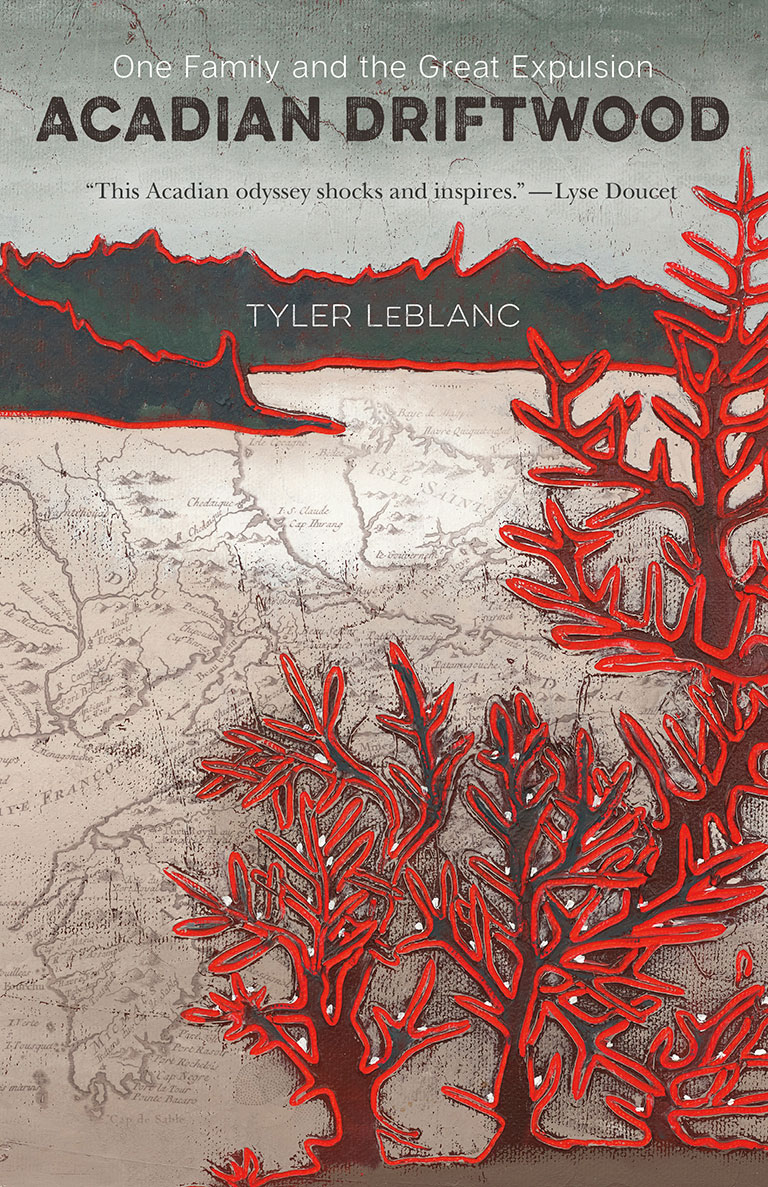

Acadian Driftwood

Acadian Driftwood: One Family and the Great Expulsion

by Tyler LeBlanc

Goose Lane,

183 pages, $19.95

A double review with

Menno Moto: A Journey across the Americas in Search of my Mennonite Identity

by Cameron Dueck

Biblioasis,

320 pages, $22.95

Tyler LeBlanc didn’t care much about history until he stumbled upon a family secret hiding almost in plain sight. He’d always believed, as family lore had maintained, that LeBlanc was an adopted surname. Instead, after being prodded to explore further, he found that a suppressed lineage could be traced back seven generations to one of the original settlers of Acadia.

The Acadians were a French-descended people who resided in and around present-day Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island beginning with the founding of Port-Royal in 1605. Forgotten by the French, they formed their own identity, intermingling with their friends and allies the Mi’kmaq. But, as conflicts between the British and French developed, their political situation grew increasingly precarious.

When British administrators conceived a plan in 1755 to round up the more than fourteen thousand Acadians and to remove them from their homes, some scattered and assimilated into nearby areas. Most, however, were forced onto ships where they were held, often for long periods, before being deported to various colonies around the Atlantic.

Much has been written about the great expulsion and the worldwide impact of the 1756–63 Seven Years War that resulted in France’s surrender of almost all of its remaining North American colonies to Britain. In his book Acadian Driftwood, LeBlanc focuses on ten ordinary Acadians: his great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather Joseph LeBlanc and many of the latter’s siblings. He quotes author Erik Larson: “It is one thing to write Great Man history, quite another to explore the lives of history’s little men” — and women, I must add.

LeBlanc, a self-professed non-historian, dedicates separate chapters to the brothers and sisters who suffered through the hardships that came with exile and homelessness — and that were compounded by the loss of their culture and family support systems.

Acadian Driftwood is a unique family genealogy that draws upon the oral testimony of Joseph LeBlanc’s brother Jean Baptiste to tell the moving stories of people who, author Tyler LeBlanc writes, “represent the displacement suffered at large for the entire Acadian population during Expulsion.”

Unlike LeBlanc, but like many North American “Mennos,” Cameron Dueck was always aware of his family history and, by extension, of the Mennonite story — which involves fleeing persecution by various Roman Catholic and Protestant states after the Mennonites originated in the sixteenth century as an Anabaptist Christian sect in the northern Netherlands. Many of them landed in Canada and in other parts of the Americas, including some who then left Canada due to pressures to assimilate. Dueck was interested in tracking the historical migrations and diaspora of “his people” (although not his direct ancestors), and he did so quite literally — with a motorcycle trip through the Americas.

Dueck, who now lives in Hong Kong, is an adventurer and a journalist with impressive credentials and Mennonite roots in Manitoba. He starts with an admittedly ambiguous relationship towards his ancestry, and his months-long tour visiting the Mennonite diaspora is a journey of discovery that’s both eye-opening and troubling.

Parts of his book Menno Moto are delightful. The story of Klaus and Greta, a more progressive couple who are part of the Manitoba Colony in Belize, is lively and informative. Dueck provides historical details while painting a vivid picture of colony life — including about young colony members who have become involved with drug cartels. Dueck’s perceptiveness and his capacity for deeply connecting with the people he meets underpin his ability to capture the variety of Mennonite life, demonstrating it as anything but homogeneous.

His visit to the Mennonite colonies in Bolivia — “among the most socially conservative” — marks a low point. He meets with various community members, including the imprisoned alleged perpetrators, about the notorious “ghost rapes” of vulnerable community members that hit the news a decade ago. The depth, consideration, and intelligence of Dueck’s treatment of this complex situation is nothing less than astonishing; it expands the quality of Mennonite literature beyond the approaches typical of writers who seem too intent on moralizing or hectoring.

In seeking “what it means to be Mennonite,” and on his arduous journey that involves a personal quest for identity, with all the ambivalence that entails, Dueck at times seems to miss the bigger picture — when the cost of identity is so dear for historically persecuted or discriminated-against communities. “In the end, we all pick and choose,” he writes, “whether we want to keep the buggy or buy a car, choose an English name or use our Chinese one. Language, faith, family, tradition. As soon as we expose ourselves to any foreign culture ... we have to start choosing.”

But history and culture, however we understand their relation to our daily, lived experiences, are also shaping and constraining forces. And, more for some people than for others, it’s not as simple as picking and choosing. The frame of culture makes history real and poignant, and larger than just what we make of it in our minds. It’s also what makes Dueck’s book so affecting: This history-as-adventure tale is authentic, funny, insightful, incredibly tender, at times heart-wrenching — and imminently readable.

Despite a few hasty attempts to distill some nugget of wisdom from mere anecdote or experience, Dueck is a gifted writer with such compassion for the culture, and such profound intuition for its tone, that he tells the stories of the Mennonites he meets with fitting gravitas, insight, and deep heart, as well as a good deal of humour and pathos.

Descriptions and dialogue sing. But it’s the discreetly rich moments — the “muffled sounds of sleeping farms” in the night, with bright constellations overhead; the Old Colony girls in Remecó, Patagonia, at the very end of the book, giggling quietly during Sunday meddach’schlop (after-lunch nap) about the “stranger” or weltmensch (world-person) whom they “guess he’s a Mennonite” — that, in their ability to hold the tension between the great span of the past and the narrow pinprick of the present, take your breath away.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement