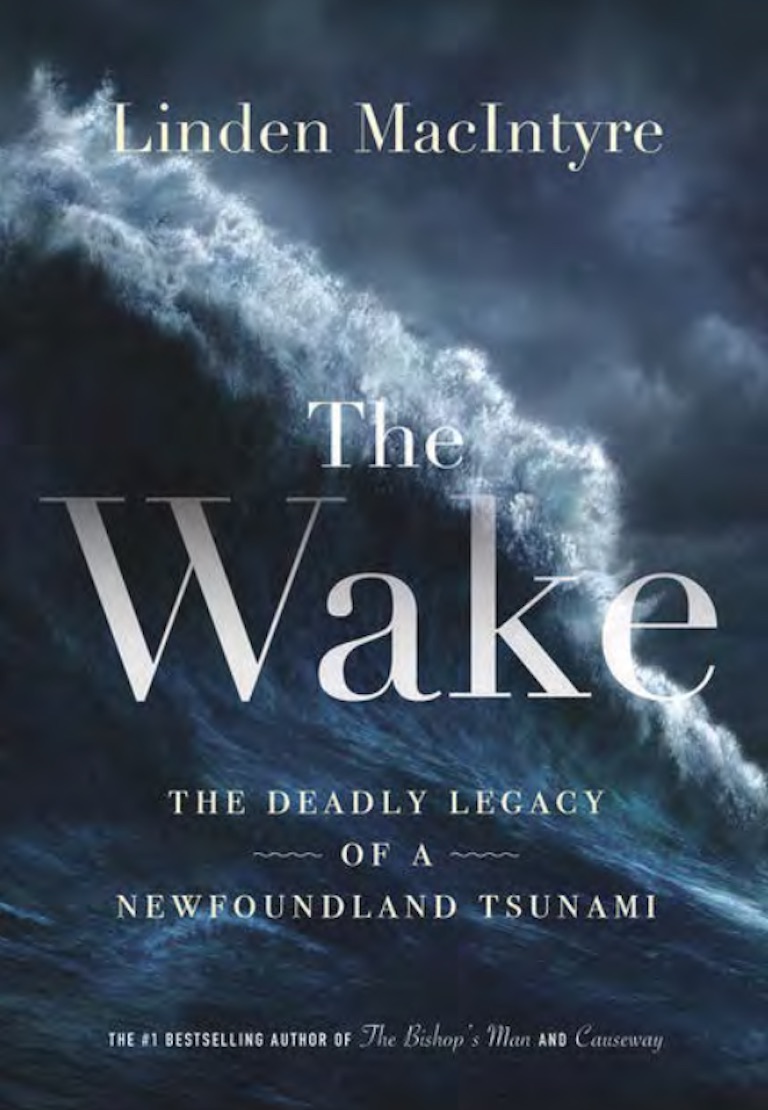

The Wake

The Wake: The Deadly Legacy of a Newfoundland Tsunami

by Linden MacIntyre

HarperCollins Canada,

399 pages, $32.99

Fisherman Patrick Rennie and two of his sons were on high ground when three giant waves battered their Newfoundland outport home. The third carried it into Lord’s Cove. Rennie’s four-year-old daughter was plucked from the half-submerged building, but his wife and three other children were dead.

They were among twenty-seven people who died in November 1929 when a 7.2-magnitude undersea earthquake unleashed towering tsunamis on the isolated Burin Peninsula, shattering houses and fishing gear and wiping out livelihoods. Linden MacIntyre shows that this was only the first of two disasters to befall the hardscrabble region. The other involved something human-made — mines established in the community of St. Lawrence to extract the mineral fluorspar, which offered jobs and hope to unemployed fishermen. Radiation and dust slowly killed hundreds of the miners. “It started with an earthquake,” he writes of this twin disaster. “It ended with a plague.”

MacIntyre, a familiar face and voice thanks to a career as a CBC investigative journalist, won the Scotiabank Giller Prize for his novel The Bishop’s Man. He returns to hisnon-fiction roots in The Wake, which combines a riveting story of loss and survival with a searing indictment of the development-at-any-cost mentality that has ruined lives and the environment in so many remote communities. It’s “a story that has relevance today,” he reminds us, “for vulnerable workers in many places, in Asia and Africa and Latin America.”

Newfoundland was destitute in the 1930s. Markets for cod collapsed during the Great Depression, catches were poor — likely due in part to the tsunami’s lingering impact — and the bankrupt government was dissolved, subjecting a self-governing dominion to the humiliation of colonial-style direct rule from Britain. Enter Walter Seibert, a twenty-something opportunist from New York who acquired mineral rights in St. Lawrence for a pittance and exuded the confidence and smarm, MacIntyre notes, of the “shyster” he most certainly was. With no pesky government inspectors looking over his shoulder — and no workplace-safety laws to rein him in if there had been — Seibert’s mines became death traps. The men of St. Lawrence made a Faustian bargain to risk a premature death as the price of earning a living.

The tsunami did its deadly work in minutes. The second disaster took years to play out, as men working in the poorly ventilated mines slowly succumbed to cancer and lung disease. Warnings were ignored. Protests and complaints were brushed aside. By the time investigations confirmed the link between working conditions and miners’ deaths, there was no one left to hold accountable for the carnage. Among the dead was Patrick Rennie, whose family was decimated by the tsunami; he joined his neighbours in the mines and died in 1951 at age sixty.

For MacIntyre, this is a personal story. He grew up in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia — his soothing accent assures visitors to the island that “Your heart will never leave” in tourism advertisements on television — but he was born on the Burin Peninsula six years before Newfoundland joined Confederation in 1949. His father, Dan, was working in the St. Lawrence pits at the time and was only fifty when he died.

In short sections titled “Conversations with the Dead,” MacIntyre offers his best recollection of long-ago conversations with his father. To his regret, these discussions rarely delved into the specifics of the risks of working in St. Lawrence, but they allow him to explore unanswered questions about what happened and why. Each section appears in italics, clearly demarcating these meditations from the scrupulously researched historical narrative.

MacIntyre’s storytelling is as powerful and relentless as the wall of water that left so much devastation in its wake. This heartfelt account is a sobering reminder of nature’s fury and of the human cost of greed and corporate indifference.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement