Coastal Cruise

It’s the end of June, and flecks of snow dust the craggy coastline of Quebec’s North Shore.

Our plane lands near the rugged little village of Blanc-Sablon, just as the sun is setting in a blaze of oranges and reds.

The brightly lit Nordik Express — a solid freighter and passenger ship — is moored and waiting for us at the village wharf.

Giant cranes heave everything from televisions to refrigerators into theship’s hold, to be disgorged later at one of the isolated coastal villages in the extreme northeastern region of Quebec, more than thirteen hundred kilometres from the province’s capital.

Boarding the ship as economy tourists, we struggle down four flights of narrow, white iron stairs to the bottom deck. Usually there are between forty and seventy sleep-in passengers in various categories of cabins at any one time.

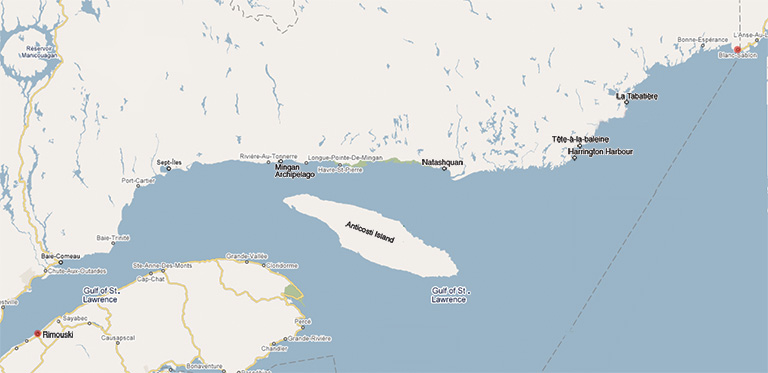

The ship begins its round trip from Rimouski, on the south coast of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Plying its way across to the Lower North Shore, it brings the essentials of life to coastal communities.

No roads join these villages, so the coasters (people who live on the Lower North Shore) go by boat to visit friends up and down the coast. In the winter, they communicate by the “White Highway” — one of the longest snowmobile trails in the world.

The North Shore was once the hunting ground of the Inuit, Montagnais, and Naskapi. Vikings settled here for a brief period in the eleventh century. Five hundred years later, Jacques Cartier — the famed early French explorer — described its barren granite coast as “the land God gave to Cain.”

A hundred years before Cartier, Basque whalers from Spain and France were vying for whaling sites to turn whale blubber intooil for the lamps of Europe.

When word came back from the New World that the waters around the north coast were teeming with cod, fishermen from England, France, Spain, and Portugal replaced the whalers. By the end of the seventeeth century, fishermen and seal hunters were living in North America’s first villages.

Now, about six thousand coasters — a mix of French, English, Irish, and Indigenous peoples — still try to make a living from the dwindling fish stocks. Montrealer Carmen Monetta is typical of the passengers that tour on the Nordik Express.

“The cruise is very popular with Québécois,” she says. “We like the north and the outdoors. You have to reserve a year in advance to get the best cabins.”

As the ship cuts through the waves, we scan the water for whales, icebergs, and seabirds. The weather changes by the minute, from cold drizzle and fog to brilliant periods of sunshine and blue skies.

With each onshore stop, we are treated to a taste of the local history of the region. Brian Evans, the mayor, judge, and social worker of the village of La Tabatière, meets us at the village wharf.

“The native Montagnais were the original inhabitants of La Tabatière” he explains. “The name means sorcerer, as they always consulted a sorcerer before they went into the forest to hunt.”

Once known as the best seal-hunting spot on the coast, the village still looks much the same as it did around 1830, when the painter and naturalist John J. Audubon sailed into its harbour to sketch the water birds.

In his diary, Audubon noted: “Samuel Robertson, the most important landowner, has a vegetable garden, a library, a wine and cheese cellar and receives the newspaper on a regular basis.”

In addition, Robertson maintained the largest seal-hunting operation on the North Shore. Old black iron pots, used to render seal blubber into oil, can still be seen at the remnants of the Robertson factory at Spar Point.

From Tête-à-la-Baleine, Keith Kippen’s speedy launch whisks us to Île Providence. We hike up a rocky path to the lonely, windswept, century-old Chapel of Sainte-Anne. Restored after years of neglect, it’s said to be the only church in the world that has a lobster pot and a lobster net for an altar.

Cloudberry tarts and strong, hot coffee wait for us in the tidy bed and breakfast and interpretation centre in the former priest’s quarters at the back of the church.

We discover that William Kanty, from Jersey, part of Britain’s Channel Islands, bought the archipelago from the bankrupt Labrador Trading Company when the fisheries failed in 1820. Other French families from Jersey, and French Canadians from the South Shore of the St. Lawrence River, soon followed, making it one of only three Francophone communities on the Lower North Shore.

In the early days, the villagers moved to the outer islands to be closer to the cod fishing grounds. This annual summer migration became known as transhumance. Although cod fishing has ended, the villagers still migrate out to their camps when the weather turns warm.

Down the shore, Harrington Harbour — perched on a treeless island nineteen kilometres out to sea — had its brief moment of fame a few years ago. With its pastel-painted houses and wooden streets, it became the setting for the award-winning 2003 movie Seducing Dr. Lewis. “We all wanted to be in the movie,” said Keith Russell, our tour leader, as he guided us through the displays in Howell House, the oldest house on the island and the local interpretation centre.

Suddenly, the horn of the Nordik Express sounds its call for passengers to return. Our time here is over all too soon.

Back on board, the evening menu abounds with gourmet dinners of lobster, salmon, roast beef, blueberry pie, mousses, and tarts. The rugged, rocky scenery is mesmerizing.

Someday, there may be a road between the villages on the Lower North Shore, but right now, time stands still as the coasters try to make a living — just as their ancestors did here centuries ago.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement