Chocolate Strike

They can’t do this to us! It's just not right!”

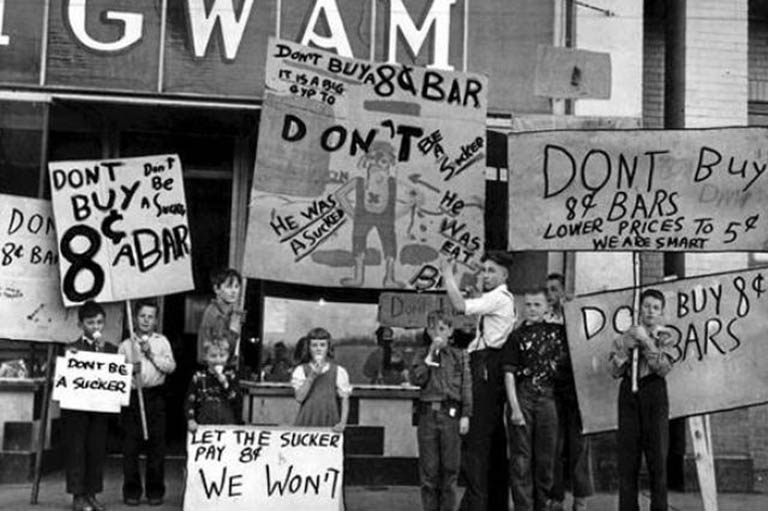

Fifteen kids had gathered in front of Thomas’s father’s shop. Thomas stood on a chair, calling for silence. It was 1947, and in the two years since World War II had ended, kids had grown accustomed to adults protesting rising food prices. No one had expected this latest price hike, though.

“What we need is a plan,” Thomas said in a loud, clear voice. “No one can afford to pay eight cents for a chocolate bar. That’s almost double the five cents they used to cost!”

His little sister, Maggie, sighed. Other kids whispered to each other, but all eyes were on Thomas. He wished the class bully, Chuck, could see him now. Chuck was one of the main reasons Thomas had called this meeting, after all. Chuck was determined to turn everyone against Thomas, just because his father’s shop was selling eight-cent chocolate bars.

“Kids in other towns are already fighting the price hike,” Thomas informed the group.

“The newspaper said they’re making signs and marching in front of stores that are charging eight cents for a chocolate bar.”

Maggie’s eyes opened wide, and Thomas looked away. He hated the idea of protesting in front of his father’s shop, but something had to be done.

“If kids in other parts of the country are protesting,” Thomas said, focusing on his best friend, Jeffrey, at the back of the group, “it’s time we do the same here in Victoria.”

“We should go to Ottawa and tell the government what we think!” shouted Frank Brown, raising a fist in the air.

“Frank,” Jeffrey said, “how will we get all the way to Ottawa when we can’t even afford an eight-cent chocolate bar?”

Frank shrugged and offered a sheepish smile. “Just a thought.”

“I have another idea,” said Thomas, “one that adults use all the time. We’ll boycott. That means we all have to stop buying chocolate.”

“What?” asked a small kid in a checkered shirt. “But we came here because we want to buy chocolate!”

“Thomas is right,” said Jeffrey, pushing his glasses back on his freckled nose. “If no one’s buying any chocolate bars, the shopkeepers will have to sell them cheaper, just to get rid of them.”

“We’ll make big signs,” Thomas said, “and a few kids outside every candy shop will tell everyone going inside that they shouldn’t buy chocolate.”

Maggie frowned, and Thomas knew she was wondering how this plan would affect their father’s shop. But Thomas believed this was the only way.

If kids saw him defending his father, they’d turn against him for sure. He clapped his hands and asked if anyone had questions. Then he took down names for protest shifts.

Protest

“I got the cardboard!” Thomas arrived breathless at Jeffrey’s house. His father had given him a million chores that afternoon, so he’d had to pedal hard to make it on time. No way was he going to be late for the sign-making!

“Everyone’s around back,” Jeffrey said. “George brought the paints, and Jill has a bunch of paintbrushes. Mum’s got the whole back porch covered in newspaper so we don’t drip, and Al, Lynne, and Harry are here, too.”

Everyone was crammed onto the porch, wielding paintbrushes and talking about the best slogans for their signs. “Don’t buy eight-cent bars. Go on strike!” Harry shouted.

“I’ve got a better one,” said Al. “I thought it up in math class. Come on folks, don’t be a drip, ’cause eight-cent bars are just a rip!”

Everyone laughed, but Jill thought maybe they should tone things down a bit. “How about, Be helpful: don’t buy eight-cent bars?”

“Nah,” said Thomas. “We’ve got to be forceful. Down with the eight-cent bars. Up with five-cent bars! That’s what I’m putting on mine.”

Talk went on for a long time, paint flew and dribbled, and in the end, all the kids were smudged and grinning, with enough signs to march in front of every chocolate-selling shop in Victoria.

Storming the Legislature

“Have you heard?” Jeffrey asked a few days later as he and Thomas grabbed their snacks for recess. “There’s going to be a march on the Legislature. This afternoon. After school.”

Thomas’s jaw dropped. Sure, the protests in front of the shops had been going well — most customers had smiled or congratulated the kids for sticking up for themselves. But protesting on the street was one thing; talking to politicians was quite another. Would they listen? Or would the kids get in trouble for wasting their time?

“Don’t tell me you’re chicken, Tommy,” said Chuck, ambling up behind Jeffrey.

Oh, why couldn’t Chuck just leave him alone? Thomas pulled himself up tall and locked eyes with him. “I’ll be there,” he said.

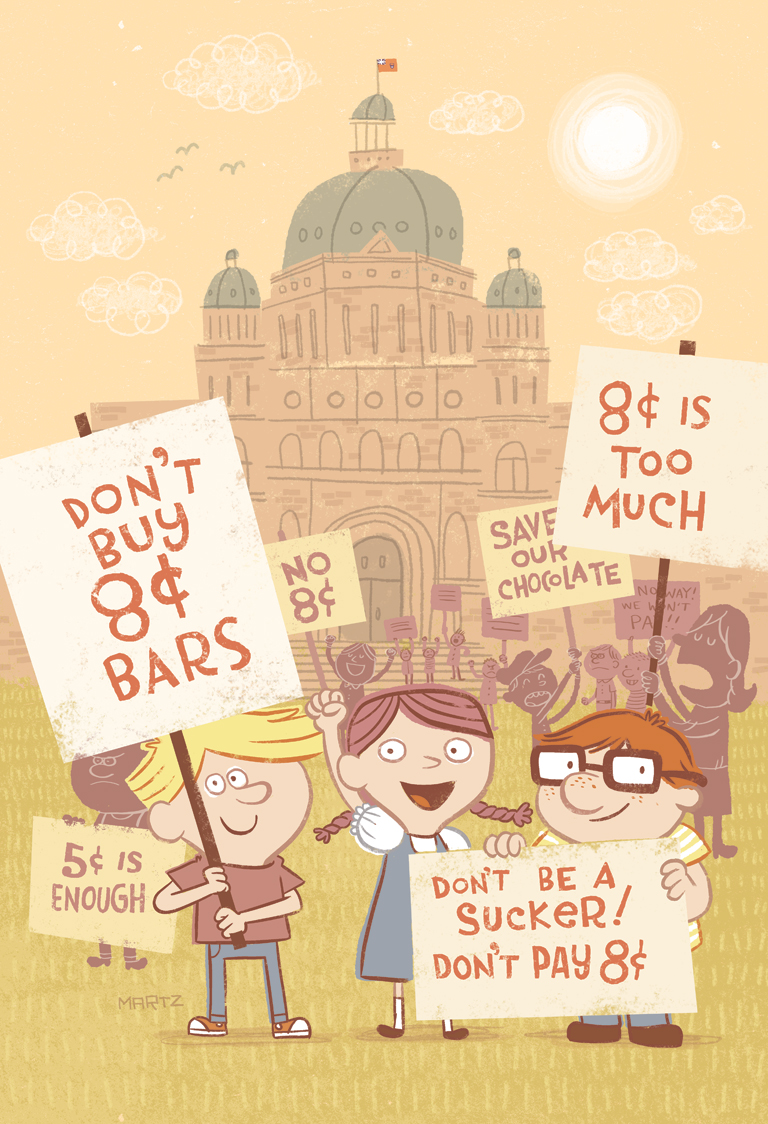

Hours later, Thomas and his schoolmates made their way to the Legislative Buildings, waving their signs. Their school was closer than any other in town, but they didn’t have to wait long before other children flooded the lawn in front of the buildings, too.

Thomas kept a close eye on Maggie and her friend Jo, who looked as nervous as he felt. If anything happened to them, he’d be in trouble for sure.

Within half an hour, over two hundred kids were marching and shouting, making such a racket that a man in a blue uniform poked his head out the front door.

“Five cents is common sense!” Thomas yelled.

“We want five-cent bars!” shouted Jeffrey.

“Let’s go talk to the government!” called a kid in a newsboy cap.

The whole crowd shifted, and Thomas took a deep breath as he felt himself swept toward the big, main building along with everyone else. They pushed open the doors and flowed into the bright, polished halls.

“What are you going to do about chocolate prices?” the boy in the cap demanded of the first man they saw.

“How do I know?” The security guard stood with his hands on his hips in front of the rotunda, blocking their path. “I’m just supposed to keep you out of here!”

“Too late!” Maggie called. The crowd surged past, up the stairs with the stained glass windows, toward the gallery.

As they moved, other men and a few women jumped back to watch from the doorways. Someone asked a man in a suit what he planned to do about the price hike, and Thomas barely caught his answer as he sailed by: “Uh, um, well now, I guess we’ll have to give that some thought. Er… are you supposed to be in here?”

More security guards were coming now, and janitors, and up ahead someone was shouting, and the kids at the front of the group paused and began to back up. Soon the whole crowd was retreating down the stairs, cheering as they poured out of the building. The adults were shaking their heads but smiling, and Thomas was both relieved and proud. When a man with a camera appeared outside, Thomas was the first to spot him.

“This way, everyone!” he called. “A photographer wants to take our picture!”

Children, signs, and bicycles crowded onto the front steps of the large stone building, the same spot where photographers always took pictures of really important visitors.

As the crowd shouted, “We want five-cent bars,” the photographer snapped one picture after another.

Making the News

“Hey, look at this!” Jeffrey came running into the classroom the next day, waving a newspaper. He spread it out on one of the desks, and his classmates crowded around.

“That’s me,” said Thomas, poking a finger at the photo. Everyone leaned in closer, eager to find their own faces and almost busting with excitement from the attention their protests were getting. Maybe if they kept at it, they really would put an end to the price hike.

“And did you hear about Thomas’s father?” Jeffrey asked. “He’s going to sell the rest of his chocolate bar stock at five cents!”

The whole class cheered — even Chuck. And Thomas felt a bit like a hero.

The Power of Protest

The national children’s strike over chocolate bars really did happen. It started in Ladysmith, British Columbia, on April 25, 1947, and spread across the country.

Kids everywhere boycotted the eight-cent chocolate bar, and hundreds in Victoria stormed the Legislature on Tuesday, April 29. On May 3, kids all across the country paraded in the streets to protest the price hike.

The strike ended abruptly on May 4, 1947, after the Toronto Telegram published an article claiming that communists were involved in the strike and were exploiting the children to advance their political cause.

Many adults were alarmed by the possibility, and the schools withdrew their support for the protest. The strikes stopped, but not before the children achieved something remarkable.

All across the country, they had made their point. Shopkeepers found ways to continue selling chocolate bars to kids for five cents, despite the new prices.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement