Park Prisoners

-

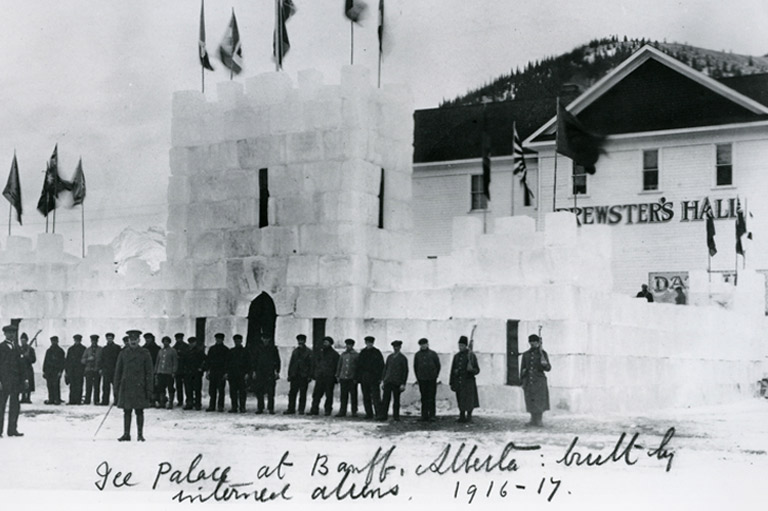

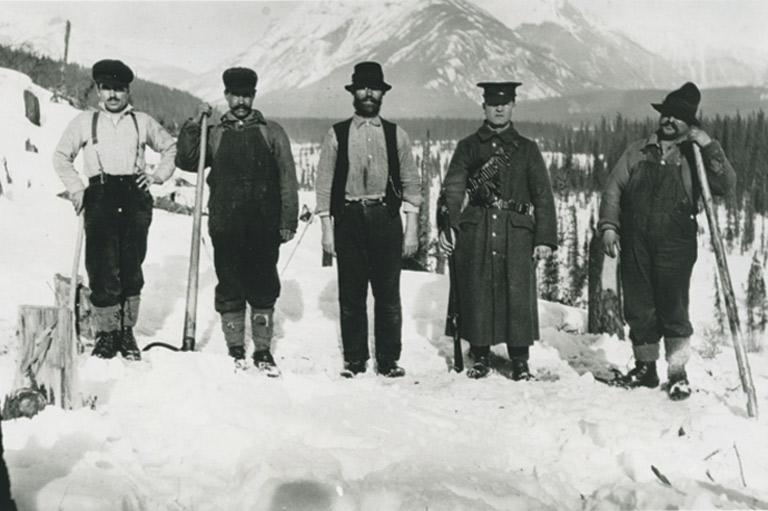

Interned aliens at the ice palace they built at Banff, Alberta, during a winter carnival in 1917.Archives of Alberta / A4837

Interned aliens at the ice palace they built at Banff, Alberta, during a winter carnival in 1917.Archives of Alberta / A4837 -

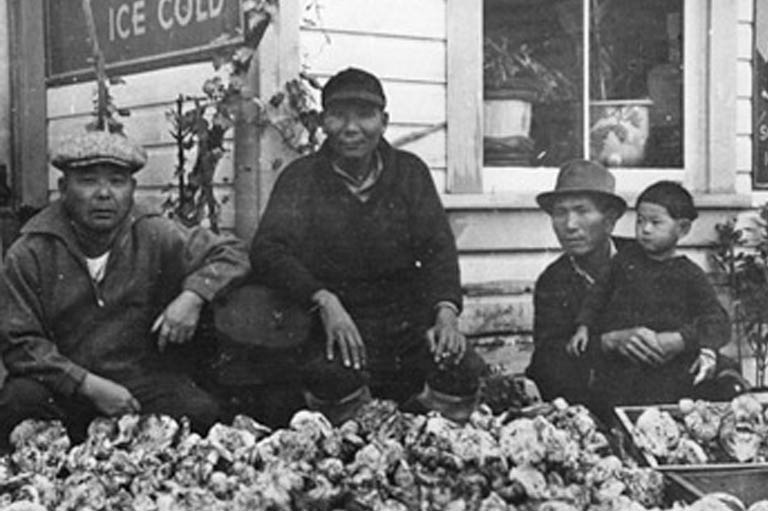

Relief camp dining hall workers pause before serving a meal. Workers were usually well fed.Canadian Park Service, Western Regional Office, Webster Collection

Relief camp dining hall workers pause before serving a meal. Workers were usually well fed.Canadian Park Service, Western Regional Office, Webster Collection -

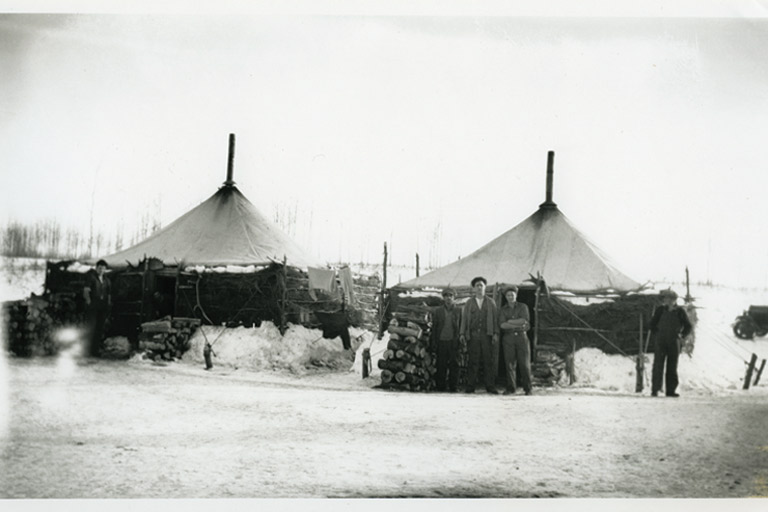

Internees outside their sleeping tents at Elk Island National Park, Alberta, in the early 1930's. The destitute men banked hay bales around their tents to keep warm.Canadian Park Service, Western Regional Office, Webster Collection

Internees outside their sleeping tents at Elk Island National Park, Alberta, in the early 1930's. The destitute men banked hay bales around their tents to keep warm.Canadian Park Service, Western Regional Office, Webster Collection -

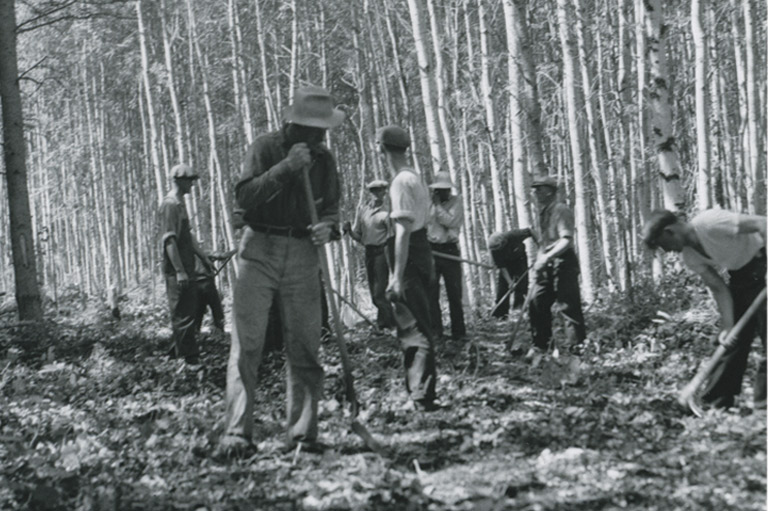

At Prince Albert National Park, Saskatchewan, conscientious objectors clear fire trails during the 1940s.Library and Archives Canada / C131651

At Prince Albert National Park, Saskatchewan, conscientious objectors clear fire trails during the 1940s.Library and Archives Canada / C131651 -

German prisoners of war at Whitewater Camp in Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, where they were held from 1943 to 1945.Courtesy of Josef Gabski

German prisoners of war at Whitewater Camp in Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, where they were held from 1943 to 1945.Courtesy of Josef Gabski -

Alternative service workers pose under the entrance to Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba.H. Sawatzky

Alternative service workers pose under the entrance to Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba.H. Sawatzky -

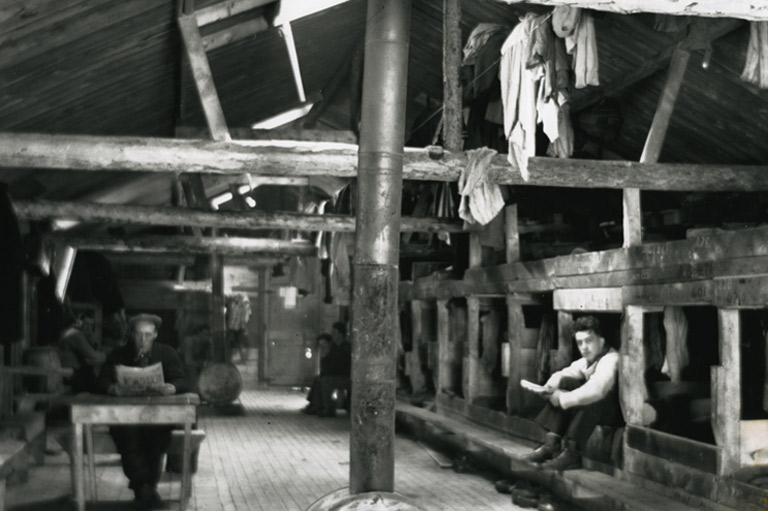

A bunkhouse for interned relief workers at Riding Mountain Park, Manitoba, during the early 1930s. The men slept two in a bunk.Parks Canada, Western Regional Office, Webster Collection

A bunkhouse for interned relief workers at Riding Mountain Park, Manitoba, during the early 1930s. The men slept two in a bunk.Parks Canada, Western Regional Office, Webster Collection -

A German POW with a dugout canoe built by the prisoners at Whitewater Camp in Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, during the Second World War.Courtesy of Josef Gabski

A German POW with a dugout canoe built by the prisoners at Whitewater Camp in Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, during the Second World War.Courtesy of Josef Gabski -

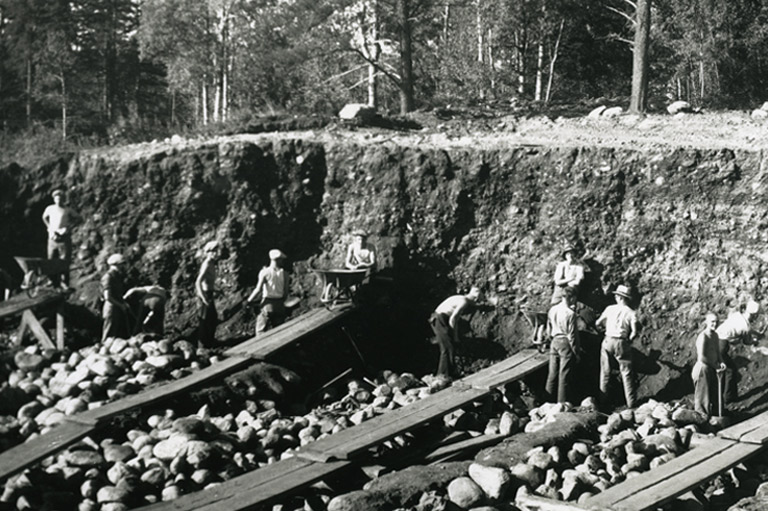

Internees working at a gravel pit in Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, in August 1933.Parks Canada, Western Regional Office, Webster Collection

Internees working at a gravel pit in Riding Mountain National Park, Manitoba, in August 1933.Parks Canada, Western Regional Office, Webster Collection -

Second World War Japanese internees arrive at the Yellowhead-Blue River Road project, a 200 km highway between Jasper, Alberta and Bluer River, British Columbia.Parks Canada, Western Regional Office, Webster Collection

Second World War Japanese internees arrive at the Yellowhead-Blue River Road project, a 200 km highway between Jasper, Alberta and Bluer River, British Columbia.Parks Canada, Western Regional Office, Webster Collection -

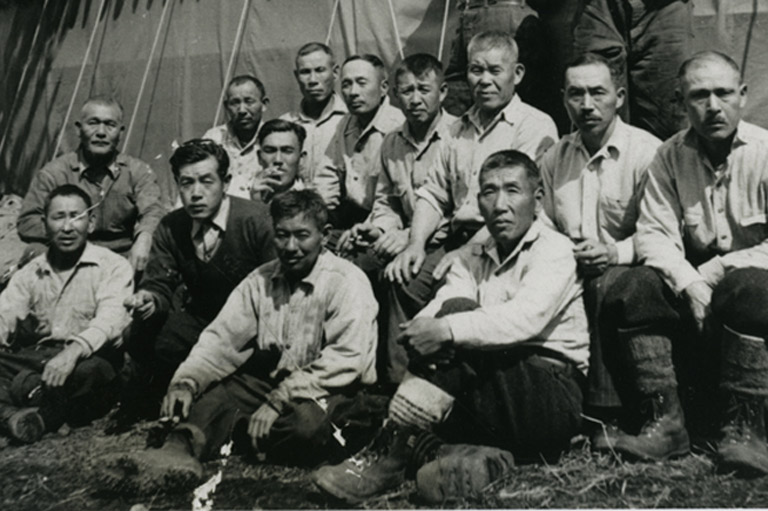

A group of interned Japanese-Canadian men at a road camp on the Yellowhead Pass, March 1942.Library and Archives Canada / PA-118000

A group of interned Japanese-Canadian men at a road camp on the Yellowhead Pass, March 1942.Library and Archives Canada / PA-118000 -

First World War internees at Yoho National Park, British Columbia, clearing a new road along Kicking Horse Canyon.Library and Archives Canada C81374

First World War internees at Yoho National Park, British Columbia, clearing a new road along Kicking Horse Canyon.Library and Archives Canada C81374 -

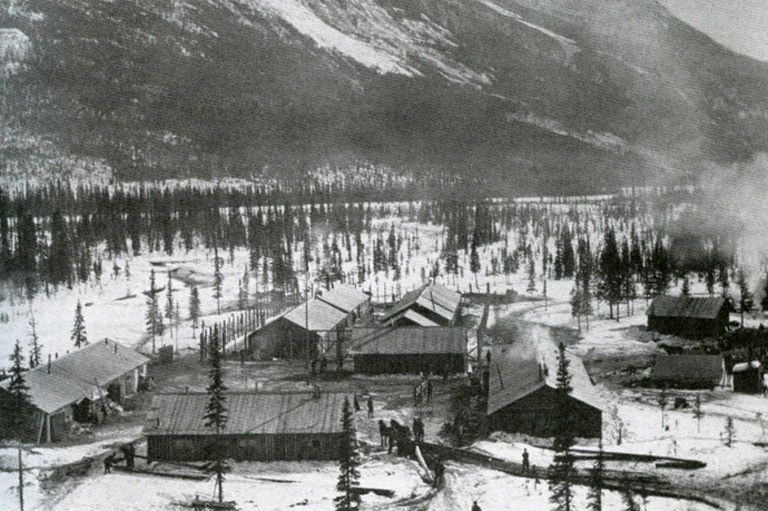

Camp Otter, a First World War internment camp at Yoho National Park, British Columbia.Library and Archives Canada / C81373

Camp Otter, a First World War internment camp at Yoho National Park, British Columbia.Library and Archives Canada / C81373

Clutching a handful of old yellowing photographs, Joe Gabski of Chico, California, arrived at Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba on the morning of September 11, 1991.

Introduced to the park interpreter, he spent the morning telling his story to his incredulous host and then cycled several kilometres along an old road to the site of a former German prisoner of war camp on Whitewater Lake. He had finally returned — keeping the pledge that he had made to himself almost fifty years earlier.

There are other men with similar pasts. Frank Goble of Cardston, Alberta, who served as a cook in the Waterton Lakes, Alberta, relief camps, gladly shows interested park visitors where every one of the camps was located along Chief Mountain Highway while he regales them with stories of the men, the work, and the times.

Abe Dick of Winnipeg performed alternative service work in both Banff and Jasper national parks during the Second World War. He remembers being shuttled between parks along the Banff‐Jasper highway in the back of an open truck in the dead of winter and trying to thaw out during a break at the Columbia Icefield. When he visited the site of one of his former camps near the Maligne Canyon Bridge, he broke down and wept.

A former Japanese resident of British Columbia’s Fraser Valley, however, will never go back to the site of his internment. Ordered from the province in February 1942, he and his father were separated from their family and sent to work on the Jasper section of the Yellowhead Highway. "It has been a very hard experience at that time of my youth," he wrote from Toronto, "and a bitter pill to swallow."

These men, and several thousand others, were sent to Canada’s mountain and prairie national parks between 1915 and 1946 as a part of a general government effort to remove them from Canadian society. They were Canada’s unwanted — enemy aliens, the jobless and the homeless, conscientious objectors, possible subversives, and prisoners of war. They were men who, because of war or economic depression, found themselves viewed with mistrust. The Canadian government wanted to find a place to put them, as well as to keep them busy.

Western Canada’s national parks officials, in turn, welcomed this labour. The parks system was not only undergoing a period of expansion but wanted to take advantage of the coming of the automobile to attract more tourists. To fulfill this role as national playgrounds, parks had to be developed and made more accessible. They needed visitor facilities and improved roads. Joe Gabski and hundreds of others supplied this labour.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

When Canada went to war against Germany and the Austro-Hungarian empire in August 1914, unwelcome foreigners were turned overnight into enemy aliens. Ottawa initially called for public restraint in dealing with these people, but in the end over eight thousand individuals — including women and children — would be held in some dozen stations and camps across the country, including four national parks.

The people made available to the national parks service during the First World War were technically prisoners of war. In reality, the majority of the internees were unemployed or destitute Ukrainians from the Austro‐Hungarian Empire who had been brought to Canada in increasingly larger numbers before the war to work on the railways and other construction projects.

This labour force initially generated little public interest or concern, especially since the men lived on the margins of Canadian society. But with the outbreak of war, the public became alarmed. The government eventually bowed to public pressure and established a national network of internment camps.

The majority of the park internees were stationed at Banff National Park, Alberta, alternating between a summer site near Castle Mountain and winter facilities at the Cave and Basin pool in the townsite, while constructing a new road to Lake Louise. The Jasper internees devoted most of their energies to building a road to Maligne Lake.

Similar work was performed at Mount Revelstoke National Park, British Columbia. With the approach of winter, the men were transferred to Yoho National Park, also in B.C., where they worked on a new highway and a bridge to the Kicking Horse River.

By the end of the first season, parks officials found the work to be satisfactory but complained about the slow pace and the almost constant supervision the men required. One wonders, though, what more could have been accomplished since the internees were using only hand tools. They were also desperately unhappy.

One Banff internee confided to his wife in a letter that they were "hungry as dogs." Some quietly waited for the right moment and tried to escape, even though guards were under orders to shoot. At Yoho, prisoners used a shovel and cutlery from the mess hall to dig their way to freedom. By the time their burrowing activity was discovered, the tunnel reached beyond the stockade wall and was only a few metres from the bush.

Meanwhile, as the war continued, casualties overseas mounted and Canada’s military commitments translated into a serious manpower shortage at home. The government reasoned that the interned aliens might as well be released to fill vacancies in factories and other workplaces. Beginning in April 1916, prisoners gradually began to be discharged.

The Jasper and Yoho camps were closed in the fall of 1916. The Banff operations came to an end the following summer. The Dominion Parks Service regarded the internment camp experience as something of a mixed blessing. Parks officials had expected great things from the internees and were disappointed by what had been achieved. At the same time, Parks Commissioner J.B. Harkin had to admit that the men had tackled jobs that otherwise have been impossible during the war.

There was also a sadly ironic aspect to the park internment operations. Throughout the war, Harkin was forever extolling the virtues of the national parks system and how these special places would provide much‐needed sanctuary when the guns finally fell silent. But in making the wonders of Banff, Jasper, Yoho, and Mount Revelstoke more accessible, the internees had known only exhaustion, suffering, fear, and desolation.

The coming of the Great Depression in the 1930s offered parks officials the chance to operate a new generation of work camps. The swelling ranks of the unemployed reminded parks officials of what the enemy alien camps had accomplished in the mountain parks during the war years. Why not do the same thing with Canada’s growing army of unemployed?

Most of the early relief activities consisted of labour‐intensive general maintenance work in and around park townsites. The Edmonton unemployed, for example, cleared brush to improve grazing conditions at Elk Island National Park, Alberta. Once the availability of a large pool of workers had been assured, however, a number of major road‐building projects were launched.

Several hundred men worked on a highway link between Banff and Jasper, while in British Columbia, others toiled on a road between Golden and Revelstoke, the Big Bend Highway. In the meantime, at Waterton Lakes in southwestern Alberta, major roads were built to Cameron Lake and the international boundary.

At the outset, camp conditions were not ideal. Many men were not properly outfitted for working outdoors in the winter. During a bout of unusually frigid weather at the Jasper end of the Banff‐Jasper highway in November 1932, two highway workers cut a deck of cards to see who would wear a set of underwear and a pair of socks.

These shortcomings aside, the parks department was soon operating an efficient, carefully coordinated relief program. Over the winter of 1931‐32 alone, relief workers provided more than a quarter million days of work.

As for food, men in the camps declared the meals to be wholesome and plentiful. They had to be. The relief workers were expected to do as much as they could by hand; heavy machinery was used only rarely. The bunkhouses in most instances were little more than tarpaper shacks — without insulation!

The bunks were not much better. One worker, who spent four consecutive winters in the park camps from the age of fifteen, suggested that only a horse could enjoy the bedding — the men stuffed their beds with straw delivered by local farmers.

Conscientious objectors — or "conchies" as they were dubbed — would be required to work the equivalent of basic military training in the relative isolation of the mountains and boreal forest.

The most noteworthy feature of the Riding Mountain relief camps in Manitoba was the ambitious recreation program. Because more than one thousand men were housed in a five‐kilometre radius around Clear Lake, park authorities formed inter‐camp soccer and hockey leagues.

The park also equipped an all‐star hockey team and hosted an exhibition match against one of the neighbouring communities every Sunday afternoon before a crowd of a thousand spectators. Future Toronto Maple Leafs goalie Turk Broda got his start guarding the net for the all‐star team.

Beginning in 1934, many parks relief workers finally got the chance to use their trades under the Public Works Construction Act. The result was a number of beautiful peeled‐log and stone structures, many of which have been recognized today as heritage structures.

Indeed, the cumulative result of relief labour was a level of parks development has rarely been matched in national parks history. It is a legacy that stands in sharp contrast to the experience in the troubled Department of National Defence camps during those same years.

When Canada entered the Second World War in 1939, parks officials lost little time in reaching an agreement with the Department of National War Services to establish alternative service camps in national parks. Conscientious objectors, or "conchies," as they were dubbed, would be required to work the equivalent of basic military training in the relative isolation of the mountains and boreal forest, handling projects left over from the closure of the relief camps.

The first alternative service workers reported in June 1941. By summer’s end, camps had been opened at Riding Mountain, Banff, Jasper, Prince Albert, and Kootenay. Temporary camps were also established the following year at Yoho and Glacier in the Rogers Pass area of B.C.

Most of the alternate service workers were young Mennonite men, quietly committed to completing their term of service. Once settled into camp, the men faithfully observed the rules and gave no cause for complaint, let alone a reprimand. Far from being complacent, the truth of the matter was that the men were simply too homesick to cause any trouble.

The men also proved to be hardened labourers. As the war progressed, the men cut brush along highways, sawed firewood, erected new patrol cabins, and rebuilt or relocated several kilometres of telephone line. In the park townsites, they served as local caretakers, servicing the campgrounds, building new kitchen shelters, hauling ice, or grooming golf courses.

They also built a new breakwater at Waskesiu in Prince Albert National Park, in northern Saskatchewan. They also assisted with wildlife management and forest conservation. Teams of men removed some eighteen thousand beetle‐infested trees at Banff, while similar work at Kootenay netted almost one million board feet of lumber.

At Jasper, internees were involved in one of the most bizarre episodes of the war. In the fall of 1942, British inventor Geoffrey Pyke concocted a scheme to fashion a fleet of indestructible warships from "pykrete," a mixture of ice and wood chips.

The idea would likely have been laughed at, but for the fact that Nazi U‐boats were wreaking havoc on Allied shipping. Before construction of the bergships got underway, it was decided to build a small ice prototype in Canada. This work was secretly carried out in early 1943 on secluded Patricia Lake in Jasper by an unsuspecting group of conscientious objectors.

Thanks to the alternative service program, the National Parks Bureau had its own personal army during World War Two. And when Canadians started to visit national parks in unprecedented numbers in the late 1940s, trying to put behind them the dark days of the war, they enjoyed facilities that had been developed, improved, or maintained by men who had chosen peaceful activities over military service.

In the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Canadian government took increasingly severe steps against the Japanese community of British Columbia. The most draconian of these measures was the decision to remove all Japanese residents, including Canadian citizens, living within 160 kilometres of the Pacific coast effective February 24, 1942.

Over thirteen hundred of the evacuated males were immediately sent to work on the Yellowhead Highway between Jasper, Alberta, and Kamloops, British Columbia.

The most easterly section of the new highway was located in Jasper National Park between the townsite and the Alberta‐British Columbia border. There, three temporary work camps — one at Geikie, two at Decoigne — were established in boxcars along the railway siding until the men could build their own camps.

Unlike their attitude to other groups that had worked in the national parks during the previous three decades, Jasper National Park officials wanted nothing to do with the Japanese and tried to limit as much as possible the Japanese presence in the park. They were afraid that they would damage tourism.

The Japanese, for their part, initially co‐operated. But when it became apparent that they might be separated from their families for several months, if not years, they decided to disrupt work — mostly by striking — in an atttempt to force Ottawa to do something about their situation.

Project officials, thoroughly frustrated by the behaviour of the Japanese, believed that the easiest solution was to force the Japanese to work on the road and essentially turn the work camps into concentration facilities. Ottawa, however, decided to reunite the married men with their families in new housing communities in the British Columbia interior and ordered the immediate closure of the park camps.

In the end, the Japanese had forced the Canadian government to recognize a fundamental fact about human behaviour that transcends all races and circumstances — that men should not be forcibly separated from their families.

The last group of workers in a national park setting were German prisoners of war captured in North Africa. In 1943, 440 German prisoners being held at Medicine Hat, Alberta, were sent to a woodcutting camp on Whitewater Lake in the heart of Riding Mountain National Park.

The new Whitewater camp was an impressive facility. Constructed at an estimated cost of $330,000, it featured six large bunkhouses and a number of other structures.

What probably surprised the prisoners most was that there was no enclosed compound or guard towers. Instead, the boundaries of the camp were designated by red blazes on a ring of outlying trees. To help the guards keep track of the Germans, the prisoners wore blue denim work clothes with a red stripe down the outer leg of the trousers and a large red circle — like a target — on the back of the shirt and jacket. This outfit was resented by the prisoners.

The Germans enjoyed a wide range of recreational pursuits. Some of the men had theatrical or musical talents and staged regular performances. Others were fascinated with the forest setting and kidnapped a bear cub for a camp mascot.

A good many also turned their hand to crafts and used the readily available forest to create a number of elaborate models, including ships and bottles. Several of the prisoners also applied their skills to boat — making and hacked out dugout canoes from spruce logs.

Then there were those who liked to wander at night. Using crude compasses made from watches they had ordered from the Eaton’s catalogue, the men would slip away Saturday night after roll call and be back the next morning in time for the first count of the day.

During their clandestine travels, they chanced upon small immigrant communities along the southern and northern boundaries of the park. They became favoured guests at local dances and parties, largely because they carried with them rationed goods.

By the spring of 1945, the Germans had become bored with their woodcutting chores and instituted a series of work stoppages. Ottawa closed the camp and transferred the prisoners to other work projects. The camp structures were torn down, and the site was cleaned up that fall.

But even though the Parks Bureau was determined to eradicate all signs of the camp, it could not erase the fact that for a few brief months during Second World War animosities were set aside and Riding Mountain’s Nazis found a home away from home in the farm communities beyond the park’s boundaries. The dances in those little towns were never quite the same again.

In looking back over the history of Western Canada’s national parks during the two world wars and the Great Depression, it is readily apparent that the story is about more than preservation and recreation. Places like Yoho, Jasper, and Prince Albert owe much to the hundreds of “park prisoners” who gave meaning to the term “national playgrounds.”

They and their work, often performed under duress, need to be more widely recognized and commemorated. In the words of a former park relief worker, the failure to do so would be “a dirty shame.”

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement