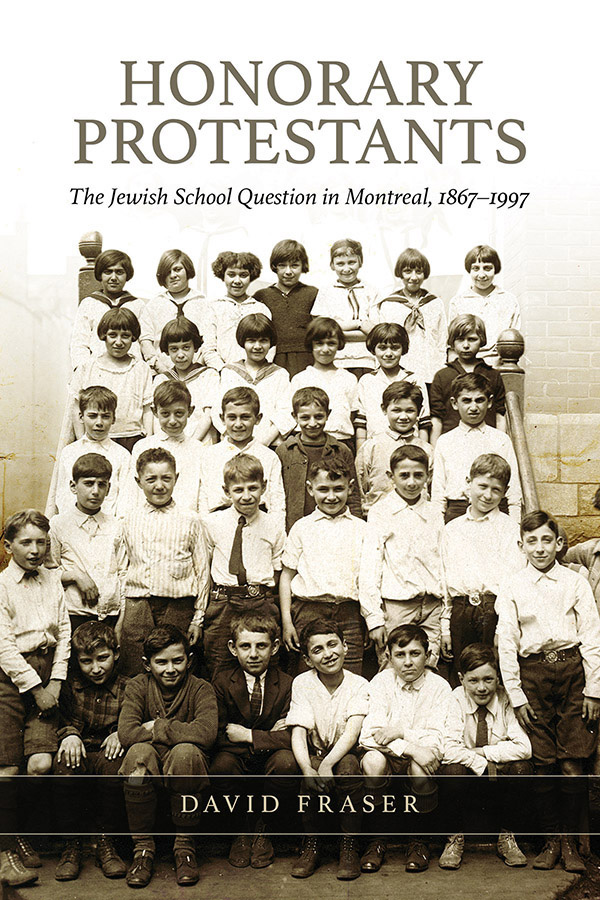

Honorary Protestants

Honorary Protestants: The Jewish School Question in Montreal

by David Fraser

University of Toronto Press

529 pages, $85

Are Jewish students Catholics? Are they Protestants? Or what are they? For nearly 150 years, the “Jewish school question” troubled Quebec’s education system. How this was managed through social, legal, and political compromises, within a context of some intolerance and inequality, is the central theme of the fascinating book “Honorary Protestants.”

David Fraser, a Canadian-trained law professor at the University of Nottingham, has written a detailed study on the evolution of Quebec’s faith-based schools that were so important to the life of Montreal’s Jewish community. These arrangements were a testing ground for “reasonable accommodation” and created an early form of Canadian multicultural policy.

The story begins in the 1840s, when Quebec (then Canada East) established local school boards along religious lines. Catholic education was effectively under Church control while Protestant schools, although more diverse in their denominations, were also faith-led.

The faith-based system in Quebec and the other British North American colonies was meant to be protected by Section 93 of the 1867 British North America Act. This undertaking was central to the Confederation pact. Neither of the dominant Christian religions would be able impose its schooling and values on the other — it was a great Canadian solution.

Subsequent education decisions (notably in New Brunswick in 1870, Manitoba in 1890, and Ontario in 1912) moved Canada away from Confederation’s spirit of compromise. Judges interpreted the BNA Act in its barest legalist bones, while politicians were hardly concerned with local minorities as they reduced (or eliminated) both Catholic and French-language public schooling.

Quebec was the exception. Its balance of Protestants and Catholics, English speakers and French, ensured that the BNA Act’s protection for minority education would remain functional and effective.

Fraser examines the impacts in Quebec after the arrival of many Jewish immigrants from Europe. Which denominational school system would accept these new “foreign” immigrants? How would Jewish property owners be taxed? How would Christian values still be taught within existing schools? And could Jewish students receive their own cultural and religious education within a public system?

Early compromises and half measures reflected prejudices that were both common and continuing. At different times, Jews were administered as if they were Catholics. Then they were Protestants. Sometimes they were barely tolerated, but at other times they were welcomed. Hence Fraser’s intriguing book title: “Honorary Protestants”. Local school boards faced political, legal, and moral challenges. There were conflicts about how to respond to Jewish community leaders who wanted civic education with a strong sense of loyalty to British-style institutions. There were conflicts, as well, between different viewpoints and congregations within the Jewish community.

Christian leaders — sometimes Catholics but mainly Protestants — supported their own faiths but also created accommodations that went beyond the provisions of Canada’s and Quebec’s laws. These compromises were not perfect, but they worked and were modified over time. In Fraser’s scholarly words, “solutions to these competing rights claims often exceeded or went outside the strict parameter of positive legality.

”

This very thorough study concludes with the 1997 constitutional amendment that replaced Quebec’s denominational boards with a language-based education system.

Fraser’s underlying thesis is that tenacity and compromise, as much as legal formulas and court judgments, are essential for public policies promoting tolerance.

Reading his book, I remembered my own years in a Montreal Protestant school where, with thousands of other Jews, I recited the Lord’s Prayer, read from the Bible, but also received time off for our religious holidays. Quebec’s style of pragmatic accommodation, had it prevailed historically in Manitoba, New Brunswick, and Ontario, could have led those provinces to avoid damaging injustices to French-language education — and consequent difficulties for this country.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement