True or False

The 150th anniversary of Confederation this July 1 is an absolutely remarkable achievement. The Confederation of 1867 was the bedrock of modern Canada, as it gave us both the union of the colonies and federalism as a system of governance.

The expansion of Canada from sea to sea made it the second-largest political entity in the world, and future generations inherited a wealth of geographic diversity and beauty, unique regions and peoples, and vast natural resources.

This enormous achievement has been celebrated from day one, but along the way some great myths have also arisen. Here’s a handy guide to sorting fact from fiction when it comes to Confederation.

1. Canada’s true age

It is often said that Canada was founded in 1867 and that we are celebrating its 150th anniversary this year. Actually, “Canada” was officially established on December 26, 1791, when a constitutional act came into effect that divided Quebec into Lower Canada and Upper Canada. Thus, the original Canada turns 226 years old this year. When the United Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia joined together in 1867, they took the name of the largest colony, “Canada,” and called it a Dominion to avoid confusing it with the old Province of Canada. So it’s only the Dominion that is 150 years old, Canada being much older and the confusion over its name much more recent.

2. A country and a nation, eh?

A favourite myth is that Canada became a country and a nation on July 1, 1867. However, a country is an area of land whose sovereignty or independence is recognized by other countries; Canada only became one when Britain finally recognized its independence in 1931. A nation is a group of people with a sense of identity based on things like common history, culture, values, language, and religion. In 1867, French Canadians, Acadians, and dozens of First Nations met that definition, as did the Irish, English, and Scots. By the mid-twentieth century the three latter groups had homogenized sufficiently to be called Canadians; but Quebecers did not see themselves as part of the same nation, and the First Nations and Inuit were still on the outside looking in.

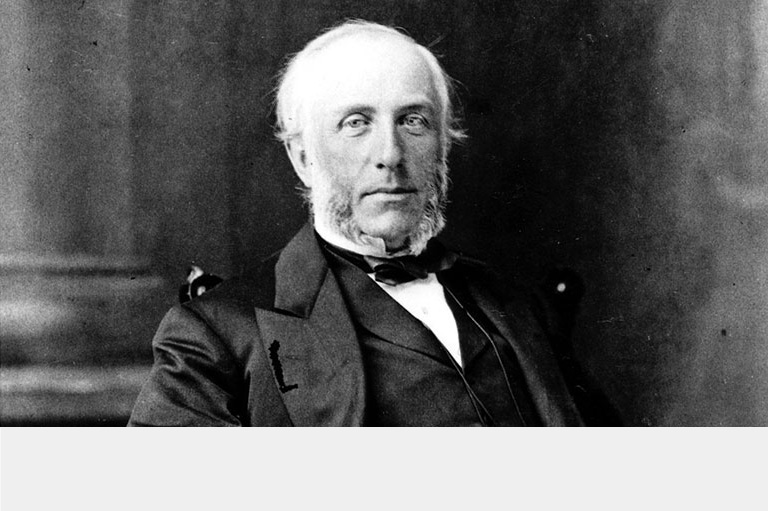

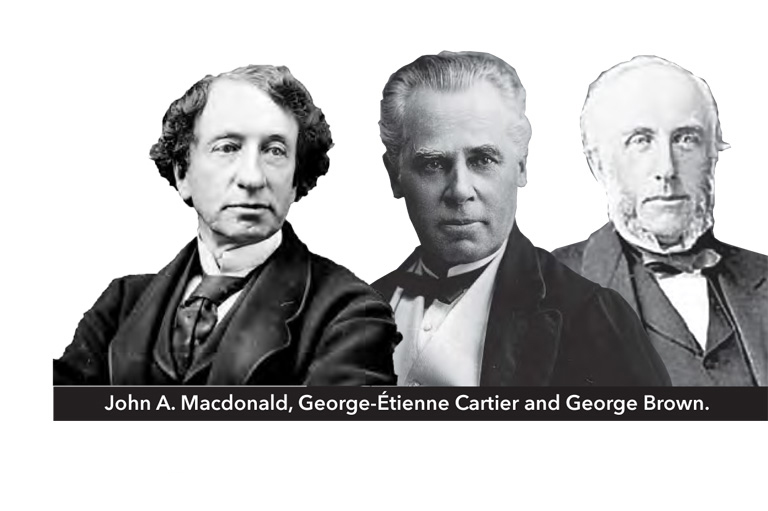

3. The divine Sir John A.

Since United States President George Washington could walk on water — according to American mythology — so Sir John A. Macdonald had to be elevated to near godlike status in Canada. He was perhaps the greatest and most important of our prime ministers, but he was only one of the three main architects of Confederation. George Brown and George-Étienne Cartier led the largest parties, and it was their agreement that led to federalism, something Macdonald unsuccessfully opposed throughout his career. He favoured a unitary system, where power is held by the central government. Macdonald’s outstanding contribution came later, when he made Confederation work, expanded it to the Pacific, and added the three provinces of Manitoba, B.C., and P.E.I.

4. Quebec: a province like the others?

Really? After the Second World War, it became popular to say that, while Quebec was culturally distinct, it was the same as the other provinces politically and constitutionally. In fact, the British North America Act identifies a number of ways in which Quebec is treated differently. Civil law, health, welfare, and education were made provincial responsibilities so Quebec could handle those matters independently — which it has proudly and defiantly done for a hundred and fifty years. These measures gave Quebec control over its language and culture. And there are other differences, like having a National Assembly.

5. Ottawa rules?

Perhaps the most important myth is that the central government was given, and still has, the most important jobs and is therefore superior to the provinces. The tasks it faced were certainly huge, but most things that affected a person’s individual life were provincial, as were some major economic responsibilities such as natural resources. Perhaps the true measure of relative importance is the fact that, since the First World War, the federal government has relentlessly attempted to gain influence over provincial responsibilities. The resulting struggle for power will likely continue for another century and a half as the saga of Confederation unfolds.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History Society today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

We are a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement