians amidst aggressive fighting. He built a portable surgical theatre, which he carried on two mules, and trained civilians in basic medical and surgical practices.

On November 12, 1939, Bethune died from blood poisoning after operating on a wounded soldier. The Chinese greatly mourned his loss. To this day, Chinese schoolchildren learn about “the great Canadian friend of the Chinese people.”

Advertisement

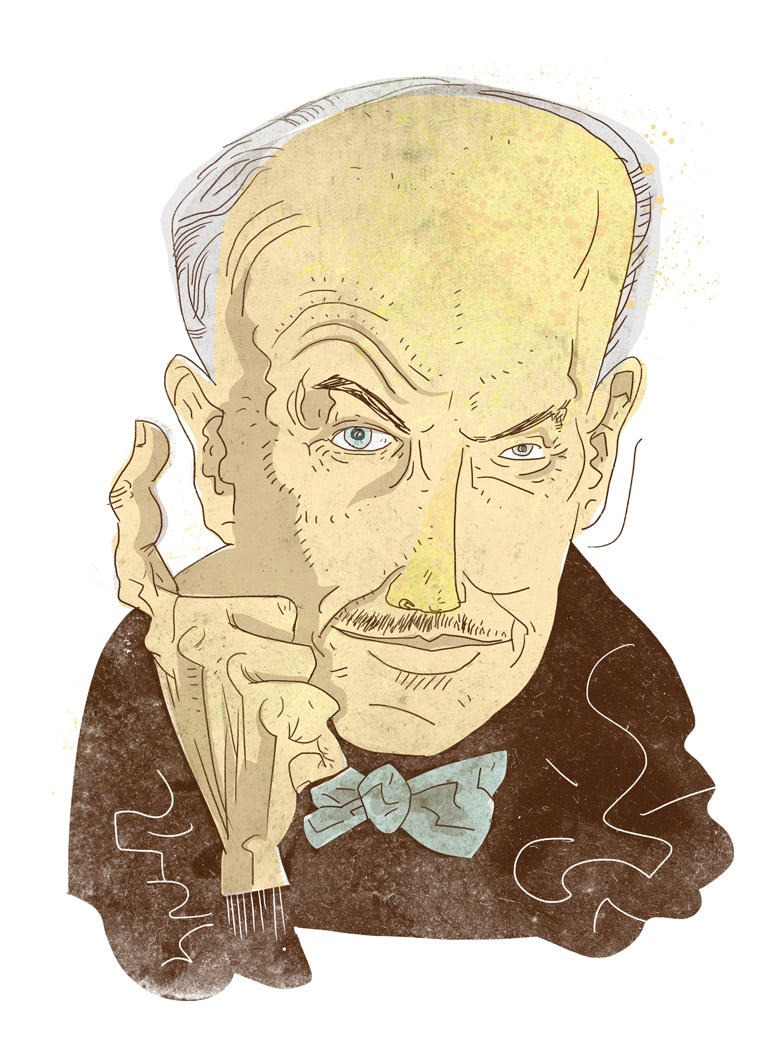

John Peters Humphrey (1905–1995)

Father of human rights

By the age of eleven, John Peters Humphrey had lost both of his parents to cancer and had had his left arm amputated after a fire. As an adolescent, his disability made him a target for bullies at his boarding school.

These difficulties seemed to strengthen his character, however. He went on to become an international human rights pioneer, drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

After distinguishing himself in private law and as a professor at McGill University, Humphrey was appointed director of the human rights division in the UN Secretariat in 1946. There, he worked closely with Eleanor Roosevelt to draft a bill that would guarantee the basic rights of all people.

The final declaration was reached on December 10, 1948, after 187 meetings and 1,400 resolutions. Roosevelt described it as “the Magna Carta of all mankind.”

For the next twenty years, Humphrey travelled extensively to ensure systems were in place to protect human rights and to establish them where they were not. He worked tirelessly to advance such causes as freedom of the press, the status of women, and ending racial discrimination.

Humphrey’s role in the universal declaration was somewhat obscured and not fully realized until the original draft was discovered many years later. In 1974 he was made an Officer of the Order of Canada and in 1988 he was awarded the United Nations Prize for human rights advocacy.

George Atkins (1917–2009)

Founder of Farm Radio

Long before the advent of the Internet, a farmer from Oakville, Ontario, created an international network to spread agricultural knowledge to the world’s poorest farmers.

George Atkins, who earned an agriculture degree at Ontario Agricultural College, started a radio and television show in his community that provided advice to local farmers. A few years later, in 1955, he began a twenty-five-year career with the CBC as a farm correspondent.

In 1975, Atkins travelled to Zambia for meetings with the Commonwealth Broadcasters’ Association. While there, he saw that farmers in developing countries needed better access to information about practical and inexpensive technology, such as fertilizing with manure or raising oxen.

Atkins launched the Developing Countries Farm Radio Network, which compiles and distributes information to farm broadcasters around the developing world. Based in Ottawa, it began in 1979 with thirty-four broadcasters and twenty-six countries. Now called Farm Radio International, it has grown to three hundred broadcasters in more than thirty-nine African countries.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Dr. Gustave Gingras (1918–1996)

Rehabilitation pioneer

His work with injured veterans of World War II launched Dr. Gustave Gingras’s career as an international expert in helping disabled people. Gingras, who had served with the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps as a neurology intern during the war, was asked by famed neurologist Dr. Wilder Penfield to oversee the rehabilitation of a group of fifty veterans in Montreal who were expected to be invalids for the rest of their lives.

Gingras brought together a team of therapists, social workers, and psychologists and pioneered many rehabilitation techniques. As a result, many of the vets were able to return to their homes and jobs. His success led to more demand for his services, and in 1949 he founded the Rehabilitation Institute of Montreal, which was fully operational by the time a polio epidemic hit in the 1950s.

Other countries soon sought Gingras’s help. He went to South America under the auspices of the United Nations to help victims of work-related accidents in the oil industry. In 1959, he went to Morocco to rehabilitate ten thousand people who were suddenly paralyzed from consuming motor oil sold as cooking oil. During the Vietnam War, he set up rehabilitation centres and ran workshops to build prosthetic devices.

At the end of his life, he suffered a neurological disorder but followed his own motto: “Never give up, and focus on remaining abilities rather than on those lost.”

Dr. Lucille Teasdale-Corti (1929–1996)

War surgeon in Uganda

As a twelve-year-old student at a Montreal school, Lucille Teasdale’s direction in life was influenced by the visit of some missionary nuns who had worked in China. Wishing to be like them and to make a difference in the world, Teasdale decided on a career in medicine. When she graduated from the University of Montreal in 1955, she became one of Quebec’s first female surgeons.

In 1961, she travelled to Uganda to help Dr. Piero Corti transform a small forty-bed clinic into a hospital. Dr. Teasdale tended to as many as three hundred outpatients each morning and performed surgeries in the afternoon, while Corti, who became her husband, raised money for the Lacor Hospital project.

When civil war broke out in Uganda in 1971, Teasdale-Corti found herself working as a war surgeon, with the hospital often under attack. In the mid-1980s, she contracted AIDS while operating on a soldier. Teasdale-Corti managed to continue working for another eleven years before passing away.

Lacor Hospital is today one of the finest in East Africa, with almost five hundred beds, three satellite clinics, and 300,000 patients annually.

Kathy Knowles (1955–)

Extraordinary storyteller

Sometimes, small actions can spark big changes. In 1989, Kathy Knowles and her family moved to Accra, Ghana, when her husband accepted a position with a Canadian gold-mining company. In their new backyard in the West African city, Knowles began a story time for her four children and their friends. Knowles soon became big news in the community, and her backyard story time quickly grew to include over seventy children.

Realizing that the children needed a proper and permanent place to read books, Knowles converted her garage into a makeshift library. Within a short time there was a waiting list for books. Knowles raised some money and, with the help of the community, bought and transformed a shipping container into Osu Library. Knowles accumulated over three thousand books, both from her own collection and donated from friends and family in Canada.

In 1993, Knowles and her family returned to Canada, but not before ensuring Osu Library could keep on running. She set up the Osu Library Fund as a registered charity in Ghana and Canada and trained community members to work in the library.

Today, Knowles continues her work with the Osu Library Fund from her home in Winnipeg. She has helped build seven libraries in Accra and more than two hundred in Africa. Many of her libraries now include adult literacy classes, child nutrition programs, and cultural events.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Craig Kielburger (1982–)

Children’s rights activist

Craig Kielburger is well-known to Canadians for starting the international advocacy group, Free the Children, at the age of twelve. He was motivated to fight against child slavery after reading about a twelve-year-old Pakistani boy who had been sold to a carpet maker at age four. Iqbal Masih escaped when he was ten but was assassinated two years later for speaking up for the rights of thousands of child labourers working in terrible conditions.

Angered about the boy’s tragic fate, Kielburger brought the newspaper article to his school. He and his classmates immediately took action; they wrote letters to world leaders, formed petitions, raised money, and increased awareness of child slavery.

Free the Children has since built over 650 schools, established rehabilitation centres to support former child slaves, founded medical clinics, and raised the awareness of millions of people all over the world.

Kielburger continues to work with Free the Children and has since co-founded two other organizations — Leaders Today and Me to We — with his older brother Marc Kielburger. The brothers jointly write a syndicated column and are bestselling authors. Both are also Members of the Order of Canada.

James Gareth Endicott (1898–1993)

Peacemaker and pariah

Socialist missionary James Gareth Endicott held views about Red China that were unpopular in his time, causing him to be reviled by top Canadian politicians and slammed in the press as “public enemy No. 1.”

Endicott was born in China to Canadian missionaries. He returned to Canada in 1910 and served with the Canadian artillery in World War I. After the war he trained as a Methodist minister and in 1925, he returned to Chungking in Szechuan, China, to begin two decades of missionary work.

Endicott became a vocal supporter of the pro-revolutionary communists during the Chinese civil war (1927–1949). His views put him at odds with the church and he was forced to resign in 1946.

Undaunted, he returned to Canada and founded the Canadian Peace Congress in 1948 and a year later played a key role at the World Peace Council in Stockholm, which fuelled the “ban the bomb” movement. In 1952, the RCMP considered him a security threat and the Canadian government threatened to try him for treason.

But Endicott carried on, maintaining his leadership of the Canadian Peace Congress for twenty-five years and dedicating his life to the international peace movement. Meanwhile, public attitudes gradually shifted. In 1982 the United Church issued an apology to Endicott, saying that the events of the past thirty years had borne out many of Endicott’s “predictions and prophetic actions on the issue of world peace.”

Paul Gérin-Lajoie (1920–2018)

International educator

As a provincial cabinet minister in the 1960s, Paul Gérin-Lajoie modernized Quebec’s outdated school system. He would later take his expertise in educational improvement around the world.

In 1970, he became president of the Canadian International Development Agency, a position he held for seven years. During that time he forged international relationships with more than seventy-five countries and developed and implemented cooperative programs with more than sixty organizations. He increased Canada’s visibility and reputation internationally while serving on many boards, including the World Bank.

After his political career, Gérin-Lajoie formed a consulting firm specializing in international cooperation. Throughout his career, education remained one of Gérin-Lajoie’s top priorities. In 1977, he founded the Paul Gérin-Lajoie Foundation, an organization dedicated to improving child education and eliminating illiteracy in developing countries. At the heart of its mission was the belief that education is an essential human right.

At the time of this writing, Gérin-Lajoie continued to work with the foundation, which also educates Canadian youth about international development. He died in June 2018.

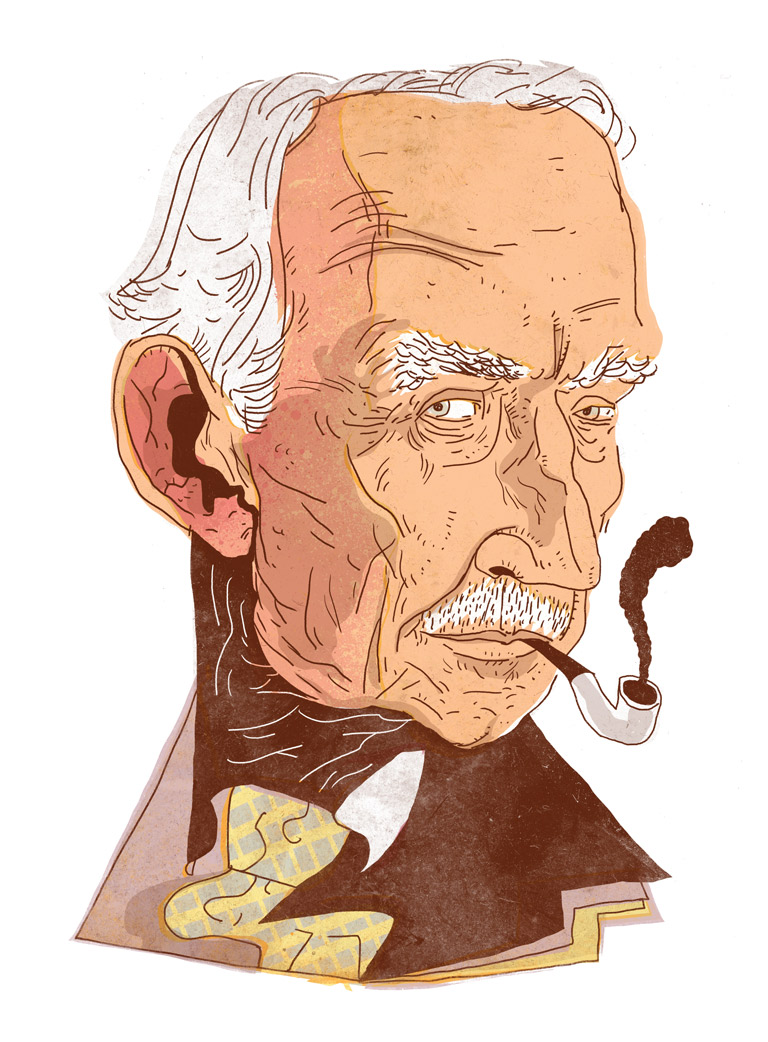

Maurice Strong (1929–2015)

Global environment leader

From his humble roots as a prairie boy growing up during the Great Depression, Maurice Strong went on to become one of the most important leaders in the global environmental movement.

The bright, hardworking Strong completed high school by age fourteen. At nineteen, James Richardson & Sons – a leading brokerage firm — hired him as an oil and mineral resources specialist. From there, Strong excelled in the resources industry and by 1961 he was president of Power Corporation of Canada.

Strong gained the attention of then-Prime Minister Lester Pearson, who invited him to serve as deputy minister of external aid, a department which later evolved into the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). His work with CIDA gave him insights into the complexities of development and he soon became a powerful voice in environmental politics.

In 1972, he became an international name after being elected to head the newly formed United Nations Environment Program. Twenty years later, Strong led the UN Conference on Environment and Development — the Earth Summit — in Rio de Janeiro.

More than 120 heads of state attended the conference, which laid the groundwork for greater environmental protection and responsibility. Following the summit, Strong took an active role in carrying out the initiatives and programs developed during the conference.

At the time of this writing, Maurice Strong lived in China, where he continued to work closely with the resource and technology industries and as an advocate for the environmental movement. In November 2015, Strong died in Ottawa.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.