Beer Wars

-

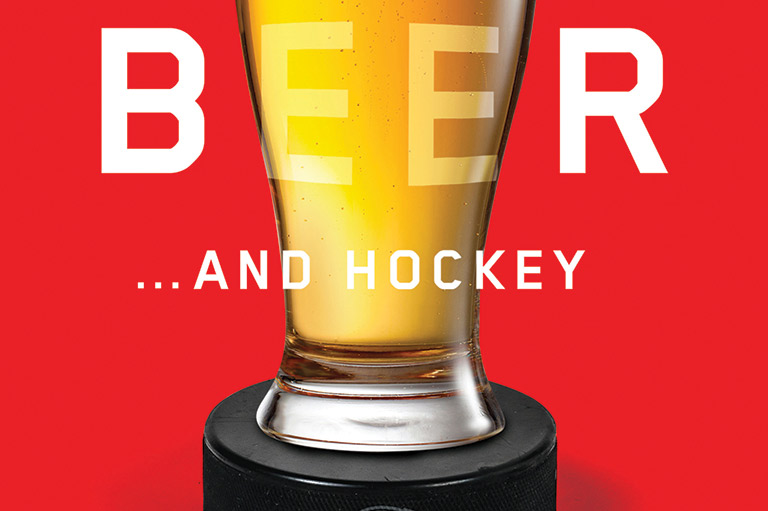

Woman's Holy War, a lithograph by Currier & Ives, depicting women of the Temperance League destroying barrels of alcohol.Illustration digitally altered by Michel Groleau with the permission of Corbis

Woman's Holy War, a lithograph by Currier & Ives, depicting women of the Temperance League destroying barrels of alcohol.Illustration digitally altered by Michel Groleau with the permission of Corbis -

The Sleeman family’s Silver Creek Brewery in Guelph, Ontario.Sleeman Brewery

The Sleeman family’s Silver Creek Brewery in Guelph, Ontario.Sleeman Brewery -

Brewer John Carling.McCord Museum

Brewer John Carling.McCord Museum -

A man is arrested in Toronto in September 1916 for violating prohibition.Canadian Press

A man is arrested in Toronto in September 1916 for violating prohibition.Canadian Press -

An ad from Boswell’s, a now defunct Quebec brewery that was established on the same site as Jean Talon’s La Brasserie du Roy.Collection of Nicolas Bourgeault

An ad from Boswell’s, a now defunct Quebec brewery that was established on the same site as Jean Talon’s La Brasserie du Roy.Collection of Nicolas Bourgeault -

A 1916 prohibition parade in Toronto.Canadian Press

A 1916 prohibition parade in Toronto.Canadian Press

On June 17, 1918, Konrad Knapp sat down at his makeshift desk in a half-lit corner of his brewery. From the desk’s only drawer he pulled a piece of paper and began to write to his sister. He Had often done this over the years, informing her of family matters and the state of his business. The Calgary-based Mountain Springs Brewery had been a growing concern in the West since the 1890s. But the tone of this letter was more solemn than those he had written in the past. “I am no longer able to continue,” Knapp wrote. “The prohibitionists are causing me to lose my business.”

During the first decades of the twentieth century, one province after another went “dry.” In March 1918 the federal government added to the brewers’ plight by making it illegal to manufacture “intoxicating” drinks. Four months later, Knapp put all the assets of his brewery up for sale and got out of brewing for good.

Knapp was not the only brewer to be affected by the apostles of teetotalism and their war on beer. Between 1878 and 1928 the number of breweries was cut by almost three quarters. Some of Canada’s most venerable brewers were driven out of business as a consequence of numerous attempts by government to stop the selling, and ultimately, drinking, of alcohol. Sleeman Brewing and Malting Company, for example, was forced to turn off its taps in 1933 after eighty-six years in the brewing business. It wasn’t until 1988 that John Sleeman, who was named after his great-great-grandfather and founder, revived the family business. Likewise, Carling Brewery was unable to operate under the constraints of Prohibition and was sold to the rum-running syndicate of Windsor, Ontario-based Low, Leon and Burns. The Carling brand went through several more ownership changes and is currently owned by Molson Coors Brewing Company.

Bottom feeders like Edward Plunkett Taylor—later dubbed Excess Profits Taylor by his critics—used the opportunity of Prohibition to capture assets at rock-bottom prices and to construct large breweries that could capitalize on modern production techniques and advertising. By 1935, Taylor’s company, Canadian Breweries, was twenty times the size of most turn-of-the-century breweries and represented a new post-Prohibition reality.

Gone were the days of small breweries producing distinctive beers for a local market. Gone also were the fortunes of many Canadian brewers. Legacies were lost; thousands of well-paying jobs disappeared; and the civil liberties of thirsty Canadians were restricted. Yet all this might all have been avoided had the brewers waged a better war against the prohibitionists.

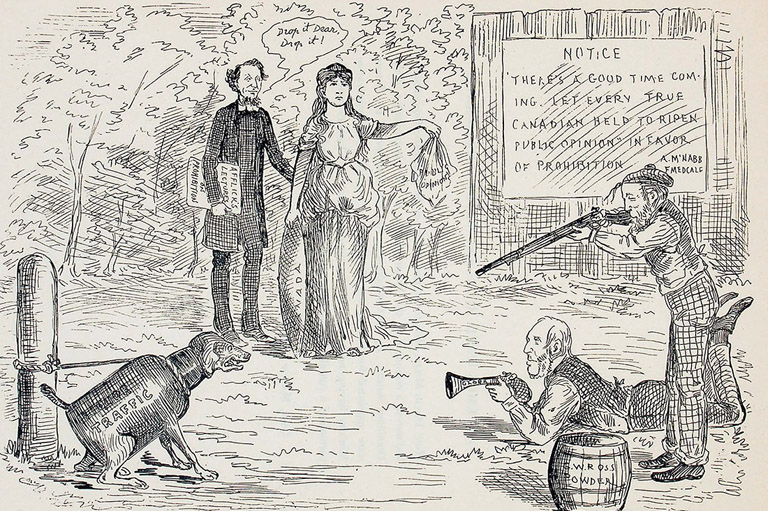

In the early nineteenth century a religious awakening swept the land. Drunkenness was specifically singled out as a great sin. Canada at this time was awash in alcohol. When the English temperance advocate J.S. Buckingham visited in the 1840s, he was repulsed by the level of public intoxication. “From all the opportunities I had of judging,” he scornfully wrote, “the people of Upper Canada are less temperate than the people of the United States. Absolute drunkenness abounds. …”

If Buckingham had travelled to Kingston he might well have bumped into the future prime minister of Canada, John A. Macdonald, stumbling out of the local tavern, a stiff drink still in his hand, chanting his favourite ditty: “A drunk man is a terrible curse / But a drunken woman is twice as worse.”

Only Macdonald’s tall stature would have distinguished him. Most Canadians drank during the nineteenth century—men, women, and children. They drank at home, at work, at dances, at building bees, and during elections. They drank in taverns, hotels, marketplaces, factories, hospitals, and even churches. The Upper Canadian census of 1851 recorded 1,999 taverns, or one to every 478 people. Toronto had more taverns than streets. Troubles related to the high level of alcohol consumption combined with the religious awakening to give rise to the Canadian temperance movement. Early feminists were also strong supporters of Prohibition, since drinking fuelled domestic violence.

At first, the movement was not necessarily against beer. Indeed, due to its lower alcohol content, temperance advocates initially viewed beer as an ideal “temperance drink.” But gradually, many in the movement embraced the more radical position of total abstinence or teetotalism. After all, teetotallers claimed, beer did not exist in Christ’s time, and therefore, if one was to live in godly perfection, one should abstain. In fact, they were wrong. Beer goes back to pre-Christian times. And anti-prohibitionists could have countered that Christ turned water into wine. Nevertheless, Temperance leaders believed consumption of beer would inevitably lead to the use of harder alcohol. Moreover, as the prominent prohibitionist Francis Spence noted in 1875, too much beer, like too much wine or spirits, would result in drunkenness.

Spence was speaking from experience. He grew up in Toronto—with its more than a thousand grog shops in 1861—and personally witnessed the type of inebriation that caused Buckingham such concern. Thus Spence formed the Dominion Alliance for the Total Suppression of the Liquor Traffic.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

At the alliance’s inaugural convention in 1875, Spence laid out his strategy to put the “traffic” out of business. The Dominion Alliance would pressure the government to prohibit the production and consumption of booze, and simultaneously change the culture surrounding tippling. With this two-pronged approach spelled out, the alliance began lobbying Alexander Mackenzie’s Liberal government for dry legislation. Unlike his predecessor, Prime Minister Mackenzie abhorred drink. Nevertheless, he felt that on this issue the people should decide. Consequently, in 1878, his government passed the Scott Act, giving local governments the right to prohibit, by popular vote, the retail sale of alcohol.

The passage of the act was the first federal legislative salvo launched in the battle over the bottle, and it came as a wake-up call for those engaged in brewing. Shortly thereafter, John Carling, the brewer-turned-Member of Parliament, wrote to a few of his brewing friends calling for collective reaction. It was a new approach for Carling. He was usually content to work alone, behind the scenes, promoting his interests and, incidentally, those of other London-Middlesex brewers.

Carling had begun brewing at the age of twenty-one when he and his brother, William, took over their father’s brewery on the bank of the Thames River in London, Ontario. During the 1850s, the brothers Carling expanded their plant to take advantage of emerging technologies and markets. The brothers decided to protect this huge investment by having John Carling enter local politics. While William felt his brother’s charisma was enough to endear him to voters, John left nothing to chance. On election day, he put the company’s liquid assets to good use lubricating the electorate. The sop did not go unnoticed.

“In a room adjoining the polling station,” wrote the editor of the Canadian Free Press, “was a barrel of beer for the refreshment of the thirsty, conspicuously branded with ‘J. Carling,’ but whether as brewer or donor, or what influence the beer may have exercised in securing the head of the poll, we do not pretend to say.” Carling won the election of 1851 and never looked back. With the support of London’s leading Conservatives, such as fellow brewer John Labatt, Carling moved smoothly from local to provincial and then federal politics.

As an MP, Carling represented London almost continuously between 1867 and 1895. The only time he was out of politics was during the Liberal years of 1874 to 1878. The latter period also saw the formation of the Dominion Alliance and the ratification of the Scott Act. Relegated to the political sidelines, Carling used the time to formulate a strategic response to the prohibitionists’ attack on beer. What he envisioned was a brewers’ equivalent to the Dominion Alliance, which would, in his words, “promote Canadian brewing and further the interests of brewers.”

In 1879, the Canadian Brewers and Maltsters’ Association (CBMA) was formed. At its first meeting, the CBMA decided to lobby for the Scott Act’s repeal. The brewing lobby had reason to be optimistic about its chances. The too moralistic, too Ontario-centric, too ideological, and far too dry Mackenzie was unable to defeat Macdonald’s Conservatives at the polls. “The glass is half full,” Carling cheerfully stated in 1879.

But on Parliament Hill there was no craving to revisit the liquor question. Even Macdonald—a man who enjoyed his drink almost as much as he did his political power—was unwilling to defend the liquor traffic. With his cabinet divided over the matter, “Old Tomorrow” recognized the advantages of inaction. Like such contemporary issues as abortion, marijuana use, and gay marriage, the prohibition of alcohol split nineteenth-century Canadians down the middle. In Quebec, support was negligible, whereas in the rural communities of English-speaking Canada support was relatively high. A man whose paramount concern was always unity, Macdonald was unwilling to take any action that might divide his party and the country.

The brewers were themselves divided. Most supported the CBMAs push to repeal the Scott Act, which allowed municipalities to prohibit the sale of alcohol. But there were some who lobbied the Senate for an exemption to the act that would allow for the sale of beer. Still others actually supported the law the way it was because it contained a loophole: nothing stopped brewers in dry municipalities from shipping their beer elsewhere.

Lacking a businesslike structure, the CBMA was unable to maintain the solidarity of brewers and rein in dissidents within the industry.

To make matters worse, while the brewers were becoming increasingly divided, the prohibitionists were becoming more united. Furthermore, the prohibitionists realized something the brewers did not: this was a cultural battle as much as a political one; a fight for the hearts and minds of Canadians, as much as for having influence in the corridors of power.

As early as 1875, Francis Spence recognized this was going to be a long war. Culture and morality would take time to change. The prohibitionists might lose battles along the way, he thought, but by changing mindsets they would ultimately win the war. Prohibitionists kept driving home the message that the liquor traffic had to go. Alcohol, they said, caused poverty, misery, crime, poor health, and insanity.

In the 1890s, prohibitionists worked to have this message heard by the most impressionable members of society. “Health Readers” began to appear in Canadian schools, filled with prohibitionist propaganda. On reading a description of the alleged effect of beer on the heart, the young reader was warned that “the heart bears this abuse as long as it can and when it stops—the beer drinker is dead.”

The brewers counterattacked with ads that promised better health with beer. “Good health will be yours if you drink O’Keefe’s Bold Label Ale,” one advertisement read. “Not only a drink that refreshes,” read another, promoting Vancouver Breweries’ Cascade beer, “but one that tones up the system, builds body strength and brain efficiency.” Carling’s beer was advertised as “highly recommended by the medical community.”

Yet it seemed even the brewers themselves didn’t completely believe their own claims. Were they being worn down by the prohibitionist rhetoric? In the twilight of his career, John Carling spent much of his time lobbying for government funds to build an insane asylum, perhaps motivated by a sense of guilt and the prohibitionist rhetoric linking alcohol consumption to insanity. The ambivalence of brewers to their own profession was further reflected during the 1892 Royal Commission on the Liquor Traffic, appointed to study the feasibility of a national prohibition law. When asked if they would give up their business if compensated, roughly half of the brewers stated they would. Some talked openly about the moral strain of operating a brewery in “temperate times.”

But the greatest strategic failing was the brewers’ unwillingness to build a broad-based coalition capable of drowning out the dry voices in society. Many would be negatively affected by Prohibition: labourers, farmers, hotel and tavern owners, barrel makers, bottlers, shippers, vintners, and distillers. Yet the brewers didn’t reach out to them.

The case was different in England. In reaction to vehement attacks by teetotallers in Victorian times, brewers and publicans joined with working-class drinkers and moderate reformers to prevent government support of anti-drink legislation. This success might have served as a model for Canadian brewers—many of whom, like Carling, were of British stock. But they took no notice.

Brewers would have found an ally in the Canadian working dass, which was overwhelmingly against the idea of full-fledged prohibition. Increasingly workers argued they had a constitutional right to drink beer. Tapping into this sentiment, labour leaders told their governments that prohibitionist legislation would force thousands out of work. Despite the strong working-class opposition, the brewing industry was unwilling to unite with labour to prevent prohibition.

Certainly the idea of cozying up to labour was somewhat lost on Konrad Knapp. In the months leading to the liquidation of Mountain Springs’ assets, Knapp wrote, “I cannot think what else I might do [to retain the business] Knapp was wont to blame himself for his firm’s failings. But in reality, it had as much to do with society at large. As he acknowledged, the prohibitionists were putting him out of business. What he did not recognize was the self-inflicted wound administered by the brewing community on itself. Had the brewers been more united, less defensive, and more willing to reach out to other anti-prohibitionists in society, they might well have had beer—which was once considered a temperance drink—exempted from prohibitionist legislation.

From a nineteenth-century perspective, this was a very un-Canadian tale. Usually, business successfully lobbied government for the public policies it wanted. But in the case of the beer wars, the brewing industry ultimately failed to persuade the government to do its bidding.

From another perspective, however, the story was very Canadian. In the years following Confederation, the fragile Canadian nation was divided along regional, religious, and socio-economic lines. These divisions were omnipresent during the beer wars, dividing those within the brewing industry. Men like Konrad Knapp were trapped between their wallets and their social register. Steelmakers had no moral qualms about making steel because steel made nations. But did beer make nations? Or did it cause national decay? Knapp and most other Canadian brewers were increasingly uncertain. As a result, they served up a watered-down response to the threat of prohibition.

Prohibition primer

Sober second thought

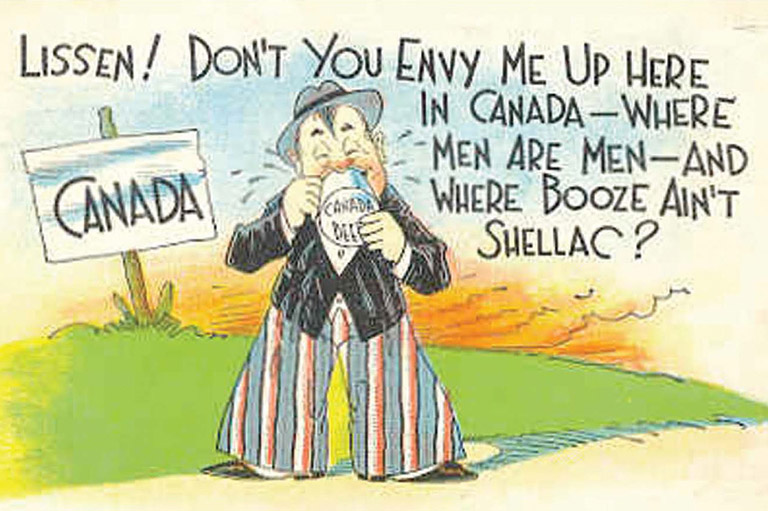

Unlike the United States, which imposed a nationwide prohibition on alcohol from 1920 to 1933, Canada never had a country-wide ban. There was an attempt to impose Canada-wide prohibition when, in 1898, a small majority of Canadians voted in a plebiscite to ban alcohol. However, Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier refused to impose such a law, saying a 51.3 percent majority was too small. Besides, Quebecers overwhelmingly opposed it.

Teetotalling by province

The decision was thus left to the provinces. Prince Edward Island was the first to get on the wagon; its prohibition period lasted the longest—from 1901 to 1948. Saskatchewan was next (1915 to 1925), then Ontario (1916 to 1927), Alberta (1916 to 1924), Manitoba (1916 to 1923), Nova Scotia (1916 to 1930), New Brunswick (1917 to 1927), and British Columbia (1917 to 1921). Newfoundland, which was not part of Canada at that time, imposed a prohibition law in 1917 and repealed it in 1924. Quebec’s experiment with banning alcohol in 1918 lasted only a few weeks.

Law and loophole

The laws generally closed drinking establishments and forbade the sale of alcohol. Exceptions were made for its use in such things as medicine and industry. Interestingly, distillers and brewers could still make their product and sell it outside the jurisdictions they were located in. This created a loophole that was exploited by a handful of industrious brewers. In March of 1918 the newly elected Unionist federal government of Robert Borden closed the loophole.

The hangover

Total prohibition proved unenforceable. It led to organized crime in the form of rum-running and a proliferation of illegal drinking establishments. However, the influence of the temperance movement lives on today in provincial liquor control boards, restrictions on advertising, and strict rules governing places where alcohol is served.

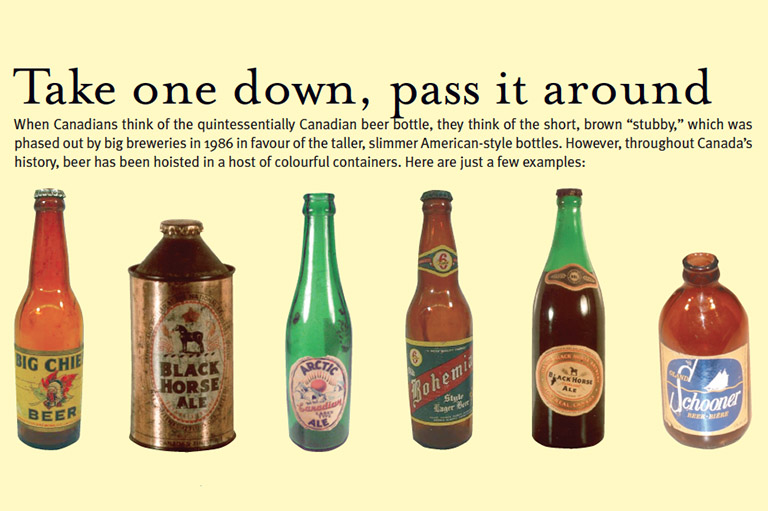

Canadians have enjoyed suds for centuries

Beer dates back as far as known civilization and has been a staple in cultures around the world. Made by combining water, a malted grain such as barley, a flavouring spice or herb such as hops, and yeast for fermentation, it was a relatively safe beverage in places where the water supply was unreliable. Beer also served as a nutritional component of diets, and has long played a role in religious and cultural events and ceremonies.

When Jacques Cartier arrived in North America, he and his crew were shown how to make the spruce beer Canada’s First Nations were already brewing. Many early settlers brewed beer in their homes, including, reportedly, Canada’s first farmer, Louis Hébert. Missionaries such as the Jesuits and Récollets set up breweries in New France early in the seventeenth century. But the foamy beverage was first produced on a large scale when Jean Talon, the colony’s intendant, established La Brasserie du Roy (the King’s Brewery) at Quebec City in 1668.

Talon hoped to solve a shortage of safe drinking water while making use of a grain surplus and competing with imported liquors to keep money in the colony. His brewery even produced beer for export, but lasted only a few years. Others that followed were similarly short-lived and brewing remained mostly a cottage industry over the next century.

The eighteenth-century arrival of British soldiers, who were entitled to six pints of beer a day, changed brewing in Canada. Small breweries and brew pubs thrived wherever there was a military post, while United Empire Loyalists brought English traditions to Upper Canada and the Maritimes. The Canadian taste for ales and other heavier beers, as opposed to the German-derived lagers popular in the U.S., can be traced to this time.

Brewing and malting were cool-weather activities farmers could engage in during the off-season, and at one point in the nineteenth century there were over three hundred small breweries in Ontario alone. English-born John Molson established the oldest among surviving Canadian brewing enterprises in Montreal in 1786.

— Phil Koch

High spirits

Canadians have long been consumed by alcohol.

Foxy wine: In 1811 a retired German soldier, Johann Schiller, became the “father of Canadian wine” when he planted a small vineyard just west of York (Toronto). However, the only grape varieties available at the time for this climate had a “foxy” taste that was only tolerable in port- and sherry-style wines.

Beer with buzz: Before prohibition, there was no such thing as “lite” beer. Its alcohol content ranged from eight to twelve percent, yet it was considered a “temperance drink.” A standard Canadian beer today is five percent.

Rum in the trenches: During the Great War, Canadian infantrymen were issued two ounces at dawn and two ounces at dusk. There was extra rum for those who went beyond the call of duty. A Private G. Boyd, who was at Passchendaele in 1917, said, “if we had not had the rum we would have died.”

Party-pooper: Edwin Clarke Appleby ran in the 1930 federal election in Canada as a Prohibition Party candidate in Vancouver-Burrard. A watchman by trade, Appleby came in dead last with 266 votes (0.8 percent of the popular vote).

Party animal: Carl Borden Campbell ran in 1979 Prince Edward Island election as a Draft Beer Party candidate, receiving 200 votes in a province that had not brewed its own beer since prohibition. There is now one small brewery on the island.

Et Cetera

The Molson Saga, 1763-1983: The Triumphs and Tragedies of the Legendary Brewing Family Through Six Generations by Shirley E. Woods, Jr. Avon Books of Canada, Scarborough, Ontario, 1983.

House of Suds: A History of Beer Brewing in Western Canada by William A. Hagelund. Hancock House Publishers, Surrey, B.C., 2003.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Save as much as 40% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital. Tariff-exempt!