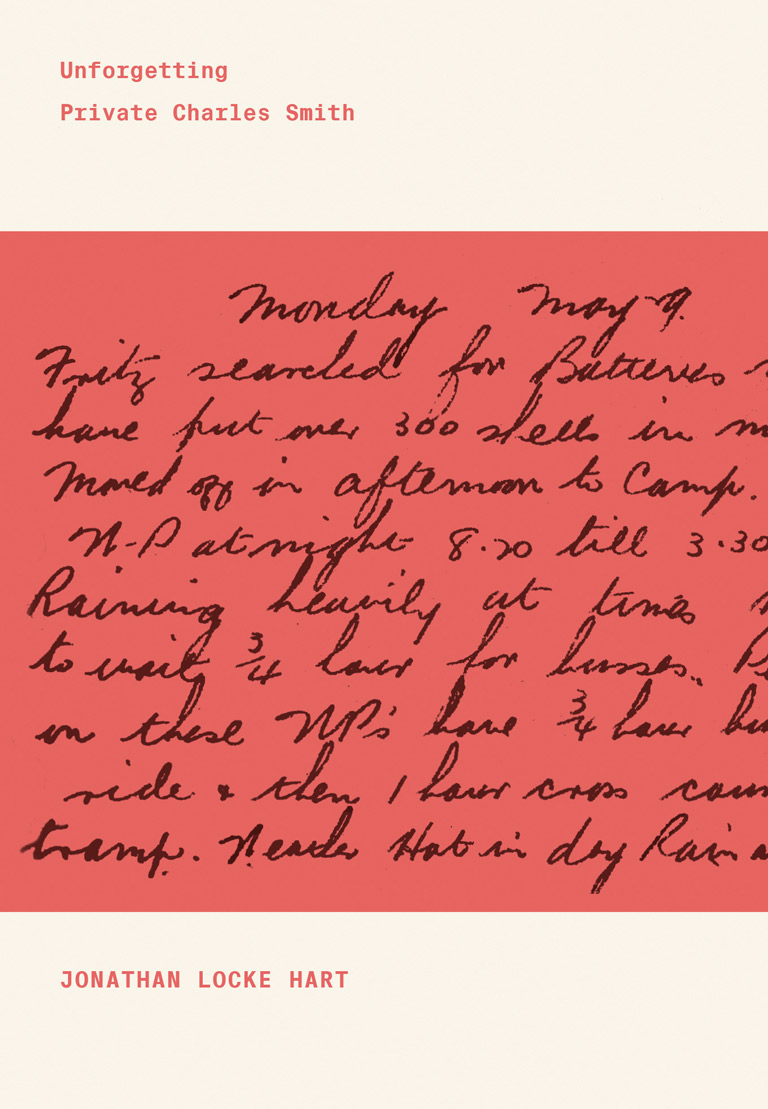

Unforgetting Private Charles Smith

Unforgetting Private Smith

by Jonathan Locke Hart

AU Press,

76 pages, $19.99

A double review with

Invisible Scars: Mental Trauma and the Korean War

by Meghan Fitzpatrick

UBC Press,

194 pages, $24.95

Often referred to as the “forgotten war,” the Korean War conflict effectively lasted only three years, from 1950 to 1953. However, the massive bombing and brutal fighting in an unforgiving, mountainous landscape, with punishingly cold winters and intensely humid summers of flooding, rodents, and insects, exacted an incredible toll of more than four million dead and wounded, many of those civilian casualties.

As historian Meghan Fitzpatrick points out in her well-written and insightful study, while much has been said about war trauma, little attention has been given to the soldiers who served in the Korean War, and even less to the British Commonwealth Division and the medical teams that supported it. Canadians played a key part, composing three quarters of the divisional psychiatrists.

In Invisible Scars: Mental Trauma and the Korean War, Fitzpatrick examines the “unprecedented experiment in integration and inter-allied cooperation” as part of the United Nations response to the invasion of South Korea by North Korea. In fact, she writes, the Korean War represented a “pivotal turning point” in Western battlefield medicine, with higher rates of soldiers returning to battle and relatively fewer battle mortalities due to mobile hospitals, surgical advancements, and helicopter airlifting.

Added to the large U.S. contingent of eventually nearly two million combatants, approximately 145,000 troops were deployed from the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand and formed the 1st British Commonwealth Division in 1951. They were reported to be “the best,” Fitzpatrick writes: “Admired by allies and enemies alike, the officers and men of the division were well known for their discipline and professionalism.”

Her chapter on efforts to sustain soldier morale in the division is especially enlightening. Limited tours of duty were implemented by leadership, based on previous wartime experience and an astute analysis of the ambiguous, extended nature of the conflict, which created a strain on collective spirits. Though mental health was considered, the treatments continued to be directed towards returning soldiers to the field.

The conflict mainly took place at night, with heavy shelling that could last for hours and that resulted in vicious shrapnel injuries. The extreme climate led to other injuries such as frostbite, trench foot, and immersion foot. These factors combined to create overwhelmingly stressful conditions that had impacts long after the soldiers returned home. The ultimately unresolved nature of the conflict, as well as an adversarial pension system, meant there was little practical, psychological, or moral support for the repatriated soldiers, with enduring effects on their mental health.

If, as Fitzpatrick notes, the wounded soldier is at the heart of her study, then the forgotten soldier is at the heart of another, very different book. Unforgetting Private Charles Smith provides a unique look at the year-long diary of a twenty-two-year-old First World War trench soldier. Records show that Smith died at the Battle of Mount Sorrel, the “fiercest bombardment yet experienced by Canadian troops,” according to Veterans Affairs Canada. Men were “literally blown from their positions” as entire sections of trench were destroyed.

The diary inscription requests its return to Private Charles Smith’s mother in the case of his death. As if honouring that request, poet and scholar Jonathan Locke Hart arranges selected diary entries into a long poem, compelling readers to attend closely to the words. It’s an exercise “against remembrance,” as Hart titles the accompanying essay in this slim volume.

By their very nature, and despite good intentions, “memorials confer anonymity,” requiring lists of names and “the transformation of human anguish into heroism,” the author writes. Hart is after something different. Through Smith’s mundane descriptions of the weather and of daily life in the trenches, a remarkable, moving portrait emerges in tribute to the particular life of one ordinary soldier.

“It is hard to realize we are at war,” Smith writes in September 1915, three months into his deployment. Soon enough, the tone shifts, and we get the sounds and smells, the lived experience of the trenches. “Some night last night,” he writes. “We had stripped and slept in underwear./ It started to rain and rained all night.// I slept in a pool of water./ Weather rotten.” The descriptions become more haunting: “I heard the moan/ Of the air as the shell cut through.”

In May 1916, he writes, “Work party: we have had a jake time./ There was hardly any shelling and only/ Two casualties in eight days.// One killed. One wounded.// We moved up to supports on Hell Street./ A good dugout. A shell landed near us,/ A piece caught me in the back only making// A bruise. I dropped the wine and ran like anything/ For the trench. I wanted to get away/ From the place. I suffered a little from shock.” Private Charles Smith died on June 2, 1916, two days after his final diary entry.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement