Painters Eleven: Art Shock in Toronto

In October 1953, when he organized the Abstracts at Home exhibition, William Ronald was just twenty-seven. Young, talented, bohemian, recently returned from New York, and seething with contempt for Toronto’s conservatism, Ronald gathered six like-minded painters and staged an artistic revolt that began, not in a manifesto blazing with rage against the state, but in the furniture department at Simpson’s.

Article continues below...

-

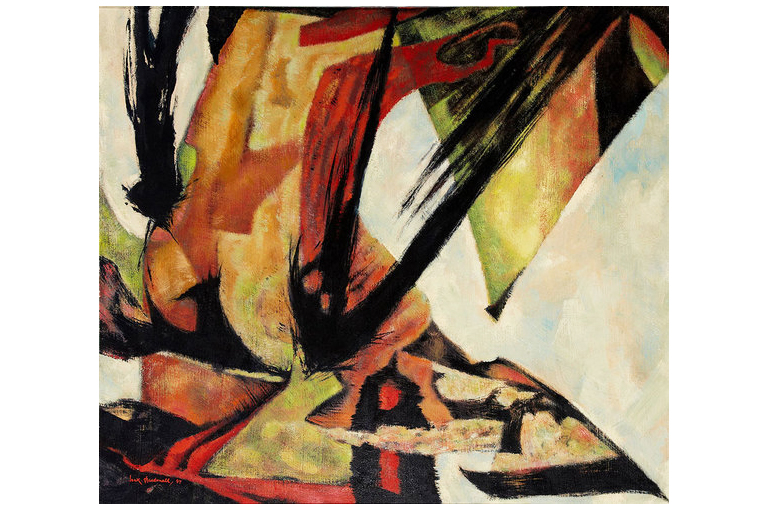

Growing Form (1953). Had he lived, Oscar Cahén might be remembered as the greatest of all Canadian artists. A gifted illustrator, he also produced some of the group's most profound works, remarkable for their freedom of movement and striking colours. He remained the artistic center of gravity in Painters Eleven even after his death in a car accident in 1956.RBC Corporate Art Collection © The CAHÉN Archives

Growing Form (1953). Had he lived, Oscar Cahén might be remembered as the greatest of all Canadian artists. A gifted illustrator, he also produced some of the group's most profound works, remarkable for their freedom of movement and striking colours. He remained the artistic center of gravity in Painters Eleven even after his death in a car accident in 1956.RBC Corporate Art Collection © The CAHÉN Archives -

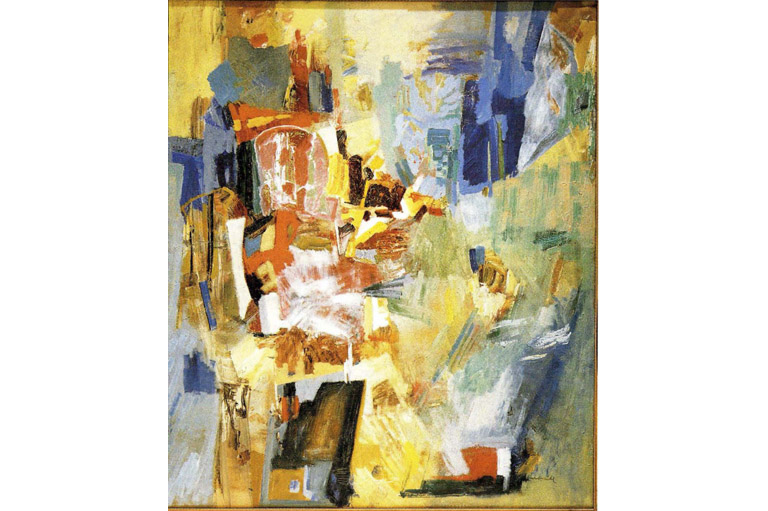

Iridescent Monarch (1957). "Nonobjective" is how some abstractionists described their work, meaning that their paintings represented no object in the visible world. Instead they used colour and form to express intangibles like emotions, ideas, and imagination. For Jock Macdonald, an instructor at the Ontario College of Art, life was a progress towards understanding the spiritual laws that he believed governed the universe, and abstraction was his means of exploring them.Art Gallery of Hamilton | Gift of the Canada Council, 1960

Iridescent Monarch (1957). "Nonobjective" is how some abstractionists described their work, meaning that their paintings represented no object in the visible world. Instead they used colour and form to express intangibles like emotions, ideas, and imagination. For Jock Macdonald, an instructor at the Ontario College of Art, life was a progress towards understanding the spiritual laws that he believed governed the universe, and abstraction was his means of exploring them.Art Gallery of Hamilton | Gift of the Canada Council, 1960 -

At her best, as in Symphony (1957), Alexandra Luke (1901-1967) was a great painter, capable of conceiving of her work on a huge scale (the piece is more than seven feet tall). She was also well connected: her husband was the son of the founder of General Motors of Canada. Symphony shows the close play of brightly coloured rectangles that is characteristic of the style of Hans Hofmann, the European émigré under whom several members of Painters Eleven studied.Collection of The Robert McLaughlin Gallery / Photo: Thomas Moore

At her best, as in Symphony (1957), Alexandra Luke (1901-1967) was a great painter, capable of conceiving of her work on a huge scale (the piece is more than seven feet tall). She was also well connected: her husband was the son of the founder of General Motors of Canada. Symphony shows the close play of brightly coloured rectangles that is characteristic of the style of Hans Hofmann, the European émigré under whom several members of Painters Eleven studied.Collection of The Robert McLaughlin Gallery / Photo: Thomas Moore

Ronald persuaded management at the venerable Yonge Street department store (where he had worked as a window designer) that abstract art could blend harmoniously with more traditional furniture, enlivening the sales of both. To some future critics it would seem unforgivably bourgeois, especially compared to the cultural declaration of war called Refus global that marked the arrival of modern art in Quebec, but Ronald was motivated as much by the desire to plant the modernist banner in English Canadian soil as by the prospect of commercial success.

In 1953 Toronto seemed the unlikeliest place for such an exhibition. Visitors found the city dour and churchy. Sidewalk cafes were prohibited, and it was illegal to sell tobacco on Sundays. Even its former mayor, Allan Lamport, conceded that the city was dull after dark, a state of affairs pleasing to the novelist Morley Callaghan, who appreciated the lack of distractions imposed upon him by the “orderly, unexciting, strict Toronto life.” For years the city’s artists had wrestled with ennui like depressives. Just two commercial galleries sustained them as they laboured under the thrall of the Group of Seven, willfully insulated from external influences. A gloomy 1950 article in Canadian Art concluded: “There is something rotten in the state of Toronto art, and it is of the dead rot kind,” or, as the artist Graham Coughtry put it, “every damn tree in the country has been painted.”

Beneath the pallid surface, however, a few modernist pioneers, including Bertram Brooker and Lawren Harris (formerly of the Group of Seven) had laid the groundwork for Ronald’s revolt. Winnipeg’s Brooker had mounted an exhibition of abstracts at the University of Toronto as early as 1931, and Harris had broken decisively from the mode of painting he helped to create with a series of geometrical abstractions he began in the late 1930s. While these works helped to acculturate Torontonians to the artistic renaissance underway in Europe and the United States, it is also true that in retrospect they seem tentative and sometimes timid, especially compared to the style emerging from New York called “abstract expressionism.”

Easier to point to than to define, abstract expressionism was big, bold, impetuous, and radically abstract, a style that captured the beat and tempo of New York life. Ronald and the artists he gathered for Abstracts at Home—Jack Bush, Ray Mead, Tom Hodgson, Kazuo Nakamura, Oscar Cahén, and Alexandra Luke—admired and sought to emulate the spirit, if not always the precise technique, of the New York school, rather than that of their Canadian forebears. Some of them had encountered abstract expressionism in American galleries or in occasional exhibitions of contemporary art at the Art Gallery of Toronto. Luke and Ronald had even studied in Massachusetts and New York under Hans Hofmann, a gifted European émigré who taught a generation of painters the artistic and verbal vocabulary of modernism.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

At Simpson’s in 1953 this vocabulary was unveiled full-force upon Toronto. Not many paintings sold, but Ronald’s group judged the exhibit successful enough to warrant furthering their association. In November they met again at Alexandra Luke’s cottage near Oshawa, their number now grown to eleven. Ronald brought his mentor from the Ontario College of Arts, Jock Macdonald. Oscar Cahén invited his friends Harold Town and Walter Yarwood, and Ray Mead brought Hortense Gordon, an art teacher from Hamilton who had also studied under Hans Hofmann. To date, most of their opportunities to show abstractions had come though juried exhibitions with the official societies, where hostile organizers usually relegated modern art to back rooms and corners. “We were sick,” Town said, “of being told where to hang, how to hang, and when to hang,” and they reasoned that they had a better chance of being seen collectively than as individuals.

At Town’s suggestion, they adopted the name Painters Eleven. Jack Bush had representation at the prestigious Roberts Gallery, and he secured an exhibition for them there in February 1954. It was the first show of its kind in a commercial gallery in Toronto. Years later Ray Mead recalled, “we thought they’d open the doors like they do for a matinee and everyone would come pouring in,” but when the doors opened at six o’clock, nobody did. Town finally coaxed some strangers from the street in for a drink. Gradually people began to arrive, sensing, perhaps, that something important was happening, even if they weren’t certain what it was. By the time the show closed two weeks later, it had drawn the biggest crowds the Roberts Gallery had ever seen.

Not everyone agrees that any works sold, and it seems somehow more appropriate to believe that none did. Reviewers were positive but somewhat baffled, and audiences at early abstract shows tended to think that the paintings were like a Rorschach test, where the goal was to find recognizable forms on the canvas. With some modern art this was possible. Cubism and surrealism abstracted from nature, but abstract expressionism typically made no reference to the outside world; it was the triumph of the formal qualities of painting over figurative content, the act of painting as its own subject. In this sense it was like improvisational jazz—Charlie Parker’s bebop or Ella Fitzgerald’s scat singing—not random noise, but spontaneity guided by talent.

While the Group of Seven possessed a distinctive style, Painters Eleven never sought aesthetic common ground beyond a commitment to modernism. Abstract expressionism serves as convenient shorthand to describe their style, but their work could include aspects of cubism, surrealism, and automatism as well. Not all of their canvases were totally abstract (Nakamura, for instance, was fond of modernistic landscapes) and only a few worked like the New York “action painters”—squeezing, pouring, and scooping paint around in a frenzy—but their paintings on the whole were freer, more daring, and more abstract than anything Canadians had seen yet. Town, who wrote their exhibition catalogues, called their approach “harmonious disagreement.”

Harmony did not reign at their meetings. A generation gap between the members was evident from the outset: the young men at the core of the group were in their twenties and thirties. Bush, Luke, and Macdonald were in their forties and fifties, and Hortense Gordon was nearly seventy. They had no formal leader or structure, arrived at decisions democratically, and the younger members were capable of arguing long into the night amidst too much alcohol and too much ego. “It was nothing to see two guys end up on the floor in a fistfight,” Ronald recalled years later.

For the next six years Painters Eleven exhibited regularly in Toronto and throughout Ontario. But like most of the eleven, Ronald found his artistic moorings in New York rather than in Toronto. He moved there late in 1954, and eventually obtained representation at the Samuel Kootz Gallery, where Hans Hofmann and Robert Motherwell showed their work. With his New York contacts, Ronald arranged for Painters Eleven to exhibit alongside the American Abstract Artists at their twentieth anniversary exhibition at the Riverside Gallery in April of 1956. It was a singular opportunity. New York had long inspired them, and they were eager to test their mettle in what had become the world centre of the avant-garde.

In the event the reviews were mostly positive. The most enthusiastic endorsement came from Lawrence Campbell, a critic for the prestigious Art News:

I think the Americans who saw the exhibitions today were surprised to find that the level of Canadian painting was comparable to American painting, as inventive, and if anything freer, more creative, and less self-conscious compared to works by the members of the American Abstract Artists.

Not all of New York’s critics were so enthusiastic, but they did not, at least, question the right of abstract art to exist. Canadian critics frequently did. Back home, criticism of modern art was never more vocal. Kenneth Forbes, a well-known portrait painter who had resigned from the Ontario Society of Artists when abstracts were admitted to its 1951 exhibition, led the traditionalist opposition. His remonstrations against modernity were widely printed. In 1956, when the National Gallery paid $50,000 for Picasso’s The Small Table, Forbes complained in the Toronto Star that the gallery’s staff was incompetent and predicted that Picassos would one day be “worth about five cents.”

To Forbes, every phase in the evolution of modern art, from Van Gogh’s “clumsy, rotten junk” to abstraction’s “vague gropings of the primitive man” had constituted nothing less than an assault on civilization. Abstract art was an oxymoron: since the purpose of art was to portray reality as such, abstraction was by definition not art. “Ugly, distorted, sadistic, grotesque, and just plain incompetent,” he wrote in Macleans, “modernistic painting is the greatest hoax in the history of human art.” Never one to back down from a verbal challenge, Harold Town fired back: “I am glad to hear from Kenneth Forbes. I thought he was dead, but had only his painting to go by.”

But Forbes was only the most militant of the antimodernists. In 1955, the Toronto Star’s art critic was left aghast by what he called an abstract “horror show” at the CNE. Toronto’s mayor, Nathan Phillips, stormed through a modernist exhibition at the University of Toronto that year, demanding the removal of several pictures because he thought that they might be obscene. Abstracts (including prize winners by Town and Cahén) in a November 1955 juried exhibition in Winnipeg reportedly left one of the organizers, the wife of the dean of the art school at the University of Manitoba, “physically nauseated,” and a letter writer in Canadian Art may have surmised what all the critics were really thinking: abstract artists “paint as though they were communists.”

However, the most piquant criticism came from cultural nationalists, who wondered why, when so many Canadian artists had striven so hard to forge a uniquely Canadian identity, abstract artists were so eager to look to the United States for inspiration and approval. Ronald and most of the eleven believed that art transcended such parochial concerns, but as he grew weary of abstract expressionism after the Riverside exhibit, Harold Town found himself more and more in agreement with the nationalists. In 1957, when Jock Macdonald invited the enormously influential American art critic Clement Greenberg to Toronto, Town joined Walter Yarwood in refusing to meet him.

Clement Greenberg was an anti-Forbes, a dogmatic apostle of the avant-garde as the only defense against the degraded products of mass culture, and when he came to Toronto in June 1957 he was near the peak of influence. Greenberg spent half a day with each of the members willing to meet him. He considered Hodgson “exceedingly good” and Mead and Macdonald ready for any gallery in New York—high praise for Canadians who measured themselves by such standards. For Jock Macdonald, a pioneer of Canadian abstraction who had endured decades of ridicule, Greenberg’s praise seemed like vindication. But the critic’s most important association was with Jack Bush, who was set to become the most famous Canadian painter of his generation. It was the beginning of a friendship that endured until Bush’s death twenty years later. Greenberg encouraged Bush to continue in the direction that he was already heading: towards the purely formal colour-field painting that Greenberg was beginning to favour.

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!

Stylistic differences between abstract expressionist painters tended to be personal rather than regional, and apart from the size of the paintings (materials were much more expensive in Canada and hence the paintings tended to be smaller), not much distinguished Canadian from American abstraction. Surprisingly, this was the one thing Greenberg found objectionable about Painters Eleven. He believed that they should use their comparative isolation from the United States to their advantage, and he encouraged them to look inward rather than towards New York for inspiration. “You can all paint excellently,” he told them. “What you have to do is realize that within yourselves you have the personal abilities to say something as profound as anywhere in the world.”

It is difficult to assess Greenberg’s impact on Painters Eleven, but there is no denying that their best and most creative work was produced in the three years that followed. But his visit also served to further divide a group that was already in the process of coming apart. Oscar Cahén had been killed in a car accident in November 1956. In a group of great talents, he had stood out as exceptional, and his loss was deeply felt. Ronald resigned from Painters Eleven in 1957, citing the expense of living in New York but showing in Toronto, and Ray Mead’s advertising agency transferred him to Montreal early in 1958, effectively cutting him off their meetings.

Moreover, by 1959 most of the others felt their association had served its original purpose. No longer were they artistic outcasts. Unlike their French-Canadian predecessors, Les Automatistes, who had sought nothing less than social revolution, Painters Eleven had sought only a united front against artistic traditionalism. Traditionalists still howled, but by their continual presence, Painters Eleven had changed Toronto’s art scene. Writer Robert Fulford recalls how, at age twenty-two, he left Painters Eleven’s first exhibition “with a sense of new life in Canadian art.” Young artists Dennis Burton and Gordon Raynor converted to abstraction immediately after seeing a Painters Eleven exhibition in 1955.

The magazine Canadian Art had begun the decade with a lament for Toronto’s better days, but by its end spoke metaphorically of a city that had undergone a “blood transfusion,” with an unprecedented “quantity and variety of art.” Harold Town and William Ronald had earned international reputations, and Jack Bush was about to. Jock Macdonald, considered an eccentric in 1950, had become the most popular instructor at the Ontario College of Art. In this new artistic climate, there seemed little point in carrying on. Painters Eleven voted to disband in October 1960.

In 1954 Painters Eleven seemed to be at the vanguard of a revolution in art, when in fact they were equally at its end. In New York the days of the paint-splattered bohemians were already passing, and Painters Eleven led Toronto’s first and last great abstract-expressionist movement. Some of the best Canadian artists of the sixties elaborated upon the Eleven’s style, but many others were inspired by their rejection of, rather than their admiration for, Painters Eleven’s work. Artists like London’s Greg Curnoe broke from abstract expressionism not because they shared the views of traditionalists like Forbes, but because they believed abstraction was elitist, divorced from the day-to-day reality of life, and above all, another example of American cultural imperialism.

In one of their earliest exhibition catalogues, Town wrote that the Painters Eleven had a “profound regard for the consequences of our complete freedom.” One unforeseen consequence of the “complete freedom” they endowed on Toronto’s art scene was that it would one day be vibrant enough to leave them behind.

Et cetera

The Theatre of the Self: The Life and Art of William Ronald by Robert Belton. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, Calgary, 1999.

The Canadian Painters Eleven by Ross Fox. The Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa, 1993.

The Crisis of Abstraction in Canada: The 1950s by Denise Leclerc. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 1993.

Canadian Art in the Twentieth Century by Joan Murray. Dundurn Press, Toronto, 1999.

Why A Painting Is Like a Pizza: A Guide to Understanding and Enjoying Modern Art by Nancy G. Heller. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1999.

Read more about influential midcentury art critic Clement Greenberg.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement