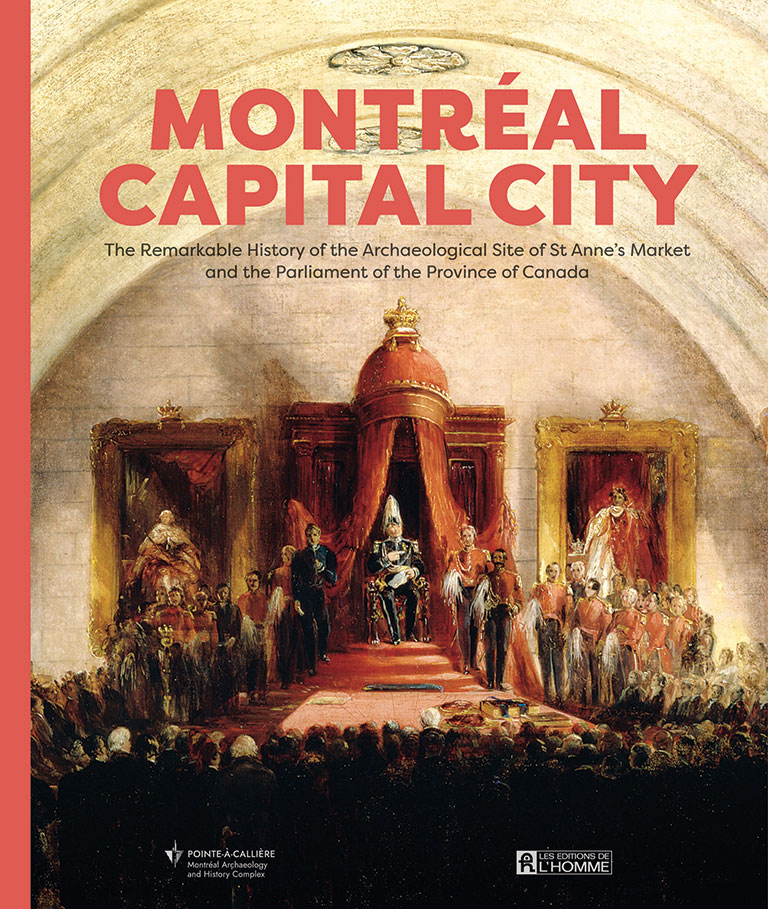

Montréal Capital City

Montréal Capital City: The Remarkable History of the Archaeological Site of St. Anne’s Market and the Parliament of the Province of Canada

edited by Louise Pothier

Éditions de l’Homme

238 pages, $46.95

Joni Mitchell sang, “You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.” And, long ago, Canadians paved Parliament and put up a parking lot. They’d already burned down the building. Now, 173 years later, this remarkable book recreates what was lost.

It happened in Montreal, and the fire was no accident. One dark night in 1849, a violent anglophone mob stormed the stately parliament building and put it to the torch. The attack resembled the insurrection at the United States Capitol last year, only worse — far worse.

Gone was the cradle of Canada’s infant democracy. Gone was the twentytwo- thousand-volume parliamentary library with its irreplaceable books, archives, and art. And gone was Montreal’s role as capital city. Henceforth Parliament would migrate between Toronto and Quebec City, until Queen Victoria made Ottawa the permanent capital.

For a century and a half, the remains of the first Parliament of Canada lay buried and forgotten beneath what is now Place d’Youville, only a stone’s throw from Montreal’s bustling harbour. In 1920 the site became a parking lot. Seventy years later a planned underground parking garage threatened to make the loss permanent. Happily, Montreal commissioned studies that revealed the site’s unexpectedly rich historical significance, and cars had to park elsewhere.

In 2010 the Pointe-à-Callière Montréal Archaeology and History Complex began a huge excavation to preserve and to document the architectural remains as well as many thousands of artifacts. Under the direction of chief curator and archaeologist Louise Pothier, Pointe-à-Callière has published its findings in a superbly designed volume. Montréal Capital City, the English translation, contains all the full-colour maps, artworks, photos, and interpretive articles from the original French edition.

The story it tells is extraordinary. The building opened in 1834 as St. Anne’s Market, Montreal’s secondlargest structure, its neo-classical design inspired by Boston’s Quincy Market. But St. Anne’s had a strikingly original feature — it was built directly over the Little River, which emptied into the St. Lawrence nearby. The Little River was channelled into a vaulted underground canal to cool the market’s produce cellar and drain its waste water, an engineering feat that was unique at the time.

The canalized river performed a similar function when St. Anne’s was ingeniously repurposed in 1844 for the Parliament of the Province of Canada, which comprised much of today’s Quebec and Ontario. Butchers’ stalls became public servants’ offices. The upstairs halls where concerts and meetings had been held, and where the abolition of slavery in the British Empire was celebrated, were converted to chambers where parliamentarians debated..

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

The most inflammatory debate erupted in April 1849, when the Reform government of Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine planned to compensate the insurgents of the 1837 Rebellion of Lower Canada for property damage they had suffered at the hands of British troops. Scandalized English-speaking Tories claimed the bill would reward treason, benefiting Patriote rebels who had taken up arms against the Crown. Demagogues whipped up an anti-French street mob that marched on Parliament with torches and stormed into a sitting. Within hours the great structure burned to the ground.

This assault on democracy had deeper causes than a single bill. Canada was suffering from a severe economic depression that followed Britain’s adoption of free trade. Montreal’s anglophone business community felt abandoned by the mother country, and the resentment was exacerbated when Governor General Lord Elgin assented to the Rebellion Losses Bill — it was proof to angry opponents of the government of “French domination” and a cause for some to agitate for joining the United States.

This stirring narrative sags in the middle of the book, when it is interrupted by articles that are heavy on political theory and that sometimes suffer in translation.

But the pace picks up again with a return to the material and social history that the book explores so brilliantly. Archaeological and archival research combines with 3-D technology to show what the interiors of the market and parliament buildings looked like; to display recovered dinner settings, and chamber pots, and charred books; to demonstrate how women played indispensable roles as innkeepers, market vendors, charitable workers, and brothel keepers; and to show how Innu and Anishinaabe leaders journeyed to the capital to seek justice for their peoples.

The book leads to an ironic realization: If anglophone Montrealers hadn’t destroyed a great building that had been largely their own creation, Montreal might still be the nation’s capital today — and our political evolution would look very different indeed.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Our online store carries a variety of popular gifts for the history lover or Canadiana enthusiast in your life, including silk ties, dress socks, warm mitts and more!