The Blast Doors Are Open

In 1959, a deep underground fallout shelter was commissioned by Prime Minister John Diefenbaker as part of his government’s reaction to rising threats of nuclear conflict between the West and the Soviet Union. Nicknamed the “Diefenbunker” by opposition politicians, the massive four-level, 9,300-square-metre underground fortification was capable of withstanding a five-megaton blast from 1.8 kilometres away.

Today, as old apprehensions have been rekindled by the USSR’s primary successor nation, Russia, and its war with neighbouring Ukraine, the site allows visitors to travel back in time to the 1960s and the fear of nuclear attack.

From the national capital, a short drive west through the Ottawa Valley takes you to what is now officially named the Diefenbunker: Canada’s Cold War Museum. After parking, walk over to the white building with the big Diefenbunker sign and enter the blast tunnel.

Partway down the tunnel, a right turn leads to the reception centre, where admission ranges from $11 for youth to $17.50 for adults. Here you can book a guided tour, if you haven’t already done that online, or you can begin a self-guided foray into the Cold War experience. A four-level scale model of the complex shows how everything fits together.

Top-secret heavy-duty construction began in 1959 under a cow pasture near the village of Carp, thirty kilometres west of downtown Ottawa. Local farmers had a good idea what was going on, although the cows didn’t care.

The facility’s purpose was to safely house key government and military officials, but not their families, for up to a month in the event of a nuclear attack — so they could direct governance and the rebuilding of whatever remained outside their safety pod. Ordinary Canadians, as always, were on their own, unless they wished to build a bomb shelter in their basement or backyard.

Military restrictions prohibited the prime minister from being accompanied by his wife, Olive, and for that reason John Diefenbaker was rumoured to have refused ever to use the facility. In fact, he never visited his namesake bunker. The only prime minister to do so was Pierre Trudeau — and he was so underwhelmed that he reduced its funding.

Building the bunker took eighteen months and required about twenty-five thousand cubic metres of concrete plus more than 4,500 tonnes of steel. It was the first recorded use of the time-saving critical path construction method in Canada. The bunker became operational in 1961, and the site remained active as military base CFS Carp until it was decommissioned in 1994.

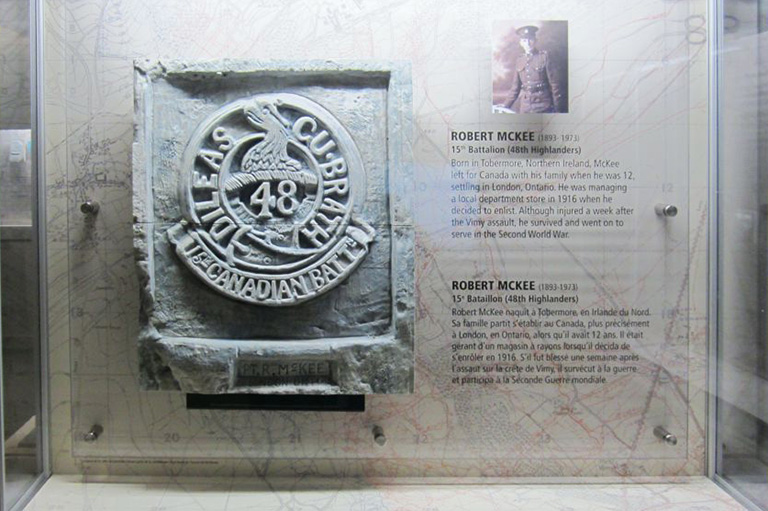

The Diefenbunker was the largest and most important of a series of similar, strategically located Emergency Government Headquarters built across Canada, most of them in rural areas near cities. The others were closed by the 1990s, although items recovered from some of them have been used in the Diefenbunker museum.

There, visitors can walk through underground facilities that were designed to protect 535 people for thirty days, with air filters and positive air pressure to prevent radiation infiltration. Storage was available for food, fuel, fresh water, and medical supplies — all the presumed necessities for a subterranean city in lockdown. Cold War life in the Diefenbunker would have been restrictive. The spaces visitors see today are small, and there would have been no outside light, unless you were sent up top to check things out after a nuclear attack. Then you would have had to pass through a decontamination chamber to get back in.

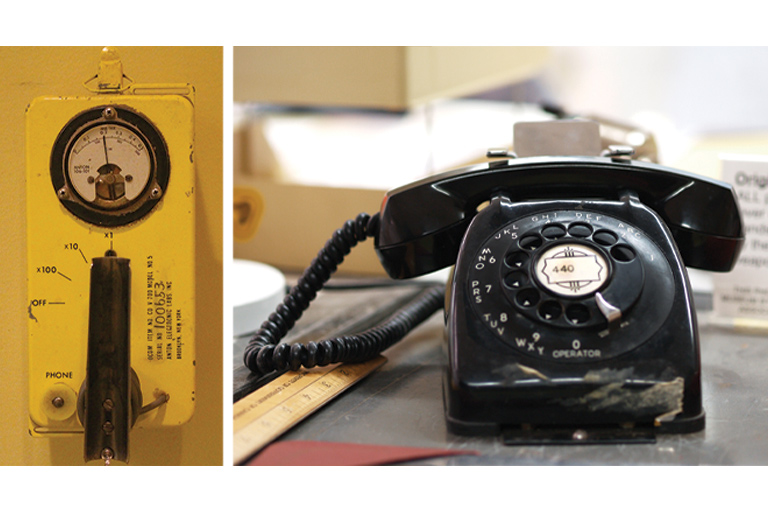

Twenty-first-century techies will enjoy the special cryptographic areas with telecommunications equipment like the Signal Transmission and Receiving Distribution first-generation computer system, magnetic tape machines, mainframes, individual operator screen terminals, old hard disk and RAM cards, plus Geiger counters and rotary phones. All were state-of-the-art then but are now amusing artifacts.

Walk into the cavernous and nowempty Bank of Canada vault that was intended to store the country’s gold reserves. It was called the “Special Storage Area” by workers during construction. Opening the vault required co-operation. Two people opened a small door to equalize internal and exterior pressure, then four people with different combinations to four locks opened the main door.

Tours include the machinery room, washrooms, office workspaces, small private living quarters for the prime minister and Governor General, space-saving “hot bunking” sleeping cots for staff required to work shifts, an operating room, a dental clinic, a cafeteria, a “Situation Centre,” offices for External Affairs and Public Works, plus the CBC Emergency Broadcasting Studio. But would there be anyone out there listening?

While government leaders did not find the facility appealing, the movie industry did. Parts of the 2002 film The Sum of All Fears, starring American actor Morgan Freeman, were shot in the Diefenbunker, as well as scenes from the 2017 movie Zygote, featuring Dakota Fanning. The bunker’s cafeteria has been the location for many receptions and special events.

Then there is the escape-room experience called Escape the Diefenbunker. It is considered the world’s biggest such game room, because participants have sixty minutes to investigate one entire bunker level — more than two thousand square metres — for clues and codes that will help them get out.

The Diefenbunker was designated a National Historic Site when CFS Carp was decommissioned. The site remained empty until the founding of the museum in 1997. It opened to the public the following year, and in 2022 federal funding of $600,000 was granted to upgrade facilities and to improve exhibits.

Tours exit through the museum gift shop that offers Cold War and 1960s memorabilia, including spy gadgets, postcards, books, vintage games, mugs, retro candy, and bunker apparel and accessories. There are even Nuclear Blast hot sauce and Bombs Away shot glasses.

IF YOU GO

GETTING THERE: The Diefenbunker makes a great day trip from downtown Ottawa. Travel thirtyeight kilometres west on highway 417 to Carp Road; take exit 144, turning right past the private Carp Airport and continue through the village of Carp to 3929 Carp Road, on the left. Parking is free. Public transit to Carp is available only on Wednesdays.

EAT AND DRINK: After visiting the bunker, grab a bite at eateries like Alice’s Village Café, the Swan at Carp pub, or Pong’s Poutine takeout. Sample a fermented beverage at Ridge Rock Brewing Co. or visit KIN Vineyards family estate winery, Ontario's most northerly Chardonnay and Pinot Noir vineyard.

EXPLORE: The annual September Carp Agricultural Fair dates from 1863 and calls itself the “best little fair in Canada.” The Carp Farmers Market on the fairgrounds runs from May to October and is followed by the December Christmas Market.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History and its partners offer unique, history-based tours at home and abroad throughout the year.

Help support history teachers across Canada!

By donating your unused Aeroplan points to Canada’s History Society, you help us provide teachers with crucial resources by offsetting the cost of running our education and awards programs.