Top 10 Business Deals

People have been doing business in Canada for a long time. Even before contact with Europeans, Aboriginal nations had vast trading networks stretching across North America.

Then the Europeans arrived. Driven by visions of wealth, they fished off the Grand Banks, they traded for furs with First Nations, and they explored icebound polar seas for what they hoped was a quick trade route to the riches of the Orient.

These early adventurers could not do these things with empty pockets; they required wealthy backers willing to put their money into high-risk ventures. The history of Canada is as much about entrepreneurs, bankers, and businessmen as it is about explorers, soldiers, and settlers.

Here we explore the business side of Canada’s development as a nation. Who started the first bank, the first stock market? How did the rules of international trade evolve? Why was wheat, for a time, the linchpin of Canada’s economy?

Joe Martin, the director of Canadian business history at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, helps answer these questions by examining Canada’s top ten historically significant business events.

These gamechanging moments — which are commemorated in a mural at Brookfield Place in Toronto — were chosen by Martin and a panel of business leaders that included Purdy Crawford, William Dimma, Hal Jackman, and Lynton “Red” Wilson. They are presented in chronological order.

Knowledge of Canada’s business past brings greater understanding to the somewhat breathtaking events taking place today. As Martin points out, Canada’s place in the world is changing as the planet moves towards a borderless globalized economy.

1670: The incorporation of the Hudson’s Bay Company

North America’s oldest corporation got its start when two French-Canadian coureurs de bois — Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard Chouart, Sieur des Groseilliers — turned their backs on New France after being fined for their trading exploits. The pair travelled to London to seek help from the English and found a receptive audience in the court of King Charles II.

The king’s cousin, Prince Rupert, and other courtier investors outfitted two ships that were to sail to Hudson Bay in 1668. The Eaglet was forced back by heavy seas, but the Nonsuch made it and returned to London the following year laden with furs.

On May 2, 1670, the king granted a royal charter to the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading into Hudson’s Bay Prince Rupert became the company’s first governor, and the chartered territory was called Rupert’s Land. The charter awarded the company the sole rights of trade and commerce in the Hudson Bay drainage basin, a vast area of 3.8 million square kilometres, forty percent of present-day Canada.

In its early years, the company engaged in armed struggles with the French. The conflicts left the company in a perilous state, and no dividends were paid for two and a half decades. Thereafter the company had a virtual monopoly on the British North American fur trade, although it continued to face competitive challenges.

As the nineteenth century progressed, the company became one of the most important in all of Canada, but there were changes afoot. In 1863, the International Financial Society, a British investment group, acquired the company. This marked a shift away from the fur trade into real estate as the West began opening up to settlement.

In 1869, the newly created Dominion of Canada purchased Rupert’s Land for £300,000 in what was, in terms of land area, the largest real estate transaction in history. The purchase increased the size of Canada sixfold. Meanwhile, the HBC retained some prime farmland in the region and held on to its successful fur-trading posts.

Over the years, the company diversified and became a key player in the retail scene. In the latter part of the twentieth century the Bay expanded eastward from its Winnipeg base, acquiring major retailers in Montreal and Toronto, including Zellers and Simpsons.

More recently North Carolina-based Maple Leaf Heritage Investments purchased the Bay in 2006. Two years later, it was sold to NRDC Equity Partners, a private equity firm in New York. Then, in 2011, Minneapolis-based retail chain Target purchased the leases of 220 Zellers store locations in Canada.

Today the Hudson’s Bay Company remains one of Canada’s pre-eminent retail chains. And, as North America’s oldest corporation, it has a rich legacy that includes opening up much of Canada’s North and West to trade and commerce. Important Canadian cities such as Winnipeg, Edmonton, and Victoria were built on the sites of what once were Hudson’s Bay forts.

1817: The launch of Canada’s first bank

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the provinces of Canada did not have a well-functioning financial system. As a consequence, Montreal merchants had great difficulty in financing their exports to Britain while paying for imports. Therefore, a market developed in promissory notes.

There were a number of attempts to establish banks. The first to succeed was the Bank of Montreal, incorporated by John Gray and other prominent Montreal businessmen in 1817. The end of the War of 1812 was a factor because during the war, army bills were in wide circulation and businesses became accustomed to the ease of using paper currency

The bank’s charter, issued in 1822. was modelled on that of the First Bank of the United States. It included restrictions on share ownership and did not permit the bank to undertake any other business activities. The paid-in capital had to be in specie — meaning in coin, often Spanish gold doubloons, rather than paper money.

Another critical feature of the charter was that it was limited to ten years. Because of the shortage of capital in Canada, most of the bank’s financing came from wealthy Americans. In the early years, the bank enjoyed the privilege of being the exclusive banker to the government. It lost no time opening branches in Kingston and Quebec City.

By the time of Confederation, the Bank of Montreal was by far the largest in Canada, holding twenty-five percent of all bank assets.

When it came time to pass a Bank Act for the new Dominion of Canada, the Bank of Montreal attempted unsuccessfully to have its role be like that of the Bank of England, with the other banks restricted to a minor role as local banks.

As the twentieth century progressed, the bank shifted many of its functions to Toronto. In 1984, the bank moved into the U.S. market, acquiring the Harris Bank in Chicago. In 1998, the Bank of Montreal and the Royal Bank of Canada tried to merge, but the federal government blocked that move.

In late 2010, the bank acquired a major Wisconsin bank, which doubled its presence in the important U.S. market. With that acquisition, the Bank of Montreal is now not only one of the big five banks in Canada but also the tenth-largest commercial bank in North America.

As the largest bank in the country for the first century of its existence, the Bank of Montreal had a profound influence on government financial policy.

1874: The founding of the Montreal Stock Exchange

The roots of Canada’s first stock exchange go back to 1832, when a group of Montreal businessmen engaged in informal stock trading at the Exchange Coffee House. The formation of a brokers’ association followed in 1849.

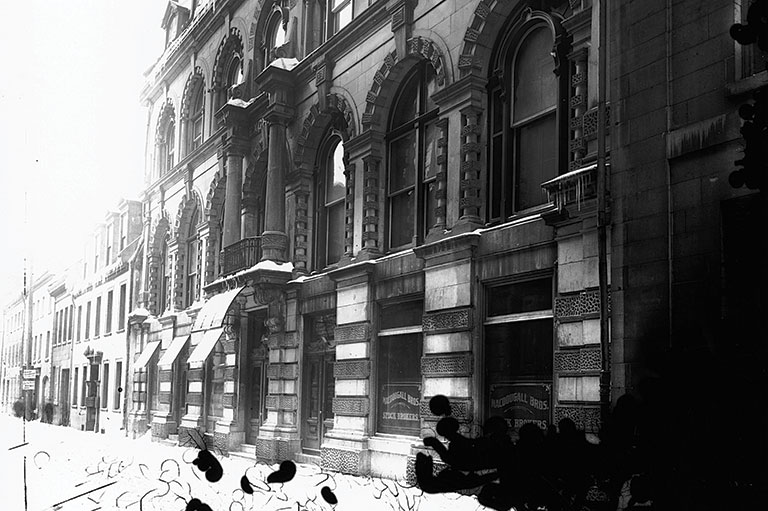

A small group under the leadership of stockbroker Dugald Lorn MacDougall created the Montreal Stock Exchange, which was incorporated in 1874. The exchange grew rapidly, broadening from trading in railway and bank stocks to public utilities, mining, and the newly emerging manufacturing sector. Montreal’s St. James Street (rue Saint-Jaques today) — where much of the trading occurred — became the Wall Street of Canada. In 1904, the exchange moved into its own building at 453 St. Francois-Xavier Street — now the Centaur Theatre.

The Montreal exchange was hard hit by the economic turbulence of the first decade of the twentieth century, particularly during the 1907 credit crisis, when share volumes declined by nearly sixty percent. However, by 1909, annual volume exceeded 3.3 million shares.

The Great Depression changed everything. Trading volumes in Montreal declined by nearly ninety percent between 1929 and 1932. The Toronto Stock Exchange (TSE) also suffered but emerged from the debacle slightly larger than Montreal, something that would have been difficult to imagine in the 1920s. As the twentieth century progressed, Toronto eclipsed Montreal as the financial and commercial capital of Canada.

The year 1999 was momentous for stock exchanges in Canada. Montreal celebrated its 125th anniversary and became Canada’s financial derivatives exchange. At the same time, through a realignment plan, the TSE became Canada’s sole exchange for the trading of senior equities, and the Vancouver and Alberta stock exchanges merged to form the Canadian Venture Exchange.

The founding of the Montreal Stock Exchange was an important step in the evolution of capitalism in Canada. Canada’s exchanges have since moved towards being part of a much larger international body, as the globalization of world capital markets continues.

1879: The inception of a truly Canadian economy

The National Policy was the most significant economic policy in Canadian history in that it committed the country to an east-west economic structure that resisted the pull of the United States. Sir John A. Macdonald designed the policy as he prepared for a federal election that would see him return to power in 1878.

The National Policy consisted of three interrelated parts: the settlement of the West; the building of a transcontinental railway; and the adoption of a protective tariff. Despite a change in government in 1896, the policy was continued and lasted essentially until the 1989 Free Trade Agreement with the United States.

The requirements for the first part of the National Policy — western settlement — were already in place. Land was available as a result of the purchase of Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1869. And the 1872 Dominion Lands Act set the conditions for offering free land to settlers.

A transcontinental railway — which British Columbia had set as a condition for joining Confederation in 1871 — was needed to settle the lands. Attempts to build an east-west rail link started in the 1870s, but little progress had been made. The third part of the National Policy — a protective tariff to build up domestic industry — was a new initiative.

Once back in power, Macdonald moved quickly on both the railway and the tariff. In 1879, tariffs were raised to thirty-five percent on manufactured imports and were imposed on an expanded list of products.

While successful in building up domestic industry, the policy also led large American corporations to establish branch plants in Canada in order to avoid the tariff. The question of free trade versus protectionism continued to be contentious in Canada well into the twentieth century.

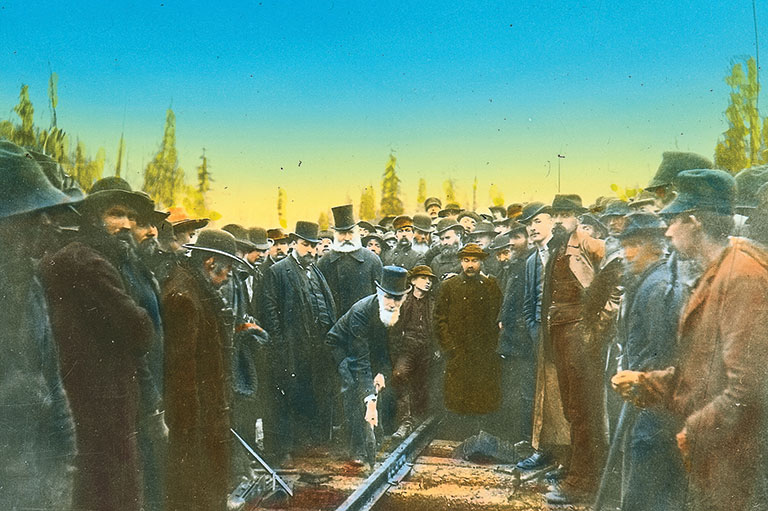

Meanwhile, the railway became a reality. The Canadian Pacific Railway Company (CPR) was incorporated in 1881. After a flurry of track-building activity over thousands of kilometres of difficult terrain, the last spike was pounded in 1885. The CPR became a highly successful company — by the beginning of the twentieth century it was by far Canada’s biggest corporation.

The National Policy had far-reaching effects, resulting in massive investment, immigration, and economic growth. Classical economists criticized it for driving up costs and insulating Canadian businesses behind a tariff wall. However, its principal legacy was to cement Canada’s westward territorial expansion and to create an East-West economy.

1896: The beginning of the wheat boom era

From 1896 to 1913, Canada experienced an extraordinary period of economic growth. This period is commonly referred to as the wheat boom era.

In the decade prior to 1896, the Canadian economy was stagnant. However, a technological innovation known as the Hungarian milling process would change Canada’s fortunes. The system was the most significant milling innovation in centuries and was a necessary precondition for the Canadian wheat boom because it improved the milling of hard wheat, which grew well on the Canadian prairies.

The leaders in adapting the improved milling process in Canada were the Ogilvie brothers of Montreal. They moved into Manitoba, building a mill in Winnipeg in 1882 and eventually dominating the grain trade of Western Canada.

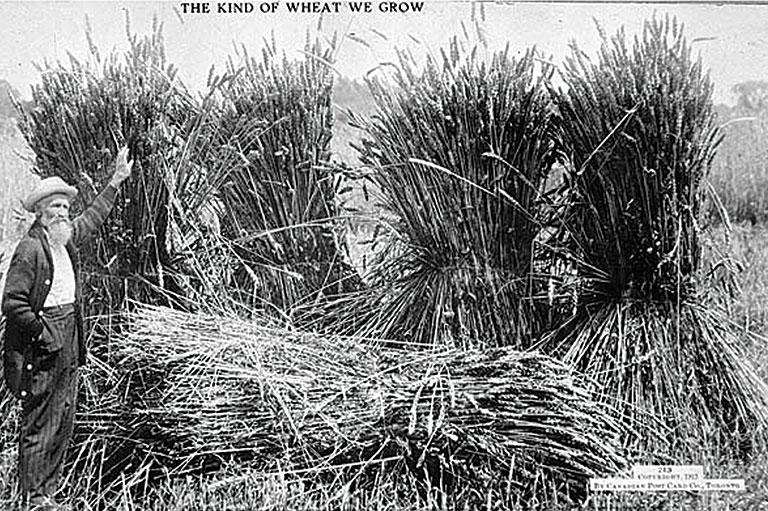

By the mid-1890s, No. 1 Manitoba hard wheat had developed an excellent international reputation for milling into flour. This marked a revolution in thinking, for the quality of prairie wheat had previously been regarded with suspicion.

This development, combined with the end of free land in the United States and a concentrated effort to attract settlers to Canada, finally resulted in the settlement of the Canadian West. The results were stunning — settlers flocked to the West from Ontario, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Europe. In the first decade of the twentieth century, Canada’s population increased by 1.9 million people — with nearly half of the increase occurring in the West.

While people were pouring into the Prairies, the economy boomed — GDP per capita nearly doubled. That’s not to say there were no bad years — the 1907 credit crisis, for instance, contributed to one of the worst economic years in Canadian history. Yet wheat was king. The introduction of early maturing Marquis wheat in 1907 — developed by Charles Saunders, director of the Experimental Farms Service — helped make wheat Canada’s main export, surpassing lumber.

Even post-1913, when manufacturing began to surpass agriculture in terms of economic importance, wheat exports remained important. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, wheat sales to China marked a first step in the growth of cultural ties between the two countries. Today, Canadian wheat is sold throughout the world.

The wheat economy had a big impact on Canada, drawing tens of thousands of people to the Prairie region and contributing immensely to the economy.

1934: The creation of Canada’s central bank

The creation of the Bank of Canada was probably the most important public policy initiative of the first half of the twentieth century. The central bank was formed in 1934 in reaction to the Great Depression, when the necessity for direct government control over monetary policy became apparent.

The idea of a “big government bank” was first advocated in Parliament in 1913 by independent MP William F. Maclean. The topic was revisited in 1919, when Finance Minister William Thomas White asked Canada’s bankers for recommendations on how to establish one. However, the Canadian Bankers Association opposed the idea.

The western Progressive Party included a central bank as part of its party platform in 1925. By the 1930 election, with the economy dominating political debate, the idea re-emerged.

In 1933, during the fourth year of the Depression, Prime Minister Richard Bennett established a Royal Commission on Banking headed by Scottish jurist Hugh Macmillan. Within two weeks of hearing its final submission, it formally recommended the creation of the Bank of Canada. The new bank would regulate the volume of credit, cooperate with other nations, and issue tender.

Bill 19 to create a privately owned central bank was introduced in February 1934. In the ensuing debate, the prime minister reminded members of the banking community who continued to oppose the central bank that his government was not under their control. In 1938, a new government nationalized the institution, and it remains that way today.

Initially the Bank of Canada served more as a financial advisor to the federal government than as a decider of monetary policy. In its first twenty years, interest rates were changed only twice.

Over the years, the bank has evolved. In 1991, it became the world’s second central bank to set a target for inflation. Today the Bank of Canada is responsible for price stability, regulates the level of inflation by controlling money supplies by means of monetary policy, and plays a vital role in the operation of the economy.

The Bank of Canada Act has been amended numerous times, but the wording of its preamble remains the same as it was in 1934. It says the bank exists "to regulate credit and currency in the best interests of the economic life of the nation.”

1947: The discovery of oil at Leduc, Alberta

The invention of the automobile, with its thirst for petroleum products, resulted in a great transformation of Canada’s economy in the twentieth century. Yet in spite of the fact that Canada was home to the world’s first commercial oil well — at Oil Springs, Ontario, in 1858 — and had the largest oil well in the British Empire — Turner Valley, Alberta, discovered in 1914 — Canada remained a net importer of oil until mid-century.

That started to change on February 13, 1947, when, after 133 consecutive dry holes, Imperial Oil struck it rich at Leduc, Alberta. So important was the find that the Canadian oil industry uses it to reference time — "before Leduc" and "after Leduc." Leduc ushered in Alberta’s golden age of oil.

The Leduc field was estimated to possess two hundred million barrels of oil — a huge find by Canadian standards. Leduc was soon dwarfed by even larger discoveries. Five years after Leduc, oil production equalled coal production in Canada. By 1955, oil was three times greater than coal.

After Leduc, Imperial Oil — a Canadian company established in 1880 — sold its stake in its South American subsidiary International Petroleum, even though the subsidiary had ten times more production than the company had in Canada. Imperial did this to focus on its aggressive oil-finding efforts in Western Canada as well as to build refineries and pipelines.

Imperial Oil was not alone. Massive foreign direct investment and expertise came into Canada after Leduc. Most of the more than $2 billion in capital that had flowed into the Western Canadian oil patch by 1954 came from big international oil companies. Between 1947 and 1956, the capital employed in Canada’s oil and gas sector was ten times the amount invested during the entire period between the Turner Valley discovery in 1914 and the Leduc strike in 1947.

The discovery at Leduc marked a historic shift from coal to oil as the principal fuel supply of Canada, just as, fifty years earlier, there had been a major shift from wood to coal. Within five years, Canada moved from importing ninety percent of its oil requirements to being a net exporter. Today, Canada is the second-largest gas exporter in the world and by far the major exporter of oil to the United States.

1965: The signing of the Auto Pact

The arrival of the automobile in the early twentieth century introduced a new dimension to trade relations between Canada and the United States. Originally, tariffs on automobiles were the same as those placed on horse-drawn carriages and wagons. But this market protection was to prove counter-productive for Canada, as car-making became one of the most important industries in twentieth-century Canada.

By 1960, Canada was running a large trade deficit with the United State. The main reason was a trade imbalance in the auto sector. This led to the appointment of a Royal Commission, which concluded that the future lay in narrowing Canadian lines of production and increasing exports.

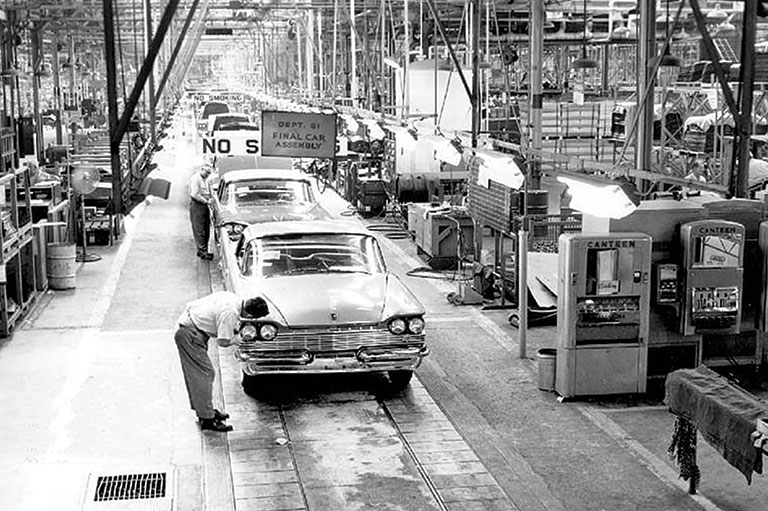

In January 1965, Prime Minister Lester Pearson and American President Lyndon Johnson signed the Canada-U.S. Automotive Products Trade Agreement — commonly known as the Auto Pact. The agreement provided for duty-free passage of automobiles across the border. The Auto Pact was the most significant trade development in thirty years and would remain so until the Free Trade Agreement of the late 1980s.

It did not take long for Canada to benefit. In 1964, Canada had a $618-million trade deficit. By 1970, the trade deficit had disappeared, with Canada realizing a modest trade surplus. Because of increased efficiencies, auto prices dropped and the industry expanded. In fact, Canadian vehicle production in the late 1990s was nearly twice Canadian sales — the balance was exported primarily to the U.S.

The Auto Pact shifted Canadian automobile and parts production towards a North American and global orientation. Because the pact eliminated tariffs but maintained production requirements, there was a massive growth in assembly operations in Canada. Just as importantly, the pact allowed Canadian parts companies — such as Magna, Linamar, and Wescast — to flourish on a global scale.

Most significantly, the Auto Pact paved the way for free trade with the United States and was in many ways a precursor to Canada’s place in a globalized and borderless economy.

1967: The development of the Athabasca oil sands

When eighteenth-century fur trader Peter Pond remarked upon the "springs of bitumen" he saw in northeast Alberta, he probably couldn’t have foreseen how important they would become to Canada in the twenty-first century.

The Athabasca oil sands region is today one of the largest proven oil reserves in the world. This makes Canada an important player on the global energy stage. The amount of recoverable oil in the oil sands is estimated at 170 billion barrels — enough to supply oil needs in the United States for twenty years. And the exploitation of the sands will permit Canada to export oil to China as well as to the United States.

Originally called tar sands — even though they contain no tar — the oil sands attracted development early in the twentieth century In 1913, federal government engineer Sidney Ellis began experimenting with a hot water floatation process to separate the oil from the sand. Others followed, using similar extraction principles, but profits from commercial exploitation proved elusive.

The tide began to turn in 1962, when the Alberta government announced a policy for the orderly development of the oil sands. The first commercial development began in 1967, when Great Canadian Oil Sands, now Suncor, opened the world’s first oil sands operation on the banks of the Athabasca River north of Fort McMurray. In the 1970s, Syncrude, a consortium of six companies that included Imperial Oil and Petro-Canada, began operations at Mildred Lake, north of the Suncor plant. Syncrude shipped its first barrel in 1978.

Since those early beginnings, billions of dollars have been invested in the oil sands. And as oil prices have risen spending has accelerated — from over $4 billion annually in 2000 to $13.5 billion in 2010. Large chunks of that spending have gone towards leading-edge technology to mitigate environmental damage from mining and processing.

Oil sands development has profoundly changed Canada and its place in the world. The economic balance has shifted westward as tens of thousands of people have migrated from Eastern Canada to work in the oil industry Internationally, rising demand from China, as evidenced by Chinese investments in the oil sands, foreshadows the day when China will join the United States as Canada’s major export market for oil.

1989: The implementation of the Free Trade Agreement

Canada has been a trading nation since its inception, and most of its trade has been with the United States. Over the decades, trade relations between the two countries have been marked by ups and downs.

One of the first attempts to ease trade restrictions came with the Reciprocity Treaty of 1854. Opposition from American protectionists resulted in the U.S. unilaterally abrogating the treaty in 1866. When attempts to negotiate a new agreement failed, Canada introduced a protective tariff in 1879.

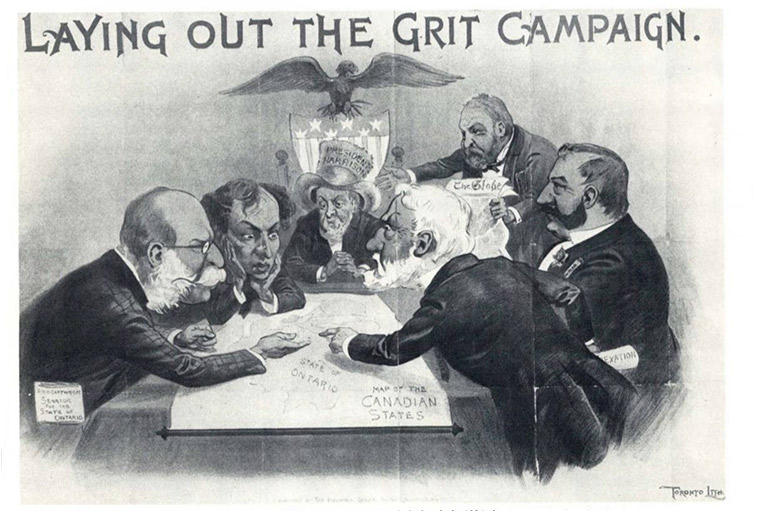

Efforts to secure freer trade continued, and Canadian Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier returned from Washington in 1911 with an agreement that lowered or eliminated duties on many products. But the unratified treaty became an election issue, and voters tossed the governing Liberals out of power, effectively quashing free trade for almost another eight decades.

With the Great Depression, Canada entered the worst economic period of its history as both countries introduced protective tariff policies that stifled growth.

The period from the mid-1930s to 1980 was marked by trade liberalization both bilaterally and multilaterally.

By 1985, the Royal Commission on the Economic Union and Development Prospects of Canada was calling on the government of Canada to take a leap of faith and enter into a free trade pact.

After many twists and turns, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and U.S. President Ronald Reagan signed the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) in October 1987. In an election held the following year, the FTA became the defining issue, with opponents arguing that Canada would lose control over its political as well as its economic future. In the end, free trade won out.

The FTA came into effect on January 1, 1989. When a new Liberal government came into power in 1993, it did not rip up the FTA but instead embraced it. A year later, the FTA was expanded as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which included Mexico as well.

Canada’s trade with the United States saw a dramatic increase. By the early twenty-first century, Canada was both America’s largest customer and largest supplier.

The FTA’s biggest impact was in the manufacturing sector, which saw significant rationalization, including the accelerated disappearance of branch plant operations in Canada.

Canada-U.S. trade suffered a setback with the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. And recent American actions — such as the Buy American policy and delays in approving the Keystone XL Pipeline — have been unsettling for Canada.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!