The Gift of Gatineau

I am breathless with exertion — and elation — at conquering the steep ascent to Pink Lake. “It’s by no means an easy feat,” my companion Greg Crevier laughs.

We are cycling the paved and hilly roads of Gatineau Park, a nature reserve with a diverse ecosystem and considerable cultural heritage. The park is wedged at the confluence of the Ottawa and Gatineau rivers, just fifteen minutes by car north of Parliament Hill.

More than a hundred years ago, William Lyon Mackenzie King, Canada’s tenth and longest-serving prime minister, also biked the area. It’s easy to see why he fell in love with the region. He purchased a large chunk of it and ensured that the public would enjoy its beauty for generations to come.

Like many other people of his time, King came here to retreat from the grime of the capital city. Although Ottawa is cleaner now, its residents still flock here year-round to enjoy treasured features such as Pink Lake.

We discover that Pink Lake, named after the Irish farming family who settled nearby in 1826, is actually a startling shade of green. However, the beautiful emerald colour is a recent phenomenon caused by eutrophication. Recreational use of the lake caused erosion, which released nutrients that led to excess algae growth.

Efforts are now being made to rehabilitate Pink Lake and preserve its unique characteristics. Formed after the glaciers retreated, it is home to the three-spined stickleback, a saltwater fish that adapted over thousands of years to the fresh water of this lake.

The names of other settlers — Fortune, Meech, Lusk, Mousseau — also live on as place names dotting the park.

Evidence of human habitation goes back five thousand years. Early in the seventeenth century, Algonquin First Nations greeted French explorers Samuel de Champlain and Étienne Brûlé, who lend their names to two of the park’s lookouts. Coureurs de bois lured by the rich trade in beaver pelts soon followed, including the park’s namesake, Nicholas de la Gatineau.

Remounting our bikes, we continue northwest until a green sign directs us into the Mackenzie King Estate.

King fell into a lifelong love affair with Gatineau’s brooding beauty and in 1903 bought a small piece of land on Kingsmere Lake. As he rose in power, becoming prime minister in 1921, he continued buying land, eventually owning an elaborate 230-hectare property, three summer cottages, and a year-round residence.

We follow groups of schoolchildren through white gates and over paving stones laid by King himself. In addition to maintaining hundreds of kilometres of trails in the park, the National Capital Commission offers curriculum-based learning for school groups — in effect, the park does double duty as a giant outdoor classroom.

We wander, taking tea at Moorside cottage, where King entertained guests such as Winston Churchill and Charles Lindbergh. We enjoy the French- and English-style formal gardens designed by King and the collection of ruins he lovingly constructed and tended.

During the last years of his life, he restored an old farmhouse on his estate and it was here that he died in 1950. King’s estate was bequeathed to the Canadian public.

Leaving the estate, we head for the Champlain Lookout atop the Eardley escarpment. Forming a dividing line between the Canadian Shield and the St. Lawrence Lowlands, the escarpment’s unique positioning creates a warm and dry microclimate.

Many visitors share this bird’s-eye view of the Ottawa Valley with us. The park receives more than 1.7 million visits a year, with fall a particularly busy time — the colours displayed by over fifty species of trees draw admirers from far and wide.

The next morning I direct my car along a narrow, winding route on the south side of Meech Lake, named after the Reverend Asa Meech, who arrived in the mid-nineteenth century.

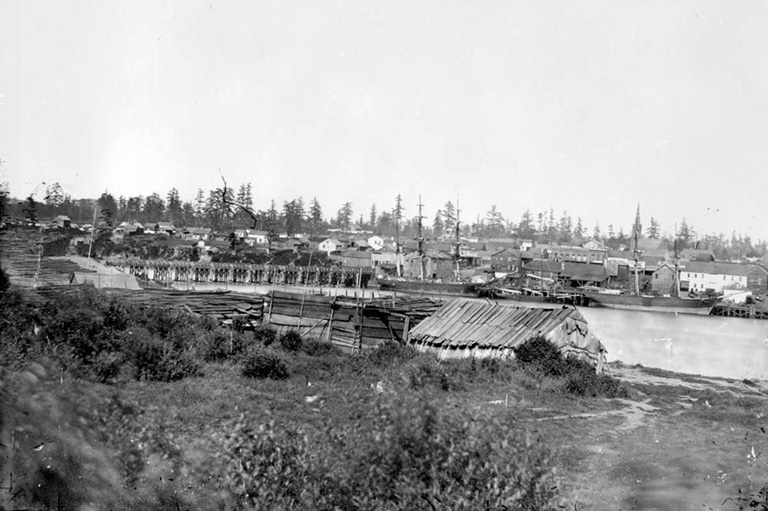

Mining and logging were starting in earnest here then. Towering white pine trees, highly valued for ship masts, were felled and run down the Ottawa and Gatineau rivers, along the same route that iron ore, molybdenite, phosphate, and mica were shipped out after mining.

Logging intensified during the Great Depression, prompting a lobby by preservationists bent on stopping wholesale cutting in the Meech and Kingsmere sectors. King’s government responded with the creation of Gatineau Park in 1938.

I see no remaining signs of clear-cutting as privately owned cottages and homes of all sizes and pricetags dip in and out of view. Across the lake stands the former summer home of Thomas “Carbide” Willson, who made local industrial history by manufacturing calcium carbide.

He was also the first person in Ottawa to own a car. His home was built in 1907 and was eventually converted to a government conference centre. It’s most famously remembered as the 1987 site of constitutional talks leading to the Meech Lake Accord.

Taking highways skirting the park, it takes me thirty minutes to reach Parent Beach on Philippe Lake in the less-busy northwestern area of the park.

A welcoming picnic table allows fuelling-up for the two-hour, five-kilometre walk to Lusk Cave. I carry two flashlights and rain gear in preparation for the naturally formed marble cave. Inside, I can move fairly easily, with no chance of getting lost.

Other cave explorers wear hard hats, and I am careful of my head as I ease through the dripping, murkily lit interior. The lake’s shoreline leads me back to my car. Campers in canoes slide by, and a loon cries eerily before slipping beneath the water’s silky surface.

This is Canada’s capital backyard.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement