Transforming Religious Heritage: Montreal

Montreal has been called “the city of 100 bell towers.” Its high population density, combined with the fact that it is made up of a merging of many parishes, explains the city’s great number of religious buildings. Certain parts of its religious built heritage have remained unchanged, others have been transformed or destroyed, and yet others are in imminent danger.

Several of the conversions are remarkable, both in their approach and their outcome, while others are less successful. As promised in the first article in this series, in which we outlined the criteria for a successful transformation, we will now take a look at a few remarkable examples in Montreal.

Success stories...

Notre-Dame-du-Perpétuel-Secours Church

This is a near-perfect transformation: an old church preserved as an arts centre that promotes social inclusion and cultural growth—all of which was endorsed through a public consultation process. The Théâtre Paradoxe, located at 5959 Monk Boulevard, was thus born!

The building, with an exterior dating to the 1910s and an interior from 1930–1940, is an eloquent example of architectural heritage displaying two opposing styles of craftsmanship. In 2012, after more than a decade of consideration on the part of the diocese, the Paradoxe Group acquired the building and began the conversion. The stained-glass windows by Guido Nincheri and the solid wood doors were preserved, the wood from the confessionals was reused to make a bar, and the nave was refurbished as a multi-functional space, mainly for cultural use. The building was also outfitted with the equipment required to bring it up to standards, without any major modification to its structure.

Perpetuation of the structure, reuse of distinctive elements, use for social and cultural purposes, preservation of clear religious symbols expressing its past use: this transformation should certainly be regarded as a source of inspiration!

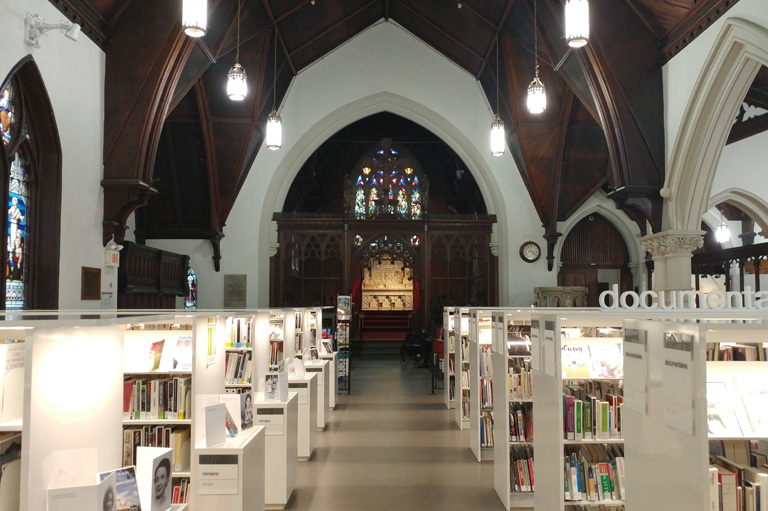

Wesley United Church

Wesley United Church, built in 1926–1927 in the neo-Romanesque style, is another example of a conversion that both respects the past and shows a strong vision for the future. Located on Notre-Dame-de-Grâce Avenue, this place of worship was never sold, unlike most other converted churches. Facing financial challenges, Wesley’s congregation came up with a strategy to convert the building and bring it up to standards, while ensuring its sustainability and the continuity of its educational role (the congregation ran a Sunday school in the church).

In August 2004, after a redesign of the large spaces (including the nave), updates to the facilities, and great efforts to preserve the religious elements, two daycare centres—one of which is an early childhood care centre—took possession of the premises. The result is a space that has been kept alive with a role closely linked to its original vocation, all of which was achieved in an economically responsible project. Of note: no direct government funding was required. .

...and examples to avoid following

Beer-Sheba Church

When a religious building is transformed into a luxury residence, people are generally of two opinions. The first prefers destruction over the desecration of a sacred site. The second champions sustainability, no matter what the new function may be. But is not conservation without any effort to commemorate former use simply destruction in disguise? The question remains in the case of Beer-Sheba Church.

Beer-Sheba Church was located on 4th Avenue in the Old Rosemont neighbourhood. Today, one would hardly be able to guess that the building once was a Protestant place of worship. Built in 1923, this once key building for Montreal’s United Church in the 20th century was declared a “building of architectural and heritage interest” by the city of Montreal in 2004, which should have ensured its integrity according to the Master Plan. Yet, two years later, it was turned into luxury condominiums. And the update to the Master Plan, in 2016, no longer shows any trace of the church…

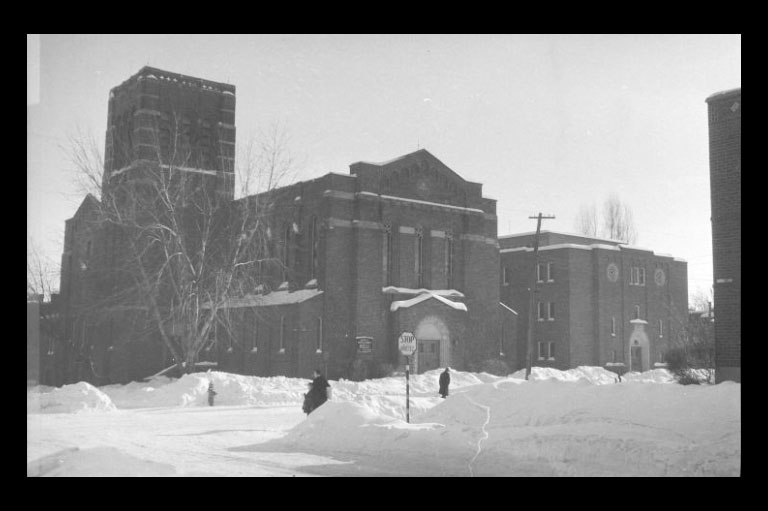

Saint-Columba Church and its community centre

Saint-Columba Church and its community centre have not (yet) been destroyed, nor have they been transformed. However, certain similarities to the Beer-Sheba situation suggest that another transformation—or even destruction—may be in the cards.

The sale of the property to a real estate developer in 2013 pointed to a transformation or destruction. Yet, in 2014, the city of Montreal stated that the church, built in 1920, and its centre were of certain heritage interest. The site therefore seemed safe.

However, in 2016, the city of Montreal accepted Project PP-87, involving the withdrawal of heritage recognition and the destruction of the building. Citizens attempted to come to the rescue by invoking the right to a referendum—a right abolished by Bills 121 and 122 in 2017. Finally, the church and its centre were not protected in the updated version of the city’s Master Plan.

In brief, the church is abandoned today. It has no protection, and citizens are restricted to passive opposition. There is little likelihood that a new project to destroy the building could be stopped, except with the unlikely intervention of elected officials.