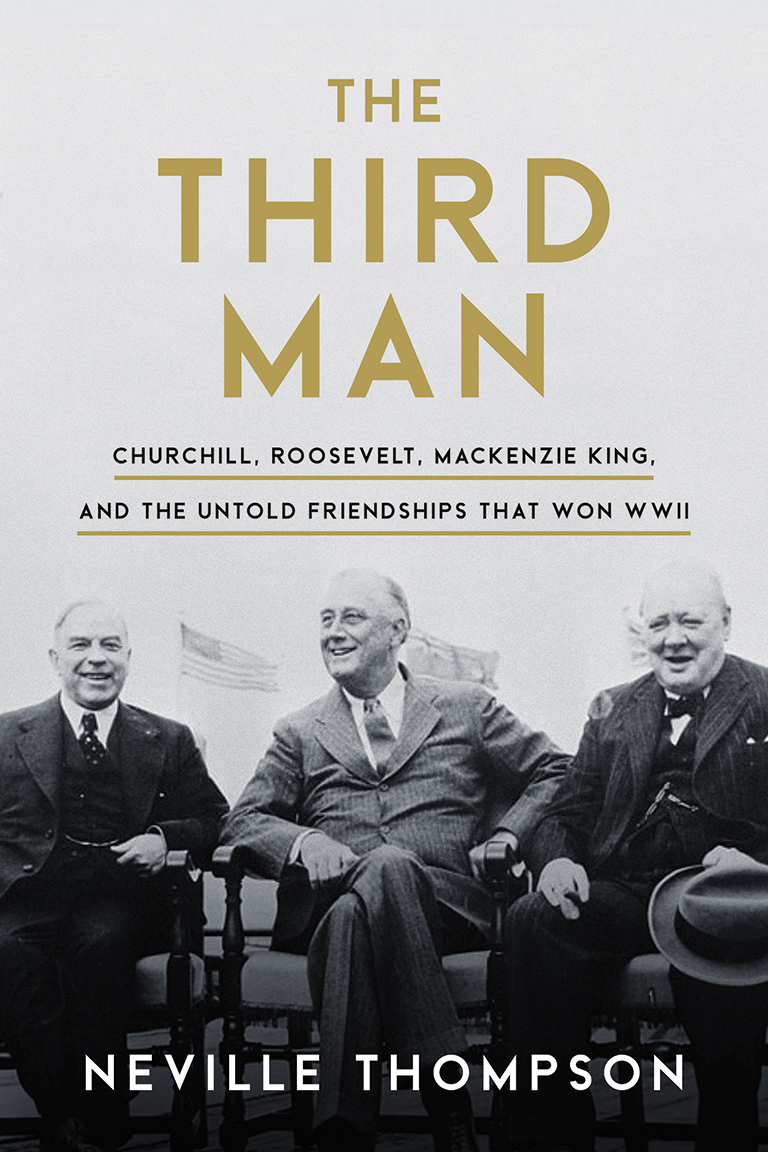

The Third Man

The Third Man: Churchill, Roosevelt, Mackenzie King and the Untold Friendships that Won WWII

by Neville Thompson

Sutherland House

508 pages, $39.95

With the world’s fourth-largest air force and fifth-largest navy, and with more than a million men and women under arms during the Second World War, Canadians fought in every theatre of the conflict except for Russia. This amazing achievement by a nation of barely twelve million people was only part of the story, however. The role played by Canada’s bland and inscrutable prime minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King, in the delicate diplomatic dance between the two key Western leaders, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, was also significant.

It has been said that Canada’s chief mission was to serve as an “honest broker” between Britain and the United States, explaining each country to the other. This is largely a fiction. Yet, as Neville Thompson makes clear in his book The Third Man, it was King’s conviction that the purpose of his life was to bring Britain and the United States into “close harmony.”

The Third Man draws on the thirty thousand typewritten pages of King’s voluminous diaries, but to say that the book is a reprise of those entries would be unfair. It is really a story of the Second World War in which Thompson amplifies, interprets, and questions the former prime minister’s diary notes and places them in the context of the relationships between and among him, Churchill, and Roosevelt. Thompson, who is an emeritus professor of history at the University of Western Ontario, sees King as standing out for his “educational attainments and worldliness.”

Mackenzie King met Winston Churchill in 1900 when Churchill, fresh from his South African war heroics, reached Ottawa on a speaking tour. In London in 1906, King, then a Canadian civil servant, sought Churchill’s help in stopping Asian immigration to Canada. If not a supplicant, King was always the junior partner in their relationship; yet he nonetheless opposed Churchill’s prewar anti-appeasement attitude. And when King George VI, on his visit to Canada in 1939, said he would not wish to appoint Churchill to any high office, King told the monarch that he was “helping to save the world.” At that point, King regarded Churchill as “one of the most dangerous men I have ever known.”

King’s relationship with Roosevelt began when the newly elected U.S. president invited him to Washington in 1932 to discuss a trade agreement. By the time it was signed, the two men had become friends. King urged a similar agreement on Britain, and, when that took effect, he was convinced that he had played a “real part in bringing these three countries together at ... the most critical time in the history of the world.”

Roosevelt, mindful of isolationist sentiment in the United States, used King to convey messages to Churchill that the president felt could not be issued in his own name. One such communication noted that, if Britain fell, the Royal Navy would be allowed to operate from U.S. ports. King considered the message the “most significant of any that has thus far crossed the ocean.”

King was a frequent visitor to the White House and usually concluded those journeys by vacationing in Virginia or Georgia — even at the height of war. Roosevelt made several trips to Canada, including two wartime conferences with Churchill in Quebec City. King never sat in on these meetings but was made aware of the content of the discussions. Roosevelt suggested King as the possible moderator for a future United Nations that would ensure world peace through co-operation between the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union, and China.

Readers with a serious interest in Canadian history will find The Third Man engrossing. Others, to whom the Second World War is but a relic of the past (and who too often view Remembrance Day as a glorification of war) may find it hard going. But, if they read — or at least skim — this book, they will come away with an appreciation for the daunting challenges faced by three men of unusual personality and character in the great test of freedom versus oppression.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement