The Mothers of Confederation

Canadian history alludes to women of the last century only incidentally, yet our country owes an enormous debt to those not immortalized with the “Founding Fathers.” Our “Founding Mothers” led lives filled with endless toil, too numerous pregnancies, cumbersome dress and second class citizenship, but by the end of the nineteenth century a dramatic, courageous tale of “women’s sphere” began to unfold.

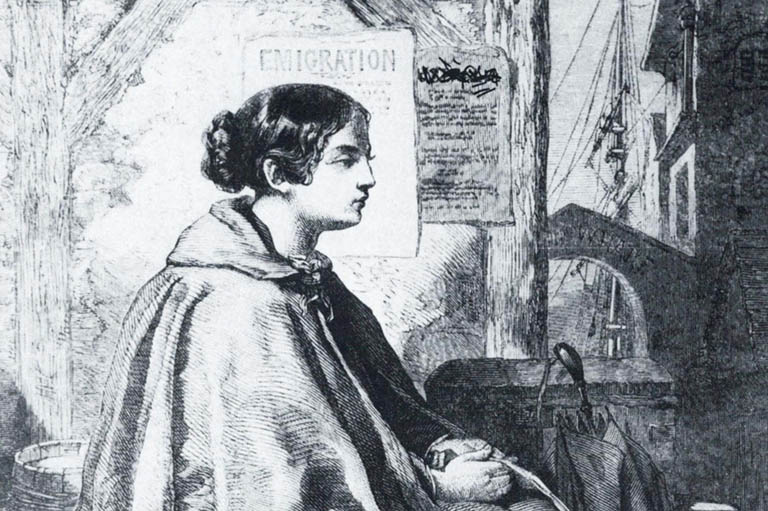

The story began before confederation when there was a great demand for female labour. Newspapers, promoting the planned mass immigration, praised women as “invaluable as a sympathetic companion, an economical manager, an actual helpmate in the farm work, as a mother of future citizens and as a standard-bearer of civilization.”

“I believe that never was a country better adapted to produce a great race of women than this Canada of ours nor a race of women better adapted to make a great country.”

Emily Murphy

Our Founding Fathers, not oblivious to the importance of the female role in the future of Canada, were very cautious about the quality of women immigrants. Although the Election Act of the Dominion of Canada stated that “No woman, idiot, lunatic or child shall vote,” there was a steadfast belief that women were the cornerstone of family and nation. The values they would pass on to the young, it was unanimously agreed, should be British values since Canada “would be a nation that was British in outlook and character.”

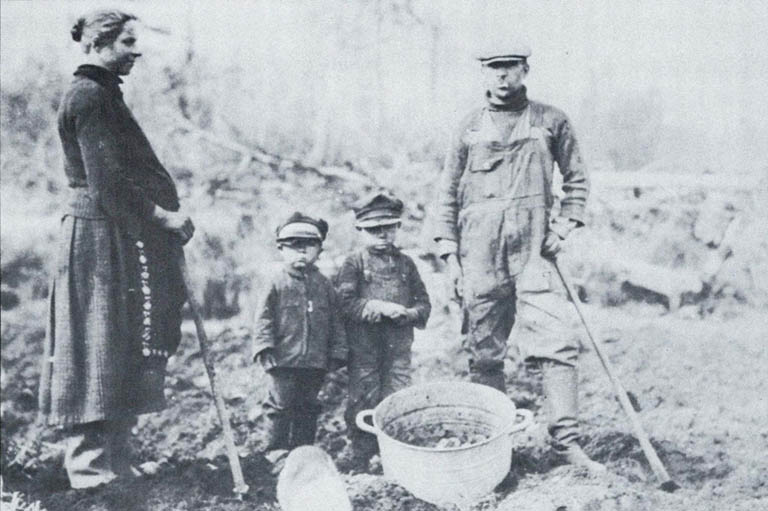

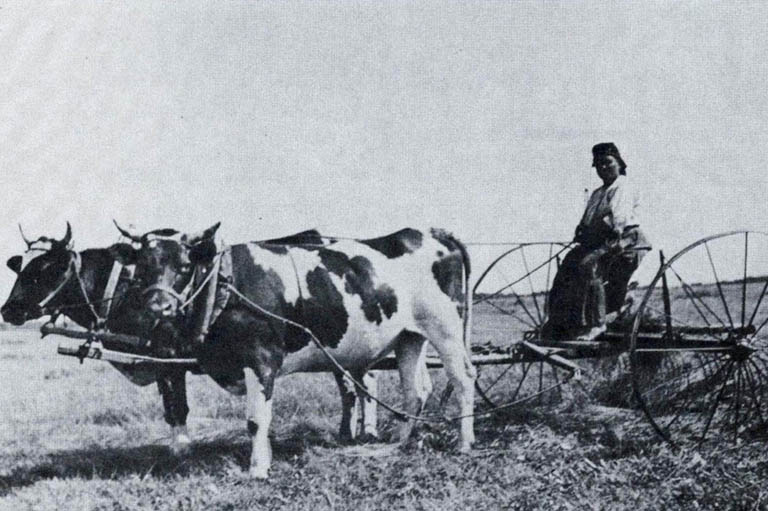

Long before this search for the ideal Canadian mother began, colonial women had cleared land, worked as loggers, owned and operated mines, hunted for meat and trapped for fur. They did this while raising families and they often kept journals about their pioneering lives. The 1820s saw a significant number of women working in “non-traditional jobs” such as silversmith, woodworker, coachmaker, lumberjack and mortician. “A shorthanded country” wrote one observer, “could not disdain womanpower.”

Despite this past history of woman’s work, Canada’s late-nineteenth-century servant recruitment campaign began looking for the “best classes” of British women. Applicants were scrutinized to determine their moral character, respectability, job performance, attitudes, intelligence and physical health. These women were assured that as servants their work would not be difficult since Canada boasted labour-saving machines and varnished woodwork. In fact, the life of work left little leisure time. “It was nearly five o’clock before I had done my room, changed my working dress and was ready to enjoy my one hour ‘off’ during the day…,” recalled one woman who had been a domestic servant in pioneer Alberta.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Most female immigrants embarked on the voyage to Canada with the belief, as one expressed it, that “they would lead not unpleasant lives at starting and speedily rise to better things.” When they arrived, the women were sorted into groups by destination and taken to temporary shelters or hostels. Other women usually supervised the grouping of these new servants onto trains headed for distribution centers in Montreal, Winnipeg, Calgary, Regina, Edmonton and Vancouver. The uncomfortable and overcrowded trip from Montreal to Vancouver took five days, and rumours spread that women disappeared from the trains, no doubt into “white slavery.”

Most found their way to be placed as servants in Canadian homes. For their services they often received as little as five dollars per month, with room and board.

Motherhood was thought to be the goal and primary social function of every Canadian woman. This socialization process, molding Canadian girls into potential wives and mothers, began early. They were encouraged to play with dolls until they were teenagers. According to The Young Lady’s Book of 1876, games such as chess were not allowed because “Chess is not a game much played by ladies as it requires rather more thought and calculation than women possess.” The author of this book was a woman.

Many children were not allowed card games since card playing resembled gambling, but reading was encouraged. The Young Lady’s Book, subtitled “A Manual of Amusements, Exercises, Studies and Pursuits,” was meant to fill girls’ leisure time. The Holiday Album For Girls of the same period contained moral stories of “ideal” little girls—thoughtful Maggie who helped an old lady off the train, Eva who was crippled but still managed to be happy and naughty Esther who would come to no good because she stayed in bed after she had been wakened by her mother. Meanwhile boys were reading about the glorious adventures of other lads in gold mines, on whaling ships, sailing the seven seas and mountaineering.

When children grew up and married the household cradle was rarely unoccupied, even though infant and maternal mortality was alarmingly high. The situation was not helped by primitive obstetric practices.

Once babies were delivered they were bathed and their umbilical cords rubbed with tallow and a light dusting of nutmeg. Babies were then dressed in layers of clothing, since swaddling had gone out of fashion in Canada by the nineteenth century. One last item was sometimes added if superstitious parents could afford it—a coral bead which was hung around the baby’s neck. This was a charm to ward off the evil eye.

Gynaecology had developed into a medical specialty by the late 1800s. These “experts” considered themselves knowledgeable, not only in the medical realm of the female body, but related their unfounded expertise to female sexuality, female social roles and “female spheres.”

Who would argue with the male experts? So women devoted their lives to children and found that motherhood led them from the cradle to the kitchen. Cooking became women’s duty by birth and this formidable job included making all staples such as bread, butter, pickles, catsup and preserves. Fruits and vegetables were inconveniently canned on the hottest August days when the produce reached suitable ripeness.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Bread was made from wheat flour, with corn, rye and buckwheat being used occasionally. Pumpkins were an important mainstay, used for soups, pies and “pumpkin sass”—a type of molasses. Later apples replaced pumpkins as a major pie material, and by the end of the century plants imported from England produced gooseberries, raspberries, strawberries and currants.

Cooking and canning did not stop at the family’s needs, for meals often included farm hands, especially at harvesting time.

Ella Sykes, a visiting English journalist, recorded this story of a prairie woman: “In shearing time, I had to cook for fifteen men… they needed five meals a day… I just got into the way of thinking nothing but how to get through the day’s work.”

Besides cooking, every housewife had her family formula for making ink, floor polish, silver cleaner, whitewash, rat poison, boot spray, shampoo, cold cream, tooth powder, hair tonic, soap and candles. Roots and herbs were stored for sickness because mother was often the family “doctor” with traditional remedies for most minor ailments.

Family life centred on the kitchen and the fireplace. The kitchen was at the back of the house so that the smell travelled outside. Not only were kitchen smells thought unpleasant, but it was believed they carried disease. Hot roasted coffee beans were carried around the house to kill the odours.

The front doors were reserved for strangers and special visitors, while all other traffic flowed through the kitchen. The floors were usually plain wood until the late 1800s when linoleum was invented. Tables were covered with oilcloth. The zinc sinks, home-helps and wives soon discovered, were difficult to clean.

Cooking was done traditionally on the fireplace and the poor continued to use this method long after the rich could afford huge iron ranges that burned coal and wood. These ranges, kept going all day and night, were a prized household possession. Fireplaces were not readily replaced by central heating and many saw the new heating discovery as the potential cause of family breakdowns. Fireplaces had not only been the cooking area, but the place where families gathered to keep warm, discuss the day’s happenings, and share time together.

Almost everyone agreed on the favourite household treat—ice cream. It took a long time to prepare since a hot custard of milk, sugar, egg and vanilla had to be made first and then churned and cooled. Cream was put into a tin pail that was set in a large wooden pot packed with ice and salt. Willing helpers turned the handle for hours, adding new ice and salt from time to time.

It would seem that the cult of domesticity had enmeshed Canadian women in never-ceasing household chores. Ladies’ magazines, edited and published by men, romanticized the role of the farmer’s wife. In actuality, loneliness, alienation and despair were repeatedly expressed in written records kept by farming women. Statistics show disproportionate incidents of mental breakdown among that era’s women.

The story of “Women in the 1900s,” amazingly, does not end in domestic detail and despair. The great changes occurring in Canada by the end of the century affected women profoundly. Inventions such as the sewing machine and the bicycle brought not only labour saving devices but acceptable sport and leisure. Cities provided the important opportunity for women to meet and organize.

The first generation of Canadian social feminists appeared as early as 1860. As women moved from being predominately household servants into factories, school rooms and nursing homes, organizations began to develop. Local church groups, and benevolent societies grew with the towns and gave women the chance to move beyond their homes.

Motherhood and cooking, however, were still considered “women’s sphere” and the groups proceeded with great caution and assurances that family balance would be upheld. Lady Aberdeen, wife of the Governor-General, an experienced diplomat, pointed out that Canadians needed “careful handling” on the “woman question.” The National Council of Women of Canada, formed in 1893, could only advance after repeated guarantees of its loyalty to the ideal of a domesticated and conciliatory womanhood.

So these women, anxious to take an active part in society, concerned themselves with “acceptable” projects such as working girls, urban housing, children’s recreation, and cultural improvement.

Medical care was another cause to which the National Council of Women of Canada directed its efforts. Lack of medical attention inflated the infant and maternal mortality rates. The Victorian Order of Home Helpers, a forerunner of the Victorian Order of Nurses, was founded in 1897. Having been taught techniques of household sanitation, the nurses set out for remote Canadian dwellings, bringing much-needed medical knowledge of sanitation and infant care. Still, they had to justify their jobs as nurses in the light of the ideal of domestic Canadian womanhood. This was accomplished by signing a contract denying independence. The contract stated that “a respectable and acceptable nurse was an ideal lady who showed wifely obedience to the doctor, motherly self-devotion to the patient and a firm mistress/servant discipline to those below the rung of nurse.”

Women’s groups knew they were treading on dangerous ground and facing hardened ideas about women, the family and the Canadian nation. They moved out of their homes into groups and activities with continuous caution and verbal justifications that their actions would in no way impede what they knew was their role and position in life. They even reassured the Canadian public with contrasts between “feminine” Canadian women and “argumentative, mannish, ill-mannered, fast” Americans.

Change had begun, as this editorial in the Victoria Times of 1893 verifies: “Ten years ago people were much more content to lead a vegetable life, troubling their heads but little over what are now considered to be the burning questions of the day. There was a stifling air of laissez-faire in those times, and a strong tendency towards the suppression and ridiculing of all women’s higher aims and ambitions; but in this fin-de-siècle much of that is changed, and the ability of the gentler sex to cope with and successfully master many of the deeper problems of life is becoming an established and recognized fact.”

These courageous women’s groups succeeded in opening not only the eyes of many Canadians, but eventually the doors of the universities and professions. Confederation women are not in the famous “Founding Fathers” picture, but without their endless physical toil the country could not have developed. Against great social pressure, they did the ground-work for the suffrage movement as well as for other profound social changes, the effects of which are still being felt today. To forget the details of their lives is to forget an important part of Canadian history.

If you believe that stories of women’s history should be more widely known, help us do more.

Your donation of $10, $25, or whatever amount you like, will allow Canada’s History to share women’s stories with readers of all ages, ensuring the widest possible audience can access these stories for free.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Related reading

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!