War Crimes

-

Officer Peter MacRitchie of HMCS Prince Robert with liberated Canadian POWs at Shamshuipo Camp, Hong Kong, August 1945.Courtesy of Jack Hawes

Officer Peter MacRitchie of HMCS Prince Robert with liberated Canadian POWs at Shamshuipo Camp, Hong Kong, August 1945.Courtesy of Jack Hawes -

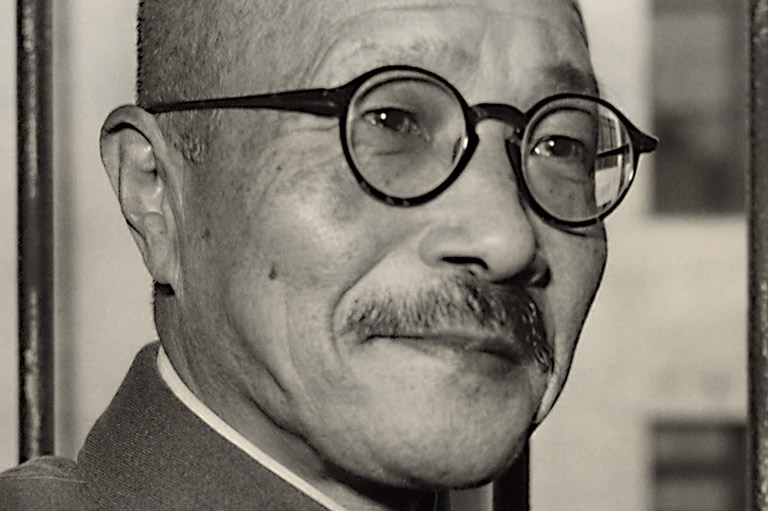

Imperial Army General Hideki Tojo served as Japanese prime minister during most of the Second World War. He was executed in 1948.Canadian Press

Imperial Army General Hideki Tojo served as Japanese prime minister during most of the Second World War. He was executed in 1948.Canadian Press -

Ohashi prison camp in northeastern Japan. The United States Marines rescued Canadian POWs from this camp on September 15,1945.Courtesy of George Macdonell

Ohashi prison camp in northeastern Japan. The United States Marines rescued Canadian POWs from this camp on September 15,1945.Courtesy of George Macdonell -

Members of C Company, Royal Rifles of Canada, and their mascot, Sergeant Gander, in Vancouver in 1941, en route to Hong Kong.Library and Archives Canada / 3241498

Members of C Company, Royal Rifles of Canada, and their mascot, Sergeant Gander, in Vancouver in 1941, en route to Hong Kong.Library and Archives Canada / 3241498 -

Canadian and British POWs at Shamshuipo camp are all smiles after their liberation in August 1945.Courtesy of Jack Hawes

Canadian and British POWs at Shamshuipo camp are all smiles after their liberation in August 1945.Courtesy of Jack Hawes -

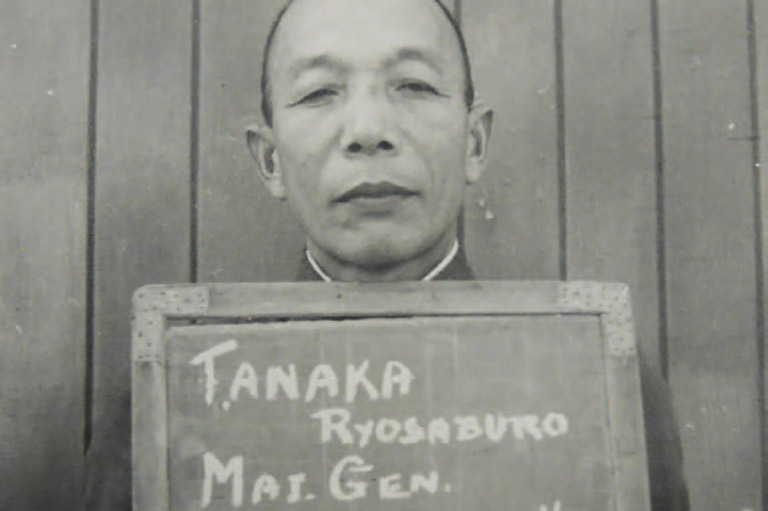

Tanaka Ryosaburo, a major general in the Japanese army, was executed for war crimes following World War II.Courtesy of Nathan M. Greenfield / Library and Archives Canada

Tanaka Ryosaburo, a major general in the Japanese army, was executed for war crimes following World War II.Courtesy of Nathan M. Greenfield / Library and Archives Canada -

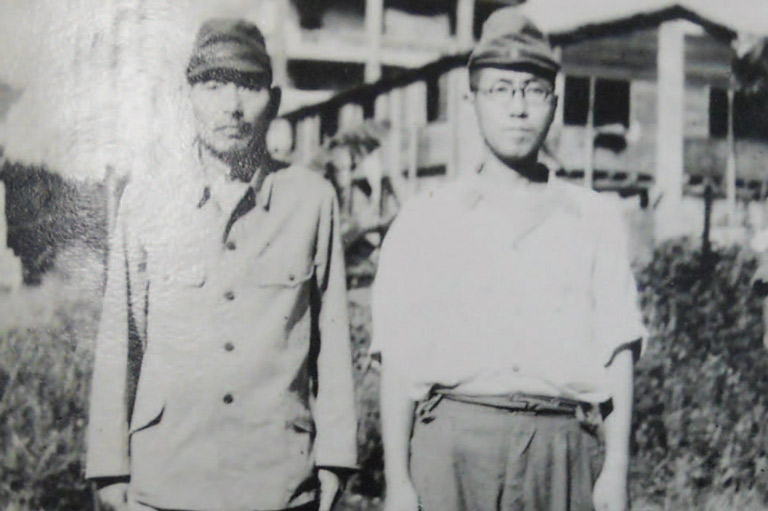

Colonel Esao Tokunaga, left, commander-in-chief of Japan’s Hong Kong POW camps, stands beside his adjutant, Lieutenant Tanaka, following their capture.Courtesy of Nathan M. Greenfield / Library and Archives Canada

Colonel Esao Tokunaga, left, commander-in-chief of Japan’s Hong Kong POW camps, stands beside his adjutant, Lieutenant Tanaka, following their capture.Courtesy of Nathan M. Greenfield / Library and Archives Canada -

Japanese army interpreter Niimori Genichiro, right, was sentenced to fifteen years. Medical officer Saito Shunkichi was sentenced to hang, but his sentence was commuted to twenty years.Courtesy of Nathan M. Greenfield / Library and Archives Canada

Japanese army interpreter Niimori Genichiro, right, was sentenced to fifteen years. Medical officer Saito Shunkichi was sentenced to hang, but his sentence was commuted to twenty years.Courtesy of Nathan M. Greenfield / Library and Archives Canada -

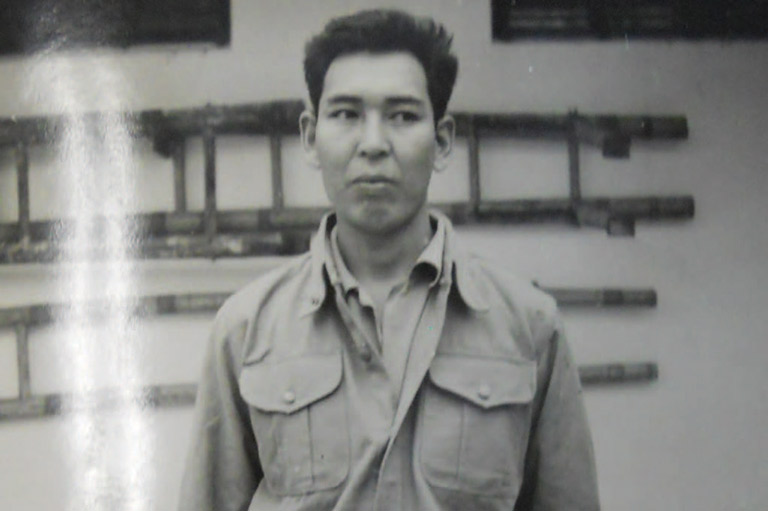

POW John Paul Dallain was held at Niigata, Japan.Historica-Dominion Institute

POW John Paul Dallain was held at Niigata, Japan.Historica-Dominion Institute

In November of 1941, almost two thousand Canadian soldiers arrived in Hong Kong to bolster the tiny British colony’s defence against a possible Japanese invasion.

Most had never been in battle before and were led to believe they would be doing garrison duty. The request for the troops had come from London, and the mission supposedly involved “no military risk,” according to what Major General Harold Crerar told the Canadian cabinet.

Yet political leaders had their doubts. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had originally turned down the idea of defending Hong Kong against what seemed impossible odds, and Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King remained lukewarm to the mission even after his Cabinet approved it.

Unfortunately the prime ministers’ misgivings were borne out.

Six weeks later, 265 members of C-Force were dead and the rest were beginning three and a half years of hellish imprisonment. Over the next four years, another 250 would die from malnutrition, illness, accidents, and execution while working as slave labourers. When the survivors were finally freed, many had been reduced to human skeletons.

Yet, what happened in Hong Kong barely registered with the Canadian public. By World War II’s end, they had become almost inured to suffering. So much had happened since the war broke out in 1939—Dieppe, where even more men were killed, wounded, and taken prisoner than in Hong Kong; Sicily, where 26,000 Canadians landed and 2,400 fell; Juno Beach, where 14,000 stormed ashore and 1,074 were killed or wounded; and, of course, there was the horror of the Nazi death camps.

By the time war crime trials began in Hong Kong and Japan, the human toll of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had begun to become clear, and guilt over the devastating effects of using the atomic bomb—misplaced, in my view—tended to weigh against concentrating on previous horrors. While outrage had greeted the news of the mistreatment of the Canadians immediately after their liberation, the Canadian media almost totally ignored the Japanese war trials between 1946 and 1948.

The Battle of Hong Kong and its aftermath were soon forgotten.

On December 23, 1948, Hideki Tojo, the former prime minister of Japan, was executed for waging “wars in violation of international law.” While count No. 29 referred to the attack on Pearl Harbor, for the 1,477 survivors of C-Force, the count that mattered was No. 31: “Waging aggressive war against the British Commonwealth of Nations.”

The attack on Hong Kong on December 8, 1941, came a few hours after Pearl Harbor. Within moments, Japanese fliers had destroyed the colony’s small air force and murdered many of its civilians.

Hong Kong was defended by a 15,000-man garrison that included the Royal Rifles of Canada, the Winnipeg Grenadiers, two British and two Indian battalions, Royal Navy units, various artillery units, as well as the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps. Garrison commander Major General Christopher Maltby had expected to hold the New Territories of Hong Kong for at least a week. But this was not to be. The better-equipped and battle-hardened Japanese troops pushed his force off the mainland within a few days.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The first Canadians to see action in the field belonged to a company of Winnipeg Grenadiers covering the Royal Scots’ retreat through Kowloon—located on the mainland on the southern tip of the New Territories—on December 12. Two Grenadiers became detached before they could board a ferry to Hong Kong Island. Privates Howard Shatford and John Gray were never seen again and were likely the first Canadian soldiers killed in the Second World War.

The bombardment of Hong Kong was planned by Major General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, who knew Canadians well, having served in Ottawa from 1933-35 as the Japanese defence attaché. But, when it came to his firing plan, his sentimental side, seen in the postcard he wrote to his daughter about snowmen at Rideau Hall, was nowhere to be found; the plan violated the 1907 Hague Convention prohibition against targeting civilians.

During its first few days, the Japanese bombardment destroyed the food distribution system and killed fifty-five soldiers and hundreds of civilians. One explosion in a market on December 16 killed one hundred and fifty civilians. Thousands huddled for safety in air raid shelters.

On December 13, Japanese Colonel Tokuchi Tada embarked on the first of his so-called peace missions. Tada crossed Hong Kong Bay in a flat-bottomed barge and demanded that the colony surrender. Had it not taken place against the backdrop of blasted buildings, the event would not have been out of place in a Wayne and Shuster skit. As he waited for Governor Mark Young’s answer, Tada primped for an American photojournalist and let a British woman hostage who was serving as a human shield give her prized dachshunds to a British soldier for safekeeping. After Young sent his reply—a firm no to surrender—Tada seemed surprised, saying: “It will be a pity if we have to level this beautiful city”

Four days later, Tada tried a second time to obtain a surrender and was again unsuccessful. But his promise of protection for civilians and POWs hid a dark reality: Lieutenant General Sano had already allowed his soldiers three days of rape and rapine in the Wan Chai District of Kowloon, another violation of the Hague Convention’s “laws and usages of war.”

Hidden by mist and thick smoke from burning oil tanks, three Japanese battalions crossed Hong Kong Bay in the early evening of December 18. They made short work of Maltby’s first line of defence, the Rajputs of India, who suffered grievously as shells blasted apart their machine gun pillboxes, which had been built with substandard concrete.

As the forward units of the Royal Rifles engaged fifth columnists on the northwest corner of the island, the Japanese rushed inland towards Mount Butler, Mount Parker, and Jardine’s Lookout. Since Maltby did not think the Japanese would attack over hills and mountains, he failed to occupy these heights. Once seized, these areas opened the way to the Wong Nai Chung Gap, the possession of which allowed the Japanese to split the island’s defenders. Almost two hundred Canadians died trying to dislodge the Japanese from these mountains or defending the gap.

Shortly after midnight, to avoid being cut off, the Rifles fell back toward Stanley on the peninsula on the southeast part of Hong Kong Island. As they did so, a Japanese officer called out to twenty-six Hong Kong Volunteers a short distance away who had not fled their blasted gun emplacement. “No harm will come to you,” promised the officer. “We know you are not regular soldiers.”

Since they had no reason to doubt these words, the volunteers came out with their hands raised in surrender. Within minutes, Lieutenant Aksimus Kishi’s men began plunging their bayonets into the prisoners. The dead and dying were then tossed into pits. Among them were Ts’o Him Chi and Cham Yam Kwong, who played possum after being bayoneted and later crawled to safety. It’s likely that Royal Rifles Sergeant John Cuzner, whose body was found not far away with his wrists bound with barbed wire, was bayoneted at about this time.

General Maltby’s official report speaks of “confused fighting,” an anodyne term for the series of “penny packet” attacks undertaken chiefly by the Canadians over the next few days. In a vain attempt to prevent the Japanese from splitting the island, the Grenadiers climbed Jardine’s Lookout near dawn on December 19 while elements of the Rifles tried to garrison Mount Parker and Mount Butler. Within hours, eighty-four Canadians were dead, including Sergeant-Major John Osborn.

Osborn had taken charge of about sixty-five Grenadiers at Jardine’s Lookout. When hand grenades were thrown at his group, Osborn and his soldiers responded by picking them up and flinging them back at the enemy At one point, a grenade landed that could not be thrown back in time. After shouting a warning, Osborn threw himself over it, thus saving the lives of seven men. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross, the highest award for military valour in the British Commonwealth—and Canada’s first in the Second World War.

Meanwhile, on the lookout, Lieutenant George Birkett, his blood soaking through his uniform, rallied his men around a pillbox filled with wounded soldiers. A shell obliterated them. As Birkett and other men died the horrible—but expected—deaths of combat, Captain Martin Banfill, a Canadian medical officer who commanded the advanced dressing station at the Salesian Mission, located in the hills just south of where the Japanese landed, witnessed other kinds of death—the horrific killings of medical staff and their patients.

Realizing the Japanese were about to storm the building, Banfill yelled for the nurses to run for it. Colonel Ryosaburo Tanaka’s men burst in moments later. The Red Cross flag flying over the building meant nothing to them, nor did the Red Cross identity cards, which the Japanese soldiers stomped on. An interpreter named Honda told Banfill, ‘We have instructions from our commander-in-chief. You all must die.” Two wounded Rajputs in an ambulance were bayoneted. Chinese nurses were raped. Male prisoners, including two Riflemen, were marched away bayoneted, and thrown into a storm ditch.

In one case, a Royal Army medic survived being slashed in the neck by a would-be samurai’s blade. Banfill was told he would be interrogated, then beheaded. But later, after a surreal discussion with Honda about Canadian geography and Christian theology — Honda had been schooled at a Christian mission in Tokyo — the interpreter spared Banfill’s life. The doctor went on to spend the rest of the war as a POW then returned to Canada, where he taught anatomy at McGill University and lived to be ninety-nine.

On December 19, the Japanese pushed further south toward Stanley and westward toward Victoria on the northwest side of the island. Caught behind enemy lines and badly wounded, Grenadier Tom Marsh surrendered and was taken to a twenty-by-ten-metre hut, in which, he wrote, “was gathered all the misery of military defeat.”

The hut was crammed with prisoners. Many were wounded. Some were dead. “The floor literally ran with blood,” Marsh wrote in his memoirs. “There was not enough room in which to lie down, so closely were we packed. Most sat huddled in attitudes of despair with their knees drawn up.”

There was no food, no water, and no medical care. “A few of the prisoners tried to help a comrade or an immediate neighbour but most of us stayed huddled, awaiting we knew not what,” wrote Marsh. “It was now high noon and the sun was hot in the sky. The place was thick with flies pestering the wounded.”

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Japan had not ratified the Geneva Convention before hostilities broke out. However, it had accepted Argentina’s offer to be the “protecting power” for any future British or Canadian POWs. Thus it was seen as having implicitly accepted the convention and its requirement to provide prompt medical treatment, food, and water to prisoners; none of these were provided.

Geneva also called for prisoners to be held in safe places. However, the placement of a field gun near the hut effectively turned the “black hole of Hong Kong” into a giant human shield. Marsh heard the shells exploding nearby as British gunners sought out the Japanese gun. One shell hit the roof. Marsh and some others survived, partly because they were packed so closely together that their comrades’ bodies, including Grenadier lieutenants (and brothers) William and Eric Mitchell, absorbed the force of the blast.

At about the same time these men suffered and died, Royal Rifles Sergeant Major George MacDonnell led his platoon through a water catchment north from Stanley toward Gauge Basin, where they ambushed a large Japanese troop and then barely escaped down the catchment alive. On the morning of December 21, a company of Grenadiers tried to dislodge the Japanese from Mount Nicholson in the middle of the island. It was a futile effort that ended badly Private Keith Lewrie fell when a bullet cut through his brain. Lance Corporal Charles Edgley died in agony after two bullets pierced his stomach. They were among nineteen Grenadiers who perished on the mountain’s slopes.

Later that day the Royal Rifles were pushed off the hills north of Stanley at a cost of seven more Canadians. A shell turned Corporal Joseph “Little Joe” Fitzpatrick into “pink mist.” By late on December 21, the Japanese had isolated the garrison at Stanley in the southeast and reached the bays south of the middle of the island. The next day Japanese pushed west to mop up the last resistance in the Wong Nei Chong Gap, and then drove the Rifles off Stanley Mound and Sugar Loaf Hill.

Perched above Deep Water Bay were two mansions in which a couple dozen British and Canadian soldiers had taken shelter. At dawn on December 23, the Japanese ignored the white flag fluttering over Overbays House and attacked.

The first soldier burst through the door spraying fire with his machine gun. An interpreter who had arranged for the surrender was soon pinioned to the door with bayonets. A Japanese soldier climbed the stairs, kicked in a door, and fired his machine gun, while those behind him tossed in hand grenades.

A few unwounded men threw the slow-timed grenades out the window, but one exploded, blasting shrapnel into Royal Canadian Ordnance Corpsman Leslie Canivet’s jaw. The Japanese fled the house, returning a few minutes later to pour gasoline around it and set it alight. Canivet and a few others managed to jump out a window, the screams of their dying comrades trailing behind them.

The deaths at Eucliff Castle were no less horrific. British and Canadian soldiers were beaten before being lined up on the top of a grassy bank and shot. Twenty-eight Allied soldiers died at the castle.

Outgunned and outnumbered, Governor Sir Mark Young surrendered on Christmas Day but not before many more had died. Twenty-five Royal Rifles died and seventy-five were wounded in a hopeless attack north of Stanley ordered by British Brigadier Cedric Wallis. Wallis ordered the assault even though he knew surrender was imminent, and he then flirted with a Strangelovian fantasy that included blowing up Stanley Fort.

Advertisement

Just to the north, St. Stephen’s College Hospital was attacked in what was among the most ghastly and inhumane incidents of the battle. The Japanese murdered wounded soldiers in their beds; Rifleman Sidney Skeleton survived only because despite his anaesthetic-befogged mind he found the wherewithal to roll under his bed and play dead. Colonel Tanaka’s soldiers gang-raped nurses on mattresses thrown upon the corpses of the slaughtered patients.The nurses were then killed and their bodies mutilated. All this was done by soldiers whose pocket-sized field manual, the Senjinkun, ordered them to “show kindness to those who surrender.”

A month after Hong Kong fell, Tokyo issued a statement saying that in dealing with Allied POWs it would abide by the Geneva Convention. Less than two weeks later, after learning that dysentery had broken out in the POW camps in Hong Kong, London signalled Tokyo that failure to allow the Red Cross or Argentina to verify the condition of the POWs would be taken as proof that they were being mistreated. Tokyo ignored the message.

At the end of February, a cable from Vincent Massey, Canada’s High Commissioner in London, spoke of “studied barbarism” in the running of the camps. By then, most men had lost more than twenty pounds and many were showing the first signs of avitaminosis that would soon lead to the excruciating pain of “electric feet,” the swelling of wet beriberi and temporary blindness. Dysentery was widespread—sufferers lay in their own waste on concrete floors.

On March 10, 1942, Sir Anthony Eden told the British House of Commons, “The Japanese claim that their forces are animated by a lofty code of chivalry, bushido, is a nauseating hypocrisy” When diphtheria broke out later in the year at Shamshuipo POW camp in Hong Kong, the camps’ medical officer, Dr. Saito Shunkichi, preferred slapping Allied medical officers—as punishment for allowing their patients to die—to releasing life-saving serum looted from Allied stores. About a hundred Canadians lost their lives as a result.

After the war, Prime Minister MacKenzie King’s government in Ottawa was lukewarm to the idea of war crimes trials, citing the problem of ex post facto law—laws created after the fact. In the end, however, prosecutors were appointed to serve in Hong Kong and in Japan. Canada’s chief prosecutor in Hong Kong, Major George Puddicombe, was assiduous in collecting evidence against Japanese officers, soldiers, and camp guards.

The National Archives contains files that list dozens of separate beatings in Hong Kong and Japan. But many incidents—such as that involving Canadian Signalman Georges “Blacky” Verreault, who was forced to do push-ups over a shovel of burning coals—did not make it into the official record.

The massacres at the Salesian Mission and at St. Stephen’s Hospital were central in convicting both Lieutenant General Ito Takeo and Major General Tanaka. Puddicombe, who had been a Crown attorney in Vancouver, convinced the military tribunal that Takeo was also responsible for the killing of British troops taken prisoner near the Repulse Bay Hotel. Takeo received a twelve-year sentence.

Tanaka’s defence argued that he could not have been responsible for war crimes because (a) he had told his men to treat POWs correctly and (b) he had lectured them on their Geneva responsibilities before they went into battle in China. The court, however, disregarded Tanaka’s courteous manner and his statement that “no civilians or soldiers were executed at the Salesian Mission.” Banfill’s testimony was central to convicting Tanaka, who received a twenty-year sentence.

Medical officer Saito Shunkichi and Colonel Esao Tokunaga, commandant of the Shamshuipo POW camp, were convicted of failing to provide medicine and sufficient food. Shunkichi’s death sentence was commuted to twenty years, while Tokunaga was sentenced to death.

Tokunaga faced an additional charge of compelling POWs to sign a pledge saying they would not escape, which contravened the Geneva Convention’s recognition that POWs have a duty to try to escape.

On August 19,1942, Grenadier Sergeant John Payne led the one escape by Canadians. A few days earlier, the twenty-three-year-old wrote a letter to his mother saying playfully that, “just in case I shouldn’t make it, you must remember that according to our beliefs I have departed for a much nicer place, although it will grieve me to exchange the guitar for a harp.”

Payne and three other Grenadiers clambered over the roof of Shamshuipo’s hospital and found their way to a boat, which capsized. After being fished out of the water, they were turned over to the Kempetai, the Japanese secret police, who beat them with baseball bats before tying their hands with barbed wire and killing them.

Puddicombe’s failure to find these Grenadiers’ remains appears to have haunted him. He refers to the hill on which he believed them to have been buried, and on which he erected a small marker memorializing them, as “that terrible Golgotha.”

Over the course of a year beginning in early 1942, more than 1,100 Canadian POWs were sent to Japan to be slave labourers. They were crammed into ships’ holds so tightly that they could not all sit down at once. They were given little food and water and by the end of their journeys were covered in feces and vomit. But no war crimes charges were laid against those who organized and ran these hell ships.

Similarly, no one was charged for the hundreds of men who were forced to labour at back-breaking work—carrying away baskets of dirt at the airport in Hong Kong, unloading grain, or toiling in coal mines, shipyards, and factories. On many days they had only a handful of rice or watery soup to sustain them. Some men ate grasshoppers.

Ottawa had ordered that charges only be laid in cases of death or permanent injury. Thus, Lieutenant Kosaku Hazama, the commandant of Oeyema POW camp, where prisoners worked at a nickel mine, was found guilty of allowing beatings and the theft of Red Cross parcels. The small amount of food the parcels contained often made the difference between blindness and sight — or life and death. The unassuming-looking former economics professor was sentenced to fifteen years of hard labour.

At another camp, Niigata, the work was excruciating. Rifleman Jean-Paul Dallain worked ten hours a day swinging a sledgehammer just steps away from a white hot furnace — he witnessed another POW doing similarly hard work lay down and die. Another Rifleman, Ken Cambon, pushed huge hoppers filled with coal up a railway incline. In his spare time, the future Vancouver physician risked a severe beating for hiding and furtively reading A Pocket Book of Verse.

A number of guards at Niigata were tried for mistreating or causing the deaths of prisoners. Guard Katsayaru Sato was sentenced to forty years for the torture and murder of Rifleman James Mortimore, who, after being accused of stealing a tin of bully beef, was tied to a post barefoot in the snow. He was kept there for ten days, during which time he was beaten repeatedly. Mortimore’s feet and legs turned black and he died an agonizing death from gangrene in April 1944.

The defence team for guard Kanemeso Uchida argued that the many mistreatments he issued with his fist, sword, or stick “were only the result of age old Japanese customs” and common in the Imperial Japanese Army. While true, war crimes judges disregarded this point and sentenced Uchida to death. In late 1946, two other guards, Hyoichi Okuda and Takeo Takahashi, were sentenced to thirty-three and fifteen years respectively.

Few Canadians were aware of the Japanese war crime trials, in part because much of the attention of the public was focused on what was happening in Europe after the war ended. For instance, in December 1945, Canadians were transfixed by the trial of S.S. Brigadefuhrer Kurt Meyer for the massacre of forty-one Canadians in the days following D-Day.

The Meyer trial was part of the unmasking of the horror of the Third Reich. And Meyer’s trial by a Canadian court, made it “our story,” as it were. The trials in Hong Kong and Japan, by contrast, took place under British and American auspices. Furthermore, the Pacific War was perceived as an American show.

What Count Galeazzo Ciano famously observed of politicians and generals — “Victory has a thousand fathers, defeat is an orphan” — applies also to nations. C-Force suffered a one-hundred-percent casualty rate. After the war, Canadians were simply not interested in the details of the defeat of Hong Kong and of the long years that followed.

Yet, as of this writing, these details remain the lived experience of some thirty Canadians.

A chaplain under fire

On December 22, 1942, at the Wong Nei Chong Gap, Canadian Chaplain Uriah Laite was in a makeshift pillbox filled with about thirty wounded soldiers when the Japanese approached. The Grenadiers had managed to hold out against attackers for three days but had run out of food, water, and ammunition. With no further defence possible, a wounded officer stepped out of the shelter to surrender.

In accordance with the Geneva Convention, just before the surrender, Laite, who had tirelessly tended to the wounded, threw all of the weapons out of the pillbox’s window.

“Immediately after our surrender I was led out and searched,” Laite wrote in his diary. “Through their interpreter they learned that I was a chaplain—or minister, as he called me. I showed them my Bible and field dressings and told them that my duties were with the wounded. I had made a complete list of our casualties in my notebook. They took it and my pencil. I asked for water for my wounded, which they readily gave me, but watched closely as I gave each chap an allowance…

“On my return from questioning I realized that the walking might have a chance, and said, ‘Boys, if any of you can walk, for God’s sake do so.’” Three Canadians and two British soldiers too badly wounded to walk were left behind in the shelter and never seen again. Laite himself spent the rest of the war as a POW and returned to Canada after the war. He was awarded the Military Cross for his actions.

Hong Kong refugee family flourished in Canada

Among the families caught in the Battle of Hong Kong was that of Australian-born William Poy, an ethnic Chinese businessman and trade representative for the Canadian government. Poy was also a lance corporal with the Hong Kong Volunteers and received the Military Medal for his bravery during the battle. For a time he sheltered his wife, Ethel, and his two children — six-year-old Neville and two-year-old Adrienne — in the motorcycle dispatch rider’s basement.

After six months, the family gained safe passage to Canada as refugees. Poy’s son Neville went on to become a plastic surgeon whose research helped trauma victims and earned him the honour of being made an officer of the Order of Canada. He is also the Honorary Lieutenant-Colonel of the Queen’s York Rangers.

Poy’s daughter Adrienne, meanwhile, grew up to become Adrienne Clarkson, Canada’s twenty-sixth Governor General. During her installation speech in 1999, Clarkson referred to her family’s flight to safety: “To have been brought up by courageous and loving parents was a gift that made up for all we had lost.”

The notorious Kamloops Kid

In April 1947, Kanao Inouye stood before a judge and called out, “My mind and body belong to the Japanese emperor!” The words were uttered not by a Japanese war criminal but by a Canadian. Inouye was born and raised in Kamloops, British Columbia, which explains one sobriquet: the “Kamloops Kid”; the other, “Slap Happy,” came from the fact that he was a sadistic torturer.

When the war broke out, Inouye had been studying in Japan. In 1942 he was drafted into the Japanese army. Because of his perfect English, he was sent to Shamshuipo POW camp in Hong Kong, where he became known for his cruelty.

Inouye tortured Grenadier Jim Murray by tying him to a pole, taping his mouth shut, and shoving burning cigarettes into his nose. On December 21, 1942, he slapped and kicked Captain J.A. Norris and Major F. T. Atkinson when they did not appear quickly enough for a roll call. He told his former countrymen that all Canadians would soon be slaves and “Your wives and sisters will be raped by our soldiers and anyone resisting will be shot.”

The military tribunal discounted his claim that he was only an interpreter at the POW camp, and later for the secret police, and found him guilty of war crimes.

However, he appealed, arguing that the International War Crimes court could not try him because he was a British subject. Telegrams shot back and forth between Hong Kong and Ottawa concerning Inouye’s citizenship. If Inouye’s lawyers thought establishing that he was a Canadian would save his life, they were mistaken. He was tried again, this time for treason. He was found guilty and hanged. Inouye’s last word was “banzai!”

A continuing battle

In the years immediately after the war, the surviving Hong Kong veterans tended to keep their stories to themselves. By the mid-1960s, as their terrible treatment as POWs began manifesting itself in a much higher than expected death rate among the middle-aged former prisoners, the Hong Kong Veterans Association of Canada was formed to lobby for better pensions, benefits, and compensation.

The effort to improve the lives of veterans — many still suffering the after-effects of malnutrition and tropical diseases — was a long, uphill fight. In 1971, the government of Canada granted a basic fifty-percent disability pension for “undetermined disabilities.” It took almost thirty years of fighting the bureaucracy to get the disability pension raised to one hundred percent. In 1998, three hundred and fifty vets and four hundred widows received compensation from the government of Canada. The veterans still seek an apology from the government of Japan.

In 2011, about thirty Canadian veterans of Hong Kong remain alive. But the sons and daughters of the veterans have taken up the task of preserving their legacy, forming the Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association, which continues the work of educating Canadians on the role of Canada’s soldiers in the Battle of Hong Kong.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.