Born-again Bridges

None more so than in British Columbia, where great timber trestle bridges, monuments to the structural engineer's art, were built to span the gorges and chasms of a jagged landscape. Today, more shoes than steel wheels cross these bridges. Many have passed from rails to trails. Still, they remain what they always were — compelling forest icons.

Roland Brown walks along the railroad grade toward Cowichan Lake, checking on the old trestles. Next time he'll have his truck and tools, so he can fix some of the ladders down the steep creek banks, or respace deck ties to fill in holes left by rot and age.

A retired forest worker who volunteers for the Cowichan Valley Museum, Brown has lived in the Duncan area since the early 1960s. He wants to keep these crossings as routes for hikers and fishermen, and because they are links to a past when railroads were a spider web blanketing Vancouver Island and much of British Columbia.

Incorporating timber trestles, sometimes with steel elements, these railway bridges are historic examples of early railway engineering, unique monuments of the B.C. landscape. Now, heritage preservationists are working with all levels of government to preserve these structures, so essential to the linear hiking trails that the abandoned railways offer.

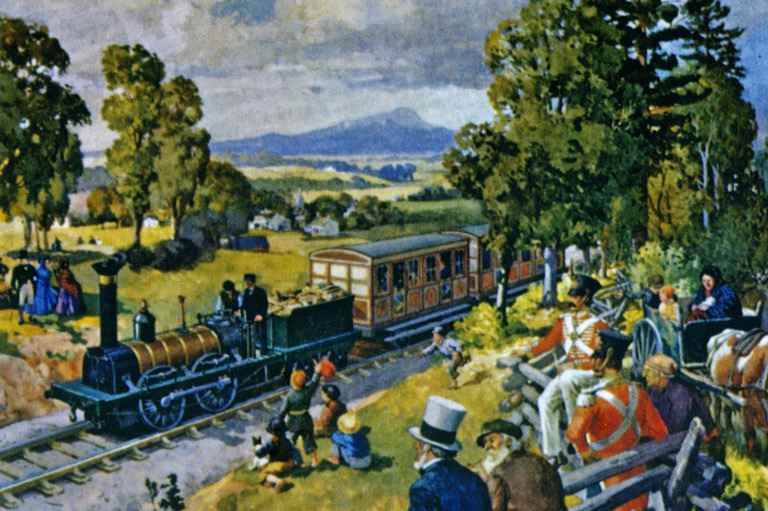

The grade Brown is walking was built by the original Canadian Northern Pacific Railway that struggled to be born during the years of World War I. The route from Victoria to Port Alberni was to travel inland through dense forest of Douglas fir, hemlock, and cedar to the west coast to get at stands of sitka spruce essential for warplane construction. But the line never got as far as Port Alberni.

While the roadbed was built most of the way, steel shortages delayed rail laying; only six kilometres of rail were done by Armistice Day, November 11, 1918. After that, as part of the new Canadian National Railway, the rails stretched to Cowichan Lake, Youbou, and finally in 1928, to Kissinger, at the lake's west end.

The trestle bridge looms out of the mist of a West Coast winter, leads us out of claustrophobic forest over a swollen river, a vertiginous drop to the rocks and rushing water. Unprotected by handrails, but massive in structural redundancy, the timber posts and bracing reach down through the regrowing bush to foundations on concrete — or simply to mudsills, now rotting into the soil.

Bracing hangs on a single bolt, struts are broken or sagging, but the main vertical frames appear intact, supporting the deck beams of creosoted wood or rusted steel. The rails are long gone, but we walk on the ties, ignoring the moving water far below.

The passengers of the 1920s must have felt that vertigo, looking out the windows of the self-powered gas railway car as it glided through stands of untouched conifers, then over the high trestle. The sixty-pound rail, 30 percent lighter than the rails of most main lines, added to the peculiar rocking gait of the car. The locals dubbed the car “Galloping Goose,” a name now attached to the Victoria-to-Leechtown hiking trail along the old grade.

The main line ran from Victoria to Youbou on the north side of Cowichan Lake, carrying freight and timber as well as passenger cars. In 1924, an eleven-kilometre spur line named Tidewater joined the line to Cowichan Bay on the eastern shore of Vancouver Island. Two freight trains per week, and as many as three logging trains per day, crossed these trestles. At the peak, eight logging companies worked along the railroad.

The gas-powered cars ran for only a few years, as competition from the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway forced an end to the unique passenger service in 1931. For over forty years the CNR continued to be it major transport route for logs and lumber.

However, by 1965, decreasing logging volumes and competition from highway freight carriers cut into business. Two trestles near Victoria failed safety tests and that sector was closed.

The wooden trestles were built from the timbers of the forest through which they passed. They were symbolic of the burgeoning forest economy; anything could be built with the massive trees.

Ralph Morris was regional engineer of bridges and structures for the CNR when he retired fourteen years ago, but he hasn't stopped thinking about “his” bridges yet. Spending his entire professional life in the bridge department, Morris wrestled with the problems of the railway’s structures in the West: how to keep them safe for increasingly heavy rail traffic.

Due to the uncertainty of future business on Island lines, he always had problems getting capital funds. Originally, the wooden trestles were built from the timbers of local trees. They were symbolic of the burgeoning forest economy; anything could be built with the massive trees.

Still, regular maintenance was needed. Whenever they had to repair the trestles, Morris specified creosote-treated timber. He wanted the structures to last.

And they have. The Kinsol trestle spans the Koksilah River at mile 51.1 (from Victoria). At 38 metres high and 188 metres long, Kinsol's centre span was reconstructed in 1935 to more accurately fit the alignment of the track.

New trusses were erected just above the river on concrete piers and a full trestle built above, the continuous trestle matching the long sweeping curve of the track. Since abandonment, the trestle has suffered more from vandals than from age, with two fires causing damage on the deck.

Trestles such as Holt Creek, at mile 59.7, were progressively improved using treated timbers. “We could do it out of operating money,” Morris recalls. “If we had had another year or two we could have finished.”

The creek bed is spanned by steel beams originally fabricated in 1887, then pirated from two disused bridges near Sidney, on a branch north of Victoria. But when the main line closed, the central timber trestle remained untreated.

Seldom did structural problems cause accidents. But in 1937 at Wolf Creek, mile 33.9 near Leechtown, runoff water and debris caused the footings to give way when Robert “Frosty” Winters drove his train across, and the locomotive crashed down.

Crew members cut telephone wires to call for help for the injured engineer. The most suitable ambulance was another train, but despite their efforts, Winters died in hospital in Victoria.

The CNR upgraded to larger steam engines like the M3-Consolidated and, after 1958, to 1,200-horsepower diesels. This meant heavier engines pulling bigger trains, loads that compressed the top caps over the piles. So, the tracks continually needed shimming.

The south section to mile 57.9 was finally closed in 1979, and from Youbou east to the ocean in 1988. Some members of the train crew took their wives along for the last ride down to Cowichan Bay. A perpetually troublesome creek at mile 62.5 had flooded gravel onto the track, causing a minor derailment.

The crew and their wives had to walk through the night to Deerholme, about eight kilometres away. Returning the next day by speeder, a small cart used by maintenance crews, the wives didn't want to cross Holt Creek trestle, which they had happily walked across in the dark.

Today, these sagging structures of a bygone era are regaining life. On the Galloping Goose Regional trail near Victoria, the high, steel trestle at Charters Creek has a new pedestrian deck. Todd Creek's timber trestle has been repaired, capable of carrying foot, cycle, and equestrian traffic and of course, its own substantial weight.

Both have solid handrails. Further north, the old grade, now owned by the province, is the future route of the Trans Canada Trail, scheduled to open next year.

There is a renewed interest in railroading on Vancouver Island. The E&N makes a daily run up-island, in summer for tourists and in winter for skiers. On the same line, the Pacific Wilderness Railway, using old CNR coaches, makes three tourist trips a day up scenic Malahat Mountain above fjord-like Saanich inlet.

The old CNR roadbed and the stalwart trestles are being used by the modern Galloping Goose Trail, and further north, they will soon become part of the Trans Canada Trail. The timber structures of the original railway, the trestles that engineers like Ralph Morris carefully guarded for decades, will regain their status as enduring forest icons.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!