Shed No Tear

The last time Canada’s team won gold at the International Ice Hockey Federation World Junior Championship, the foot-stomping Halifax crowd greeted each goal with the rollicking chant, “Heave away, me jollies, heave away!” The traditional sea shanty by Newfoundland band the Fables was chosen as Team Canada’s goal tune for the 2023 tournament and proved wildly popular. The phenomenon reflected a worldwide resurgence of humble seafaring songs — and Canada’s role in keeping them alive.

The COVID-19 pandemic likely contributed to the craze. As people were sequestered in their homes, songs of adventure on the high seas sung in unison offered a glimpse of hope and community.

Sea shanties (or chanties) originated as songs to accompany rhythmic labour on ships and boats. Other sea songs, such as ballads, express shared emotion, especially grief, according to Heather Sparling, Canada Research Chair in Musical Traditions and a professor of ethnomusicology at Cape Breton University. Her research focuses on songs about disasters, especially shipwrecks.

In maritime communities, ships sometimes go missing without a trace. “It would take a while for people to realize that something had gone wrong,” she said. “You can’t go to the place where the ship went down and lay a flower…. Writing [songs] becomes one possible way of, sort of, processing that grief.”

The tradition continues today. After five young fishermen perished in a storm off the coast of southwestern Nova Scotia in 2013, Sparling found at least eleven songs written about the tragedy.

Shanties and ballads have retained an audience in Canada, in part because of the East Coast’s vibrant folk-music scene. The genre also contributes to a distinct Canadian identity: Think of the late Stan Rogers’ 1976 hit “Barrett’s Privateers.” This rousing anthem tells the story of a jaded sailor on the “scummiest vessel I’ve ever seen” who loses his legs after a skirmish with a better-equipped American warship in 1778.

Mike Magee, who works in marketing for Montreal independent record label Stomp Records, said “Barrett’s Privateers” and other Rogers tunes were fixtures of his upbringing: “It wasn’t unusual to be out at a pub, diner, or a hockey game and have a round of ‘Barrett’s Privateers’ or ‘Northwest Passage’ spontaneously erupt.” Magee said some of the artists he represents, such as the folk-punk party group the Dreadnoughts and Celtic punk rockers the Real McKenzies, both based in Vancouver, have carried this influence into the contemporary music scene. “We’re very lucky to have a few excellent bands who have carried the torch to keep the tradition alive.”

Few Canadians are better-versed in shanties than Seán Dagher. The Montreal-based musician hosts a YouTube series called The Shanty of the Week, in which he explains the origins of different shanties. It turns out that the shanty genre is not inherently Canadian any more than it is American, British, or Australian.

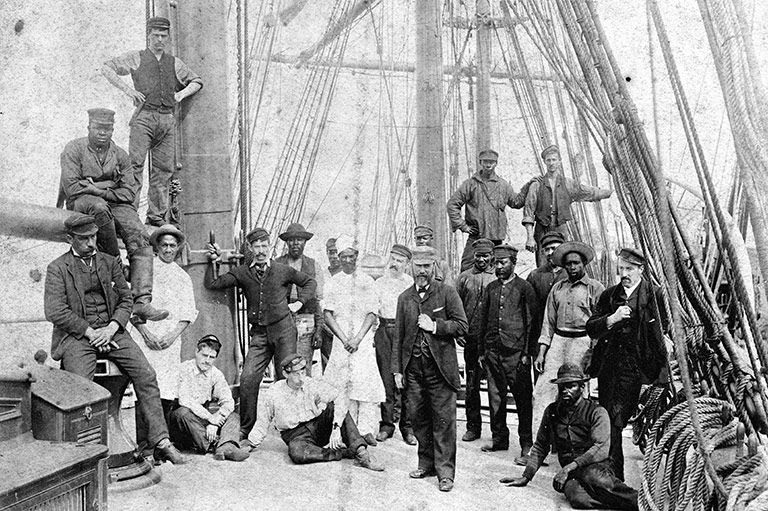

“They come from everywhere,” said Dagher. “You can classify the songs by the language, but you can’t say that this song is American, or this song is English, because the songs went where the sailors went.”

Some scholars believe shanties originated in the American South in the early 1800s. “Shantying basically starts in the cotton industry,” said University of Kentucky associate professor of ethnomusicology James Revell Carr. “The earliest songs in this repertoire were sung initially by Black stevedores, people who were loading cotton onto ships.”

The dock workers were likely drawing inspiration from a pre-existing genre of Black slave work songs, he said. Singing made hard work easier, and the songs quickly spread throughout the maritime trade routes of the world, including to the whaling ships of the North.

Whatever the origins of sea shanties, Dagher believes Canadians have played a vital role in keeping them alive. For example, he said, the modern version of the shanty “Randy Dandy O” — which recounts the preparations of sailors heading for Cape Horn — was arranged in Nova Scotia before being covered by artists such as the Dreadnoughts and Bristol, U.K., folk group the Longest Johns.

The sea shanty tradition has now become an undeniable part of Canadian culture, said Dagher. “I think the Maritimes and Newfoundland are a sort of portal where many Canadians say, ‘Well, this is part of Canada, [so] I am allowed to feel that this is a little bit my music.’”

More from Jonah Grignon

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!