Equality for All

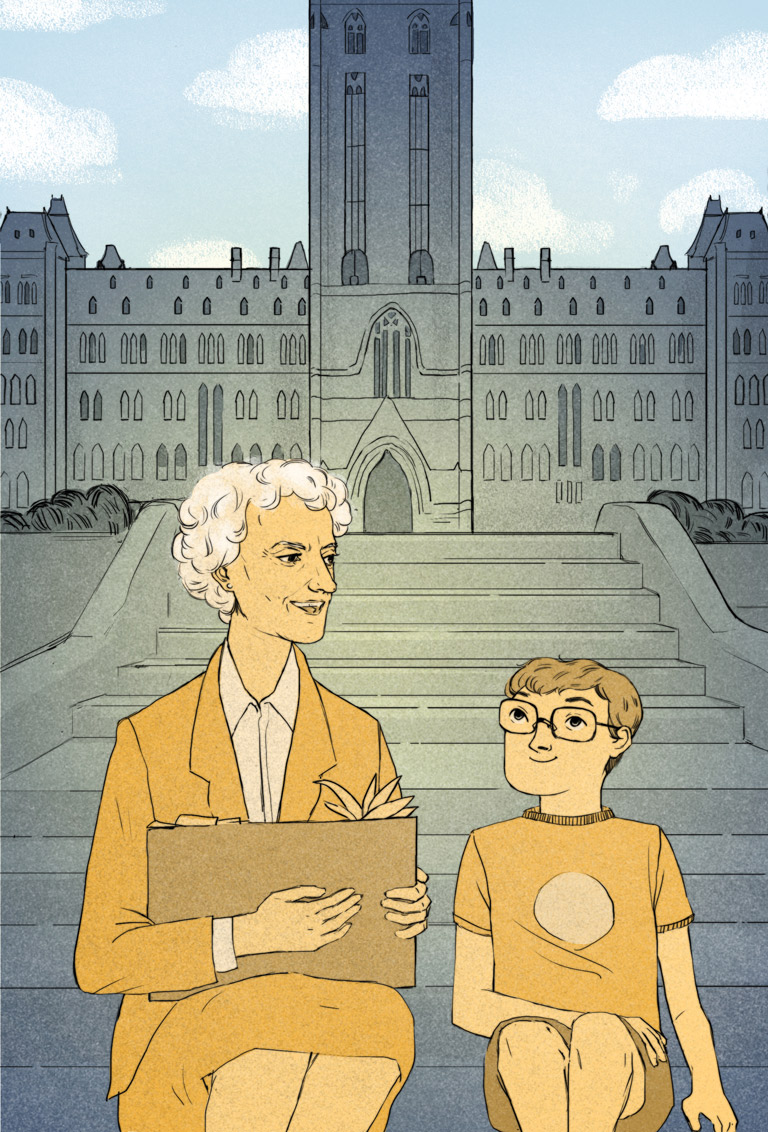

July 1971, Parliament Hill, Ottawa

The summer sun was so hot that Charlie Leduc could feel it, even see it, shimmering up from the pavement in front of the Peace Tower. And still his mother was taking photos!

“I’ll just be a minute or two, mon beau,” his mother called. “The flowers are so pretty!”

Charlie climbed up the steps toward the beautiful old stone buildings. There was a bit more of a breeze at the top. He leaned back, back . . . there! He could see the flag at the top of the tower, but on such a hot, humid day, it was flopping more than flapping.

All of a sudden he lost his balance and fell backward, right into a grey-haired woman in a trim suit. She hadn’t seen him because of the box of books and papers she held out in front of her.

“I’m sorry! Excusez-moi!” Charlie was so used to speaking both languages at home that he apologized in French and English without realizing it.

“De rien. It’s nothing,” said the woman with a friendly grin. “It’s a long way to the top of the Peace Tower, isn’t it? If you’re feeling dizzy, let’s sit down for a moment.”

The elegant woman folded her skirt and sat down on the top step, Charlie beside her. “I’m Charlie Leduc,” he said, holding out his hand. “My mum and I are visiting from Sherbrooke.”

“That’s a lovely part of Quebec,” the woman said with a nod and smile. “I’m Madame Casgrain,” she added as she shook his hand.

“Why do you have that box?”

The woman sighed. “I have to clean everything out of my office today. They say I’m too old for my job. I don’t think 75 is that old, do you?”

Charlie didn’t want to be rude. “Well, it is a bit old,” he said, trying to be kind.

Mme Casgrain burst into laughter. “You’re right, Monsieur Charlie. It is a bit old. But I don’t usually let the rules stop me from doing what needs to be done. I think everyone should be treated equally, don’t you?”

“Of course!” Charlie answered. “But everybody’s pretty much equal nowadays.”

A brief look of sadness on Mme Casgrain’s face was chased by a warm smile. “Things are better now, Charlie, but that’s only because people fought for everyone to have an equal voice. Like you, I am from Quebec. And I have only been able to vote in our province for 31 years.”

That sounded like forever to Charlie, but this time, he stayed quiet. Mme Casgrain seemed to read his mind.

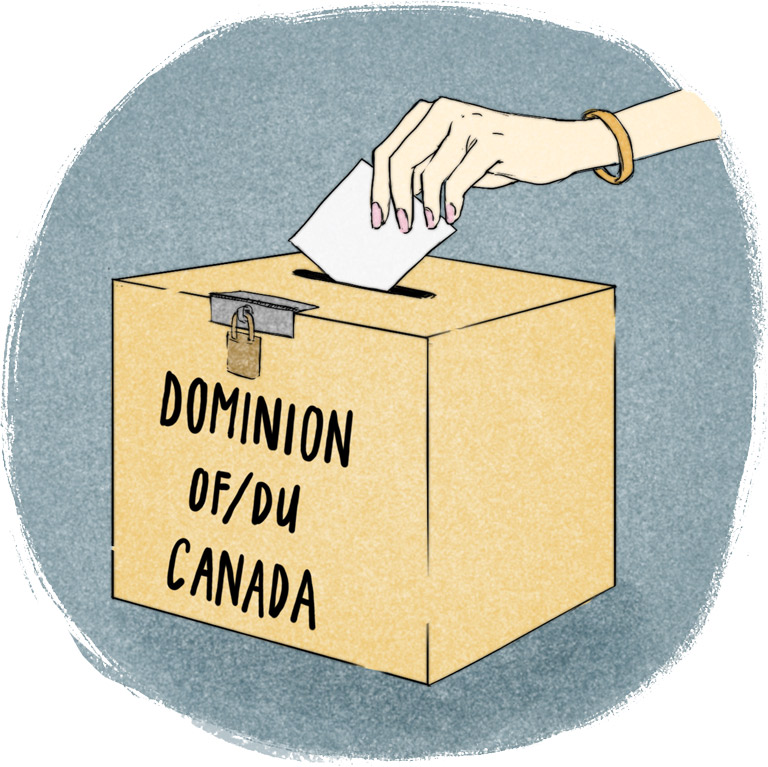

“I know it’s an awfully long time at your age, but 1940 seems like yesterday to me. We started in 1928, and every year, we went to the government to ask for the right to vote. For 12 years, the answer was no.”

“Twelve years? That’s longer than I’ve been alive!” Charlie said. “That’s just silly. Why wouldn’t they let you vote?”

“It seemed silly to us, too,” Mme Casgrain said. “We even sent a petition to the King. Ten thousand people signed it, but still nothing.”

“Don’t you mean the Queen?” asked Charlie.

“It was in 1935, my friend,” she said. “It was still King George back then.”

She started to say more, but turned when she heard someone running up behind them. A worried looking young man burst out, “Madame Casgrain — there you are! I would have helped you carry that box!”

Then he saw Charlie. “Is this kid bothering you?”

Mme Casgrain held out her hand to Charlie and they both stood up. “Quite the opposite. Our conversation has been the nicest part of my day.”

Just then, Charlie’s mother saw what was going on and rushed up the steps. “I’m so sorry! I — ” Her mouth fell open when she saw Charlie’s new friend.

Mum, this is — ” His mother’s face was flushed from the heat and something more. “Madame Casgrain, it’s a great honour to meet you,” she said shyly.

Charlie had never seen his strongminded mother so flustered. “Do you know her?” he asked.

“Everyone knows Mme Casgrain! Without her, women in Quebec might not have any rights at all.” Charlie’s mother turned to the older woman. “I am so grateful for everything you’ve done. And I admire your work for peace and for Indigenous people so much.” She blushed again. “And now I’m babbling!”

She recovered with a smile. “I was so sorry to hear you’ve been forced out of the Senate. Will you retire now?”

Mme Casgrain looked at the young man from her office and winked. “Well, I may no longer be a senator, but I don’t think I’ll be retiring any time soon!”

Thérèse Forget Casgrain

Thérèse Forget Casgrain was born in 1896 and grew up in a rich family in Montreal. Casgrain enjoyed volunteering and being a mother to her four children, but was fiercely interested in politics at a time when women couldn’t vote in Quebec. When her husband, Pierre, a judge and Liberal Member of Parliament, fell sick during an election in 1921, she gave witty, exciting speeches in his place.

Casgrain helped start the Provincial Franchise Committee, later the League for the Rights of Women. It pushed for women’s right to vote in the face of intense opposition from the powerful Roman Catholic church.

She used her radio program Fémina to educate women all over Quebec. When women finally won the vote in 1940, Casgrain didn’t stop. It would take pages to list all the things she did and the honours she won as she worked to improve health care, education and rights for Aboriginal people.

She was the first woman in Canada to head a political party, the Quebec New Democrats, from 1951 to 1957. She started a group called Voice of Women to work for peace, her greatest goal. In 1970, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau made her a senator. She accepted, knowing the rules said she would have to retire when she turned 75 the next year.

Naturally, when she left, she fought for an end to forced retirement while she continued to work for peace and fairness. Thérèse Casgrain died in 1981.

In 1985, Canada Post honoured her with a stamp, and her image appeared on the $50 bill between 2004 and 2012. She jokingly referred to herself as “public busybody number one,” but Thérèse Casgrain made life better for millions of people.

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive features both English and French versions of Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids.

Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids — 3 digital issues per year for as low as $13.99. Tariff-exempt!