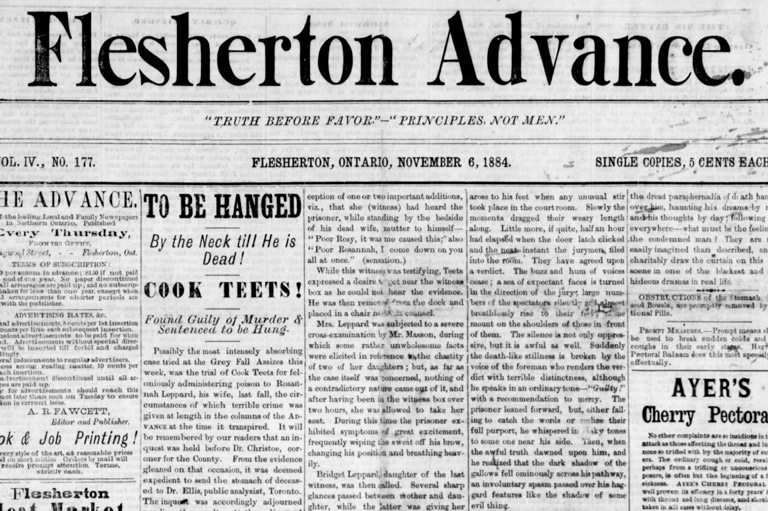

Mystery at Mack Lake

Two guns turned over by me to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police have been returned a year later in accordance with law to become my property as in the interim the owner was not found. These guns were not the property of a man who had lived on Skid Row. Somewhere friends are wondering what happened to him.

When I first saw these guns I was trapping beaver in the spring at Mack Lake, the headwater of Herriot Creek, seventy-five miles as the plane flies and one hundred and fifty as the water flows, south-west of the nearest settlement, the port town of Churchill on Hudson Bay.

Two days of unseasonably hot southern winds during the last week of April turned the deep snow and thick ice to swift-flowing, tumbling water. As I was there without a canoe, the change in weather put an end to my work. The last trap to be picked up was in the Herriot Creek, about a mile below the lake.

I had gone about a quarter of the distance and was pushing my way through a thick growth of small spruce when I came upon an old tent, one end over a pole that rested against a tree, the other on the ground.

I walked over to investigate. Lying close by the tent was a pile of badly rusted traps. In size these were ones, one and a halfs and twos, commonly used for muskrat, mink and marten, fours for taking beaver, and half a dozen or so otter traps, large and strong with heavy teeth projecting from the jaws, a type I had never known to be sold in this part of the country.

The otter traps showed that almost certainly this camp had been made by a white man. No indigenous person would have traps procured in a distant market.

I lifted the canvas. All but the part held above ground by the pole fell to pieces in my fingers. There were exposed to view two guns, rubber hipwaders, two carefully rolled tumplines, a camera, a pump gun for fly repellant, several books, a pile of .270 rifle shells and the brass ends of shotgun shells. Ice held most of these firmly to the ground.

Everything had the appearance of being old, of having been exposed to the elements a long time. I knew the camp must have been set up more than two decades before as the basin of Herriot Creek had been my trapping ground for twenty-one years and during that time positively no one has trapped it except myself and men working with me.

The owner of this tent could read, and the printed word was of such value to him that he brought books on a trip to a spot so remote, that every ounce of weight had to be carefully considered. The camera, of a type to which I was not accustomed, left no doubt in my mind that it had been expensive.

Fine carving on the wooden parts of the twelve-gauge double-barrel shot-gun and unusual working on the slide action of the twenty-two calibre rifle distinguished them from models sold in the North. The missing .270 was the longest in range and most powerful in action of any gun with which I was acquainted.

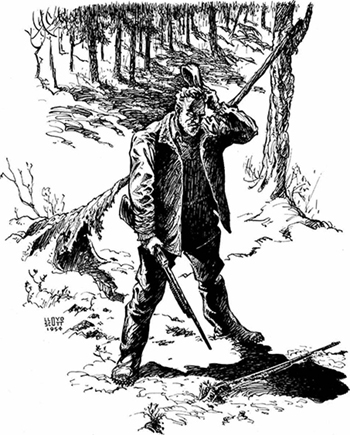

I could not believe this man had left the area alive, as no one would discard such an outfit. From the .270 shells on the ground and no .270 gun it appeared possible that he had left the tent on a hunting trip and never got back. Colour was lent to that supposition by there being no packsack.

Here was a problem for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

Although I knew nothing should be disturbed, in order to delay further rust and decay of the guns I did lift them and place them against a tree.

Immediately on my arrival in Churchill I reported the find to Sergeant James McCardle who at that time was in charge of the local detachment of the Mounted Police. There was no record of a missing person to whom my report might apply.

However, Sergeant McCardle said the owner could be traced by the numbers of the guns, as it had been required in Canada since World War I that all guns be registered. In August, he also said, a plane belonging to the R.C.M.P. would be based in Churchill and I would be required to go at that time to Mack Lake to point out the location of the camp.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Other than the checking of gun registrations, what enquiries were made by the police are unknown to me, as the Force conducts their work with a minimum of publicity. My interest, however, led me to talk to everyone whom I thought might be able to throw light on the mystery.

The Hudson’s Bay store in the town had no record of such a disappearance, as it would have had if a man went into the wilds from any of their posts and failed to return.

The indigenous people of all the surrounding country were living for the summer in shacks and tents around the townsite. My questioning here was among the older men. Did any know of a man disappearing? None had and all declared that previous to my coming they had never heard of a man going up Herriot Creek.

The older residents of the town were consulted. Alexander Oman, born at the Hudson’s Bay post and always living in Churchill, had throughout most of his working years been an employee of the Company. Among his responsibilities had been the keeping track of trappers working out of Churchill.

He assured me that he would have said definitely that no one except me and my associates had ever trapped the headwaters of the Herriot Creek, known to him by its earlier name, Churchill Creek. Questioning of others proved equally fruitless.

During August the police plane arrived, but previous commitments proved so heavy that the Royal Canadian Air Force was requested to make the trip. This they consented to do.

But when at the appointed time I arrived at the airstrip with two of the police constables, the pilot said I could not be included in the party, as no authority had come from Ottawa for him to fly a civilian.

I marked the camp site on a map and gave the constables as explicit directions as I could for locating it.

Towards evening the constables called at my house in town to tell me that my directions, carefully followed, had revealed only that I was trapping in beautiful country.

Shortly before the plane was put down on Mack Lake, the young men had sighted beside an old camping place of mine on the creek a mile below the lake a teepee-like pile of wood put up to dry. For some reason they decided that was the place where the search should be made. In paddling their small canoe down the creek and back to the plane, they had seen no fresh cuttings.

There the matter rested until the following winter when I was again at Mack Lake. So deep a blanket of snow had fallen during the early part of the season that all evidence of the camp’s existence except the ends of the gun barrels was hidden. I took the guns with me and when I returned to town, gave them to the police.

A little over twelve months later the guns were brought back to me. The police had not succeeded in tracing the owner. The guns had never been registered in Canada.

Again my mind is actively concerned with the question of who pitched that tent in the vicinity of far-off, lonely, Mack Lake and what was his fate. The number of guns and their quality and also the type of camera point unmistakably to the owner having been far from poor in this world’s goods.

Both the waders and tumplines indicate that he was a man accustomed to travel off the beaten trail. None but a very experienced outdoors man would have the equipment to patch waders or the skill to do so as efficiently as these had been done.

Did the two tumplines indicate that this camp was set up by two men or was it the headquarters of one man sufficiently experienced in travel by canoe to know a second tumpline often saves time and effort when several loads have to be portaged?

Why was this man at Mack Lake?

The traps, nicely assorted in size for the fur bearers to be had in the vicinity, show his intended occupation was trapping. Yet I feel that to trap was not his basic reason for being there, as at that time much more readily accessible trapping grounds much nearer fur markets were available. Was he a prospector or was he a writer in search of unusual experiences?

Until the opening of the Hudson Bay Railway in 1929, The Pas, five hundred miles south-east, was the nearest settlement — other than a few Hudson’s Bay posts — to Mack Lake.

There were three ways only — as a matter of fact still are — by which Mack Lake could be reached, airplane, dog team and canoe. By airplane was the easiest and most direct. If the flying were done by a bush pilot, surely an arrangement was made for him to return and bring out his passenger. If our man flew himself in, why is there no trace of a plane?

A dog team could have been used during the winter, but there are no signs of dogs having been tethered near the tent, nor of harness, of toboggan, komatik or sled. Certainly he did not have dogs. And if he did come during the winter, why did he provide himself with a gun for fly repellant?

The most difficult way to have reached Mack Lake was by canoe, up Herriot Creek. If our man came this way he must have come down the Churchill River, possibly beginning his trip by water at Flin Flon, the closest railhead to here and not far from the waters of the Churchill.

The usual procedure would have been to continue down the river twenty-five miles and present himself at the Hudson’s Bay post there to get information and supplies. That was not done, an indication that the newcomer wished to keep secret his presence in the area.

The trip from the mouth of the Herriot to the headwater would take a man travelling alone well over a month as there are hundreds of rapids to be climbed, some over a half-mile long. The much patched waders suggest he did come this way.

I know from experience that on the creek a canoe taken by ice will almost certainly be thrown on shore, either whole or in pieces. I have travelled the entire length of the creek many times by dog team and have gone down it once by canoe without seeing a canoe or any part of one along the bank. As well, several winters I have run a trapline for fox around the shore of the lake and have seen no indication of a canoe there.

A lack of any sign of much wood having been cut does establish the fact that the owner was not at the tent for very long after winter set in.

The barren-ground caribou cross Mack Lake during both the spring and fall migration. I have often found that ice over which they had passed would not hold my weight, which is much less than two hundred pounds. A possibility is that after ice had formed, the man was hunting caribou on the lake and broke through.

Murder is a possibility that cannot be overlooked. But if murder it were, regardless of the motive for the crime, the traps, the guns, the tumplines, the waders, everything someone in the area could use, would have been taken.

If someone did away with this man, it may have been a partner who accompanied him for the express purpose. The two tumplines indicate there may have been more than one man in the expedition.

The missing gun would have been the best both for protection and for obtaining meat in getting back to civilization. A man making such a trip would not want to be burdened by the weight of more shells than needed.

During the spring thaw the ice of the lake and of the first few miles of the creek melts rather than breaks. As a consequence there is never a great rush of ice in the vicinity of the camp. The canoe or some part of it should have shown up. Its complete absence may indicate it was used for a get-away.

Everything I found at the tent except the guns is still there. It is possible the books may carry the name of the man who owned them or that the language in which they are printed might furnish a clue. Even at this late date the plates or film in the camera if processed in a good laboratory might show something.

However, most likely if the missing man is identified it will be through the numbers on the guns. I shall be glad to compare these with any submitted to me.

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement