The Person Behind the Persons Case

Not much is known of Lizzie Cyr. Her arrest record indicates she was five foot six, with brown eyes and a dark complexion. She was born in Canada and described as a mix of First Nations and European descent. “Wife” is listed as her occupation, “vagrant” (or prostitute) as her criminal occupation. Her mug shot shows a woman who looks friendly but shy, maybe a little scared. However, in profile, eyes downcast and a defeated expression on her face, Cyr looks much older than her twenty-nine years.

-

According to Calgary Police records, Cyr was arrested four times between 1913 and 1917, twice for vagrancy and twice for drunkenness. Her 1916 arrest for vagrancy ended in a sixty-day sentence with hard labour.CALGARY POLICE SERVICE INTERPRETIVE CENTRE AND ARCHIVES

According to Calgary Police records, Cyr was arrested four times between 1913 and 1917, twice for vagrancy and twice for drunkenness. Her 1916 arrest for vagrancy ended in a sixty-day sentence with hard labour.CALGARY POLICE SERVICE INTERPRETIVE CENTRE AND ARCHIVES -

Houses of ill repute located near railway track approximately fifty metres north of the railway bridge over Bow River in Calgary.GLENBOW ARCHIVES / NA-673-9

Houses of ill repute located near railway track approximately fifty metres north of the railway bridge over Bow River in Calgary.GLENBOW ARCHIVES / NA-673-9 -

Alice Jamieson, Calgary, 1913. Jamieson’s first legal appointment, in 1914, was as judge of a juvenile court.GLENBOW ARCHIVES / NA-2315-1

Alice Jamieson, Calgary, 1913. Jamieson’s first legal appointment, in 1914, was as judge of a juvenile court.GLENBOW ARCHIVES / NA-2315-1 -

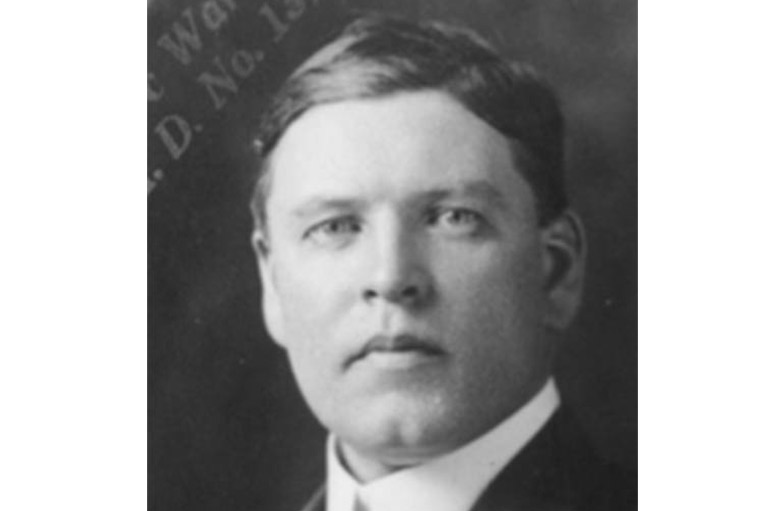

John McKinley Cameron in 1918. Though the Nova Scotia-born lawyer was a Conservative and a member of the Calgary establishment, he was also a vigorous advocate of social justice and the rights of all Canadians.GLENBOW ARCHIVES / NA-4691-6

John McKinley Cameron in 1918. Though the Nova Scotia-born lawyer was a Conservative and a member of the Calgary establishment, he was also a vigorous advocate of social justice and the rights of all Canadians.GLENBOW ARCHIVES / NA-4691-6 -

Nellie McClung, Alice Jamieson, and Emily Murphy, 1918. McClung and Murphy, along with Louise McKinney, Irene Palby, and Henriette Muir Edwards, were the Famous Five.CITY OF EDMONTON ARCHIVES/EA-10-2070

Nellie McClung, Alice Jamieson, and Emily Murphy, 1918. McClung and Murphy, along with Louise McKinney, Irene Palby, and Henriette Muir Edwards, were the Famous Five.CITY OF EDMONTON ARCHIVES/EA-10-2070 -

CC-BY Douglas Sprott / flickr

CC-BY Douglas Sprott / flickr

She was turned in to police by John James Ryan on May 17, 1917. Though they had known each other for a number of years, Ryan and Cyr had most recently met six days earlier. After admitting she was broke and had no place to stay, Ryan allowed Cyr to spend the night at his place. They had intercourse, for which he paid her ten dollars. The next morning, Saturday, she became sick and remained at Ryan's place for another night. By Sunday, May 13, Ryan had grown tired of her company and kicked her out. Some days later, Ryan himself became ill – with gonorrhea. Having had the disease seven years earlier, Ryan did not go to a doctor for diagnosis but went straight to the drugstore for medicine. The next day he sought out Cyr and offered her a deal: if she paid for his treatment, he wouldn't turn her in. Cyr refused and Ryan reported her to the police. She was arrested the same afternoon. She had no money in her possession.

Cyr was charged under Section 238 (a) of the Criminal Code, which states:

Every one is a loose, idle or disorderly person or vagrant who,-

a) not having any visible means of subsistence is found wandering abroad or lodging in any barn or outhouse, or in any deserted or unoccupied building, or in any cart of wagon, or in any railway carriage or freight car, or in any railway building, and not giving a good account of himself, or who, not having any visible means of maintaining himself, lives without employment.

It was a tawdry and not uncommon incident that should have passed into history unnoticed, but through a combination of circumstance and personality, the arrest and trial of Lizzie Cyr became the inciting event that would lead, more than a decade later, to one of the most famous decisions in Canadian jurisprudence: the Persons Case of October 18, 1929, which stated once and for all, that women were indeed considered persons under the law. Ironically, the case involved one woman denying another her right to a defence.

Cyr's trial took place on May 18, 1917, the day following her arrest. There was no jury present: though an indictable offence, vagrancy was not considered a serious enough crime to be tried by jury. Hence, the only buffer between the accused and the absolute power of the police magistrate was her defence lawyer, John McKinley Cameron.

Born in Pictou, Nova Scotia, in 1879, John McKinley Cameron received his law degree from Dalhousie and was called to the bar in 1904. For a number of years he practised law in Nova Scotia as counsel of the Mine Workers' Union, but in 1911 (some sources say 1909) he and his family moved to Calgary. Cameron had started his own firm there by 1914, which focused primarily on criminal law. An intelligent man with an encyclopedic knowledge of the Criminal Code, Cameron soon earned a reputation for himself as a brilliant, though eccentric, lawyer. He enjoyed the simple pleasures in life, which included, on occasion, sleeping in the loft of his garage with his hunting dogs. He took a relaxed approach to the established legal profession and often appeared in court wearing mismatched, wrinkled suits and rubber boots. However, his irreverence towards dress did not extend to his work. Cameron took his career very seriously. Motivated by more than money and prestige, he often took cases where remuneration from the client was neither likely nor possible. Many of his clients came from the lower rungs of the social ladder, including miners, Chinese immigrants, gamblers, bootleggers, and prostitutes.

It is not surprising then, that in the spring of 1917, his path crossed with that of a young woman named Lizzie Cyr (alias Waters).

Cameron was on the offensive from the start, stating first of all his belief that the charge was unfounded: “There are hundreds of women in the city of Calgary who do not earn any money and who are not vagrants,” and he entered a plea of not guilty. “I want further to object that your Honour has no power or jurisdiction to try this case.”

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Ryan was the first to testify; Cameron was aggressive yet witty, using Ryan's own testimony to put his virtue and his credibility in question.

Q. When did you consult a doctor about it [gonorrhea]?

A. I did not consult a doctor about it. When it started running I went to the drug store and bought some medicine.

Q. When was that?

A. The day before yesterday.

Q. What doctor did you see?

A. I did not see any doctor. I went to Mr. McGill and told him what was the matter and he said, “I know the medicine you need.”

Q. Are you still running at large?

A. I am not running at large. I have got a home and working every day.

Q. Got a family?

A. No I am not married. I rent a home and I stay at home every night.

Q. You are going to behave yourself and leave the girls alone until you are cured?

A. Yes I am.

Cameron points out here that Ryan was as much of a risk to society as Cyr when it came to the spread of disease. Not only was this the second time he had been infected, but Ryan was also a self-admitted john. By sleeping with other prostitutes he could spread the disease to them, and they in turn would help spread it throughout the city of Calgary.

Q. Outside of getting diseased- was there any other objection to her?

A. The objection was I did not want to keep a prostitute in the house and she did not want to leave.

Q. You took the prostitute to your house?

A. Yes, for one night.

Q. And after one dose of gonorrhea you thought you should not have a prostitute in your house… You are sure you are absolutely virtuous and could not have got it from any other woman?

Advertisement

Here Cameron questions the provenance of the disease. Ryan was obviously not the most virtuous of men and presumably had interacted with prostitutes before: how could he know for sure he got the disease from Cyr? Ryan’s response to this was that Cyr had been the only woman with whom he had been “doing business,” to which Cameron wryly responded, “You are very moderate.”

The examination continued:

Q. What do you do for a living?

A. I work.

Q. Are you working now?

A. Well, if I was not here I would be working this afternoon at the Central Methodist Church.

Q. I think you will contaminate the church. Are you still going to work for the church?

A. Yes, the Adjutant phoned me down at the Salvation Army.

Q. Did you reveal to him that you had gonorrhea?

A. No, I did not.

Q. What work are you doing down there, because we do not want an epidemic to break out in the church … She is charged that on the 17th day of May, she had no visible means of support. You don’t know that she is a decent married woman?

A. I have seen her around.

Q. It takes two to have sexual intercourse. Are you a decent man?

Ryan, becoming irritated, responded: “I guess I am working and earning my living…”

Cameron may have made a fool of Ryan at the trial, but Ryan was no idiot. He knew very well that, being a male with a home and a job (at a church no less), the odds were in his favour. Otherwise, it is unlikely he would have reported Cyr to the police, since in doing so it was necessary for him to incriminate himself. He was as familiar as Cameron about society's fears of venereal disease and its prejudices towards certain groups of people.

While the authorities as well as the public had largely tolerated vagrancy and prostitution in Calgary in times gone by, by the 1910s an era of social and moral reform had arrived. Social purists and moral reformers in the form of church groups, citizens' leagues, the YWCA, and the National Council of Women pressured politicians and police alike to do something about the level of vice existing within the city. Calgary’s police force, heretofore undermanned and poorly trained, was improved under the direction of police chiefs Thomas Mackie (1909-1912) and Alfred Cuddy (1912-1919). Cuddy especially inaugurated a strict clean-up campaign, closing all bawdy houses on the outskirts of the city. Besides concern and outrage over the perceived moral degeneration of the population, another factor that influenced the public attitude towards prostitution was the fear of venereal disease. Though diseases such as syphilis and gonorrhea affected all levels of society, they were primarily associated with “immoral” women. Historian David Bright writes: “In the resulting measures of coercion, inspection and prosecution, the individual rights of those suspected of infection frequently took a back seat to the alleged security of the nation.” Such attitudes, as well as prevailing discriminatory feelings toward Métis and aboriginal women, were all working against Cyr when she was arrested.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Throughout his examination Ryan brought up the fact that Cyr was infected with gonorrhea and therefore posed a danger to the public at large: “She is not in a healthy condition to be running around and carrying that disease.” He accused her of leaving her husband and, further, he implied she had an indecent relationship with a Chinese man, an association that, given the anti-Oriental prejudice of the time, would have lowered Cyr's status even more. When Ryan had gone to her place the day before the trial to get payment, he encountered this man:

A. I knocked at the door and it was locked. A few minutes after she opened the door and a Chinaman was in the room with her.

Q. The Chinaman was there for the laundry ?

A. The door was locked.

Q. Did you warn the Chink against her?

A. No, when the Chink seen me he walked out.

Q. You don’t know if he took anything away with him or not?

A. No, they were in the room together and the room was locked.

Cameron did not pursue this further, but instead questioned Ryan again on his disease:

Q. How do you know you have gonorrhea. Did you consult a doctor?

A. It started running.

Q. What started running?

A. My penis started running. After a man gets one dose he knows a little about it.

Q. You did not consult a doctor?

A. No...

William Symons, the arresting officer, was sworn in next. Cameron questioned Symons about the circumstances surrounding the arrest. Apparently Cyr had admitted to taking the ten dollars; however, there was no proof of the provenance of the disease. “You do not know anything about the facts in this case. You don't know whether she gave him gonorrhea or anything?” Cameron asked. “No,” Symons responded, “only what he told me himself.”

Here the judge, Alice Jamieson, cut in abruptly: “Lizzie Cyr, I sentence you to six months hard labour at MacLeod.” This sudden statement cut Cameron's examination short. Naturally, he took objection. Cyr had had no chance to defend herself and Cameron was outraged. “I shall see that your decision is overruled!” he flung at Jamieson.

Jamieson's decision seems hasty and harsh, particularly when the reason for her appointment as police magistrate in 1916 was to ensure fair trials for female delinquents. Historian John MacLaren writes,

These women [magistrates] brought with them a different set of beliefs and values to the role of magistrate than their male colleagues. These views were reflected in their approaches to the problem of vice in general and the treatment of wayward females, including prostitutes, in particular. Faced as they were with the exploitation of female juveniles by procurers and pimps they felt outrage at the seemingly irresolute, unfair and insensitive way in which the criminal law was applied by male law police officers, prosecutors and magistrates.

However, this was not to say female magistrates were tolerant of vagrant women by any means. In fact, MacLaren cites Jamieson’s treatment of Lizzie Cyr as an indication of this. While female magistrates often sympathized with young or first-time offenders, “hardened” or unrepentant offenders were dealt with more severely. Magistrates such as Jamieson and Emily Murphy (the only other female police magistrate in the Commonwealth) generally felt that such delinquents would benefit from enforced confinement. Perhaps Cyr’s conviction record convinced Jamieson she required a harsh sentence for her reformation. In the four years prior to her arrest in 1917, Cyr had been arrested twice for drunkenness and once for vagrancy. The harshest sentence she served was for the former vagrancy charge: sixty days hard labour. For her latest vagrancy charge, Cyr received the maximum term of imprisonment that could be given under the Criminal Code. (In one respect she was lucky-Jamieson could have slapped an additional fifty-dollar fine on top of her prison term!

Of course, Jamieson’s job could not have been easy. Cameron’s attack on her authority was likely not the first barb she’d felt, nor would it be her last. Indeed, Cameron himself would again question her qualification for the job in another trial, just seven months following Cyr’s. This must have been a source of considerable stress and anxiety for Jamieson. An interview published in the Calgary Daily Herald March 13, 1920, quotes her:

Being the first woman magistrate was no position to excite envy, I assure you. I had to fight down a good deal of prejudice on the part of certain members of the legal profession and the police department. When I first assumed my duties in the police court with cold shoulders greeting me on every hand, I said to myself “I don’t know why I ever came here – I don't have to do this,” and then I drew myself up and said, “Well I’m here and I'm here to stay.”

Maybe Jamieson was determined to prove that she could do her job and do it well; maybe she was simply trying to be the best judge she could be: sometimes harsh, but always impartial.

Ultimately, as David Bright remarks, prostitution and vagrancy in 1917 were “crimes of status.” It was not necessary to prove a specific incident in court; it was enough to have simply demonstrated that the accused led a certain type of life. This is evident in Cyr’s case. In the course of his testimony, Ryan pointed out several things to demonstrate Cyr led this type of life: she was infected with gonorrhea, characterizing her as a loose woman; he had “seen her around,” implying she was a repeat offender and likely a hardened prostitute; she did not have any money; she had left her husband and therefore was without a means of support; and, finally, she associated with other undesirables of society. Obviously it was clear to Jamieson that Cyr led the kind of life that warranted a conviction and a prison sentence, even though this decision was based solely on hearsay.

John McKinley Cameron hated to lose. In fact, he appeared before the Alberta Supreme Court of Appeal more times than any other barrister between 1912 and 1932. Maybe he was a small-minded chauvinist or maybe it was something more complicated. But after losing the Cyr case in Alice Jamieson’s court in the spring of 1917, Cameron appealed not only her decision but also her right to sit as magistrate. On June 14, Alberta Supreme Court Justice David Scott dismissed the application, though he himself had reservations about the right of a woman to hold office: “While I entertain serious doubt whether a woman is qualified to be appointed to that office, I am of the opinion that the legality of such an appointment cannot be questioned or inquired into on this application.” So Cameron filed another application with the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of Alberta. Justices Beck Stuart, C.J. Harvey, and J.J. Walsh dismissed it as well. Justice Stuart appears to have had no doubts about a woman’s qualifications to hold office:

I therefore think that, applying the general principle upon which the common law rests, namely, that of reason and good sense as applied to new conditions, this Court ought to declare that in this Province, and at this time in our presently existing conditions, there is at common law no legal disqualification for holding public office in the government of the country arising from any distinction of sex. And in doing this I am strongly of opinion that we are returning to the more liberal and enlightened view of the middle ages in England and passing over the narrower and more hardened view which possibly by the middle of the nineteenth century had gained the ascendance in England.

With this decision, Alberta became the first province to legally endorse women’s rights, as persons, to hold office. JUDGES FIND THAT MRS. JAMIESON IS LEGALLY APPOINTED announced the Calgary Daily Herald November 26, 1917.

However, Canadian policy was not consistent with that of Alberta. Emily Murphy, Henrietta Edwards, Nellie McClung, Louise McKinney, and Irene Parlby, more commonly known today as the Famous Five, challenged the Supreme Court of Canada to follow Alberta’s precedent. On April 24, 1928, however, it ruled against Alberta, stating that women were not legally persons. Unwilling to back down, the Five took their case over the head of the Canadian legal system to the British Privy Council. Britain overruled Canada’s decision on October 18, 1929, stating that, once and for all, women were indeed considered persons under the law.

Jamieson carried on as police magistrate throughout the fight to win women’s rights as legal persons under the law. In 1931 she settled into a comfortable retirement, two years after the Persons Case was won. Cameron continued his illustrious career as well. He became most famous for his defence of Italian bootlegger Emilio Picariello and his accomplice Florence Losandro (see the Beaver, June/July 2004), accused of murdering Constable Stephen Lawson in 1923, a case he lost, despite his firm belief that they were innocent. Cameron continued defending cases into the 1930s. He died in 1943.

While undoubtedly a victory for most Canadian women, there is a loser in the story of the Persons Case. Jamieson’s fitness to judge was upheld, which meant her decision to sentence Lizzie Cyr was also sound. Cyr served her six months at the NWMP barracks in MacLeod, in a crowded and poorly ventilated cell, susceptible to diseases such as typhoid, bronchitis, and measles. It is unclear what kind of hard labour she served. There is a record of Lizzie Cyr working as a waitress at the King Edward Hotel in Pincher Creek, a small community just southwest of Fort MacLeod, in 1922. There were other Cyrs here – perhaps she rejoined her family. After this, Lizzie Cyr, a.k.a. Waters, quietly disappears from history, a not uncommon fate, one suspects, for a penniless Métis prostitute.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!